Set is not a functor by Mark Seemann

Sets aren't functors. An example for object-oriented programmers.

This article is an instalment in an article series about functors. The way functors are frequently presented to programmers is as a generic container (Foo<T>) equipped with a translation method, normally called map, but in C# idiomatically called Select.

It'd be tempting to believe that any generic type with a Select method is a functor, but it takes more than that. The Select method must also obey the functor laws. This article shows an example of a translation that violates the second functor law.

Mapping sets #

The .NET Base Class Library comes with a class called HashSet<T>. This generic class implements IEnumerable<T>, so, via extension methods, it has a Select method.

Unfortunately, that Select method isn't a structure-preserving translation of sets. The problem is that it treats sets as enumerable sequences, which implies an order to elements that isn't part of a set's structure.

In order to understand what the problem is, consider this xUnit.net test:

[Fact] public void SetAsEnumerableSelectLeadsToWrongConclusions() { var set1 = new HashSet<int> { 1, 2, 3 }; var set2 = new HashSet<int> { 3, 2, 1 }; Assert.True(set1.SetEquals(set2)); Func<int, int> id = x => x; var seq1 = set1.AsEnumerable().Select(id); var seq2 = set2.AsEnumerable().Select(id); Assert.False(seq1.SequenceEqual(seq2)); }

This test creates two sets, and by using a Guard Assertion demonstrates that they're equal to each other. It then proceeds to Select over both sets, using the identity function id. The return values aren't HashSet<T> objects, but rather IEnumerable<T> sequences. Due to an implementation detail in HashSet<T>, these two sequences are different, because they were populated in reverse order of each other.

The problem is that the Select extension method has the signature IEnumerable<TResult> Select<T, TResult>(IEnumerable<T>, Func<T, TResult>). It doesn't operate on HashSet<T>, but instead treats it as an ordered sequence of elements. A set isn't intrinsically ordered, so that's not the translation you need.

To be clear, IEnumerable<T> is a functor (as long as the sequence is referentially transparent). It's just not the functor you're looking for. What you need is a method with the signature HashSet<TResult> Select<T, TResult>(HashSet<T>, Func<T, TResult>). Fortunately, such a method is trivial to implement:

public static HashSet<TResult> Select<T, TResult>( this HashSet<T> source, Func<T, TResult> selector) { return new HashSet<TResult>(source.AsEnumerable().Select(selector)); }

This extension method offers a proper Select method that translates one HashSet<T> into another. It does so by enumerating the elements of the set, then using the Select method for IEnumerable<T>, and finally wrapping the resulting sequence in a new HashSet<TResult> object.

This is a better candidate for a translation of sets. Is it a functor, then?

Second functor law #

Even though HashSet<T> and the new Select method have the correct types, it's still only a functor if it obeys the functor laws. It's easy, however, to come up with a counter-example that demonstrates that Select violates the second functor law.

Consider a pair of conversion methods between string and DateTimeOffset:

public static DateTimeOffset ParseDateTime(string s) { DateTimeOffset dt; if (DateTimeOffset.TryParse(s, out dt)) return dt; return DateTimeOffset.MinValue; } public static string FormatDateTime(DateTimeOffset dt) { return dt.ToString("yyyy'-'MM'-'dd'T'HH':'mm':'sszzz"); }

The first method, ParseDateTime, converts a string into a DateTimeOffset value. It tries to parse the input, and returns the corresponding DateTimeOffset value if this is possible; for all other input values, it simply returns DateTimeOffset.MinValue. You may dislike how the method deals with input values it can't parse, but that's not important. In order to prove that sets aren't functors, I just need one counter-example, and the one I'll pick will not involve unparseable strings.

The FormatDateTime method converts any DateTimeOffset value to an ISO 8601 string.

The DateTimeOffset type is the interesting piece of the puzzle. In case you're not intimately familiar with it, a DateTimeOffset value contains a date, a time, and a time-zone offset. You can, for example create one like this:

> new DateTimeOffset(2018, 4, 17, 15, 9, 55, TimeSpan.FromHours(2)) [17.04.2018 15:09:55 +02:00]

This represents April 17, 2018, at 15:09:55 at UTC+2. You can convert that value to UTC:

> new DateTimeOffset(2018, 4, 17, 15, 9, 55, TimeSpan.FromHours(2)).ToUniversalTime() [17.04.2018 13:09:55 +00:00]

This value clearly contains different constituent elements, but it does represent the same instant in time. This is how DateTimeOffset implements Equals. These two object are considered equal, as the following test will demonstrate.

In a sense, you could argue that there's some sense in implementing equality for DateTimeOffset in that way, but this unusual behaviour provides just the counter-example that demonstrates that sets aren't functors:

[Fact] public void SetViolatesSecondFunctorLaw() { var x = "2018-04-17T13:05:28+02:00"; var y = "2018-04-17T11:05:28+00:00"; Assert.Equal(ParseDateTime(x), ParseDateTime(y)); var set = new HashSet<string> { x, y }; var l = set.Select(ParseDateTime).Select(FormatDateTime); var r = set.Select(s => FormatDateTime(ParseDateTime(s))); Assert.False(l.SetEquals(r)); }

This passing test provides the required counter-example. It first creates two ISO 8601 representations of the same instant. As the Guard Assertion demonstrates, the corresponding DateTimeOffset values are considered equal.

In the act phase, the test creates a set of these two strings. It then performs two round-trips over DateTimeOffset and back to string. The second functor law states that it shouldn't matter whether you do it in one or two steps, but it does. Assert.False passes because l is not equal to r. Q.E.D.

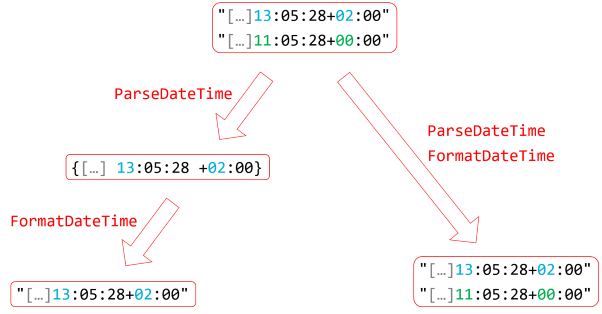

An illustration #

The problem is that sets only contain one element of each value, and due to the way that DateTimeOffset interprets equality, two values that both represent the same instant are collapsed into a single element when taking an intermediary step. You can illustrate it like this:

In this illustration, I've hidden the date behind an ellipsis in order to improve clarity. The date segments are irrelevant in this example, since they're all identical.

You start with a set of two string values. These are obviously different, so the set contains two elements. When you map the set using the ParseDateTime function, you get two DateTimeOffset values that .NET considers equal. For that reason, HashSet<DateTimeOffset> considers the second value redundant, and ignores it. Therefore, the intermediary set contains only a single element. When you map that set with FormatDateTime, there's only a single element to translate, so the final set contains only a single string value.

On the other hand, when you map the input set without an intermediary set, each string value is first converted into a DateTimeOffset value, and then immediately thereafter converted back to a string value. Since the two resulting strings are different, the resulting set contains two values.

Which of these paths is correct, then? Both of them. That's the problem. When considering the semantics of sets, both translations produce correct results. Since the results diverge, however, the translation isn't a functor.

Summary #

A functor must not only preserve the structure of the data container, but also of functions. The functor laws express that a translation of functions preserves the structure of how the functions compose, in addition to preserving the structure of the containers. Mapping a set doesn't preserve those structures, and that's the reason that sets aren't functors.

P.S. #

2019-01-09. There's been some controversy around this post, and more than one person has pointed out to me that the underlying reason that the functor laws are violated in the above example is because DateTimeOffset behaves oddly. Specifically, its Equals implementation breaks the substitution property of equality. See e.g. Giacomo Citi's response for details.

The term functor originates from category theory, and I don't claim to be an expert on that topic. It's unclear to me if the underlying concept of equality is explicitly defined in category theory, but it wouldn't surprise me if it is. If that definition involves the substitution property, then the counter-example presented here says nothing about Set as a functor, but rather that DateTimeOffset has unlawful equality behaviour.

Next: Applicative functors.

Comments

The Problem here is not the HashSet, but the DateTimeOffset Class. It defines Equality loosely, so Time-Comparison is possible between different Time-Zones. The Functor Property can be restored by applying a stricter Equality Comparer like this one:

var l = set.Select(ParseDateTime, StrictDateTimeOffsetComparer._).Select(FormatDateTime); /// <summary> Compares both <see cref="DateTimeOffset.Offset"/> and <see cref="DateTimeOffset.UtcTicks"/> </summary> public class StrictDateTimeOffsetComparer : IEqualityComparer<DateTimeOffset> { public bool Equals(DateTimeOffset x, DateTimeOffset y) => x.Offset.Equals(y.Offset) && x.UtcTicks == y.UtcTicks; public int GetHashCode(DateTimeOffset obj) => HashCode.Combine(obj.Offset, obj.UtcTicks); /// <summary> Singleton Instance </summary> public static readonly StrictDateTimeOffsetComparer _ = new(); StrictDateTimeOffsetComparer(){} }As for preserving Referential Transparency, the Distinction between Equality and Identity is important. By Default, Classes implement 'Equals' and '==' using ReferenceEquals which guarantees Substitution. Structs don't have a Reference unless they are boxed, instead they are copied and usually have Value Semantics. To be truly 'referentially transparent' though, Equality must be based on ALL Fields. When someone overrides Equals with a weaker Equivalence Relation than ReferenceEquals, it is their Responsibility to preserve Substitution. No Library Author can cover all possible application cases for HashSet.Matt, thank you for writing.

DateTimeOffsetalready defines the EqualsExact method. Wouldn't it be easier to use that?In context, you are correct; you can pick whatever example you want to create a counter-example. However, your counter-example does not prove that

HashSet<>is not a functor.We often say that a type is or isn't a functor. That is not quite right. It is more correct to say that a type

T<>and a function with inputsT<A>andAand outputT<B>are or are not a functor. Then I think it is reasonable to say some type is a functor if (and only if) there exists a function such that the type and that functor are a functor. In that case, to conclude thatHashSet<>is not a functor requires one to prove that, for all functionsf, the pairHashSet<>andfare not a functor. Because of the universal quantification, this cannot be achieved via a single counter-example.Your counter-example shows that the type

HashSet<>and your function that you calledSelectis not a functor. YourSelectfunction uses this constructor overload ofHashSet<>, which eventually usesEqualityComparer<T>.Defaultin places like here and here. The instance ofEqualityComparer<DateTimeOffset>.Defaultimplements itsEqualsmethod viaDateTimeOffset.Equals. The comments by Giacomo Citi and others explained "why" yourSelectfunction (and the typeHashSet<>) doesn't satisfy the second functor law: you picked a constructor overload ofHashSet<>that uses an implementation ofIEqualityComparer<DateTimeOffset>that depends onDateTimeOffset.Equals, which doesn't satisfy the substitution property.I think this is a red herring. Microsoft can implement

HashSet<>however it wants and you can implement yourSelectfunction however you want. Then the pair are either a functor or not. Independent of this is that Microsoft gets to define the contract forIEqualityComparer<>.Equals. The documentation states that a valid implementation must be reflexive, symmetric, and transitive but does not require that the substitution property is satisifed.I think the correct question is this: Is

HashSet<>a functor?...which is equivalent to: Does there exist a function such thatHashSet<>and that function are a functor? I think the answer is "yes".Implement

Selectby calling the constructor overload ofHashSet<>that takes an instance ofIEnumerable<>as well as an instance ofIEqualityComparer<>. For the second argument, provide an instance that implementsEqualsby always returningfalse(and it suffices to implementGetHashCodeby returning a constant). I claim thatHashSet<>and that function are a functor. In fact, I further claim that this functor is isomorphic to the functorIEnumerable<>(with the functionEnumerable.Select). That doesn't make it a very interesting functor, but it is a functor nonetheless. (Also, notice that this implementation ofEqualsis not reflexive, but I still used it to create a functor.)Tyson, thank you for writing. Yes, I agree with most of what you write. As I added in the P.S., I'm aware that this post draws the wrong conclusions. I also understand why.

It's true that one way to think of a functor is a type and an associated function. When I (and others) sometimes fall into the trap of directly equating types with functors, it's because this is the most common implementation of functors (and monads) in statically typed programming. This is probably most explicit in Haskell, where a particular functor is explicitly associated with a type. This has the implication that in order to distinguish between multiple functors, Haskell comes with all sort of wrapper types. You mostly see this in the context of semigroups and monoids, where the Sum and Product wrappers exist only to distinguish between two monoids over the same type (numbers).

You could imagine something similar happening with Either and tuple bifunctors. By conventions (and because of a bit pseudo-principled hand-waving), we conventionally pick one of the their dimensions for the 'functor instance'. For example, we pick the right dimension of Either for the functor instance. In both Haskell, F#, and C#, this enables certain syntax, such as Haskell

donotation, F# computation expressions, or C# query syntax.If we wanted to instead make mapping over, say, left, the 'functor instance', we can't do that without throwing away the language support for the right side. The solution is to introduce a new type that comes with the desired function associated. This enables the compiler to distinguish between two (or more) functors over what would otherwise be the same type.

That aside, can we resolve the issue in the way that you suggest? Possibly. I haven't thought deep and long about it, but what you write sounds plausible.

For anyone who wants to use such a set functor for real code, I'd suggest wrapping it in another type, since relying on client developers to use the 'correct' constructor overload seems too brittle.

Well, yes, but since you have to implement a proper matching HashCode Function anyway, I thought it would be more obvious to write a matching Equals Function too.

Ah, so you're proposing to subclass HashSet<DateTimeOffset> and pass the proper EqualityComparer to the base class. Alright, that would be a proper Functor then.