ploeh blog danish software design

Simplifying assertions with lenses

Get ready for some cryptic infix operators.

In a previous article I left you with a remaining problem: A test with an assertion weaker than warranted. In this article, you'll see a few tests like that, and how using lenses may improve the situation.

Weak tests #

The previous article already showed an example of a test I wasn't fully happy with. For convenience, I'll repeat it here.

testCase "Groom two finches" $ let cell1 = Galapagos.CellState (Just samaritan) (mkStdGen 0) cell2 = Galapagos.CellState (Just cheater) (mkStdGen 1) actual = Galapagos.groom Galapagos.defaultParams (cell1, cell2) expected = Just <$> Pair ( finchEq $ samaritan { Galapagos.finchHP = 16 } , finchEq $ cheater { Galapagos.finchHP = 13 } ) in (cellFinchEq <$> Pair actual) @?= expected

Another test exhibits the same problem, but since it's simpler, we'll start with that.

testCase "Age finch" $ let cell = Galapagos.CellState (Just samaritan) (mkStdGen 0) actual = Galapagos.age cell expected = finchEq $ samaritan { Galapagos.finchRoundsLeft = 3 } in cellFinchEq actual @?= Just expected

As you read on, you'll see what makes those tests awkward, but in short, they only compare the Finch part of a cell, rather than comparing entire cells. The reason is that full comparisons make the tests more complicated, and less readable.

Replacing Pair with both #

The problem is one that I rarely run into, because, as I outlined in the previous article (and many times before), if a test is difficult to write, I usually consider a simpler design. Because of Haskell's awkward copy-and-update syntax, I tend to avoid nested record types. (This also applies to F#.) Even so, it helps to know that when you run into nested records, lenses may be a proper response.

Since I prefer to avoid nested data types, I don't use lenses much, but when I have to, I tend to use the lens package, only because I'm of the impression that it's comprehensive and current.

Even so, I only rarely use it, so whenever I decide to pull it in, I need to get reacquainted with it. While I was spelunking the documentation, I came across the both function, and realized that it solves essentially the same problem as Pair from the previous article. So, to get an easy start, I decided to replace Pair with both, before proceeding with my actual pursuit.

The "Groom two finches" test then looked like this:

testCase "Groom two finches" $ let cell1 = Galapagos.CellState (Just samaritan) (mkStdGen 0) cell2 = Galapagos.CellState (Just cheater) (mkStdGen 1) actual = Galapagos.groom Galapagos.defaultParams (cell1, cell2) expected = ( Just $ finchEq $ samaritan { Galapagos.finchHP = 16 } , Just $ finchEq $ cheater { Galapagos.finchHP = 13 } ) in (actual & both %~ cellFinchEq) @?= expected

Notice that actual & both %~ cellFinchEq replaces cellFinchEq <$> Pair actual. In isolation, this is hardly more readable, but on the other hand, I believe that people often mistake unfamiliarity with things being hard to understand. If I imagine that all developers working with this code base are familiar with the lens library, actual & both %~ cellFinchEq may be perfectly legible.

Strengthening assertions the hard way #

Consider the "Age finch" test. The samaritan Finch value has finchRoundsLeft = 4. After each round of the cellular automaton, the age function decreases the value by one.

If I wanted to make that explicit, and also compare the actual CellState to the expected CellState, I could do it with standard Haskell language features, but the test starts to become awkward.

testCase "Age finch" $ let cell = Galapagos.CellState (Just samaritan) (mkStdGen 0) actual = Galapagos.age cell expected = cellStateEq $ cell { Galapagos.cellFinch = (\f -> f { Galapagos.finchRoundsLeft = Galapagos.finchRoundsLeft f - 1 }) <$> Galapagos.cellFinch cell } in cellStateEq actual @?= expected

This is clunky for a number of reasons: The Galapagos.cellFinch field returns the finch found in that cell, but since the cell may also be empty, the return value is a Maybe Finch. This means that any modification must be done with a projection; either fmap or, as shown here, <$>. Inside the lambda expression, I need to query Galapagos.finchRoundsLeft to get the current value, and then use copy-and-update syntax to bind the new value to Galapagos.finchRoundsLeft. And then this entire expression must be bound to Galapagos.cellFinch in order to update cell.

To summarize, both Galapagos.finchRoundsLeft and Galapagos.cellFinch has to appear twice.

The other test, "Groom two finches", involves two cells, so that's just double the cumber.

testCase "Groom two finches" $ let cell1 = Galapagos.CellState (Just samaritan) (mkStdGen 0) cell2 = Galapagos.CellState (Just cheater) (mkStdGen 1) actual = Galapagos.groom Galapagos.defaultParams (cell1, cell2) expected = ( cell1 { Galapagos.cellFinch = (\f -> f { Galapagos.finchHP = 16 }) <$> Galapagos.cellFinch cell1 } , cell2 { Galapagos.cellFinch = (\f -> f { Galapagos.finchHP = 13 }) <$> Galapagos.cellFinch cell2 } ) in (actual & both %~ cellStateEq) @?= (expected & both %~ cellStateEq)

This demonstrates why I originally took a shortcut. Even without trying it out in practice, I have enough experience with Haskell (and F#) to predict exactly this situation. Fortunately, there's a way out.

Setting an inner value #

Not being well-versed in the lens library, I found it prudent to proceed in small steps. My next move was to update finchRoundsLeft in the above "Age finch" test. While I quickly found the -~ operator, I then had to figure out how to define an ASetter for finchRoundsLeft.

All documentation points to making use of makeLenses, but that comes with requirements that I couldn't fulfil. I couldn't change the existing definition of Finch, so I couldn't name the fields according to the required naming convention. I tried to use makeLensesWith from another module, but I couldn't make it work. It's possible that you can make it work if you know what you are doing, but I didn't.

In the end, I just wrote an explicit setter function for finchRoundsLeft:

setRoundsLeft :: Functor f => (Galapagos.Rounds -> f Galapagos.Rounds) -> Galapagos.Finch -> f Galapagos.Finch setRoundsLeft f x = (\r -> x { Galapagos.finchRoundsLeft = r }) <$> f (Galapagos.finchRoundsLeft x)

This enabled me to rewrite the "Age finch" test to this:

testCase "Age finch" $ let cell = Galapagos.CellState (Just samaritan) (mkStdGen 0) actual = Galapagos.age cell expected = cellStateEq $ cell { Galapagos.cellFinch = (setRoundsLeft -~ 1) <$> Galapagos.cellFinch cell } in cellStateEq actual @?= expected

Granted, it's not much of an improvement, but it gave me an idea of how to proceed.

Composing setters #

Not only did I need a setter for finchRoundsLeft, I also needed one for cellFinch. Again, not being able to identify a way to do this in an easier way, I wrote another explicit setter for that purpose:

setFinch :: Functor f => (Maybe Galapagos.Finch -> f (Maybe Galapagos.Finch)) -> Galapagos.CellState -> f Galapagos.CellState setFinch f x = (\finch -> x { Galapagos.cellFinch = finch }) <$> f (Galapagos.cellFinch x)

Armed with that I could finally rewrite "Age finch" to something nice.

testCase "Age finch" $ let cell = Galapagos.CellState (Just samaritan) (mkStdGen 0) actual = Galapagos.age cell expected = cellStateEq $ cell & setFinch . _Just . setRoundsLeft -~ 1 in cellStateEq actual @?= expected

Likewise, with the addition of setHP, I could also rewrite "Groom two finches":

testCase "Groom two finches" $ let cell1 = Galapagos.CellState (Just samaritan) (mkStdGen 0) cell2 = Galapagos.CellState (Just cheater) (mkStdGen 1) actual = Galapagos.groom Galapagos.defaultParams (cell1, cell2) expected = ( cell1 & setFinch . _Just . setHP .~ 16 , cell2 & setFinch . _Just . setHP .~ 13 ) in (actual & both %~ cellStateEq) @?= (expected & both %~ cellStateEq)

That's not too bad, if I may say so.

Combinator golf #

Sometimes I get carried away. It's really nothing to worry about, but only to play with options in order to learn, I decided to address the duplication in the above assertion. Notice that is goes & both %~ cellStateEq twice. That's not something that should bother me, and in any case, if you apply the rule of three, it's too early to refactor.

Even so, I wanted that little bit of extra exercise, so I pulled in on and rewrote the assertion. All the other code is identical to the previous listing.

testCase "Groom two finches" $ let cell1 = Galapagos.CellState (Just samaritan) (mkStdGen 0) cell2 = Galapagos.CellState (Just cheater) (mkStdGen 1) actual = Galapagos.groom Galapagos.defaultParams (cell1, cell2) expected = ( cell1 & setFinch . _Just . setHP .~ 16 , cell2 & setFinch . _Just . setHP .~ 13 ) in ((@?=) `on` (both %~ cellStateEq)) actual expected

To be clear, I do, myself, consider this last edit frivolous. I wouldn't recommend it, and wouldn't use it in a code base shared with other people, but I still find it enjoyable.

Conclusion #

Nested data structures present problems in functional programming, particularly in Haskell, where the record syntax leaves something to be desired. Updating a value nested inside another value is, with plain vanilla code, awkward.

This kind of situation is the main use case for lenses. In this article, you saw how I refactored awkward tests with the lens package.

Code that fits in a context window

AI-friendly code?

On what's left of software-development social media, I see people complaining that as the size of a software system grows, large language models (LLMs) have an increasingly hard time advancing the system without breaking something else. Some people speculate that the context windows size limit may have something to do with this.

As a code base grows, an LLM may be unable to fit all of it, as well as the surrounding discussion, into the context window. Or so I gather from what I read.

This doesn't seem too different from limitations of the human brain. To be more precise, a brain is not a computer, and while they share similarities, there are also significant differences.

Even so, a major hypothesis of mine is that what makes programming difficult for humans is that our short-term memory is shockingly limited. Based on that notion, a few years ago I wrote a book called Code That Fits in Your Head.

In the book, I describe a broad set of heuristics and practices for working with code, based on the hypothesis that working memory is limited. One of the most important ideas is the notion of Fractal Architecture. Regardless of the abstraction level, the code is composed of only a few parts. As you look at one part, however, you find that it's made from a few smaller parts, and so on.

I wonder if those notions wouldn't be useful for LLMs, too.

AI-generated tests as ceremony

On epistemological soundness of using LLMs to generate automated tests.

For decades, software development thought leaders have tried to convince the industry that test-driven development (TDD) should be the norm. I think so too. Even so, the majority of developers don't use TDD. If they write tests, they add them after having written production code.

With the rise of large language models (LLMs, so-called AI) many developers see new opportunities: Let LLMs write the tests.

Is this a good idea?

After having thought about this for some time, I've come to the interim conclusion that it seems to be missing the point. It's tests as ceremony, rather than tests as an application of the scientific method.

How do you know that LLM-generated code works? #

People who are enthusiastic about using LLMs for programming often emphasise the the amount of code they can produce. It's striking so quickly the industry forgets that lines of code isn't a measure of productivity. We already had trouble with the amount of code that existed back when humans wrote it. Why do we think that accelerating this process is going to be an improvement?

When people wax lyrical about all the code that LLMs generated, I usually ask: How do you know that it works? To which the most common answer seems to be: I looked at the code, and it's fine.

This is where the discussion becomes difficult, because it's hard to respond to this claim without risking offending people. For what it's worth, I've personally looked at much code and deemed it correct, only to later discover that it contained defects. How do people think that bugs make it past code review and into production?

It's as if some variant of Gell-Mann amnesia is at work. Whenever a bug makes it into production, you acknowledge that it 'slipped past' vigilant efforts of quality assurance, but as soon as you've fixed the problem, you go back to believing that code-reading can prevent defects.

To be clear, I'm a big proponent of code reviews. To the degree that any science is done in this field, research indicates that it's one of the better ways of catching bugs early. My own experience supports this to a degree, but an effective code review is a concentrated effort. It's not a cursory scan over dozens of code files, followed by LGTM.

The world isn't black or white. There are stories of LLMs producing near-ready forms-over-data applications. Granted, this type of code is often repetitive, but uncomplicated. It's conceivable that if the code looks reasonable and smoke tests indicate that the application works, it most likely does. Furthermore, not all software is born equal. In some systems, errors are catastrophic, whereas in others, they're merely inconveniences.

There's little doubt that LLM-generated software is part of our future. This, in itself, may or may not be fine. We still need, however, to figure out how that impacts development processes. What does it mean, for example, related to software testing?

Using LLMs to generate tests #

Since automated tests, such as unit tests, are written in a programming language, the practice of automated testing has always been burdened with the obvious question: If we write code to test code, how do we know that the test code works? Who watches the watchmen? Is it going to be turtles all the way down?

The answer, as argued in Epistemology of software, is that seeing a test fail is an example of the scientific method. It corroborates the (often unstated, implied) hypothesis that a new test, of a feature not yet implemented, should fail, thereby demonstrating the need for adding code to the System Under Test (SUT). This doesn't prove that the test is correct, but increases our rational belief that it is.

When using LLMs to generate tests for existing code, you skip this step. How do you know, then, that the generated test code is correct? That all tests pass is hardly a useful criterion. Looking at the test code may catch obvious errors, but again: Those people who already view automated tests as a chore to be done with aren't likely to perform a thorough code reading. And even a proper review may fail to unearth problems, such as tautological assertions.

Rather, using LLMs to generate tests may lull you into a false sense of security. After all, now you have tests.

What is missing from this process is an understanding of why tests work in the first place. Tests work best when you have seen them fail.

Toward epistemological soundness #

Is there a way to take advantage of LLMs when writing tests? This is clearly a field where we have yet to discover better practices. Until then, here are a few ideas.

When writing tests after production code, you can still apply empirical Characterization Testing. In this process, you deliberately temporarily sabotage the SUT to see a test fail, and then revert that change. When using LLM-generated tests, you can still do this.

Obviously, this requires more work, and takes more time, than 'just' asking an LLM to generate tests, run them, and check them in, but it would put you on epistemologically safer ground.

Another option is to ask LLMs to follow TDD. On what's left of technical social media, I see occasional noises indicating that people are doing this. Again, however, I think the devil is in the details. What is the actual process when asking an LLM to follow TDD?

Do you ask the LLM to write a test, then review the test, run it, and see it fail? Then stage the code changes? Then ask the LLM to pass the test? Then verify that the LLM did not change the test while passing it? Review the additional code change? Commit and repeat? If so, this sounds epistemologically sound.

If, on the other hand, you let it go in a fast loop where the only observations your human brain can keep up with is that test status oscillates between red and green, then you're back to where we started: This is essentially ex-post tests with extra ceremony.

Cargo-cult testing #

These days, most programmers have heard about cargo-cult programming, where coders perform ceremonies hoping for favourable outcomes, confusing cause and effect.

Having LLMs write unit tests strikes me as a process with little epistemological content. Imagine, for the sake of argument, that the LLM never produces code in a high-level programming language. Instead, it goes straight to machine code. Assuming that you don't read machine code, how much would you trust the generated system? Would you trust it more if you asked the LLM to write tests? What does a test program even indicate? You may be given a program that ostensibly tests the system, but how do you know that it isn't a simulation? A program that only looks as though it runs tests, but is, in fact, unrelated to the actual system?

You may find that a contrived thought experiment, but this is effectively the definition of vibe coding. You don't inspect the generated code, so the language becomes functionally irrelevant.

Without human engagement, tests strike me as mere ceremony.

Ways forward #

It would be naive of me to believe that programmers stop using LLMs to generate code, including unit tests. Are there techniques we can apply to put software development back on more solid footing?

As always when new technology enters the picture, we've yet to discover efficient practices. Meanwhile, we may attempt to apply the knowledge and experience we have from the old ways of doing things.

I've already outlined a few technique to keep you on good epistemological footing, but I surmise that people who already find writing tests a chore aren't going to take the time to systematically apply the techniques for empirical Characterization Testing.

Another option is to turn the tables. Instead of writing production code and asking LLMs to write tests, why not write tests, and ask LLMs to implement the SUT? This would entail a mostly black-box approach to TDD, but still seems scientific to me.

For some reason I've never understood, however, most people dislike writing tests, so this is probably unrealistic, too. As a supplement, then, we should explore ways to critique tests.

Conclusion #

It may seem alluring to let LLMs relieve you of the burden it is to write automated tests. If, however, you don't engage with the tests it generates, you can't tell what guarantees they give. If so, what benefits do the tests provide? Do automated testing become mere ceremony, intended to give you a nice warm feeling with little real protection?

I think that there are ways around this problem, some of which are already in view, but some of which we have probably yet to discover.

Filtering as domain logic

Performance and correctness are two independent concerns with overlapping solutions.

How do you design, implement, maintain, and test complex filter logic as part of out-of-process (e.g. database) queries?

One option is to implement parts of the filtering logic twice: Once as an easily-testable in-memory implementation to ensure correctness, and another, possibly simpler, query using the query language (usually, SQL) of the data source.

Does this not imply duplication of effort? Yes, to a degree it does. Should you always do this? No, only when warranted. As usual, I present this idea as an option you may consider; a tool for your software design tool belt. You decide if it's useful in your particular context.

Motivation #

When extracting data from a data source, an application usually needs some of the data, but not all of it. If the software system in question has a certain size, the subset required for an operation is only a miniscule fraction of the entire database. For example, a user may want to see his or her latest order in a web shop, but the entire system contains millions of orders. Another example could be a system for managing help desk requests: Each supporter may need a dashboard of open cases assigned to him or her, but the system holds millions of tickets, and most of them are closed.

If a data store supports server-side querying, for example with SQL or Cypher, it's reasonable to let the data store itself do the filtering.

As anyone who has worked professionally with SQL can attest, SQL queries can become complicated. When this happens, you may become concerned with the correctness of a query. Does it include all the data it should? Does it exclude irrelevant data? If you later change a query, how can you verify that it still works as intended? How do you even version it?

Automated testing can address several of these concerns, but testing against a real database, while possible, tends to be cumbersome and slow. Do alternatives, or augmentations, exist?

How it works #

If a server-side query threatens to become too complicated, consider shifting some of the work to clients. You may retain some filtering logic in the server-side query, but only enough to keep performance good, and simple enough that you are no longer concerned about its correctness.

Implement the difficult filtering logic in a client-side library. Since you implement this part in a programming language of your choice, you can use any tool or technique available in that context to ensure correctness: Test-driven development, static code analysis, type checking, property-based testing, code coverage, mutation testing, etc.

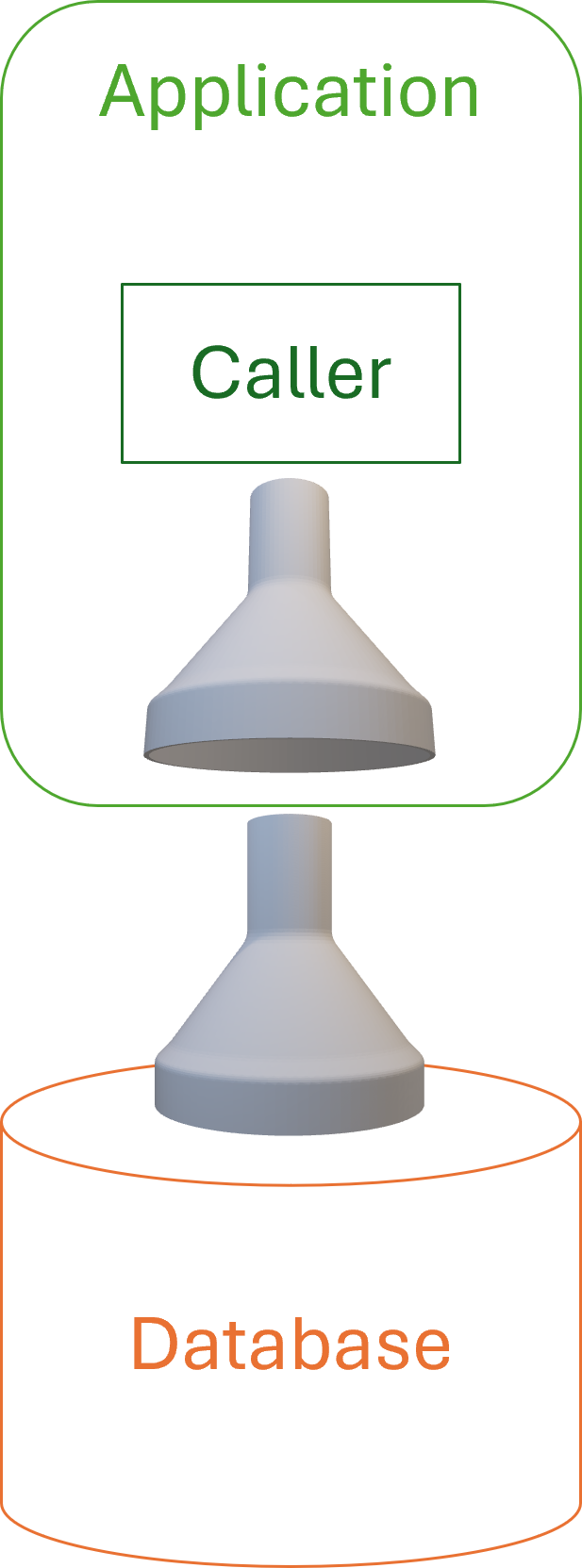

Using a funnel as a symbol of filtering, this diagram depicts the idea:

Normally a funnel is only useful when the widest part faces up, but on the other hand, we usually depict application architectures with the database under the the application. You have to imagine data being 'sucked up' through the funnels.

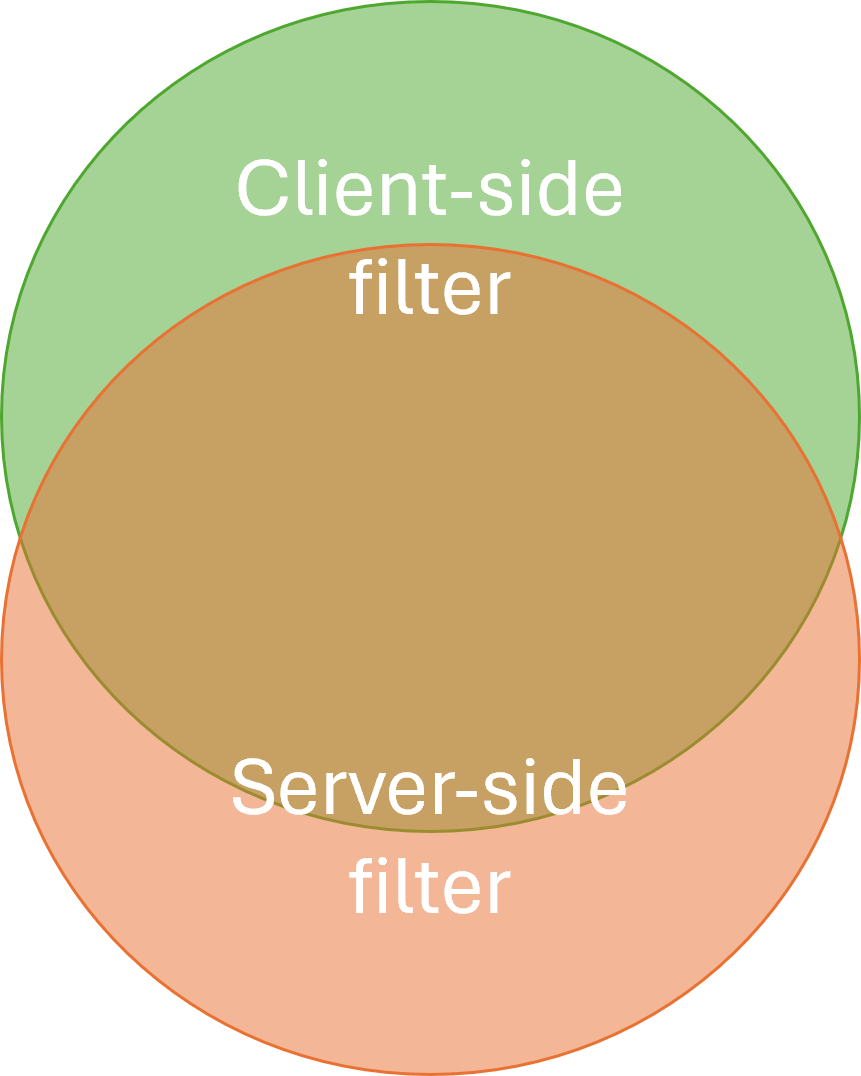

In reality, the two filters will differ, but have overlapping functionality.

If based on a relational database, the server-side query will still hold table joins and column projections that are effectively irrelevant to the client-side Domain Model. On the other hand, while the server-side query may apply a rough filter, the more detailed selection of what is, and is not, included happens in the client.

The server-side query is defined using the query language of the data store, such as SQL or Cypher. The client-side query is part of the application code base, and written in the same programming language.

When to use it #

Use this pattern if a server-side query becomes so complicated that you are concerned about its correctness, or if correctness is an essential part of a Domain Model's contract.

While it is conceptually possible to load the entire data store's data into memory, this is often prohibitively expensive in terms of time and memory. It is often necessary to retain some filtering logic (e.g. one or more SQL WHERE clauses) on the server to pare down data to acceptable sizes. This implies a degree of duplicated logic, since the client-side filter shouldn't assume that any filtering has been applied.

Duplication comes with its own set of problems, even if this looks like the benign kind. Alternatives include keeping all logic on the database server, which is viable if the logic is simple, or can be sufficiently simplified. Another alternative is to perform all filtering in the client, which may be an attractive solution if the entire data set is small.

Encapsulation #

If a Domain Model is composed of pure functions, data must be supplied as normal input arguments. In a more object-oriented style, data may arrive as indirect input. In both object-oriented and functional architecture, encapsulation is important. This entails being explicit about invariants and pre- and postconditions; i.e. contracts.

To enforce preconditions, a Domain Model must ensure that input is correct. While it could choose to reject input if it contains 'too much' data, a Tolerant Reader should instead pare the data down to size. This implies that filtering should be part of a Domain Model's contract.

This further implies that a Domain Model becomes less vulnerable to changes in data access code.

Implementation details #

Server-side filtering (with e.g. SQL) is often difficult to test with sufficient rigour. The point of moving the complex filtering logic to the Domain Model is that this makes it easier to test, and thereby to maintain.

If no filtering takes place on the server, however, the entire data set of the system would have to be transmitted to, and filtered on, the client. This is usually too expensive, so some filtering must still take place at the data source. The whole point of this exercise is that the 'correct' filtering is too complicated to maintain as a server-side query, so whatever filtering still takes place on the server only happens for performance reasons, and can be simpler, as long as it's wider.

Specifically, the simplified server-side query can (and probably should) be wider, in the sense that it returns more data than is required for the correctness of the overall system. The client, receiving more data than strictly required, can perform more sophisticated (and testable) filtering.

The simplified filtering on the server must not, on the other hand, narrow the result set. If relevant data is left out at the source, the client has no chance to restore it, or even know that it exists.

Motivating example #

The code base that accompanies Code That Fits in Your Head contains an example. When a user attempts to make a restaurant reservation, the system must look at existing reservations on the same date to check whether it has a free table. Many restaurants operate with seating windows, and the logic involved in figuring out if a time slot is free is easy to get wrong. On top of that, the decision logic needs to take opening hours and last seating into account. The book, as well as the article The Maître d' kata, has more details.

Based on information about seating duration, opening hours, and so on, it seems as though it should be possible to form an exact SQL query that only returns existing reservations that overlap the new reservation. Even so, this struck me as error-prone. Instead, I decided to make input filtering part of the Domain Model.

The Domain Model in question, an immutable class named MaitreD, uses the WillAccept method to decide whether to accept a reservation request. Apart from the candidate reservation, it also takes as parameters existingReservations as well as the current time.

public bool WillAccept( DateTime now, IEnumerable<Reservation> existingReservations, Reservation candidate)

The function uses the existingReservations to filter so that only the relevant reservations are considered:

var seating = new Seating(SeatingDuration, candidate.At); var relevantReservations = existingReservations.Where(seating.Overlaps);

As implied by this code snippet, a specialized Domain Model named Seating contains the actual filtering logic:

public bool Overlaps(Reservation otherReservation) { if (otherReservation is null) throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(otherReservation)); var other = new Seating(SeatingDuration, otherReservation.At); return Overlaps(other); } public bool Overlaps(Seating other) { if (other is null) throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(other)); return Start < other.End && other.Start < End; }

Notice how the core implementation, the overload that takes another Seating object, implements a binary relation. To extrapolate from Domain-Driven Design, whenever you arrive at 'proper' mathematics to describe the application domain, it's usually a sign that you've arrived at something fundamental.

The Overlaps functions are public and easy to unit test in their own right. Even so, in the code base that accompanies Code That Fits in Your Head, there are no tests that directly exercise these functions, since they only grew out of refactoring the implementation of MaitreD.WillAccept, which is covered by many tests. Since the Overlaps functions only emerged as a result of test-driven development, they might as well have been private helper methods, but I later needed them for verifying some unrelated test outcomes.

The filtering performed in WillAccept will throw away any reservations that don't overlap. Even if existingReservations contained the entire data set from the database, it would still be correct. Given, however, that there could be hundreds of thousands of reservations, it seems prudent to perform some coarse-grained filtering in the database.

The ReservationsController that calls WillAccept first queries the database, getting all the reservation on the relevant date.

var reservations = await Repository .ReadReservations(restaurant.Id, reservation.At) .ConfigureAwait(false);

Now that I write this description, I realize this query, while wide in one sense, could actually be too narrow. None of my test restaurants have a last seating after midnight, but I wouldn't rule that out in certain cultures. If so, it's easy to widen the coarse-grained query to include reservations for the day before (for breakfast restaurants, perhaps) and the day after, assuming that no seating lasts more than 24 hours.

All that said, the point is that ReadReservations(restaurant.Id, reservation.At) (which is an extension method) performs a simple, coarse-grained query for reservations that may be relevant to consider, given the candidate reservation. This query should return a 'gross' data set that contains all relevant, but also some irrelevant, reservations, thereby keeping the query simple. An indeed, the actual database interaction is this parametrised query:

SELECT [PublicId], [At], [Name], [Email], [Quantity] FROM [dbo].[Reservations] WHERE [RestaurantId] = @RestaurantId AND @Min <= [At] AND [At] <= @Max

This range query should be simple enough that a few integration tests should be sufficient to give you confidence that it works correctly.

Consequences #

The main benefit from a design like this is that it shifts some of the burden of correctness to the Domain Model, which is easier to test, maintain, and version than is typically the case for query languages. An added advantage is improved separation of concerns.

In practice, server-side filtering tends to mix two independent concerns: Performance and correctness. Filtering is important for performance, because the alternative is to transmit all rows to the client. Filtering is also important for correctness, because the code making use of the data should only consider data relevant for its purpose. Exclusive server-side filtering performs both of these tasks, thereby mixing concerns. Moving filtering for correctness to a Domain Model can make explicit that these are two separate concerns.

While a Domain Model can implement in-memory filtering, it can only deal with data that is too wide; that is, it can identify and remove superfluous data. If, on the other hand, the dataset passed to the Domain Model lacks relevant records, the Domain Model can't detect that. The above discussion about the reservation system contains a concrete discussion of such a problem. Thus, Domain-based filtering does not alleviate developers from the burden of ensuring that any server-side filtering is sufficiently permissible.

Another consequence of this design is that as server-side queries become more coarse-grained, this could increase potential cache hit ratios. If you somehow cache queries, when queries become more general, there will be less variation, and thus caches will need fewer entries that will statistically be hit more often. This applies to CQRS-style architectures, too.

Consider the restaurant reservation example, above. Since queries are only distinguished by date, you can easily cache query results by date, and all reservation requests for a given date may go through that cache. If, as a counter-example, all filtering took place in the database, a query for a reservation at 18:00 would be different from a query for 18:30, and so on. This would make a hypothetical cache bigger, and decrease the frequency of cache hits.

Test evidence #

When I originally decided that WillAccept should perform in-memory filtering, my motivation was one of correctness. I was concerned whether I could get the seating overlap detection correct without comprehensive testing, and I thought that it would be easier to test a function doing in-memory filtering than to drive all of this via integration tests involving a real SQL Server instance. (Not that I don't know how to do this. The code base accompanying the book has examples of tests that exercise the database. These tests are, however, more work to write and maintain, and they execute slower.)

As discussed in Coupling from a big-O perspective, I much later realized that I actually had no test coverage of edge cases related to querying the database. It was only after attempting to write such a test that I realized that the design had the consequence that a marginal error in the database query had no impact on the correctness of the overall system. Here's that test:

[Fact] public async Task AttemptEdgeCaseBooking() { var twentyFour7 = new Restaurant( 247, "24/7", new MaitreD( opensAt: TimeSpan.FromHours(0), lastSeating: TimeSpan.FromHours(0), seatingDuration: TimeSpan.FromDays(1), tables: Table.Standard(1))); var db = new FakeDatabase(); var now = DateTime.Now; var sut = new ReservationsController( new SystemClock(), new InMemoryRestaurantDatabase(twentyFour7), db); var r1 = Some.Reservation.WithDate(now.AddDays(3).Date); await sut.Post(twentyFour7.Id, r1.ToDto()); var r2 = Some.Reservation.WithDate(now.AddDays(2).Date); var ar = await sut.Post(twentyFour7.Id, r2.ToDto()); Assert.IsAssignableFrom<CreatedAtActionResult>(ar); // More assertions could go here. }

This test is an attempt to cover the edge case related to how the system queries the database, just like the Moq-based test shown in Greyscale-box test-driven development. The idea is to create a reservation that just barely touches a reservation the following day, and thereby trigger a test failure when a change is made to the query, similar to how the Moq-based test fails. Even with a custom restaurant, I can't, however, get this test to fail, because of the Domain-based filtering, which keeps the system working correctly.

It was then that I realized that what I had inadvertently done was to strengthen the contract of WillAccept, compared to a more stereotypical design. Who knew test-driven development could lead to better encapsulation?

Conclusion #

Some queries may become so complicated that they are difficult to maintain. Bugs creep in, you address them, only to reanimate regressions. When this happens, consider moving the complicated parts of data filtering to the client, preferably to a Domain Model. This enables you to test the filtering logic with as much rigour as is required.

For small databases, you may read the entire dataset into memory, but usually you will need to retain some coarse-grained filtering on the database server.

This design, while more complicated than letting a query language like SQL handle all filtering, can lead to better encapsulation and separation of concerns.

Two regimes of Git

Using Git for CI is not the same as Tactical Git.

Git is such a versatile tool that when discussing it, interlocutors may often talk past each other. One person's use is so different from the way the next person uses it that every discussion is fraught with risk of misunderstandings. This happens to me a lot, because I use Git in two radically different ways, depending on context.

Should you rebase? Merge? Squash? Cherry-pick?

Often, being more explicit about a context can help address confusion.

I know of at least two ways of using Git that differ so much from each other that I think we may term them two different regimes. The rules I follow in one regime don't all apply in the other, and vice versa.

In this article I'll describe both regimes.

Collaboration #

Most people use Git because it facilitates collaboration. Like other source-control systems, it's a way to share a code base with coworkers, or open-source contributors. Continuous Integration is a subset in this category, and to my knowledge still the best way to collaborate.

When I work in this regime, I follow one dominant rule: Once history is shared with others, it should be considered immutable. When you push to a shared instance of the repository, other people may pull your changes. Changing the history after having shared it is going to confuse most Git clients. It's much easier to abstain from editing shared history.

What if you shared something that contains an error? Then fix the error and push that update, too. Sometimes, you can use git revert for this.

A special case is reserved for mistakes that involve leaking security-sensitive data. If you accidentally share a password, a revert doesn't rectify the problem. The data is still in the history, so this is a singular case where I know of no better remedy than rewriting history. That is, however, quite bothersome, because you now need to communicate to every other collaborator that this is going to happen, and that they may be best off making a new clone of the repository. If there's a better way to address such situations, I don't know of it, but would be happy to learn.

Another consequence of the Collaboration regime follows from the way pull requests are typically implemented. In GitHub, sending a pull request is a two-step process: First you push a branch, and then you click a button to send the pull request. I usually use the GitHub web user interface to review my own pull-request branch before pushing the button. Occasionally I spot an error. At this point I consider the branch 'unshared', so I may decide to rewrite the history of that branch and force-push it. Once, however, I've clicked the button and sent the pull request, I consider the branch shared, and the same rules apply: Rewriting history is not allowed.

One implication of this is that the set of Git actions you need to know is small: You can effectively get by with git add, commit, pull, push, and possibly a few more.

Many of the 'advanced' Git features, such as rebase and squash, allow you to rewrite history, so aren't allowed in this regime.

Tactical Git #

As far as I can tell, Git wasn't originally created for this second use case, but it turns out that it's incredibly useful for local management of code files. This is what I've previously described as Tactical Git.

Once you realize that you have a version-control system at your fingertips, the opportunities are manifold. You can perform experiments in a branch that only exists on your machine. You may, for example, test alternative API design ideas, implementations, etc. There's no reason to litter the code base with commented-out code because you're afraid that you'll need something later. Just commit it on a local branch. If it later turns out that the experiment didn't turn out to your liking, commit it anyway, but then check out master. You'll leave the experiment on your local machine, and it's there if you need it later.

You can even used failed experiments as evidence that a particular idea has undesirable consequences. Have you ever been in a situation where a coworker suggests a new way of doing things. You may have previously responded that you've already tried that, and it didn't work. How well did that answer go over with your coworker?

He or she probably wasn't convinced.

What if, however, you've kept that experiment on your own machine? Now you can say: "Not only have I already tried this, but I'm happy to share the relevant branch with you."

You can see an example of that in listing 8.10 in Code That Fits in Your Head. This code listing is based on a side-branch never merged into master. If you have the book, you also have access to the entire Git repository, and you can check for yourself that commit 0bb8068 is a dead-end branch named explode-maitre-d-arguments.

Under the Tactical Git regime, you can also go back and edit mistakes when working on code that you haven't yet shared. I use micro-commits, so I tend to check in small commits often. Sometimes, as I'm working with the code, I notice that I made a mistake a few commits ago. Since I'm a neat freak, I often use interactive rebase to go back and correct my mistakes before sharing the history with anyone else. I don't do that to look perfect, but rather to leave behind a legible trail of changes. If I already know that I made a mistake before I've shared my code with anyone else, there's no reason to burden others with both the mistake and its rectification.

In general, I aim to leave as nice a Git history as possible. This is not only for my collaborators' sake, but for my own, too. Legible Git histories and micro-commits make it easier to troubleshoot later, as this story demonstrates.

The toolset useful for Tactical Git is different than for collaboration. You still use add and commit, of course, but I also use (interactive) rebase often, as well as stash and branch. Only rarely do I need cherry-pick, but it's useful when I do need it.

Conclusion #

When discussing good Git practices, it's easy to misunderstand each other because there's more than one way to use Git. I know of at least two radically different modes: Collaboration and Tactical Git. The rules that apply under the Collaboration regime should not all be followed slavishly when in the Tactical Git regime. Specifically, the rule about rewriting history is almost turned on its head. Under the Collaboration regime, do not rewrite Git history; under the Tactical Git regime, rewriting history is encouraged.

Coupling from a big-O perspective

Don't repeat yourself (DRY) implies O(1) edits.

Here's a half-baked idea: We may view coupling in software through the lens of big-O notation. Since this isn't yet a fully-formed idea of mine, this is one of those articles I write in order to learn from the process of having to formulate the idea to other people.

Widening the scope of big-O analysis #

Big-O analysis is usually described in terms of functions on ℝ (the real numbers), such as O(n), O(lg n), O(n3), O(2n) and so on. This is somewhat ironic because when analysing algorithm efficiency, n is usually an integer (i.e. n ∈ ℕ). That, however, suits me fine, because it establishes precedence for what I have in mind.

Usually, big-O analysis is applied to algorithms, and usually by measuring an abstract notion of an 'instruction step'. You can, however, also apply such analysis to other aspects of resource utilization. Even within the confines of algorithm analysis, you may instead of instruction count be concerned with memory consumption. In other words, you may analyze an algorithm in order to determine that it uses O(n2) memory.

With that in mind, nothing prevents you from widening the scope further. While I tend to be disinterested in the small-scale performance optimizations involved with algorithms, I have a keen eye on how it applies to software architecture. In modern computers, CPU cycles are fast, but network hops are still noticeable to human perception. For example, the well-known n+1 problem really just implies O(n) network calls. Given that a single network hop may already (depending on topology and distance) be observable, even moderate numbers of n (e.g. 100) may be a problem.

What I have in mind for this article is to once more transplant the thinking behind big-O notation to a new area. Instead of instructions or network calls, let O(...) indicate the number of edits you have to make in a code base in order to make a change. If we want to be more practical about it, we may measure this number in how many methods or functions we need to edit, or, even more coarsely, the number of files we need to change.

Don't Repeat Yourself #

In this view, the old DRY principle implies O(1) edits. You create a single point in your code base responsible for a given behaviour. If you need to make changes, you edit a single part of the code base. This seems obvious.

What the big-O perspective implies, however, is that a small constant number of edits may be fine, too. For instance, 'dual' coupling, where two code blocks change together, is not that uncommon. This could for example be where you model messages on an internal queue. Every time you add a new message type, you'll need to define both how to send it (i.e. what data it contains and how it serializes) and how to handle it. If you are using a statically typed language, you can use a sum type or Visitor to keep track of all message types, which means that the type checker will remind you if you forget one or the other.

In big-O notation, we simplify all constants to 1, so even if you have systematic, but constant, coupling like this, we would still consider it O(1). In other words, if your architecture contains some coupling that remains constant, we may deem it O(1) and perhaps benign.

This also suggests why we have a heuristic like the rule of three. Dual duplication is still O(1), and as long as the coupling stays constant, there's no evidence that it's growing. Once you make the third copy does evidence begin to suggest that the coupling is O(n) rather than O(1).

Small values of 1 #

Big-O notation is concerned with comparing orders of magnitude, which is why specific constants are simplified to 1. The number 1 is a stand-in for any constant value, 1, 2, 10, og even six billion. When editing source code, however, the actual number of edits does matter. In the following sections, I'll give concrete examples where '1' is small.

Test-specific equality #

The first example we may consider is test-specific equality. My first treatment related to this topic was in 2010, and again in 2012. Since then, I've come to view the need for test-specific equality as a test smell. If you are doing test-driven development (which you chiefly should), giving your objects or values sane equality semantics makes testing much easier. And a well-known benefit of test-driven development (TDD) is that code that is easy to test is easy to use.

Still, if you must work with mutable objects (as in naive object-oriented design), you can't give objects structural equality. And as I recently rediscovered, functional programming doesn't entirely shield you from this kind of problem either. Functions, for example, don't have clear equality semantics in practice, so when bundling data and behaviour (does that sound familiar?), data structures can't have structural equality.

Still, TDD suggests that you should reconsider your API design when that happens. Sometimes, however, part of an API is locked. I recently described such a situation, which prompted me to write test-specific Eq instances. In short, the Haskell data type Finch was not an Eq instance, so I added this test-specific data type to improve testability:

data FinchEq = FinchEq { feqID :: Int , feqHP :: Galapagos.HP , feqRoundsLeft :: Galapagos.Rounds , feqColour :: Galapagos.Colour , feqStrategyExp :: Exp } deriving (Eq, Show)

Later, I also introduced a second test-specific data structure, CellStateEq to address the equivalent problem that CellState isn't an Eq instance. This means that I have two representations of essentially the same kind of data. If I, much later, learn that I need to add, remove, or modify a field of, say, Finch, I would also need to edit FinchEq.

There's a clear edit-time coupling with constant value 2. When I edit one, I also need to edit the other. In big-O perspective, we could say that the specific value of 1 is 2, or 1~2, and so the edits required to maintain this part of the code base is of the order O(1).

Maintaining Fake objects #

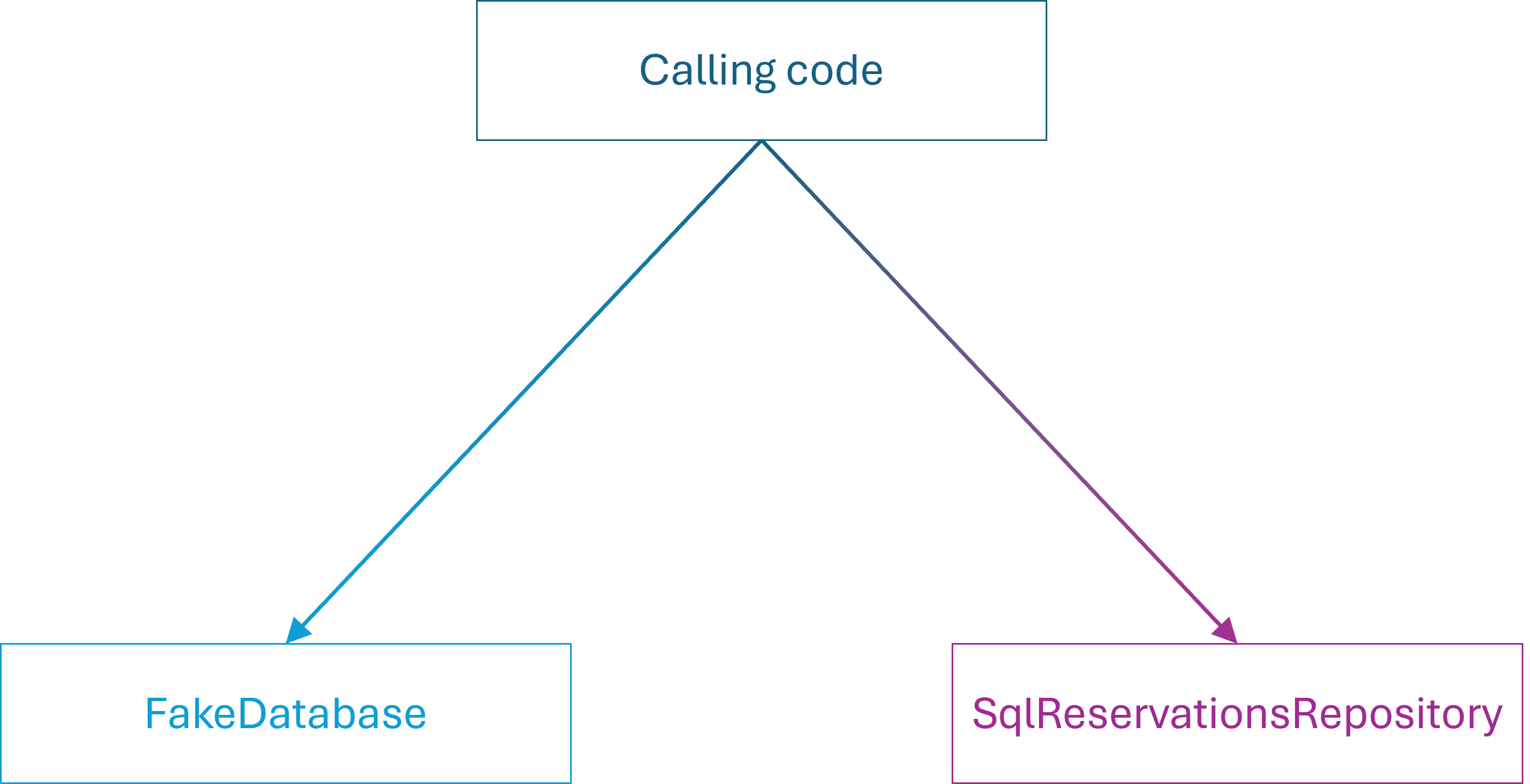

Another interesting example is the one that originally elicited this chain of thought. In Greyscale-box test-driven development I showed an example of how using interactive white-box testing with Dynamically Generated Test Doubles (AKA Dynamic Mocks) leads to Fragile Tests. More on this later, but I also described how using Fake Objects and state-based testing doesn't have the same problem.

In a response on Bluesky Laszlo (@ladeak.net) pointed out that this seemed to imply a three-way coupling that I had, frankly, overlooked.

You can review the full description of the example in the article Greyscale-box test-driven development, but in summary it proceeds like this: We wish to modify an implementation detail related to how the system queries its database. Specifically, we wish to change an inclusive integer-based upper bound to an exclusive bound. Thus, we change the relevant part of the SQL WHERE clause from

@Min <= [At] AND [At] <= @Max"

to

@Min <= [At] AND [At] < @Max"

Specifically, the single-character edit removes = from the rightmost <=.

Since this modification changes the implied contract, we also need to edit the calling code. That's another single-line edit that changes

var max = min.AddDays(1).AddTicks(-1);

to

var max = min.AddDays(1);

What I had overlooked was that I should also have changed the single test-specific Fake object used for state-based testing. Since I changed the contract of the IReservationsRepository interface, and since Fakes are Test Doubles with contracts, it follows that the FakeDatabase class must also change.

This I had overlooked because no tests based on FakeDatabase failed. More on that in a future post, but the required edit is easy enough. Change

.Where(r => min <= r.At && r.At <= max).ToList());

to

.Where(r => min <= r.At && r.At < max).ToList());

Again, the edit involves deleting a single = character.

Still, in this example, not only two, but three files are coupled. With the perspective of big-O notation, however, we may say that 1~3, and the order of edits required to maintain this part of the code base remains O(1). Later in this article, I will discuss the maintenance burden of dynamic mocks, which I consider to be O(n). Thus, even if I have a three-way coupling, I don't expect the coupling to grow over time. That's the point: I prefer O(1) over O(n).

Large values of 1 #

As I'm sure practical programmers know, big-O notation has limitations. First, as Rob Pike observed, "n is usually small". More germane to this discussion

"algorithms have big constants."

In this context, this implies that the constant we're deliberately ignoring when we label something O(1) could, in theory, be significant. We don't write O(2,000,000), but if we did, it would look like more, wouldn't it? Even if it doesn't depend on n.

It looks to me that when we discuss source code edits, 5 or 6 could already be considered large.

Layers #

Although software design thought leaders have denounced layered software architecture more than a decade ago, I don't entirely agree with that position. That, however, is a topic for a different article. In any case, I still regularly see examples of design that involves a UI DTO, a Domain Model, and a Data Access layer.

As I enumerated in 2012, a simple operation, such as adding a label field, involves at least six steps.

- "A Label column must be added to the database schema and the DbTrack class.

- "A Label property must be added to the Track class.

- "The mapping from DbTrack to Track must be updated.

- "A Label property must be added to the TopTrackViewModel class.

- "The mapping from Track to TopTrackViewModel must be updated.

- "The UI must be updated."

People often complain about all the seemingly redundant work involved with such layering, and I don't blame them. At least, if there's no clear motivation for a design like that, and no evident benefit, it looks like redundant work. While you can make good use of separating concerns across layers, that's outside the scope of this article. In the naive way most often employed, it seems like mindless ceremony.

Even so, how would we denote the above enumeration in terms of big-O notation? Adding a label field is an O(1) edit.

How so? Adding, changing, or deleting a field in a particular database table always entails the same number of steps (six) as outlined above. If, in addition to the Track table you want to add, say, an Album table, you create it according to the three-layer model. This again means that every edit of that table involves six steps. It's still O(1), with 1~6, but already it hurts.

Apparently, six may be a 'large constant'.

Linear edits #

So far, we've exclusively examined multiple examples of O(1) edits. Some of them, particularly the layered-architecture example, may seem counterintuitive at first. If it requires editing six different 'blocks' of code to make a single change (not counting tests!) is still O(1), then does anything constitute O(n), or any other kind of relationship?

To be realistic, I don't think we're in an analytical regime that allows us fine distinctions like identifying any kind of code organization to be, say O(lg n) or O(n lg n). On the other hand, examples of O(n) abound.

Every time you run into the Shotgun Surgery anti-pattern, you are looking at O(n) edits. As a simple example, consider poorly-factored logging, as for example shown initially in Repeatable execution. In such situations, you have n classes that log. If you need to change how logging is done, you must change n classes.

More generally, the main (unstated) goal of the DRY principle is to turn O(n) edits into O(1) edits.

Every junior developer already knows this. Notwithstanding, there's a category of code where even senior programmers routinely forget this.

Linear test coupling #

When it comes to automated testing, many developers treat test code stepmotherly. The most common mistake is the misguided notion that copy-and-paste code is fine in test code. It's not. Duplicated test code means that when you make a change in the System Under Test, n tests break, and you will have to fix each one individually, a clear O(n) edit (where n is the number of tests).

A more subtle example of an O(n) test maintenance burden can be found in test code that uses dynamic mocks. When you use a configurable mock object, each test contains isolated configuration code related to that specific test.

Let's look at an example. Consider the Moq-based tests from An example of interaction-based testing in C#. One test contains this Assert phase:

readerTD .Setup(r => r.Lookup(user.Id.ToString())) .Returns(Result.Success<User, IUserLookupError>(user)); readerTD .Setup(r => r.Lookup(otherUser.Id.ToString())) .Returns(Result.Success<User, IUserLookupError>(otherUser));

Another test arranges the same two Test Doubles, but configures the second differently.

readerTD .Setup(r => r.Lookup(user.Id.ToString())) .Returns(Result.Success<User, IUserLookupError>(user)); readerTD .Setup(r => r.Lookup(otherUserId)) .Returns(Result.Error<User, IUserLookupError>( UserLookupError.InvalidId));

Yet more tests arrange the System Under Test (SUT) in other combinations. Refer to the article for the full example.

Such tests don't contain duplication per se, but each test is coupled to the SUT's dependencies. When you change one of the interfaces, you break O(n) tests, and you have to fix each one individually.

As suggested earlier in the article, this is the reason to favour Fake Objects. While an interface change may still break the tests, the effort to correct them is O(1) edits.

Two kinds of coupling #

The big-O perspective on coupling suggests that there are two kinds of coupling: O(1) coupling and O(n) coupling. We can find duplication in both categories.

In the O(1) case, duplication is somehow limited. It may be that you are following the rule of three. This allows two copies of a piece of code to exist. It may be that you've made a particular architectural decision, such as using Fake Objects for testing (triplication), or using layered architecture (sextuplication). In these cases, there's a fixed number of edits that you have to make, and in principle, you should know where to make them.

I tend to be less concerned about this kind of coupling because it's manageable. In many cases, you may be able to lean on the compiler to guide you through the task of making a change. In other cases, you could have a checklist. Consider the above example of layered architecture. A checklist would enumerate the six separate steps you need to perform. Once you've checked off all six, you're done.

It may be slow, tedious work, but it's generally safe, because you are unlikely to forget a spot.

The O(n) case is where real trouble lies. This is the case when you copy and paste a snippet of code every time you need it somewhere new. When, later, you discover that there's a bug in the original 'source', you need to find all the places it occurs. Typical copy-paste code is often slightly modified after paste, so a naive search-and-replace strategy is likely to miss some instances.

Of course, if you've copied a whole method, function, class, or module, you may still be able to find it by name, but if you've only copied an unnamed block of code, that will not work either.

Not all edits are equally difficult #

To be fair, we should acknowledge that not all edit are equally difficult. There are kinds of changes you can automate. Most modern code editors come with refactoring support. In the case of testing with dynamic mocks, for example, you can rename methods, rearrange parameter lists, or remove a parameter.

Even so, some edits are harder. Changing the return type of a method tends to break calling code in most high-ceremony languages. Likewise, changing a primitive parameter (an integer, a Boolean, a string) to a complex object is non-trivial, as is adding a parameter with no obvious good default value. This is when O(n) coupling hurts.

Limitations #

So far, we've considered O(1) and O(n) edits. Are there O(lg n) edits, O(n2), or even O(2n) edits?

I can't rule it out, and if the reader can furnish some convincing examples, I'd be keen to learn about them. To be honest, though, I'm not sure it's that helpful. One could perhaps construe an example where inheritance creates a quadratic growth of subclasses, because someone is trying to model two independent features in a single inheritance tree. This, however, is just bad design, and we don't need the big-O lens to tell us that.

Conclusion #

As a thought experiment, one may adopt big-O notation as a viewpoint on code organisation. This seems particularly valuable when distinguishing between benign and malignant duplication. Duplication usually entails coupling. For a 'code architect', one of the most important tasks is to reduce, or at least control, coupling.

Some coupling is of the order O(1). Hidden in this notation is a constant, which may indicate that a change can be made with a single edit, two edits, six edits, and so on. Even if the actual number is 'large', you can put tools in place to minimize risk: A simple checklist may be enough, or perhaps you can leverage a static type system.

Other coupling is of the order O(n). Here, a single change must be made in O(n) different places, where n tends to grow over time, and there's no clear way to systematically find and identify them all. This kind of coupling strikes me as more dangerous than O(1) coupling.

When I sometimes seem to have a cavalier attitude to duplication, it's likely because I've already subconsciously identified a particular duplication as of the order O(1).

Git integration is ten years away

We'll get commercial nuclear fusion earlier.

Although, as I've described earlier, I tend to be conservative about updating my laptop, I tend to make exceptions for Visual Studio and Visual Studio Code. I was recently perusing the "what's new" notes after updating one or the other, and among all the new AI capabilities that I'm not interested in, I noticed something else: 'improved Git integration.'

As I reflected on that, a thought occurred to me. It seems to me that I've seen these update notes for at least a decade. Improved Git integration.

I'm not even exaggerating. Git support for Visual Studio was announced in 2013. It has, indeed, been around for a long time, and I've been blissfully ignoring it throughout. Even so, it struck me when reading release notes in 2025, that the product in question had improved Git integration.

Is it not done yet?

Apparently not.

It wasn't done ten years ago? Is there any reason to believe that it's done now? Or are we witnessing some reverse Lindy effect? The longer something has been in development, the longer you may expect it to be in development yet?

Sarcasm aside, you don't need Git integration in your development environment. Do yourself a favour and learn the fundamentals of Git. It takes a few hours to learn the basics, a few days to become more comfortable with it, but from then, no 'integration' need hold you back. You don't have to wait for the next update. Use Git tactically today.

Test-specific Eq

Adding Eq instances for better assertions.

Most well-written unit tests follow some variation of the Arrange Act Assert pattern. In the Assert phase, you may write a sequence of assertions that verify different aspects of what 'success' means. Even so, it boils down to this: You check that the expected outcome is equal to the actual outcome. Some testing frameworks like to turn the order around, but the idea remains the same. After all, equality is symmetric.

The ideal assertion is one that simply checks that actual is equal to expected. Some languages allow custom infix operators, in which case it's natural to define this fundamental assertion as an operator, such as @?=.

Since this is Haskell, however, the @?= operator comes with type constraints. Specifically, what we compare must be an Eq instance. In other words, the type in question must support the == operator. What do you do when a type is no Eq instance?

No Eq #

In a recent article you saw how a complicated test induced a tautological assertion. The main reason that the test was complicated was that the values involved were not Eq instances.

This got me thinking: Might test-specific equality help?

The easiest way to find out is to try. In this article, you'll see how that experiment turns out. First, however, you need a quick introduction to the problem space. The task at hand was to implement a cellular automaton, ostensibly modelling Galápagos finches meeting. When two finches encounter each other, they play out a game of Prisoner's Dilemma according to a strategy implemented in a domain-specific language.

Specifically, a finch is modelled like this:

data Finch = Finch { finchID :: Int, finchHP :: HP, finchRoundsLeft :: Rounds, -- The colour is used for visualisation, but has no semantic significance. finchColour :: Colour, -- The current strategy. finchStrategy :: Strategy, -- The expression that is evaluated to produce the strategy. finchStrategyExp :: Exp }

The Finch data type is not an Eq instance. The reason is that Strategy is effectively a free monad over this functor:

data EvalOp a

= ErrorOp Error

| MeetOp (FinchID -> a)

| GroomOp (Bool -> a)

| IgnoreOp (Bool -> a)

Since EvalOp is a sum of functions, it can't be an Eq instance, and this then applies transitively to Finch, as well as the CellState container that keeps track of each cell in the cellular grid:

data CellState = CellState { cellFinch :: Maybe Finch, cellRNG :: StdGen }

An important part of working with this particular code base is that the API is given, and must not be changed.

Given these constraints and data types, is there a way to improve test assertions?

Smelly tests #

The lack of Eq instances makes it difficult to write simple assertions. The worst test I wrote is probably this, making use of a predefined example Finch value named flipflop:

testCase "Cell 1 reproduces" $ let cell1 = Galapagos.CellState (Just flipflop) (mkStdGen 0) cell2 = Galapagos.CellState Nothing (mkStdGen 6) -- seeded to reprod actual = Galapagos.reproduce Galapagos.defaultParams (cell1, cell2) in do -- Sanity check on first finch. Unfortunately, CellState is no Eq -- instance, so we can't just compare the entire record. Instead, -- using HP as a sample: (Galapagos.finchHP <$> Galapagos.cellFinch (fst actual)) @?= Just 20 -- New finch should have HP from params: (Galapagos.finchHP <$> Galapagos.cellFinch (snd actual)) @?= Just 14 -- New finch should have lifespan from params: (Galapagos.finchRoundsLeft <$> Galapagos.cellFinch (snd actual)) @?= Just 23 -- New finch should have same colour as parent: ( Galapagos.finchColour <$> Galapagos.cellFinch (snd actual)) @?= Galapagos.finchColour <$> Galapagos.cellFinch cell1 -- More assertions, described by their error messages: ( (Galapagos.finchID <$> Galapagos.cellFinch (fst actual)) /= (Galapagos.finchID <$> Galapagos.cellFinch (snd actual))) @? "Finches have same ID, but they should be different." ((/=) `on` Galapagos.cellRNG) cell2 (snd actual) @? "New cell 2 should have an updated RNG."

As you can tell from the apologies all these assertions leave something to be desired. The first assertion uses finchHP as a proxy for the entire finch in cell1, which is not supposed to change. Instead of an assertion for each of the first finch's attributes, the test 'hopes' that if finchHP didn't change, then so didn't the other values.

The test then proceeds to verify various fields of the new finch in cell2, checking them one by one, since the lack of Eq makes it impossible to simply check that the actual value is equal to the expected value.

In comparison, the test you saw in the previous article is almost pretty. It uses another example Finch value named cheater.

testCase "Cell 1 does not reproduce" $ let cell1 = Galapagos.CellState (Just cheater) (mkStdGen 0) cell2 = Galapagos.CellState Nothing (mkStdGen 1) -- seeded: no repr. actual = Galapagos.reproduce Galapagos.defaultParams (cell1, cell2) in do -- Sanity check that cell 1 remains, sampling on strategy: ( Galapagos.finchStrategyExp <$> Galapagos.cellFinch (fst actual)) @?= Galapagos.finchStrategyExp <$> Galapagos.cellFinch cell1 ( Galapagos.finchHP <$> Galapagos.cellFinch (snd actual)) @?= Nothing

The apparent simplicity is mostly because at that time, I'd almost given up on more thorough testing. In this test, I chose finchStrategyExp as a proxy for each value, and 'hoped' that if these properties behaved as expected, other attributes would, too.

Given that I was following test-driven development and thus engaging in grey-box testing, I had reason to believe that the implementation was correct if the test passes.

Still, those tests exhibit more than one code smell. Could test-specific equality be the answer?

Test utilities for finches #

The fundamental problem is that the finchStrategy field prevents Finch from being an Eq instance. Finding a way to compare Strategy values seems impractical. A more realistic course of action might be to compare all other fields. One option is to introduce a test-specific type with proper Eq and Show instances.

data FinchEq = FinchEq { feqID :: Int , feqHP :: Galapagos.HP , feqRoundsLeft :: Galapagos.Rounds , feqColour :: Galapagos.Colour , feqStrategyExp :: Exp } deriving (Eq, Show)

This data type only exists in the test code base. It has all the fields of Finch, except finchStrategy.

While I could use it as-is, it quickly turns out that a helper function to turn a CellState value into a FinchEq value would also be useful.

finchEq :: Galapagos.Finch -> FinchEq finchEq f = FinchEq { feqID = Galapagos.finchID f , feqHP = Galapagos.finchHP f , feqRoundsLeft = Galapagos.finchRoundsLeft f , feqColour = Galapagos.finchColour f , feqStrategyExp = Galapagos.finchStrategyExp f } cellFinchEq :: Galapagos.CellState -> Maybe FinchEq cellFinchEq = fmap finchEq . Galapagos.cellFinch

Finally, the System Under Test (the reproduce function) takes a tuple as input, and returns a tuple of the same type as output. To avoid some code duplication, it's practical to introduce a data type that can map over both components.

newtype Pair a = Pair (a, a) deriving (Eq, Show, Functor)

This newtype wrapper makes it possible to map both the first and the second component of a pair (a two-tuple) using a single projection, since Pair is a Functor instance.

That's all the machinery required to rewrite the two tests shown above.

Improving the first test #

The first test may be rewritten as this:

testCase "Cell 1 reproduces" $ let cell1 = Galapagos.CellState (Just flipflop) (mkStdGen 0) cell2 = Galapagos.CellState Nothing (mkStdGen 6) -- seeded to reprod actual = Galapagos.reproduce Galapagos.defaultParams (cell1, cell2) expected = Just $ finchEq $ flipflop { Galapagos.finchID = -1142203427417426925 -- From Character. Test , Galapagos.finchHP = 14 , Galapagos.finchRoundsLeft = 23 } in do (cellFinchEq <$> Pair actual) @?= Pair (cellFinchEq cell1, expected) ((/=) `on` Galapagos.cellRNG) cell2 (snd actual) @? "New cell 2 should have an updated RNG."

That's still a bit of code. If you're used to C# or Java code, you may not bat an eyelid over a fifteen-line code block (that even has a few blank lines), but fifteen lines of Haskell code is still significant.

There are compound reasons for this. One is that the Galapagos module is a qualified import, which makes the code more verbose than it otherwise could have been. It doesn't help that I follow a strict rule of staying within an 80-character line width.

That said, this version of the test has stronger assertions than before. Notice that the first assertion compares two Pairs of FinchEq values. This means that all five comparable fields of each finch is compared against the expected value. Since the assertion compares two Pairs, that's ten comparisons in all. The previous test only made five comparisons on the finches.

The second assertion remains as before. It's there to ensure that the System Under Test (SUT) remembers to update its pseudo-random number generator.

Perhaps you wonder about the expected values. For the finchID, hopefully the comment gives a hint. I originally set this value to 0, ran the test, observed the actual value, and used what I had observed. I could do that because I was refactoring an existing test that exercised an existing SUT, following the rules of empirical Characterization Testing.

The finchID values are in practice randomly generated numbers. These are notoriously awkward in test contexts, so I could also have excluded that field from FinchEq. Even so, I kept the field, because it's important to be able to verify that the new finch has a different finchID than the parent that begat it.

Derived values #

Where do the magic constants 14 and 23 come from? Although we could use comments to explain their source, another option is to use Derived Values to explicitly document their origin:

testCase "Cell 1 reproduces" $ let cell1 = Galapagos.CellState (Just flipflop) (mkStdGen 0) cell2 = Galapagos.CellState Nothing (mkStdGen 6) -- seeded to reprod actual = Galapagos.reproduce Galapagos.defaultParams (cell1, cell2) expected = Just $ finchEq $ flipflop { Galapagos.finchID = -1142203427417426925 -- From Character. Test , Galapagos.finchHP = Galapagos.startHP Galapagos.defaultParams , Galapagos.finchRoundsLeft = Galapagos.lifespan Galapagos.defaultParams } in do (cellFinchEq <$> Pair actual) @?= Pair (cellFinchEq cell1, expected) ((/=) `on` Galapagos.cellRNG) cell2 (snd actual) @? "New cell 2 should have an updated RNG."

We now learn that the finchHP value originates from the startHP value of the defaultParams, and similarly for finchRoundsLeft.

To be honest, I'm not sure that this is an improvement. It makes the test more abstract, and if we wish that tests may serve as executable documentation, concrete example values may be easier to understand. Besides, this gets uncomfortably close to duplicating the actual implementation code contained in the SUT.

This variation only serves as an exploration of alternatives. I would strongly consider rolling this change back, and instead add some comments to the magic numbers.

Improving the second test #

The second test improves better.

testCase "Cell 1 does not reproduce" $ let cell1 = Galapagos.CellState (Just cheater) (mkStdGen 0) cell2 = Galapagos.CellState Nothing (mkStdGen 1) -- seeded: no repr. actual = Galapagos.reproduce Galapagos.defaultParams (cell1, cell2) in (cellFinchEq <$> Pair actual) @?= Pair (cellFinchEq cell1, Nothing)

Not only is it shorter, the assertion is much stronger. It achieves the ideal of verifying that the actual value is equal to the expected value, comparing five data fields on each of the two finches.

Comparing cells #

The reproduce function uses the pseudo-random number generators embedded in the CellState data type to decide whether a finch reproduces in a given round. Thus, the number generators change in deterministic, but by human cognition unpredictable, ways. It makes sense to exclude the generators from the assertions, apart from the above assertion that verifies the change itself.

Other functions in the Galapagos module also work on CellState values, but are entirely deterministic; that is, they don't make use of the pseudo-random number generators. One such function is groom, which models what happens when two finches meet and play out their game of Prisoner's Dilemma by deciding to groom the other for parasites, or not. The function has this type:

groom :: Params -> (CellState, CellState) -> (CellState, CellState)

By specification, this function has no random behaviour, which means that we expect the number generators to stay the same. Even so, due to the lack of an Eq instance, comparing cells is difficult.

testCase "Groom when right cell is empty" $ let cell1 = Galapagos.CellState (Just flipflop) (mkStdGen 0) cell2 = Galapagos.CellState Nothing (mkStdGen 1) actual = Galapagos.groom Galapagos.defaultParams (cell1, cell2) in do ( Galapagos.finchHP <$> Galapagos.cellFinch (fst actual)) @?= Galapagos.finchHP <$> Galapagos.cellFinch cell1 ( Galapagos.finchHP <$> Galapagos.cellFinch (snd actual)) @?= Nothing

Instead of comparing cells, this test only considers the contents of each cell, and it only compares a single field, finchHP, as a proxy for comparing the more complete data structure.

With FinchEq we have a better way of comparing two finches, but we don't have to stop there. We may introduce another test-utility type that can compare cells.

data CellStateEq = CellStateEq { cseqFinch :: Maybe FinchEq , cseqRNG :: StdGen } deriving (Eq, Show)

A helper function also turns out to be useful.

cellStateEq :: Galapagos.CellState -> CellStateEq cellStateEq cs = CellStateEq { cseqFinch = cellFinchEq cs , cseqRNG = Galapagos.cellRNG cs }

We can now rewrite the test to compare both cells in their entirety (minus the finchStrategy).

testCase "Groom when right cell is empty" $ let cell1 = Galapagos.CellState (Just flipflop) (mkStdGen 0) cell2 = Galapagos.CellState Nothing (mkStdGen 1) actual = Galapagos.groom Galapagos.defaultParams (cell1, cell2) in (cellStateEq <$> Pair actual) @?= cellStateEq <$> Pair (cell1, cell2)

Again, the test is both simpler and stronger.

A fly in the ointment #

Introducing FinchEq and CellStateEq allowed me to improve most of the tests, but a few annoying issues remain. The most illustrative example is this test of the core groom behaviour, which lets two example Finch values named samaritan and cheater interact.

testCase "Groom two finches" $ let cell1 = Galapagos.CellState (Just samaritan) (mkStdGen 0) cell2 = Galapagos.CellState (Just cheater) (mkStdGen 1) actual = Galapagos.groom Galapagos.defaultParams (cell1, cell2) expected = Just <$> Pair ( finchEq $ samaritan { Galapagos.finchHP = 16 } , finchEq $ cheater { Galapagos.finchHP = 13 } ) in (cellFinchEq <$> Pair actual) @?= expected

This test ought to compare cells with CellStateEq, but only compares finches. The practical reason is that defining the expected value as a pair of cells entails embedding the expected finches in their respective cells. This is possible, but awkward, due to the nested nature of the data types.

It's possible to do something about that, too, but that's the topic for another article.

Conclusion #

If a test is difficult to write, it may be a symptom that the System Under Test (SUT) has an API which is difficult to use. When doing test-driven development you may want to reconsider the API. Is there a way to model the desired data and behaviour in such a way that the tests become simpler? If so, the API may improve in general.

Sometimes, however, you can't change the SUT API. Perhaps it's already given. Perhaps improving it would be a breaking change. Or perhaps you simply can't think of a better way.

An alternative to changing the SUT API is to introduce test utilities, such as types with test-specific equality. This is hardly better than improving the SUT API, but may be useful in those situations where the best option is unavailable.

Tautological assertions are not always caused by aliasing

You can also make mistakes that compile in Haskell.