Layers, Onions, Ports, Adapters: it's all the same by Mark Seemann

If you apply the Dependency Inversion Principle to Layered Architecture, you end up with Ports and Adapters.

One of my readers, Giorgio Sala, asks me:

In his book "Implementing DDD" mr Vernon talks a lot about the Ports and Adapter architecture as a next level step of the Layered architecture. I would like to know your thinking about it.

The short answer is that this is more or less the architecture I describe in my book, although in the book, I never explicitly call it out by that name.

Layered architecture #

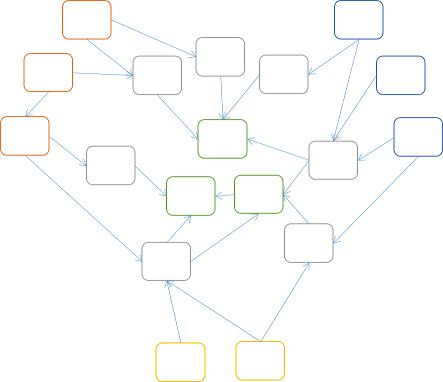

In my book, I describe the common pitfalls of a typical layered architecture. For example, in chapter 2, I analyse a typical approach to layered architecture; it's an example of what not to do. Paraphrased from the book's figure 2.13, the erroneous implementation creates this dependency graph:

The arrows show the direction of dependencies; i.e. the User Interface library depends on the Domain library, which in turn depends on the Data Access library. This violates the Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP), because the Domain library depends on the Data Access library, and the DIP says that:

Abstractions should not depend upon details. Details should depend upon abstractions.

Later in chapter 2, and throughout the rest of my book, I demonstrate how to invert the dependencies. Paraphrased, figure 2.12 looks like this:

This is almost the same figure as the previous, but notice that the direction of dependency has changed, so that the Data Access library now depends on the Domain library, instead of the other way around. This is the DIP applied: the details (UI, Data Access) depend on the abstractions (the Domain Model).

Onion layers #

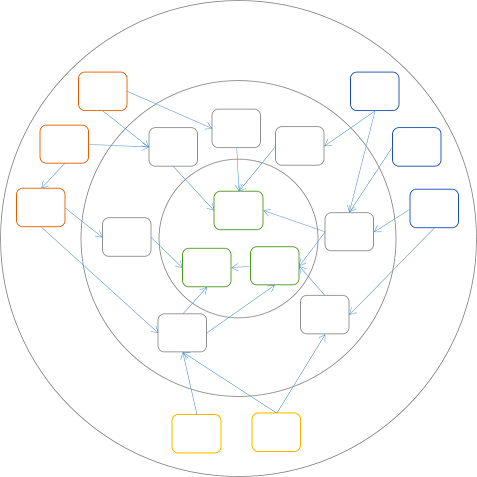

The example from chapter 2 in my book is obviously simplified, with only three libraries involved. Imagine a generalized architecture following the DIP:

While there are many more libraries, notice that all dependencies still point inwards. If you're still thinking in terms of layers, you can draw concentric layers around the boxes:

These concentric layers resemble the layers of an onion, so it's not surprising that Jeffrey Palermo calls this type of architecture for Onion Architecture.

The DIP still applies, so dependencies can only go in one direction. However, it would seem that I've put the UI components (the orange boxes) and the Data Access components (the blue boxes) in the same layer. (Additionally, I've added some yellow boxes that might symbolise unit tests.) This may seem unfamiliar, but actually makes sense, because the components in the outer layer are all at the boundaries of the application. Some boundaries (such as UI, RESTful APIs, message systems, etc.) face outward (to the internet, extranets, etc.), while other boundaries (e.g. databases, file systems, dependent web services, etc.) face inward (to the OS, database servers, etc.).

As the diagram implies, components can depend on other components within the same layer, but does that mean that UI components can talk directly to Data Access components?

Hexagonal architecture #

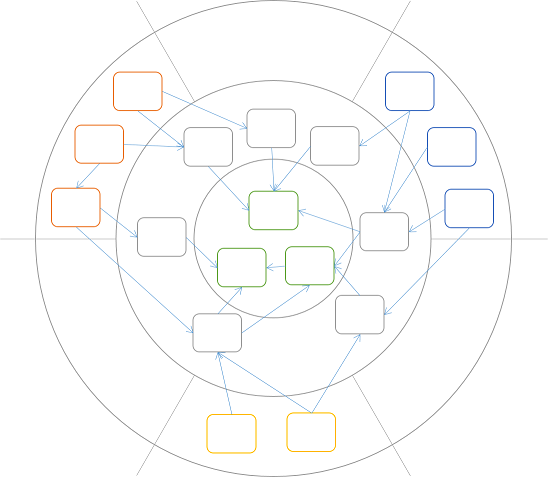

While traditional Layered Architecture is no longer the latest fad, it doesn't mean that all of its principles are wrong. It's still not a good idea to allow UI components to depend directly on the Data Access layer; it would couple such components together, and you might accidentally bypass important business logic.

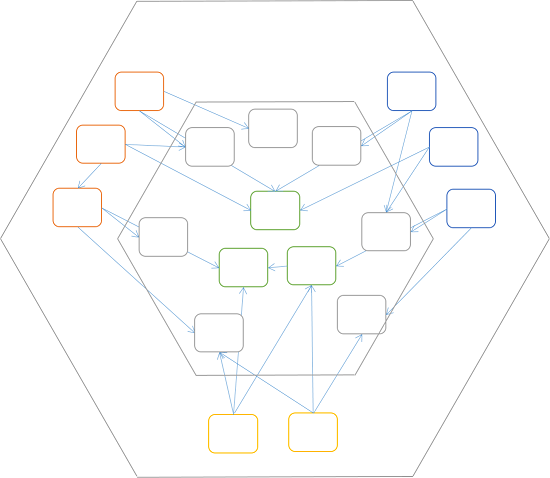

You have probably noticed that I've grouped the orange, yellow, and blue boxes into separate clusters. This is because I still want to apply the old rule that UI components must not depend on Data Access components, and vice versa. Therefore, I introduce bulkheads between these groups:

Although it may seem a bit accidental that I end up with exactly six sections (three of them empty), it does nicely introduce Alistair Cockburn's closely related concept of Hexagonal Architecture:

You may feel that I cheated a bit in order to make my diagram hexagonal, but that's okay, because there's really nothing inherently hexagonal about Hexagonal Architecture; it's not a particularly descriptive name. Instead, I prefer the alternative name Ports and Adapters.

Ports and Adapters #

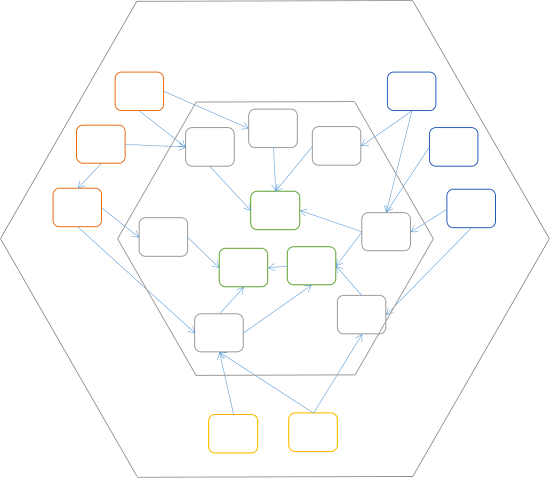

The only thing still bothering me with the above diagram is that the dependency hierarchy is too deep (at least conceptually). When the diagram consisted of concentric circles, it had three (onion) layers. The hexagonal dependency graph above still has those intermediary (grey) components, but as I've previously attempted to explain, the flatter the dependency hierarchy, the better.

The last step, then, is to flatten the dependency hierarchy of the inner hexagon:

The components in the inner hexagon have few or no dependencies on each other, while components in the outer hexagon act as Adapters between the inner components, and the application boundaries: its ports.

Summary #

In my book, I never explicitly named the architecture I describe, but essentially, it is the Ports and Adapters architecture. There are other possible application architectures than the variations described here, and some of them still work well with Dependency Injection, but the main architectural emphasis in Dependency Injection in .NET is Ports and Adapters, because I judged it to be the least foreign for the majority of the book's readers.

The reason I never explicitly called attention to Ports and Adapters or Onion Architecture in my book is that I only became aware of these pattern names as I wrote the book. At that time, I didn't feel confident that what I did matched those patterns, but the more I've learned, the more I've become convinced that this was what I'd been doing all along. This just confirms that Ports and Adapters is a bona fide pattern, because one of the attributes of patterns is that they materialize independently in different environments, and are then subsequently discovered as patterns.