ploeh blog danish software design

Captive Dependency

A Captive Dependency is a dependency with an incorrectly configured lifetime. It's a typical and dangerous DI Container configuration error.

This post is the sixth in a series about Poka-yoke Design.

When you use a Dependency Injection (DI) Container, you should configure it according to the Register Resolve Release pattern. One aspect of configuration is to manage the lifetime of various services. If you're not careful, though, you may misconfigure lifetimes in such a way that a longer-lived service holds a shorter-lived service captive - often with subtle, but disastrous results. You could call this misconfiguration a Captive Dependency.

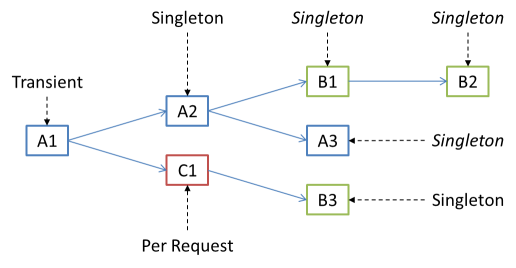

A major step in applying DI is to compose object graphs, and service lifetimes in object graphs are hierarchical:

This figure illustrates the configured and effective lifetimes of an object graph. Node A1 should have a Transient lifetime, which is certainly possible. A new instance of C1 should be created Per Request (if the object graph is part of a web application), which is also possible, because A1 has a shorter lifetime than Per Request. Similarly, only a single instance of B3 should ever be created, which is also possible, because the various instances of C1 can reuse the same B3 instance.

The A2 node also has a Singleton lifetime, which means that only a single instance should exist of this object. Because A2 holds references to B1 and A3, these two object are also effectively Singletons. It doesn't matter how you'd like the lifetimes of B1 and A3 to be: the fact is that the single instance of A2 holds on to its injected instances of B1 and A3 means that these instances are going to stick around as long as A2. This effect is transitive, so A2 also causes B2 to have an effective Singleton lifetime.

This can be problematic if, for example, B1, A3, or B2 aren't thread-safe.

Commerce example #

This may make more sense if you see this in a more concrete setting than just an object graph with A1, A2, B1, etc. nodes, so consider the introductory example from my book. It has a ProductService, which depends on an IProductRepository interface (actually, in the book, the Repository is an Abstract Base Class):

public class ProductService { private readonly IProductRepository repository; public ProductService(IProductRepository repository) { this.repository = repository; } // Other members go here... }

One implementation of IProductRepository is SqlProductRepository, which itself depends on an Entity Framework context:

public class SqlProductRepository : IProductRepository { private readonly CommerceContext context; public SqlProductRepository(CommerceContext context) { this.context = context; } // IProductRepository members go here... }

The CommerceContext class derives from the Entity Framework DbContext class, which, last time I looked, isn't thread-safe. Thus, when used in a web application, it's very important to create a new instance of the CommerceContext class for every request, because otherwise you may experience errors. What's worse is that these errors will be threading errors, so you'll not discover them when you test your web application on your development machine, but when in production, you'll have multiple concurrent requests, and then the application will crash (or perhaps 'just' lose data, which is even worse).

(As a side note I should point out that I've used neither Entity Framework nor the Repository pattern for years now, but the example explains the problem well, in a context familiar to most people.)

The ProductService class is a stateless service, and therefore thread-safe, so it's an excellent candidate for the Singleton lifestyle. However, as it turns out, that's not going to work.

NInject example #

If you want to configure ProductService and its dependencies using Ninject, you might accidentally do something like this:

var container = new StandardKernel(); container.Bind<ProductService>().ToSelf().InSingletonScope(); container.Bind<IProductRepository>().To<SqlProductRepository>();

With Ninject you don't need to register concrete types, so there's no reason to register the CommerceContext class; it wouldn't be necessary to register the ProductService either, if it wasn't for the fact that you'd like it to have the Singleton lifestyle. Ninject's default lifestyle is Transient, so that's the lifestyle of both SqlProductRepository and CommerceContext.

As you've probably already predicted, the Singleton lifestyle of ProductService captures both the direct dependency IProductRepository, and the indirect dependency CommerceContext:

var actual1 = container.Get<ProductService>(); var actual2 = container.Get<ProductService>(); // You'd want this assertion to pass, but it fails Assert.NotEqual(actual1.Repository, actual2.Repository);

The repositories are the same because actual1 and actual2 are the same instance, so naturally, their constituent components are also the same.

This is problematic because CommerceContext (deriving from DbContext) isn't thread-safe, so if you resolve ProductService from multiple concurrent requests (which you could easily do in a web application), you'll have a problem.

The immediate fix is to make this entire sub-graph Transient:

var container = new StandardKernel(); container.Bind<ProductService>().ToSelf().InTransientScope(); container.Bind<IProductRepository>().To<SqlProductRepository>();

Actually, since Transient is the default, stating the lifetime is redundant, and can be omitted:

var container = new StandardKernel(); container.Bind<ProductService>().ToSelf(); container.Bind<IProductRepository>().To<SqlProductRepository>();

Finally, since you don't have to register concrete types with Ninject, you can completely omit the ProductService registration:

var container = new StandardKernel(); container.Bind<IProductRepository>().To<SqlProductRepository>();

This works:

var actual1 = container.Get<ProductService>(); var actual2 = container.Get<ProductService>(); Assert.NotEqual(actual1.Repository, actual2.Repository);

While the Captive Dependency error is intrinsically tied to using a DI Container, it's by no means particular to Ninject.

Autofac example #

It would be unfair to leave you with the impression that this problem is a problem with Ninject; it's not. All DI Containers I know of have this problem. Autofac is just another example.

Again, you'd like ProductService to have the Singleton lifestyle, because it's thread-safe, and it would be more efficient that way:

var builder = new ContainerBuilder(); builder.RegisterType<ProductService>().SingleInstance(); builder.RegisterType<SqlProductRepository>().As<IProductRepository>(); builder.RegisterType<CommerceContext>(); var container = builder.Build();

Like Ninject, the default lifestyle for Autofac is Transient, so you don't have to explicitly configure the lifetimes of SqlProductRepository or CommerceContext. On the other hand, Autofac requires you to register all services in use, even when they're concrete classes; this is the reason you see a registration statement for CommerceContext as well.

The problem is exactly the same as with Ninject:

var actual1 = container.Resolve<ProductService>(); var actual2 = container.Resolve<ProductService>(); // You'd want this assertion to pass, but it fails Assert.NotEqual(actual1.Repository, actual2.Repository);

The reason is the same as before, as is the solution:

var builder = new ContainerBuilder(); builder.RegisterType<ProductService>(); builder.RegisterType<SqlProductRepository>().As<IProductRepository>(); builder.RegisterType<CommerceContext>(); var container = builder.Build(); var actual1 = container.Resolve<ProductService>(); var actual2 = container.Resolve<ProductService>(); Assert.NotEqual(actual1.Repository, actual2.Repository);

Notice that, because the default lifetime is Transient, you don't have to state it while registering any of the services.

Concluding remarks #

You can re-create this problem with any major DI Container. The problem isn't associated with any particular DI Container, but simply the fact that there are trade-offs associated with using a DI Container, and one of the trade-offs is a reduction in compile-time feedback. The way typical DI Container registration APIs work, they can't easily detect this lifetime configuration mismatch.

It's been a while since I last did a full survey of the .NET DI Container landscape, and back then (when I wrote my book), no containers could detect this problem. Since then, I believe Castle Windsor has got some Captive Dependency detection built in, but I admit that I'm not up to speed; other containers may have this feature as well.

When I wrote my book some years ago, I considered including a description of the Captive Dependency configuration error, but for various reasons, it never made it into the book:

- As far as I recall, it was Krzysztof Koźmic who originally made me aware of this problem. In emails, we debated various ideas for a name, but we couldn't really settle on something catchy. Since I don't like to describe something I can't name, it never really made it into the book.

- One of the major goals of the book was to explain DI as a set of principles and patterns decoupled from DI Containers. The Captive Dependency problem is specifically associated with DI Containers, so it didn't really fit into the book.

In a follow-up post to this, I'll demonstrate why you don't have the same problem when you hand-code your object graphs.

Feedback on ASP.NET vNext Dependency Injection

ASP.NET vNext includes a Dependency Injection API. This post offers feedback on the currently available code.

As part of Microsoft's new openness, the ASP.NET team have made the next version of ASP.NET available on GitHub. Obviously, it's not yet done, but I suppose that the reasons for this move is to get early feedback, as well as perhaps take contributions. This is an extremely positive move for the ASP.NET team, and I'm very grateful that they have done this, because it enables me to provide early feedback, and offer my help.

It looks like one of the proposed new features of the next version of ASP.NET is a library or API simply titled Dependency Injection. In this post, I will provide feedback to the team on that particular sub-project, in the form of an open blog post. The contents of this blog post is also cross-posted to the official ASP.NET vNext forum.

Dependency Injection support #

The details on the motivation for the Dependency Injection library are sparse, but I assume that the purpose is provide 'Dependency Injection support' to ASP.NET. If so, that motivation is laudable, because Dependency Injection (DI) is the proper way to write loosely coupled code when using Object-Oriented Design.

Some parts of the ASP.NET family already have DI support; personally, I'm most familiar with ASP.NET MVC and ASP.NET Web API. Other parts have proven rather hostile towards DI - most notably ASP.NET Web Forms. The problem with Web Forms is that Constructor Injection is impossible, because the Web Forms framework doesn't provide a hook for creating new Page objects.

My interpretation #

As far as I can tell, the current ASP.NET Dependency Injection code defines an interface for creating objects:

public interface ITypeActivator { object CreateInstance( IServiceProvider services, Type instanceType, params object[] parameters); }

In addition to this central interface, there are other interfaces that enable you to configure a 'service collection', and then there are Adapters for

- Autofac

- Ninject

- StructureMap

- Unity

- Caste Windsor

My recommendations #

It's an excellent idea to add 'Dependency Injection support' to ASP.NET, for the few places where it's not already present. However, as I've previously explained, a Conforming Container isn't the right solution. The right solution is to put the necessary extensibility points into the framework:

- ASP.NET MVC already has a good extensibility point in the IControllerFactory interface. I recommend keeping this interface, and other interfaces in MVC that play a similar role.

- ASP.NET Web API already has a good extensibility point in the IHttpControllerActivator interface. I recommend keeping this interface, and other interfaces in Web API that play a similar role.

- ASP.NET Web Forms have no extensibility point that enables you to create custom Page objects. I recommend adding an IPageFactory interface, as described in my article about DI-Friendly frameworks. Other object types related to Web Forms, such as Object Data Sources, suffer from the same shortcoming, and should have similar factory interfaces.

- There may be other parts of ASP.NET with which I'm not particularly familiar (SignalR?), but they should all follow the same pattern of defining Abstract Factories for user classes, in the cases where these don't already exist.

"perfection is attained not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing more to remove." - Antoine de Saint ExupéryThese are my general recommendations to the team, but if desired, I'd also like to offer my assistance with any particular issues the team might encounter.

DI-Friendly Framework

How to create a Dependency Injection-friendly software framework.

It seems to me that every time a development organisation wants to add 'Dependency Injection support' to a framework, all too often, the result is a Conforming Container. In this article I wish to describe good alternatives to this anti-pattern.

In a previous article I covered how to design a Dependency Injection-friendly library; in this article, I will deal with frameworks. The distinction I usually make is:

- A Library is a reusable set of types or functions you can use from a wide variety of applications. The application code initiates communication with the library and invokes it.

- A Framework consists of one or more libraries, but the difference is that Inversion of Control applies. The application registers with the framework (often by implementing one or more interfaces), and the framework calls into the application, which may call back into the framework. A framework often exists to address a particular general-purpose Domain (such as web applications, mobile apps, workflows, etc.).

The composition challenge #

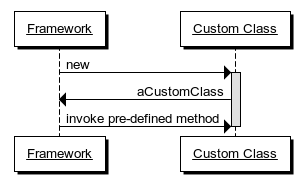

One of the most challenging aspects of writing a framework is that the framework designers can't predict what users will want to do. Often, a framework defines a way for you to interact with it:

- Implement an interface

- Derive from a base class

- Adorn your classes or methods with a particular attribute

- Name your classes according to some naming convention

Once the framework has an instance of the custom user class, it can easily start using it by invoking methods defined by the interface the class implements, etc. The difficult part is creating the instance. By default, most frameworks require that a custom class has a default (parameterless) constructor, but that may be a design smell, and doesn't fit with the Constructor Injection pattern. Such a requirement is a sensible default, but isn't Dependency Injection-friendly; in fact, it's an example of the Constrained Construction anti-pattern, which you can read about in my book.

Most framework designers realize this and resolve to add Dependency Injection support to the framework. Often, in the first few iterations, they get it right!

Abstractions and ownership #

If you examine the sequence diagram above, you should realize one thing: the framework is the client of the custom user code; the custom user code provides the services for the framework. In most cases, the custom user code exposes itself as a service to the framework. Some examples may be in order:

- In ASP.NET MVC, user code implements the IController interface, although this is most commonly done by deriving from the abstract Controller base class.

- In ASP.NET Web API, user code implements the IHttpController interface, although this is most commonly done by deriving from the abstract ApiController class.

- In Windows Presentation Foundation, user code derives from the Window class.

There's an extremely important point hidden here: although it looks like a framework has to deal with the unknown, all the requirements of the framework are known:

- The framework defines the interface or base class

- The framework creates instances of the custom user classes

- The framework invokes methods on the custom user objects

"clients [...] own the abstract interfaces"This is a quote from chapter 11, which is about the Dependency Inversion Principle, so it all fits.

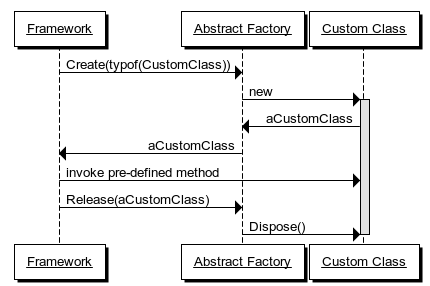

Notice what the framework does in the list above. Not only does it use the custom user objects, it also creates instances of the custom user classes. This is the tricky part, where many framework designers have a hard time seeing past the fact that the custom user code is unknown. However, from the perspective of the framework, the concrete type of a custom user class is irrelevant; it just needs to create an instance of it, but treat it as the well-known interface it implements.

- The client owns the interface

- The framework is the client

- The framework knows what it needs, not what user code needs

- Thus, framework interfaces should be defined by what the framework needs, not as a general-purpose interface to deal with user code

- Users know much better what user code needs than the framework can ever hope to do

public interface IFrameworkControllerFactory { IFrameworkController Create(Type controllerType); }

assuming that the interface that the user code must implement is called IFrameworkController.

The custom user class may contain one or more disposable objects, so in order to prevent resource leaks, the framework must also provide a hook for decommissioning:

public interface IFrameworkControllerFactory { IFrameworkController Create(Type controllerType); void Release(IFrameworkController controller); }

In this expanded iteration of the Abstract Factory, the contract is that the framework will invoke the Release method when it's finished with a particular IFrameworkController instance.

Some framework designers attempt to introduce a 'more sophisticated' lifetime model, but there's no reason for that. This Create/Release design is simple, easy to understand, works very well, and fits perfectly into the Register Resolve Release pattern, since it provides hooks for the Resolve and Release phases.

ASP.NET MVC 1 and 2 provided flawless examples of such Abstract Factories in the form of the IControllerFactory interface:

public interface IControllerFactory { IController CreateController( RequestContext requestContext, string controllerName); void ReleaseController(IController controller); }

Unfortunately, in ASP.NET MVC 3, a completely unrelated third method was added to that interface; it's still useful, but not as clean as before.

Framework designers ought to stop here. With such an Abstract Factory, they have perfect Dependency Injection support. If a user wants to hand-code the composition, he or she can implement the Abstract Factory interface. Here's an ASP.NET 1 example:

public class PoorMansCompositionRoot : DefaultControllerFactory { private readonly Dictionary<IController, IEnumerable<IDisposable>> disposables; private readonly object syncRoot; public PoorMansCompositionRoot() { this.syncRoot = new object(); this.disposables = new Dictionary<IController, IEnumerable<IDisposable>>(); } protected override IController GetControllerInstance( RequestContext requestContext, Type controllerType) { if (controllerType == typeof(HomeController)) { var connStr = ConfigurationManager .ConnectionStrings["postings"].ConnectionString; var ctx = new PostingContext(connStr); var sqlChannel = new SqlPostingChannel(ctx); var sqlReader = new SqlPostingReader(ctx); var validator = new DefaultPostingValidator(); var validatingChannel = new ValidatingPostingChannel( validator, sqlChannel); var controller = new HomeController(sqlReader, validatingChannel); lock (this.syncRoot) { this.disposables.Add(controller, new IDisposable[] { sqlChannel, sqlReader }); } return controller; } return base.GetControllerInstance(requestContext, controllerType); } public override void ReleaseController(IController controller) { lock (this.syncRoot) { foreach (var d in this.disposables[controller]) { d.Dispose(); } } } }

In this example, I derive from DefaultControllerFactory, which implements the IControllerFactory interface - it's a little bit easier than implementing the interface directly.

In this example, the Composition Root only handles a single user Controller type (HomeController), but I'm sure you can extrapolate from the example.

If a developer rather prefers using a DI Container, that's also perfectly possible with the Abstract Factory approach. Here's another ASP.NET 1 example, this time with Castle Windsor:

public class WindsorCompositionRoot : DefaultControllerFactory { private readonly IWindsorContainer container; public WindsorCompositionRoot(IWindsorContainer container) { if (container == null) { throw new ArgumentNullException("container"); } this.container = container; } protected override IController GetControllerInstance( RequestContext requestContext, Type controllerType) { return (IController)this.container.Resolve(controllerType); } public override void ReleaseController(IController controller) { this.container.Release(controller); } }

Notice how seamless the framework's Dependency Injection support is: the framework has no knowledge of Castle Windsor, and Castle Windsor has no knowledge of the framework. The small WindsorCompositionRoot class acts as an Adapter between the two.

Resist the urge to generalize #

If frameworks would only come with the appropriate hooks in the form of Abstract Factories with Release methods, they'd be perfect.

Unfortunately, as a framework becomes successful and grows, more and more types are added to it. Not only (say) Controllers, but Filters, Formatters, Handlers, and whatnot. A hypothetical XYZ framework would have to define Abstract Factories for each of these extensibility points:

public interface IXyzControllerFactory { IXyzController Create(Type controllerType); void Release(IXyzController controller); } public interface IXyzFilterFactory { IXyzFilter Create(Type fiterType); void Release(IXyzFilter filter); } // etc.

Clearly, that seems repetitive, so it's no wonder that framework designers look at that repetition and wonder if they can generalize. The appropriate responses to this urge, are, in prioritised order:

- Resist the urge to generalise, and define each Abstract Factory as a separate interface. That design is easy to understand, and users can implement as many or as few of these Abstract Factories as they want. In the end, frameworks are designed for the framework users, not for the framework developers.

- If absolutely unavoidable, define a generic Abstract Factory.

Many distinct, but similar Abstract Factory interfaces may be repetitive, but that's unlikely to hurt the user. A good framework provides optional extensibility points - it doesn't force users to relate to all of them at once. As an example, I'm a fairly satisfied user of the ASP.NET Web API, but while I create lots of Controllers, and the occasional Exception Filter, I've yet to write my first custom Formatter. I only add a custom IHttpControllerActivator for my Controllers. Although (unfortunately) ASP.NET Web API has had a Conforming Container in the form of the IDependencyResolver interface since version 1, I've never used it. In a properly designed framework, a Conforming Container is utterly redundant.

If the framework must address the apparent DRY violation of multiple similar Abstract Factory definitions, an acceptable solution is a generic interface:

public interface IFactory<T> { T Create(Type itemType); void Release(T item); }

This type of generic Factory is generally benign, although it may hurt discoverability, because a generic type looks as though you can use anything for the type argument T, where, in fact, the framework only needs a finite set of Abstract Factories, like

- IFactory<IXyzController>

- IFactory<IXyzFilter>

- IFactory<IXyzFormatter>

- IFactory<IXyzHandler>

In the end, though, users will need to inform the framework about their custom factories, so this discoverability issue can be addressed. A framework usually defines an extensibility point where users can tell it about their custom extensions. An example of that is ASP.NET MVC's ControllerBuilder class. Although I'm not too happy about the use of a Singleton, it's hard to do something wrong:

var controllerFactory = new PoorMansCompositionRoot(); ControllerBuilder.Current.SetControllerFactory(controllerFactory);

Unfortunately, some frameworks attempt to generalize this extensibility point. As an example, in ASP.NET Web API, you'll have to use ServicesContainer.Replace:

public void Replace(Type serviceType, object service)

Although it's easy enough to use:

configuration.Services.Replace( typeof(IHttpControllerActivator), new CompositionRoot(this.eventStore, this.eventStream, this.imageStore));

It's not particularly discoverable, because you'll have to resort to the documentation, or trawl through the (fortunately open source) code base, in order to discover that there's an IHttpControllerActivator interface you'd like to replace. The Replace method gives the impression that you can replace any Type, but in practice, it only makes sense to replace a few well-known interfaces, like IHttpControllerActivator.

Even with a generic Abstract Factory, a much more discoverable option would be to expose all extensible services as strongly-typed members of a configuration object. As an example, the hypothetical XYZ framework could define its configuration API like this:

public class XyzConfiguration { public IFactory<IXyzController> ControllerFactory { get; set; } public IFactory<IXyzFilter> FilterFactory { get; set; } // etc. }

Such use of Property Injection enables users to override only those Abstract Factories they care about, and leave the rest at their defaults. Additionally, it's easy to enumerate all extensibility options, because the XyzConfiguration class provides a one-stop place for all extensibility points in the framework.

Define attributes without behaviour #

Some frameworks provide extensibility points in the form of attributes. ASP.NET MVC, for example, defines various Filter attributes, such as [Authorize], [HandleError], [OutputCache], etc. Some of these attributes contain behaviour, because they implement interfaces such as IAuthorizationFilter, IExceptionFilter, and so on.

Attributes with behaviour is a bad idea. Due to compiler limitations (at least in both C# and F#), you can only provide constants and literals to an attribute. That effectively rules out Dependency Injection, but if an attribute contains behaviour, it's guaranteed that some user comes by and wants to add some custom behaviour in an attribute. The only way to add 'Dependency Injection support' to attributes is through a static Service Locator - an exceptionally toxic design. Attribute designers should avoid this. This is not Dependency Injection support; it's Service Locator support. There's no reason to bake in Service Locator support in a framework. People who deliberately want to hurt themselves can always add a static Service Locator by themselves.

Instead, attributes should be designed without behaviour. Instead of putting the behaviour in the attribute itself, a custom attribute should only provide metadata - after all, that's the original raison d'être of attributes.

Attributes with metadata can then be detected and handled by normal services, which enable normal Dependency Injection. See this Stack Overflow answer for an ASP.NET MVC example, or my article on Passive Attributes for a Web API example.

Summary #

A framework must expose appropriate extensibility points in order to be useful. The best way to support Dependency Injection is to provide an Abstract Factory with a corresponding Release method for each custom type users are expected to create. This is the simplest solution. It's extremely versatile. It has few moving parts. It's easy to understand. It enables gradual customisation.

Framework users who don't care about Dependency Injection at all can simply ignore the whole issue and use the framework with its default services. Framework users who prefer to hand-code object composition, can implement the appropriate Abstract Factories by writing custom code. Framework users who prefer to use their DI Container of choice can implement the appropriate Abstract Factories as Adapters over the container.

That's all. There's no reason to make it more complicated than that. There's particularly no reason to force a Conforming Container upon the users.

Comments

1. A framework generally must have some sort of initializer, particularly if it must do something like add route values to MVC (which must be done during a particular point in the application lifecycle). This startup code must be placed in the composition root of the application. Considering that the framework should have no knowledge of the composition root of the application, how best can this requirement be met? The only thing I have come up with is to add a static method that must be in the application startup code and using WebActivator to get it running.

2. Sort of related to the first issue, how would it be possible to address the extension point where abstract factories can be injected without providing a static method? I am considering expanding the static method from #1 to include an overload that accepts an Action<IConfiguration> as a parameter. The developer can then use that overload to create a method Configure(IConfiguration configuration) in their application to set the various abstract factory (in the IConfiguration instance, of course). The IConfiguration interface would contain well named members to set specific factories, so it is easy to discover what factory types can be provided. Could this idea be improved upon?

3. Considering that my framework relies on the .NET garbage collector to dispose of objects that were created by a given abstract factory, what pattern can I adapt to ensure the framework always calls Release() at the right time? A concrete example would seem to be in order.

Shad, thank you for writing. From your questions it's a bit unclear to me whether you're writing a framework or a library. Although you write framework, your questions sound like it's a library... or at least, if you're writing a framework, it sounds like you're writing a sub-framework for another framework (MVC). Is that correct?

Re: 1. It's true that a framework needs some sort of initializer. In the ideal world, it would look something like new MyFrameworkRunner().Run();, and you would put this single line of code in the entry point of your application (its Main method). Unfortunately, ASP.NET doesn't work that way, so we have to work with the cards we're dealt. Here, the entry point is Application_Start, so if you need to initialise something, this is where you do it.

The initialisation method can be a static or instance method.

Re: 2. That sounds reasonable, but it depends upon where your framework stores the custom configuration. If you add a method overload to a static method, it almost indicates to me that the framework's configuration is stored in shared state, which is never attractive. An alternative is to utilise the Dependency Inversion Principle, and instead inject any custom configuration into the root of the framework itself: new MyFrameworkRunner(someCustomCoonfiguration).Run();

Re: 3. A framework is responsible for the lifetime of the objects it creates. If it creates objects, it must also provide an extensibility point for decommissioning them after use. This is the reason I strongly recommend (in this very article) that an Abstract Factory for a framework must always have a Release method in addition to the Create method.

A concrete example is difficult to provide when the question is abstract...

If you want to take a look, the framework I am referring to is called MvcSiteMapProvider. I would definitely categorize it as a sub-framework of MVC because it can rely on the host application to provide service instances (although it doesn't have to). It has a static entry point to launch it's composition root (primarily because WebActivator requires there to be a static method, and WebActivator can launch the application without the need for the NuGet package to modify the Global.asax file directly), but the inner workings rely (almost) entirely on instances and constructor injection. There is still some refactoring to be done on the HTML helpers to put all of the logic into replaceable instances, which I plan to do in a future major version.

Since it is about 90% of the way there already, my plan is to modify the internal poor-man's DI container to accept injected factory instances to provide the alternate implementations. A set of default factories will be created during initialization, and then it will pass these instances (through the IConfiguration variable) out to the host application where it can replace or wrap the factories. After the host does what it needs to, the services will be wired up in the poor man's DI container and then its off to the races. I think this can be done without dropping support for the existing Conforming Container, meaning I don't need to wait for a major release to implement it.

Anyway, you have adequately answered my 2 questions about initialization and I think I am now on the right track. You also gave me some food for thought as how to accomplish this without making it static (although ultimately some wrapper method will need to be static in order to make it work with WebActivator).

As for my 3rd question, you didn't provide a sufficient answer. However, I took a peek at the MVC source code to see how the default IControllerFactory ReleaseController() method was implemented, and it is similar to your PoorMansCompositionRoot example above (sort of). They just check to see if IController will cast to IDisposable and call Dispose() if it does. I guess that was the general pattern I was asking for, and from your example it looks like you are in agreement with Microsoft on the approach.

Shad, I don't exactly recall how DefaultControllerFactory.ReleaseController is implemented, but in general, only type-checking for IDisposable and calling Dispose may be too simplistic a view to take in the general case. As I explain in chapter 8 in my book, releasing an object graph isn't always equivalent to disposal. In the general case, you also need to take into account the extra dimension of the various lifetimes of objects in an object graph. Some object may have a longer lifetime scope, so even when you invoke Release on them, their time isn't up yet, and therefore it would be a bug to dispose of them.

This is one of the reasons a properly design Abstract Factory interface (for use with .NET) must have a Release method paired with its Create method. Only the factory knows if it actually created an object (as opposed to reused an existing object), so only the factory knows when it's appropriate to dispose of it again.

Dear Mark,

Concering the the type of generic IFactory, I think that aplying a Marker Interface for T whould make the implementation very discoverable and also type-safe.

What is your opinion about it?

Robert, thank you for writing. What advantage would a Marker Interface provide?

1. From framework perspective - less code. 2. From client perspective - more consistent API. We can see all the possible hooks just by investigating which interfaces of the Framwork implements the marker interface - even the IntelliSence would show the possibilities of the factories which can be implemented. As I write the comment, I see also some drawbacks - the IFactory should generally not work with generic which is the marker interface itself and also for some client interfaces that would implement the marker interface. However still I find it much better ans safer than just having a generic IFactory without ANY constraints.

Additionally maybe you could also enchance this post with information how to Bootstrap the framwork? For example I extremely like thecodejunkie's way which he presented on his Guerilla Framework Design presentation.

Or also maybe you could give some examples how could the framework developers use the container? Personally the only way I see that it could be done is to use some "embedded" container like TinyIoC. This is the way how Nancy is done.

How does a Marker Interface lead to less framework code? It has no behaviour, so it's hard for me to imagine how it leads to less code. From a client perspective, it also sounds rather redundant to me. How can we see the possible hooks in the framework by looking for a Marker Interface? Aren't all public interfaces defined by a framework hooks?

What do you mean: "how could the framework developers use the container"? Which container? The whole point of this very post is to explain to programmers how to design a DI Friendly framework without relying on a container - any container.

Hi Mark, thank you for this very helpful blog post. I still have two questions though:

- To create the default implementations (that are provided with the framework) of the factories exposed in XyzConfiguration, it might be necessary to compose a complex dependency graph first, because the the default implementations of the factories themselves have dependencies. So there must be code in the framework that does this composition. At the same time this composition code should be extensible and it should be possible let the DI container of the customers choice to this composition. Can you sektch out how one would design for such a scenario or are you aware of a framework that does this well?

- Once the factories in XyzConfiguration are configured and initialized, it seems that all framework classes that need one of those factories get a dependency on the XyzConfiguration, because that's the place where to get the factories from. This would be Service Locator antipattern how would I avoid this?

bitbonk, thank you for writing.

Re 1: A framework can compose any default complex object graph it wants to. If a framework developer is worried about performance, he or she can always make the default configuration a lazily initialized Singleton:

public class XyzConfiguration { public IFactory<IXyzController> ControllerFactory { get; set; } public IFactory<IXyzFilter> FilterFactory { get; set; } // etc. private static readonly Lazy<XyzConfiguration> defaultConfiguration = new Lazy<XyzConfiguration>(() => new XyzConfiguration { ControllerFactory = new XyzControllerFactory( new Foo( new Bar( new Baz(/* Etc. */)))), // Assign FilterFactory in the same manner }); public static XyzConfiguration Default { get { return defaultConfiguration.Value; } } }

Since the default value is only initialized if it's used, there's no cost associated with it. The XyzConfiguration class still has a public constructor, so if a framework user doesn't want to use the default, he or she can always create a new instance of the class, and pass that configuration to the framework when it's bootstrapping. The user can even use XyzConfiguration.Default as a starting point, and only tweak the properties he or she wants to tweak.

While XyzConfiguration.Default defines default graphs, all the constituent elements (XyzControllerFactory, Foo, Bar, Baz, etc.) are public classes with public constructors, so a framework user can always duplicate the graph him- or herself. If the framework developers want to make it easier to tweak the default graph, they can supply a facade using one of the options outlines in my companion article about DI-friendly libraries.

Re 2: Such an XyzConfiguration class isn't a Service Locator. It's a concrete, well-known, finite collection of Abstract Factories, whereas a Service Locator is an unknown, infinite set of Abstract Factories.

Still, I would recommend that framework developers adhere to the Interface Segregation Principle and only take dependencies on those Abstract Factories they need. If a framework feature needs an IFactory<IXyzController>, then that's what it should take in via its constructor. The framework should pass to that constructor configuration.ControllerFactory instead of the entire configuration object.

Thanks Mark for your answer, it all makes sense to me but my first question was more geared towards the DI container. For the composition of the default dependency graphs, the (my) framework needs to provide three things at the same time:

- Means that helps the user build default combination(s) of dependencies for common scenarios without forcing the user to use (or depend on) any DI container. I can see how this can easily be achieved by using the factory approach you mentioned or by using facade or constructor chaining as you mentioned and in your companion article about DI-friendly libraries

- Means that helps the user build the default combination(s) of dependencies for common scenarios using the DI container of the user's choice (i.e. an existing container instance that was already created and is used for the rest of the application dependencies too). The user might want to do this because she wants to resolve some the dependencies that have been registered by the framework using the DI container of her application. I can see how this could be achieved by introducing some sort of framework-specific DI container abstraction and provide implementations for common containers (like XyzFramework.Bootstrappers.StructureMap or XyzFramework.Bootstrappers.SimpleInjector ...). It looks like this is how it is done in NancyFx.

- Means that helps the user modify and adapt the default combination(s) of dependencies for common scenarios using that DI container. The user might want to modify just parts of a default dependency graph or wants to intercept just some of the default dependencies. The user should be able to do this without having to reimplement the whole construction logic. Again NancyFx seems to do this by introducing a DI container abstraction.

I find it particularly challenging to come up with a good design that meets all three of these requirements. I don't really have a question for you here, because the answer will most likely have to be: "it depends". But feel free to comment, if you have any additional thoughts that are worth sharing.

Before we continue this discussion, I find myself obliged to point out that you ought have a compelling reason to create a framework. Tomas Petricek has a great article that explains why you should favour libraries over frameworks. The article uses F# for code examples, but the arguments apply equally to C# and Object-Oriented Design.

I have a hard time coming up with a single use case where a framework would be the correct design decision, but perhaps your use case is a genuine case for making a framework...

That said, I don't understand your second bullet point. If all the classes involved in building those default object graphs are public, a user can always register them with their DI Container of choice. Why would you need a container abstraction (which is a poor idea) for that?

The third bullet point makes me uneasy as well. It seems to me that the entire premise in this, and your previous, comment is that the default object graphs are deep and complex. Is that really necessary?

Still, if you want to make it easy for a user to modify the default factories, you can supply a Facade or Fluent Builder as already outlined. The user can use that API to tweak the defaults. Why would the user even wish to involve a DI Container in that process?

For the sake of argument, let's assume that this is somehow necessary. The user can still hook into the provided API and combine that with a DI Container. Here's a Castle Windsor example:

container.Register(Component .For<IFactory<IXyzController>>() .UsingFactoryMethod(k => k .Resolve<XyzControllerFactoryBuilder>() .WithBar(k.Resolve<IBar>()) .Build()));

This utilises the API provided by the framework, but still enables you to resolve a custom IBar instance with the DI Container. All other objects built by XyzControllerFactoryBuilder are still handled by that Fluent Builder.

I like to respond to bitbonk's comment where he states that "this could be achieved by introducing some sort of framework-specific DI container abstraction" where he mentions that NancyFx takes this approach.

It is important to note that NancyFx does not contain an adapter for Simple Injector and it has proven to be impossible to create an adapter for NancyFx's Conforming Container. The Conforming Container always expects certain behavior of the underlying container, and there will always be at least one container that fails to comply to this contract. In the case of NancyFx, it is Simple Injector. This is proof that the Conforming Container is an anti-pattern.

Besides the Conforming Container design, Nancy does however contain the right abstractions to intercept the creation of Nancy's root types (modules). This has actually made it very straightforward to plugin Simple Injector into NancyFx. It's just a matter of implementing a custom INancyModuleCatalog and optionally an INancyContextFactory.

Although we might think that the Conforming Container and having proper abstractions can live side-by-side, there is a serious downside. In the case of NancyFx for instance, the designers were so focussed on their Conforming Container design, that they had a hard time imagining that anyone would want to do without it. This lead to the situation that they themselves didn't even realize that a container could actually be plugged-in without the use of the Conforming Container. This caused me figure this out by myself.

So the risk is that the focus on the Conforming Container causes the designers of the framework to forget about developers that can't comply with their Conforming Container abstraction. This makes working without such adapter an afterthought to the designers. We are seeing this exact thing happening within Microsoft with their new .NET Core framework. Although at the moment of writting (which is 6 months after .NET Core has been released) only one of the leading DI containers has official support for the .NET Core Conforming Container, Microsoft makes little efforts in trying to improve the situation for the rest of the world, because, as the lead architect behind their Conforming Container quite accurately described it himself: "it's just my bias towards conforming containers clouding my vision".

Dear Mark, all,

I would appreciate some advice. Thanks in advance.

I am refactoring a small real-time graphics framework, and am unsure the best way to structure the code at the top level.

I doubt I have described things very well, but fingers crossed...

I provide a bit of background on how I got to this point, but ultimately my question is one about where exact a framework's own internal wiring happens, particularly the registering or creation of internal components that the USER should not have knowledge of.

Framework or Library?:

The first advice I read was actually to avoid using a FRAMEWORK structure where possible. However, although it is not of sufficient breadth to describe my code as an "Engine", it needs to control the looping of the application (and entire lifetime). I do NOT deem it realistic to refactor into a LIBRARY. I particularly do not believe the "solution" to structuring the update() part of a game engine, as described here, is simple to use or elegant.

Article Advocating Libraries over Frameworks

Therefore, I decided to stick with the FRAMEWORK approach.

Framework Aims:

The Framework Accepts (or will Create, as per your recommendation) an object implementating IApplication

The Framework calls methods in IApplication such as Load(), Update(), Draw()

The Framework provides Functions to the Application via a number of interfaces: IGraphics, IInput etc

The Framework should follow DI principles to ease Testing

The USER should NOT be required to wire-up the internal components of the framework.

The API / Interface usage be simple for the USER: i.e. Framework.Run(Application);

The API should be clean - i.e. I would prefer if the USER were unable to see / instantiate internal framework objects (i.e. preference is for INTERNAL rather than PUBLIC preference)

I would like to use an IOC container

My Initial Approach:

My approach before finding this article was therefore to have something like:

Assembly0: Application

Assembly1: Contains Interfaces, & Framework incl. a Static Loader Method

Assembly2: Framework Tests

The application would create IApplication interface, and feed it via the Static Loader Method into Assembly1

In Assembly1 (the framework), there would be a framework composition root that would spool up the engine, either by using an IOC container and registering components, or manual DI

Problems Encountered First, in relation to testing (how I got to the issue, rather than the issuer itself):

It was at this point, whilst trying to ensure the API was clean, that I realised I was unable to use INTERNAL only classes and still test them without add "Internals Visible Attribute". This felt a bit dirty (BUT might be the right solution). I thought I could pull out the interface to another third assembly, but given the references needed i always ended up being visible to the user. Anyway, that's besides the point slightly...

It was at this point I started to look for some advice on how to structure a framework, and I ran across this article...

So it became clear that I should make the Framework Create the Application via a Factory... which OK is fine

but i get stuck when trying to figure out how to adhere too

- DI containers / composition roots should only exist in the application. There should only be one container / composition root. It should not live in the framework

Where i am now stuck:

I don't have any clue how the approach presented in your article solves the internal setup and wiring of the framework itself?

I do not see how I can rely on the FRAMEWORK USER to choose either simple DI or using an IOC container, without them needing to know how to wire up different components inside my framework. This does NOT seem EASY to me. Should the user really have to register things like the Graphics Implementation against the IGraphics interface, etc?

Is it really that bad to use two IOCs? One only internal to the framework itself, used in a static set up method? Am I missing something obvious about how I should structure my code?

It seems one option (at least on the Library-form side) is to use a facade that offers default wiring options. I assume this sits in the framework assembly, containers a factory method, and is OK to use a DI container within? I am then unsure exactly how that would pair with the abstract factories in this advice that create the applications.

Perhaps there is a good example of a framework (or trivial example) that can be pointed too?

Thanks again. I assume there is no perfect solution but appreciate your advice.

Dear Mark,

My apologies for the somewhat rambled query above.

I believe it might be more simple if I show you my simplified version of a proposed structure for a framework, that takes a user defined application.

Repo With Simple Framework Example

The Assemblies involved are (named more simply in the repo):

UserApplication

ApiInterface

Framework

FrameworkTesting

I would be very interested to know if you see this framework structure as misguided or plain smelly.

I am finding this topic quite interesting, and would be facinated to see an improved approach.

If it turns out not to stink too badly, I will press on and use this structure

I have read your DI book (potentially missing some key points given I am asking these questions...), and so would really appreciate and respect your opinion.

This structure features:

- A user created application object inheriting the application interface

- A static method in a Facade class to help wire up the framework (is a static compoisiton route that could include an IoC container)

- Allows application -side composition root by user NOT using the Facade helper

- A somewhat 'clean' public interface / API whereby internal framework components are atleast deeper in the namespace tree

- Full testability of internal components and external services

- Constructor injection to achieve DI

How this structure breaks advice:

- Using the Helper Facade could result in any IoC container not being in only composition route (and perhaps the application employs another container)

- The Framework does not instantiate the Custom Application Objects

For the latter, I am unsure how to create something Framework Side that is a factory to create a custom user class without referencing the application namespace and adding bi-drectional dependency on App -> Framework

I am sure I am missing some obvious stuff.

Thanks again

John

John, thank you for writing. When I look at your GitHub repository, I think that it looks fine. I particularly like that if I had to work with something like this, I get to control the lifetime of all my object graphs. I just have to implement IApp and call CompositionFacade.Run with it.

This makes it more like a library than a framework, although I do understand that the intent is that Run executes for the lifetime of the application.

This means that if I need to implement IApp with a complex graph of objects, I can do that. In my Main method, I can compose my object graph with Pure DI, or I can leverage a DI Container if I so choose.

What happens inside of CompositionFacade.Run is completely opaque to me, which implies good encapsulation.

I do, however, consider a separate interface library redundant. What purpose does it serve?

DI-Friendly Library

How to create a Dependency Injection-friendly software library.

In my book, I go to great lengths to explain how to develop loosely coupled applications using various Dependency Injection (DI) patterns, including the Composition Root pattern. With the great emphasis on applications, I didn't particularly go into details about making DI-friendly libraries. Partly this was because I didn't think it was necessary, but since one of my highest voted Stack Overflow answers deal with this question, it may be worth expanding on.

In this article, I will cover libraries, and in a later article I will deal with frameworks. The distinction I usually make is:

- A Library is a reusable set of types or functions you can use from a wide variety of applications. The application code initiates communication with the library and invokes it.

- A Framework consists of one or more libraries, but the difference is that Inversion of Control applies. The application registers with the framework (often by implementing one or more interfaces), and the framework calls into the application, which may call back into the framework. A framework often exists to address a particular general-purpose Domain (such as web applications, mobile apps, workflows, etc.).

Most well-designed libraries are already DI-friendly - particularly if they follow the SOLID principles, because the Dependency Inversion Principle (the D in SOLID) is the guiding principle behind DI.

Still, it may be valuable to distil a few recommendations.

Program to an interface, not an implementation #

If your library consists of several collaborating classes, define proper interfaces between these collaborators. This enables clients to redefine part of your library's behaviour, or to slide cross-cutting concerns in between two collaborators, using a Decorator.

Be sure to define these interfaces as Role Interfaces.

An example of a small library that follows this principle is Hyprlinkr, which defines two interfaces used by the main RouteLinker class:

public interface IRouteValuesQuery { IDictionary<string, object> GetRouteValues( MethodCallExpression methodCallExpression); }

and

public interface IRouteDispatcher { Rouple Dispatch( MethodCallExpression method, IDictionary<string, object> routeValues); }

This not only makes it easier to develop and maintain the library itself, but also makes it more flexible for users.

Use Constructor Injection #

Favour the Constructor Injection pattern over other injection patterns, because of its simplicity and degree of encapsulation.

As an example, Hyprlinkr's main class, RouteLinker, has this primary constructor:

private readonly HttpRequestMessage request; private readonly IRouteValuesQuery valuesQuery; private readonly IRouteDispatcher dispatcher; public RouteLinker( HttpRequestMessage request, IRouteValuesQuery routeValuesQuery, IRouteDispatcher dispatcher) { if (request == null) throw new ArgumentNullException("request"); if (routeValuesQuery == null) throw new ArgumentNullException("routeValuesQuery"); if (dispatcher == null) throw new ArgumentNullException("dispatcher"); this.request = request; this.valuesQuery = routeValuesQuery; this.dispatcher = dispatcher; }

Notice that it follows Nikola Malovic's 4th law of IoC that Injection Constructors should be simple.

Although not strictly required in order to make a library DI-friendly, expose every injected dependency as an Inspection Property - it will make the library easier to use when composed in one place, but used in another place. Again, Hyprlinkr does that:

public IRouteValuesQuery RouteValuesQuery { get { return this.valuesQuery; } }

and so on for its other dependencies, too.

Consider an Abstract Factory for short-lived objects #

Sometimes, your library must create short-lived objects in order to do its work. Other times, the library can only create a required object at run-time, because only at run-time is all required information available. You can use an Abstract Factory for that.

The Abstract Factory doesn't always have to be named XyzFactory; in fact, Hyprlinkr's IRouteDispatcher interface is an Abstract Factory, although it's in disguise because it has a different name.

public interface IRouteDispatcher { Rouple Dispatch( MethodCallExpression method, IDictionary<string, object> routeValues); }

Notice that the return value of an Abstract Factory doesn't have to be another interface instance; in this case, it's an instance of the concrete class Rouple, which is a data structure without behaviour.

Consider a Facade #

If some objects are difficult to construct, because their classes have complex constructors, consider supplying a Facade with a good default combination of appropriate dependencies. Often, a simple alternative to a Facade is Constructor Chaining:

public RouteLinker(HttpRequestMessage request) : this(request, new DefaultRouteDispatcher()) { } public RouteLinker(HttpRequestMessage request, IRouteValuesQuery routeValuesQuery) : this(request, routeValuesQuery, new DefaultRouteDispatcher()) { } public RouteLinker(HttpRequestMessage request, IRouteDispatcher dispatcher) : this(request, new ScalarRouteValuesQuery(), dispatcher) { } public RouteLinker( HttpRequestMessage request, IRouteValuesQuery routeValuesQuery, IRouteDispatcher dispatcher) { if (request == null) throw new ArgumentNullException("request"); if (routeValuesQuery == null) throw new ArgumentNullException("routeValuesQuery"); if (dispatcher == null) throw new ArgumentNullException("dispatcher"); this.request = request; this.valuesQuery = routeValuesQuery; this.dispatcher = dispatcher; }

Notice how the Routelinker class provides appropriate default values for those dependencies it can.

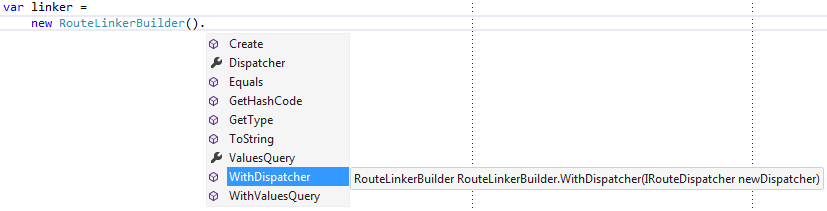

However, a Library with a more complicated API could potentially benefit from a proper Facade. One way to make the API's extensibility points discoverable is by implementing the Facade as a Fluent Builder. The following RouteLinkerBuilder isn't part of Hyprlinkr, because I consider the Constructor Chaining alternative simpler, but it could look like this:

public class RouteLinkerBuilder { private readonly IRouteValuesQuery valuesQuery; private readonly IRouteDispatcher dispatcher; public RouteLinkerBuilder() : this(new ScalarRouteValuesQuery(), new DefaultRouteDispatcher()) { } private RouteLinkerBuilder( IRouteValuesQuery valuesQuery, IRouteDispatcher dispatcher) { this.valuesQuery = valuesQuery; this.dispatcher = dispatcher; } public RouteLinkerBuilder WithValuesQuery(IRouteValuesQuery newValuesQuery) { return new RouteLinkerBuilder(newValuesQuery, this.dispatcher); } public RouteLinkerBuilder WithDispatcher(IRouteDispatcher newDispatcher) { return new RouteLinkerBuilder(this.valuesQuery, newDispatcher); } public RouteLinker Create(HttpRequestMessage request) { return new RouteLinker(request, this.valuesQuery, this.dispatcher); } public IRouteValuesQuery ValuesQuery { get { return this.valuesQuery; } } public IRouteDispatcher Dispatcher { get { return this.dispatcher; } } }

This has the advantage that it's easy to get started with the library:

var linker = new RouteLinkerBuilder().Create(request);

This API is also discoverable, because Intellisense helps users discover how to deviate from the default values:

It enables users to override only those values they care about:

var linker = new RouteLinkerBuilder().WithDispatcher(customDispatcher).Create(request);

If I had wanted to force users of Hyprlinkr to use the (hypothetical) RouteLinkerBuilder, I could make the RouteLinker constructor internal, but I don't much care for that option; I prefer to empower my users, not constrain them.

Composition #

Any application that uses your library can compose objects from it in its Composition Root. Here's a hand-coded example from one of Grean's code bases:

private static RouteLinker CreateDefaultRouteLinker(HttpRequestMessage request) { return new RouteLinker( request, new ModelFilterRouteDispatcher( new DefaultRouteDispatcher() ) ); }

This example is just a small helper method in the Composition Root, but as you can see, it composes a RouteLinker instance using our custom ModelFilterRouteDispatcher class as a Decorator for Hyprlinkr's built-in DefaultRouteDispatcher.

However, it would also be easy to configure a DI Container to do this instead.

Summary #

If you follow SOLID, and normal rules for encapsulation, your library is likely to be DI-friendly. No special infrastructure is required to add 'DI support' to a library.

Comments

I found great library for in process messaging made by Jimmy Bogard - MediatR, but it uses service locator. Implemented mediator uses service locator to lookup for handlers matching message type registered in container. Source.

What would be best approach to eliminate service locator in this case? Would it be better to pass all handler instances in mediator constructor and then lookup for matching one?

Maris, thank you for writing. Hopefully, this article answers your question.

Conforming Container

A Dependency Injection anti-pattern.

Once in a while, someone comes up with the idea that it would be great to introduce a common abstraction over various DI Containers in .NET. My guess is that part of the reason for this is that there are so many DI Containers to choose from on .NET:

- Autofac

- Castle Windsor

- Managed Extensibility Framework

- Ninject

- Simple Injector

- Spring.NET

- StructureMap

- Unity

General form #

At its core, a Conforming Container introduces a central interface, often called IContainer, IServiceLocator, IServiceProvider, ITypeActivator, IServiceFactory, or something in that vein. The interface defines one or more methods called Resolve, Create, GetInstance, or similar:

public interface IContainer { object Resolve(Type type); object Resolve(Type type, params object[] arguments); T Resolve<T>(); T Resolve<T>(params object[] arguments); IEnumerable<T> ResolveAll<T>(); // etc. }

Sometimes, the interface defines only a single of those methods; sometimes, it defines even more variations of methods to create objects based on a Type.

Some Conforming Containers stop at this point, so that the interface only exposes Queries, which means that they only cover the Resolve phase of the Register Resolve Release pattern. Other efforts attempt to address Register phase too:

public interface IContainer { void AddService(Type serviceType, Type implementationType); void AddService<TService, TImplementation>(); // etc. }

The intent is to enable configuration of the container using some sort of metadata. Sometimes, the methods have more advanced configuration parameters that also enable you to specify the lifestyle of the service, etc.

Finally, a part of a typical Conforming Container ecosystem is various published Adapters to concrete DI Containers. A hypothetical Confainer project may publish the following Adapter packages:

- Confainer.Autofac

- Confainer.Windsor

- Confainer.Ninject

- Confainer.Unity

Symptoms and consequences #

A Conforming Container is an anti-pattern, because it's

a commonly occurring solution to a problem that generates decidedly negative consequences,such as:

- Calls to the Conforming Container are likely to be sprinkled liberally over an entire code base.

- It pushes novice users towards the Service Locator anti-pattern. Most people encountering Dependency Injection for the first time mistake it for the Service Locator anti-pattern, despite the entirely opposite natures of these two approaches to loose coupling.

- It attempts to relieve symptoms of bad design, instead of addressing the underlying problem. Too many 'loosely coupled' designs attempt to rely on the Service Locator anti-pattern, which, by default, introduces a dependency to a concrete Service Locator throughout a code base. However, exclusively using the Constructor Injection and Composition Root design patterns eliminate the problem altogether, resulting in a simpler design with fewer moving parts.

- It pulls in the direction of the lowest common denominator.

- It stifles innovation, because new, creative, but radical ideas may not fit into the narrow view of the world a Conforming Container defines.

- It makes it more difficult to avoid using a DI Container. A DI Container can be useful in certain scenarios, but often, hand-coded composition is better than using a DI Container. However, if a library or framework depends on a Conforming Container, it may be difficult to harvest the benefits of hand-coded composition.

- It may introduce versioning hell. Imagine that you need to use a library that depends on Confainer 1.3.7 in an application that also uses a framework that depends on Confainer 2.1.7. Since a Conforming Container is intended as an infrastructure component, this is likely to happen, and to cause much grief.

- A Conforming Container is often a product of Speculative Generality, instead of a product of need. As such, the API is likely to be poorly suited to address real-world scenarios, be difficult to extent, and may exhibit churn in the form of frequent breaking changes.

- If Adapters are supplied by contributors (often the DI Container maintainers themselves), the Adapters may have varying quality levels, and may not support the latest version of the Conforming Container.

A code base using a Conforming Container may have code like this all over the place:

var foo = container.Resolve<IFoo>(); // ... use foo for something... var bar = container.Resolve<IBar>(); // ... use bar for something else... var baz = container.Resolve<IBaz>(); // ... use baz for something else again...

This breaks encapsulation, because it's impossible to identify a class' collaborators without reading its entire code base.

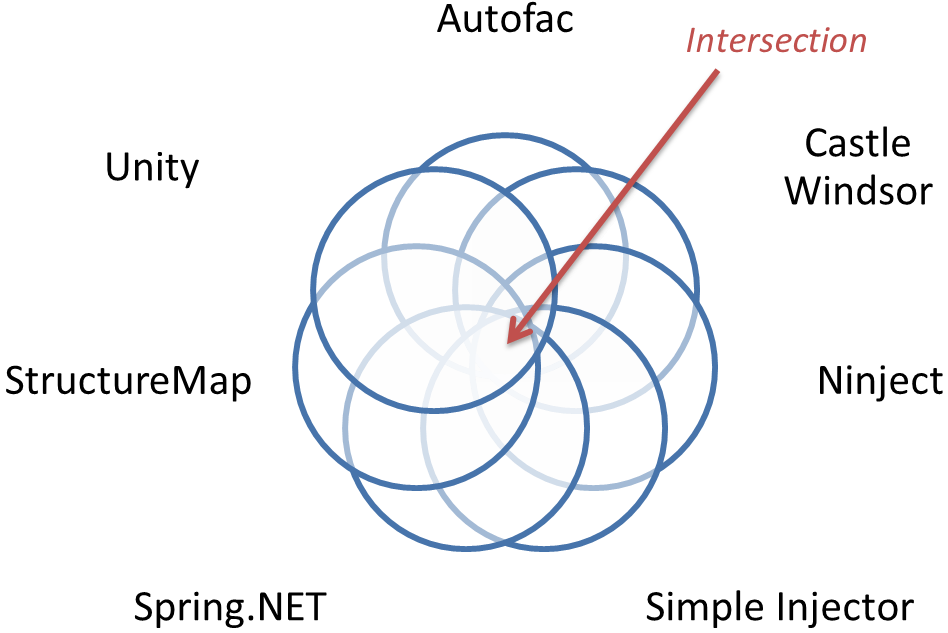

Additionally, concrete DI Containers have distinct feature sets. Although likely to be out of date by now, this feature comparison chart from my book illustrate this point:

| Castle Windsor | StructureMap | Spring.NET | Autofac | Unity | MEF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code as Configuration | x | x | x | x | ||

| Auto-registration | x | x | x | |||

| XML configuration | x | x | x | x | x | |

| Modular configuration | x | x | x | x | x | x |

| Custom lifetimes | x | x | (x) | x | ||

| Decommissioning | x | x | (x) | x | ||

| Interception | x | x | x |

This is only a simple chart that plots the most common features of DI Containers. Each DI Container has dozens of features - many of them unique to that particular DI Container. A Conforming Container can either support an intersection or union of all those features.

A Conforming Container that targets only the intersection of all features will be able to support only a small fraction of all available features, diminishing the value of the Conforming Container to the point where it becomes gratuitous.

A Conforming Container that targets the union of all features is guaranteed to consist mostly of a multitude of NotImlementedExceptions, or, put in another way, massively breaking the Liskov Substitution Principle.

Typical causes #

The typical causes of the Conforming Container anti-pattern are:

- Lack of understanding of Dependency Injection. Dependency Injection is a set of patterns driven by the Dependency Inversion Principle. A DI Container is an optional library, not a required part.

- A fear of letting an entire code base depend on a concrete DI Container, if that container turns out to be a poor choice. Few programmers have thouroughly surveyed all available DI Containers before picking one for a project, so architects desire to have the ability to replace e.g. StructureMap with Ninject.

- Library designers mistakenly thinking that Dependency Injection support involves defining a Conforming Container.

- Framework designers mistakenly thinking that Dependency Injection support involves defining a Conforming Container.

Known exceptions #

There are no cases known to me where a Conforming Container is a good solution to the problem at hand. There's always a better and simpler solution.

Refactored solution #

Instead of relying on the Service Locator anti-pattern, all collaborating classes should rely on the Constructor Injection pattern:

public class CorrectClient { private readonly IFoo foo; private readonly IBar bar; private readonly IBaz baz; public CorrectClient(IFoo foo, IBar bar, IBaz baz) { this.foo = foo; this.bar = bar; this.baz = baz; } public void DoSomething() { // ... use this.foo for something... // ... use this.bar for something else... // ... use this.baz for something else again... } }

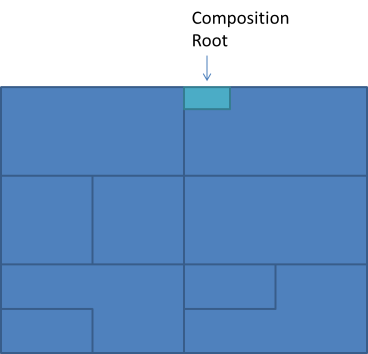

This leaves all options open for any code consuming the CorrectClient class. The only exception to relying on Constructor Injection is when you need to compose all these collaborating classes. The Composition Root has the single responsibility of composing all the objects into a working object graph:

public class CompositionRoot { public CorrectClient ComposeClient() { return new CorrectClient( new RealFoo(), new RealBar(), new RealBaz()); } }

In this example, the final graph is rather shallow, but it can be as complex and deep as necessary. This Composition Root uses hand-coded composition, but if you want to use a DI Container, the Composition Root is where you put it:

public class WindsorCompositionRoot { private readonly WindsorContainer container; public WindsorCompositionRoot() { this.container = new WindsorContainer(); // Configure the container here, // or better yet: use a WindsorInstaller } public CorrectClient ComposeClient() { return this.container.Resolve<CorrectClient>(); } }

This class (and perhaps a few auxiliary classes, such as a Windsor Installer) is the only class that uses a concrete DI Container. This is the Hollywood Principle in action. There's no reason to hide the DI Container behind an interface, because it has no clients. The DI Containers knows about the application; the application knows nothing about the DI Container.

In all but the most trivial of applications, the Composition Root is only an extremely small part of the entire application.

(The above picture is meant to illustrate an arbitrary application architecture; it could be layered, onion, hexagonal, or something else - it doesn't really matter.) If you want to replace one DI Container with another DI Container, you only replace the Composition Root; the rest of the application will never notice the difference.

Notice that only applications should have Composition Roots. Libraries and frameworks should not.

- Library classes should be defined with Constructor Injection throughout. If the library object model is very complex, a few Facades can be supplied to make it easier for library users to get started. See my article on DI-friendly libraries for more details.

- Frameworks should have appropriate hooks built in. These hooks should not be designed as Service Locators, but rather as Abstract Factories. See my article on DI-friendly frameworks for more details.

Variations #

Sometimes the Conforming Container only defines a Service Locator-like API, and sometimes it also defines a configuration API. That configuration API may include various axes of configurability, most notably lifetime management and decommisioning.

Decommissioning is often designed around the concept of a disposable 'context' scope, but as I explain in my book, that's not an extensible pattern.

Known examples #

There are various known examples of Conforming Containers for .NET:

- Common Service Locator

- ASP.NET MVC Dependency Resolver

- ASP.NET Web API Dependency Resolver

- NServiceBus IContainer

- Rebus container adapters

Configuring Azure Web Jobs

It's easy to configure Azure Web Jobs written in .NET.

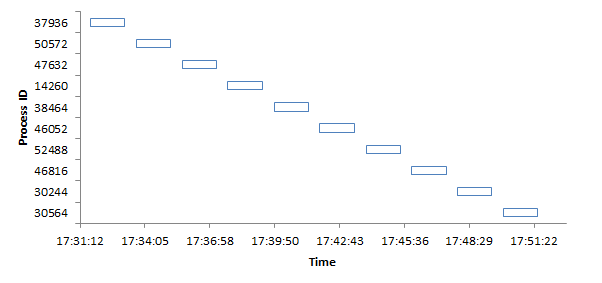

Azure Web Jobs is a nice feature for Azure Web Sites, because it enables you to bundle a background worker, scheduled batch job, etc. together with your Web Site. It turns out that this feature works pretty well, but it's not particularly well-documented, so I wanted to share a few nice features I've discovered while using them.

You can write a Web Job as a simple Command Line executable, but if you can supply command-line arguments to it, I have yet to discover how to do that. A good alternative is an app.config file with configuration settings, but it can be a hassle to deal with various configuration settings across different deployment environments. There's a simple solution to that.

CloudConfigurationManager #

If you use CloudConfigurationManager.GetSetting, configuration settings are read using various fallback mechanisms. The CloudConfigurationManager class is poorly documented, and I couldn't find documentation for the current version, but one documentation page about a deprecated version sums it up well enough:

"The GetSetting method reads the configuration setting value from the appropriate configuration store. If the application is running as a .NET Web application, the GetSetting method will return the setting value from the Web.config or app.config file. If the application is running in Windows Azure Cloud Service or in a Windows Azure Website, the GetSetting will return the setting value from the ServiceConfiguration.cscfg."That is probably still true, but I've found that it actually does more than that. As far as I can tell, it attempts to read configuration settings in this prioritized order:

- Try to find the configuration value in the Web Site's online configuration (see below).

- Try to find the configuration value in the .cscfg file.

- Try to find the configuration value in the app.config file or web.config file.

(It's possible that, under the hood, this UI actually maintains an auto-generated .cscfg file, in which case the first two bullet points above turn out to be one and the same.)

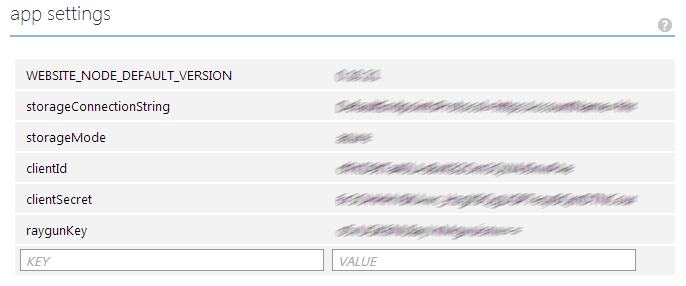

This is a really nice feature, because it means that you can push your deployments directly from your source control system (I use Git), and leave your configuration files empty in source control:

<appSettings> <add key="timeout" value="0:01:00" /> <add key="estimatedDuration" value="0:00:02" /> <add key="toleranceFactor" value="2" /> <add key="idleTime" value="0:00:05" /> <add key="storageMode" value="files" /> <add key="storageConnectionString" value="" /> <add key="raygunKey" value="" /> </appSettings>

Instead of having to figure out how to manage or merge those super-secret keys in the build system, you can simply shortcut the whole issue by not involving those keys in your build system; they're only stored in Azure - where you can't avoid having them anyway, because your system needs them in order to work.

Usage #

It's easy to use CloudConfigurationManager: instead of getting your configuration values with ConfigurationManager.AppSettings, you use CloudConfigurationManager.GetSetting:

let clientId = CloudConfigurationManager.GetSetting "clientId"

The CloudConfigurationManager class isn't part of the .NET Base Class Library, but you can easily add it from NuGet; it's called Microsoft.WindowsAzure.ConfigurationManager. The Azure SDK isn't required - it's just a stand-alone library with no dependencies, so I happily add it to my Composition Root when I know I'm going to deploy to an Azure Web Site.

Web Jobs #

Although I haven't found any documentation to that effect yet, a .NET console application running as an Azure Web Job will pick up configuration settings in the way described above. On other words, it shares configuration values with the web site that it's part of. That's darn useful.

Comments