Better abstractions revisited by Mark Seemann

How do you design better abstractions? A retrospective look on an old article for object-oriented programmers.

About a decade ago, I had already been doing test-driven development (TDD) and used Dependency Injection for many years, but I'd started to notice some patterns about software design. I'd noticed that interfaces aren't abstractions and that TDD isn't a design methodology. Sometimes, I'd arrive at interfaces that turned out to be good abstractions, but at other times, the interfaces I created seemed to serve no other purpose than enabling unit testing.

In 2010 I thought that I'd noticed some patterns for good abstractions, so I wrote an article called Towards better abstractions. I still consider it a decent attempt at communicating my findings, but I don't think that I succeeded. My thinking on the subject was still too immature, and I lacked a proper vocabulary.

While I had hoped that I would be able to elaborate on such observations, and perhaps turn them into heuristics, my efforts soon after petered out. I moved on to other things, and essentially gave up on this particular research programme. Years later, while trying to learn category theory, I suddenly realised that mathematical disciplines like category theory and abstract algebra could supply the vocabulary. After some further work, I started publishing a substantial and long-running article series called From design patterns to category theory. It goes beyond my initial attempt, but it finally enabled me to crystallise those older observations.

In this article, I'll revisit that old article, Towards better abstractions, and translate the vague terminology I used then, to the terminology presented in From design patterns to category theory.

The thrust of the old article is that if you can create a Composite or a Null Object from an interface, then it's likely to be a good abstraction. I still consider that a useful rule of thumb.

When can you create a Composite? When the abstraction gives rise to a monoid. When can you create a Null Object? When the abstraction gives rise to a monoid.

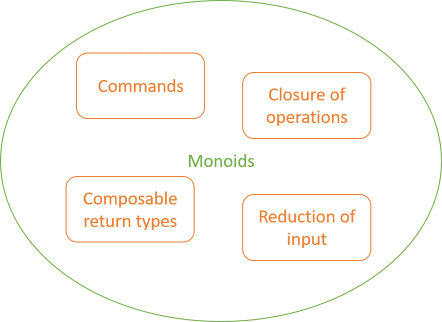

All the 'API shapes' I'd identified in Towards better abstractions form monoids.

Commands #

A Command seems to be universally identified by a method typically called Execute:

public void Execute()

From unit isomorphisms we know that methods with the void return type are isomorphic to (impure) functions that return unit, and that unit forms a monoid.

Furthermore, we know from function monoids that methods that return a monoid themselves form monoids. Therefore, Commands form monoids.

In early 2011 I'd already explicitly noticed that Commands are composable. Now I know the deeper reason for this: they're monoids.

Closure of operations #

In Domain-Driven Design, Eric Evans discusses the benefits of designing APIs that exhibit closure of operations. This means that a method returns the same type as all its input arguments. The simplest example is the one that I show in the old article:

public static T DoIt(T x)

That's just an endomorphism, which forms a monoid.

Another variation is a method that takes two arguments:

public static T DoIt(T x, T y)

This is a binary operation. While it's certainly a magma, in itself it's not guaranteed to be a monoid. In fact, Evans' colour-mixing example is only a magma, but not a monoid. You can, however, also view this as a special case of the reduction of input shape, below, where the 'extra' arguments just happen to have the same type as the return type. In that interpretation, such a method still forms a monoid, but it's not guaranteed to be meaningful. (Just like modulo 31 addition forms a monoid; it's hardly useful.)

The same sort of argument goes for methods with closure of operations, but more input arguments, like:

public static T DoIt(T x, T y, T z)

This sort of method is, however, rare, unless you're working in a stringly typed code base where methods look like this:

public static string DoIt(string x, string y, string z)

That's a different situation, though, because those strings should probably be turned into domain types that properly communicate their roles. Once you do that, you'll probably find that the method arguments have different types.

In any case, regardless of cardinality, you can view all methods with closure of operations as special cases of the reduction of input shape below.

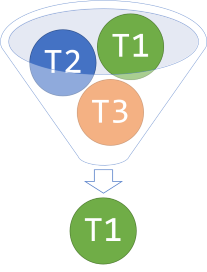

Reduction of input #

This is the part of the original article where my struggles with vocabulary began in earnest. The situation is when you have a method that looks like this, perhaps as an interface method:

public interface IInputReducer<T1, T2, T3> { T1 DoIt(T1 x, T2 y, T3 z); }

In order to stay true to the terminology of my original article, I've named this reduction of input generic example IInputReducer. The reason I originally called it reduction of input is that such a method takes a set of input types as arguments, but only returns a value of a type that's a subset of the set of input types. Thus, the method looks like it's reducing the range of input types to a single one of those types.

A realistic example could be a piece of HTTP middleware that defines an action filter as an interface that you can implement to intercept each HTTP request:

public interface IActionFilter { Task<HttpResponseMessage> ExecuteActionFilterAsync( HttpActionContext actionContext, CancellationToken cancellationToken, Task<HttpResponseMessage> continuation); }

This is a slightly modified version of an earlier version of the ASP.NET Web API. Notice that in this example, it's not the first argument's type that doubles as the return type, but rather the third and last argument. The reduction of input 'shape' can take an arbitrary number of arguments, and any of the argument types can double as a return type, regardless of position.

Returning to the generic IInputReducer example, you can easily make a Composite of it:

public class CompositeInputReducer<T1, T2, T3> : IInputReducer<T1, T2, T3> { private readonly IInputReducer<T1, T2, T3>[] reducers; public CompositeInputReducer(params IInputReducer<T1, T2, T3>[] reducers) { this.reducers = reducers; } public T1 DoIt(T1 x, T2 y, T3 z) { var acc = x; foreach (var reducer in reducers) acc = reducer.DoIt(acc, y, z); return acc; } }

Notice that you call DoIt on all the composed reducers. The arguments that aren't part of the return type, y and z, are passed to each call to DoIt unmodified, whereas the T1 value x is only used to initialise the accumulator acc. Each call to DoIt also returns a T1 object, so the acc value is updated to that object, so that you can use it as an input for the next iteration.

This is an imperative implementation, but as you'll see below, you can also implement the same behaviour in a functional manner.

For the sake of argument, pretend that you reorder the method arguments so that the method looks like this:

T1 DoIt(T3 z, T2 y, T1 x);

From Uncurry isomorphisms you know that a method like that is isomorphic to a function with the type 'T3 -> 'T2 -> 'T1 -> 'T1 (F# syntax). You can think of such a curried function as a function that returns a function that returns a function: 'T3 -> ('T2 -> ('T1 -> 'T1)). The rightmost function 'T1 -> 'T1 is clearly an endomorphism, and you already know that an endomorphism gives rise to a monoid. Finally, Function monoids informs us that a function that returns a monoid itself forms a monoid, so 'T2 -> ('T1 -> 'T1) forms a monoid. This argument applies recursively, because if that's a monoid, then 'T3 -> ('T2 -> ('T1 -> 'T1)) is also a monoid.

What does that look like in C#?

In the rest of this article, I'll revert the DoIt method signature to T1 DoIt(T1 x, T2 y, T3 z);. The monoid implementation looks much like the endomorphism code. Start with a binary operation:

public static IInputReducer<T1, T2, T3> Append<T1, T2, T3>( this IInputReducer<T1, T2, T3> r1, IInputReducer<T1, T2, T3> r2) { return new AppendedReducer<T1, T2, T3>(r1, r2); } private class AppendedReducer<T1, T2, T3> : IInputReducer<T1, T2, T3> { private readonly IInputReducer<T1, T2, T3> r1; private readonly IInputReducer<T1, T2, T3> r2; public AppendedReducer( IInputReducer<T1, T2, T3> r1, IInputReducer<T1, T2, T3> r2) { this.r1 = r1; this.r2 = r2; } public T1 DoIt(T1 x, T2 y, T3 z) { return r2.DoIt(r1.DoIt(x, y, z), y, z); } }

This is similar to the endomorphism Append implementation. When you combine two IInputReducer objects, you receive an AppendedReducer that implements DoIt by first calling DoIt on the first object, and then using the return value from that method call as the input for the second DoIt method call. Notice that y and z are just 'context' variables used for both reducers.

Just like the endomorphism, you can also implement the identity input reducer:

public class IdentityInputReducer<T1, T2, T3> : IInputReducer<T1, T2, T3> { public T1 DoIt(T1 x, T2 y, T3 z) { return x; } }

This simply returns x while ignoring y and z. The Append method is associative, and the IdentityInputReducer is both left and right identity for the operation, so this is a monoid. Since monoids accumulate, you can also implement an Accumulate extension method:

public static IInputReducer<T1, T2, T3> Accumulate<T1, T2, T3>( this IReadOnlyCollection<IInputReducer<T1, T2, T3>> reducers) { IInputReducer<T1, T2, T3> identity = new IdentityInputReducer<T1, T2, T3>(); return reducers.Aggregate(identity, (acc, reducer) => acc.Append(reducer)); }

This implementation follows the overall implementation pattern for accumulating monoidal values: start with the identity and combine pairwise. While I usually show this in a more imperative form, I've here used a proper functional implementation for the method.

The IInputReducer object returned from that Accumulate function has exactly the same behaviour as the CompositeInputReducer.

The reduction of input shape forms another monoid, and is therefore composable. The Null Object is the IdentityInputReducer<T1, T2, T3> class. If you set T1 = T2 = T3, you have the closure of operations 'shapes' discussed above; they're just special cases, so form at least this type of monoid.

Composable return types #

The original article finally discusses methods that in themselves don't look composable, but turn out to be so anyway, because their return types are composable. Without knowing it, I'd figured out that methods that return monoids are themselves monoids.

In 2010 I didn't have the vocabulary to put this into specific language, but that's all it says.

Summary #

In 2010 I apparently discovered an ad-hoc, informally specified, vaguely glimpsed, half-understood description of half of abstract algebra.

Riffs on Greenspun's tenth rule aside, things clicked for me once I started to investigate what category theory was about, and why it seemed so closely linked to Haskell. That's one of the reasons I started writing the From design patterns to category theory article series.

The patterns I thought that I could see in 2010 all form monoids, but there are many other universal abstractions from mathematics that apply to programming as well.