Argument list isomorphisms by Mark Seemann

There are many ways to represent an argument list. An overview for object-oriented programmers.

This article is part of a series of articles about software design isomorphisms.

Most programming languages enable you to pass arguments to operations. In C# and Java, you declare methods with a list of arguments:

public Foo Bar(Baz baz, Qux qux)

Here, baz and qux are arguments to the Bar method. Together, the arguments for a method is called an argument list. To be clear, this isn't universally adopted terminology, but is what I'll be using in this article. Sometimes, people (including me) say parameter instead of argument, and I'm not aware of any formal specification to differentiate the two.

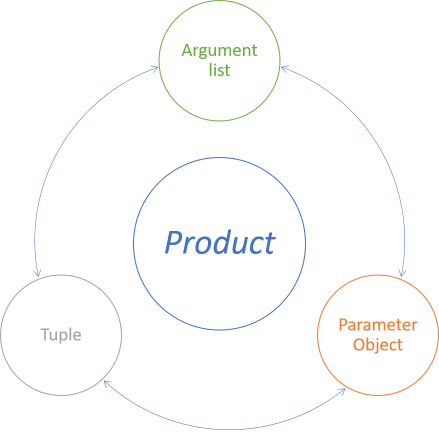

While you can pass arguments as a flat list, you can also model them as parameter objects or tuples. These representations are equivalent, because lossless translations between them exist. We say that they are isomorphic.

Isomorphisms #

In theory, you can declare a method that takes thousands of arguments. In practice, you should constrain your design to as few arguments as possible. As Refactoring demonstrates, one way to do that is to Introduce Parameter Object. That, already, teaches us that there's a mapping from a flat argument list to a Parameter Object. Is there an inverse mapping? Do other representations exist?

There's at least three alternative representations of a group of arguments:

- Argument list

- Parameter Object

- Tuple

Argument list/Parameter Object isomorphism #

Perhaps the best-known mapping from an argument list is the Introduce Parameter Object refactoring described in Refactoring.

Since the refactoring is described in detail in the book, I don't want to repeat it all here, but in short, assume that you have a method like this:

public Bar Baz(Qux qux, Corge corge)

In this case, the method only has two arguments, so the refactoring may not be necessary, but that's not the point. The point is that it's possible to refactor the code to this:

public Bar Baz(BazParameter arg)

where BazParameter looks like this:

public class BazParameter { public Qux Qux { get; set; } public Corge Corge { get; set; } }

In Refactoring, the recipe states that you should make the class immutable, and while that's a good idea (I recommend it!), it's technically not necessary in order to perform the translation, so I omitted it here in order to make the code simpler.

You're probably able to figure out how to translate back again. We could call this refactoring Dissolve Parameter Object:

- For each field or property in the Parameter Object, add a new method argument to the target method.

- At all call sites, pass the Parameter Object's field or property value as each of those new arguments.

- Change the method body so that it uses each new argument, instead of the Parameter Object.

- Remove the Parameter Object argument, and update call sites accordingly.

As an example, consider the Roster example from a previous article. The Combine method on the Roster class is implemented like this:

public Roster Combine(Roster other) { return new Roster( this.Girls + other.Girls, this.Boys + other.Boys, this.Exemptions.Concat(other.Exemptions).ToArray()); }

This method takes an object as a single argument. You can think of this Roster object as a Parameter Object.

If you like, you can add a method overload that dissolves the Roster object to its constituent values:

public Roster Combine( int otherGirls, int otherBoys, params string[] otherExemptions) { return this.Combine( new Roster(otherGirls, otherBoys, otherExemptions)); }

In this incarnation, the dissolved method overload creates a new Roster from its argument list and delegates to the other overload. This is, however, an arbitrary implementation detail. You could just as well implement the two methods the other way around:

public Roster Combine(Roster other) { return this.Combine( other.Girls, other.Boys, other.Exemptions.ToArray()); } public Roster Combine( int otherGirls, int otherBoys, params string[] otherExemptions) { return new Roster( this.Girls + otherGirls, this.Boys + otherBoys, this.Exemptions.Concat(otherExemptions).ToArray()); }

In this variation, the overload that takes three arguments contains the implementation, whereas the Combine(Roster) overload simply delegates to the Combine(int, int, string[]) overload.

In order to illustrate the idea that both APIs are equivalent, in this example I show two method overloads side by side. The overall point, however, is that you can translate between such two representations without changing the behaviour of the system. You don't have to keep both method overloads in place together.

Argument list/tuple isomorphism #

In relationship to statically typed functional programming, the term argument list is confounding. In the functional programming languages I've so far dabbled with (F#, Haskell, PureScript, Clojure, Erlang), the word list is used synonymously with linked list.

As a data type, a linked list can hold an arbitrary number of elements. (In Haskell, it can even be infinite, because Haskell is lazily evaluated.) Statically typed languages like F# and Haskell add the constraint that all elements must have the same type.

An argument list like (Qux qux, Corge corge) isn't at all a statically typed linked list. Neither does it have an arbitrary size nor does it contain elements of the same type. On the contrary, it has a fixed length (two), and elements of different types. The first element must be a Qux value, and the second element must be a Corge value.

That's not a list; that's a tuple.

Surprisingly, Haskell may provide the most digestible illustration of that, even if you don't know how to read Haskell syntax. Suppose you have the values qux and corge, of similarly named types. Consider a C# method call Baz(qux, corge). What's the type of the 'argument list'?

λ> :type (qux, corge) (qux, corge) :: (Qux, Corge)

:type is a GHCi command that displays the type of an expression. By coincidence (or is it?), the C# argument list (qux, corge) is also valid Haskell syntax, but it is syntax for a tuple. In this example, the tuple is a pair where the first element has the type Qux, and the second element has the type Corge, but (foo, qux, corge) would be a triple, (foo, qux, corge, grault) would be a quadruple, and so on.

We know that the argument list/tuple isomorphism exists, because that's how the F# compiler works. F# is a multi-paradigmatic language, and it can interact with C# code. It does that by treating all C# argument lists as tuples. Consider this example of calling Math.Pow:

let i = Math.Pow(2., 4.)

Programmers who still write more C# than F# often write it like that, because it looks like a method call, but I prefer to insert a space between the method and the arguments:

let i = Math.Pow (2., 4.)

The reason is that in F#, function calls are delimited with space. The brackets are there in order to override the normal operator precedence, just like you'd write (1 + 2) * 3 in order to get 9 instead of 7. This is better illustrated by introducing an intermediate value:

let t = (2., 4.) let i = Math.Pow t

or even

let t = 2., 4. let i = Math.Pow t

because the brackets are now redundant. In the last two examples, t is a tuple of two floating-point numbers. All four code examples are equivalent and compile, thereby demonstrating that a translation exist from F# tuples to C# argument lists.

The inverse translation exists as well. You can see a demonstration of this in the (dormant) Numsense code base, which includes an object-oriented Façade, which defines (among other things) an interface where the TryParse method takes a tuple argument. Here's the declaration of that method:

abstract TryParse : s : string * [<Out>]result : int byref -> bool

That looks cryptic, but if you remove the [<Out>] annotation and the argument names, the method is declared as taking single input value of the type string * int byref. It's a single value, but it's a tuple (a pair).

Perhaps it's easier to understand if you see an implementation of this interface method, so here's the English implementation:

member this.TryParse (s, result) = Helper.tryParse Numeral.tryParseEnglish (s, &result)

You can see that, as I've described above, I've inserted a space between this.TryParse and (s, result), in order to highlight that this is an F# function that takes a single tuple as input.

In C#, however, you can use the method as though it had a standard C# argument list:

int i; var success = Numeral.English.TryParse( "one-thousand-three-hundred-thirty-seven", out i);

You'll note that this is an advanced example that involves an out parameter, but even in this edge case, the translation is possible.

C# argument lists and F# tuples are isomorphic. I'd be surprised if this result doesn't extend to other languages.

Parameter Object/tuple isomorphism #

The third isomorphism that I claim exists is the one between Parameter Objects and tuples. If, however, we assume that the two above isomorphisms hold, then this third isomorphism exists as well. I know from my copy of Conceptual Mathematics that isomorphisms are transitive. If you can translate from Parameter Object to argument list, and from argument list to tuple, then you can translate from Parameter Object to tuple; and vice versa.

Thus, I'm not going to use more words on this isomorphism.

Summary #

Argument lists, Parameter Objects, and tuples are isomorphic. This has a few interesting implications, first of which is that because all these refactorings exist, you can employ them. If a method's argument list is inconvenient, consider introducing a Parameter Object. If your Parameter Object starts to look so generic that you have a hard time coming up with good names for its elements, perhaps a tuple is more appropriate. On the other hand, if you have a tuple, but it's unclear what role each unnamed element plays, consider refactoring to an argument list or Parameter Object.

Another important result is that since these three ways to model arguments are isomorphic, we can treat them as interchangeable in analysis. For instance, from category theory we can learn about the properties of tuples. These properties, then, also apply to C# and Java argument lists.

Next: Uncurry isomorphisms.