Conway's Law: latency versus throughput by Mark Seemann

Organising work in one way optimises for low latency; in another for throughput.

It's a cliché that the software industry is desperate for talent. I also believe that it's a myth. As I've previously observed, the industry seems desperate for talent within commute range. The implication is that although we perform some of the most intangible and digitised work imaginable, we're expected to be physically present in an office.

Since 2014 I've increasingly been working from home, and I love it. I also believe that it's an efficient way to develop software, but not only for the reasons usually given.

I believe that distributed, asynchronous software development optimises throughput, but may sacrifice reaction time (i.e. increase latency).

The advantages of working in an office #

It's easy to criticise office work, but if it's so unpopular, why is it still the mainstream?

I think that there's a multitude of answers to that question. One is that this may be the only way that management can imagine. Since programming is so intangible, it's impossible to measure productivity. What a manager can do, though, is to watch who arrives early, who's the last to leave, and who seems to be always in front of his or her computer, or in a meeting, and so on.

Another answer to the question is that people actually like working together. I currently advice IDQ on software development principles and architecture. They have a tight-knit development team. The first day I visited them, I could feel a warm and friendly vibe. I've been visiting them regularly for about a year, now, and the first impression has proven correct. As we Danes say, that work place is positively hyggelig.

Some people also prefer to go to the office to have a formal boundary between their professional and private lives.

Finally, if you're into agile software development, you've probably heard about the benefits of team co-location.

When the team is located in the same room, working towards the same goals, communication is efficient - or is it?

You can certainly get answers to your questions quickly. All you have to do is to interrupt the person who can answer. If you don't know who that is, you just interrupt everybody until you've figured it out. While offices are interruption factories (as DHH puts it), this style of work can reduce latency.

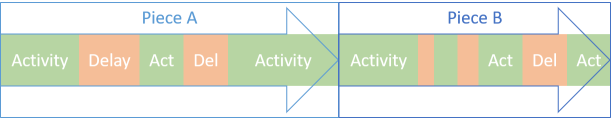

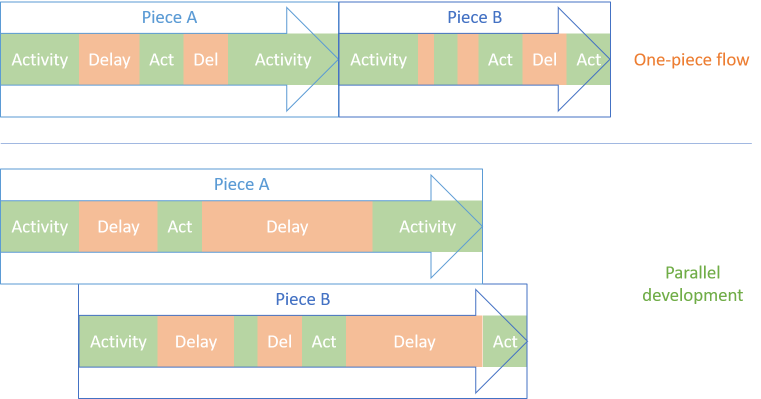

If you explicitly follow e.g. lean software development and implement something like one-piece flow, you can reduce your cycle time. The less delay between activities, the faster you can deliver value. Once you've delivered one piece (e.g. a feature), you move on to the next.

If this is truly the goal, then putting all team members in the same office makes sense. You don't get higher communications bandwidth than when you're physically together. All the subtle intonations of the way your colleagues speak, the non-verbal cues, etcetera are there if you know how to interpret them.

Consequences of team co-location #

I've seen team co-location work for small teams. People can pair program or even mob program. You can easily draw on the expertise of your co-workers. It does require, however, that everyone respects boundaries.

It's a balancing act. You may get your answer sooner, but your interruption could break your colleague's concentration. The net result could be negative productivity.

While I've seen team co-location work, I've seen it fail more frequently. There are many reasons for this.

First, there's all the interruptions. Most programmers don't like being interrupted.

Second, the opportunity for ad-hoc communication easily leads to poor software architecture. This follows from Conway's law, which argues that

"Any organization that designs a system [...] will inevitably produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization's communication structure."

I know that it's not a law in any rigid sense of the word, but it can often be fruitful to keep an eye out for this sort of interaction. Based on my experience, it seems to happen often.

Ad-hoc office communication leads to ad-hoc communication structures in the code. There's typically little explicit architecture. Knowledge is in the heads of people.

Such an organisation tends to have an oral culture. There's no permanence of knowledge, no emphasis on readability of code (because you can always ask someone if there's code you don't understand), and meetings all the time.

I once worked as a consultant for a company where there was only one old-timer around. He spent most of his time in meetings, because he knew all the intricate details of how everything worked and talked together, and other people needed to know.

After I'd been involved with that (otherwise wonderful) company on and off for a few years, I accumulated some knowledge as well, and people wanted to have meetings with me.

In the beginning, I obliged. Then it turned out that a week after I'd had a meeting, I'd be called to what would essentially be the same meeting again. Why? Because some other stakeholder heard about the first meeting and decided that he or she also required that information. The solution? Call another meeting.

My counter-move was to begin to write things down. When people would call a meeting, I'd ask for an agenda. That alone filtered away more than half of the meetings. When I did receive an agenda, I could often reply:

"Based on the agenda, I believe you'll find everything you need to know here. If not, please let me know what's missing so that I can update the document"

I'd attach said document. By doing that, I eliminated ninety percent of my meetings.

Notice what I did. I changed the communication structure - at least locally around me. Soon after, I went remote with that client, and had a few successful years doing that.

I hope that the previous section outlined that working in an office can be effective, but as I've now outlined, it can also be dysfunctional.

If you truly must deliver as soon as possible, because if you don't, the organisation isn't going to be around in five years, office work, with its low communications latency may be the best option.

Remote office work #

I often see companies advertise for programmers. When remote work is an option, it often comes with the qualification that it must be within a particular country, or a particular time zone.

There can be legal or bureaucratic reasons why a company only wants to hire within a country. I get that, but I consider a time zone requirement a danger sign. The same goes for "we use Slack" or whatever other 'team room' instant messaging technology is cool these days.

That tells me that while the company allows people to be physically not in the office, they must still obey office hours. This indicates to me that communication remains ad-hoc and transient. Again, code quality suffers.

These days, because of the Corona virus, many organisations deeply entrenched in the oral culture of co-location find that they must now work as a distributed team. They try to address the situation by setting up day-long video conference calls.

It may work in an office, but it's not the best fit for a distributed team.

Distributed asynchronous software development #

Decades of open-source development has shown another way. Successful open-source software (OSS) projects are distributed and use asynchronous communication channels (mailing lists, issue trackers). It's worth considering the causation. I don't think anyone sat down and decided to do it this way in order to be successful. I think that the OSS projects that became successful became successful exactly because they organised work that way.

When contributions are voluntary, you have to cast a wide net. A successful OSS project should accept contributions from around the world. If an excellent contribution from Japan falters because the project team is based in the US, and immediate, real-time communication is required, then that project has odds against it.

An OSS project that works asynchronously can receive contributions from any time zone. The disadvantage can be significant communication lag.

If you get a contribution from Australia, but you're in Europe, you may send a reply asking for clarifications or improvements. At the time you do that, the contributor may have already gone to bed. He or she isn't going to reply later, at which time you've gone to bed.

It can take days to get anything done. That doesn't sound efficient, and if you're in a one-piece flow mindset it isn't. You need to enable parallel development. If you do that, you can work on something else while you wait for your asynchronous collaborator to respond.

In this diagram, the wait-times in the production of one piece (e.g. one feature) can be used to move forward with another feature. The result is that you may actually be able to finish both tasks sooner than if you stick strictly to one-piece flow.

Before you protest: in reality, delay times are much longer than implied by the diagram. An activity could be something as brief as responding to a request for more information. You may be able to finish this activity in 30 minutes, whereafter the delay time is another twenty hours. Thus, in order to keep throughput comparable, you need to juggle not two, but dozens of parallel processes.

You may also feel the urge to protest that the diagram postulates a false dichotomy. That's not my intention. Even with co-location, you could do parallel development.

There's also the argument that parallel development requires context switching. That's true, and it comes with overhead.

My argument is only this: if you decide to shift to an asynchronous process, then I consider parallel development essential. Even with parallel development, you can't get the same (low) latency as is possible in the office, but you may be able to get better throughput.

This again has implications for software architecture. Parallel development works when features can be developed independently of each other - when there's only minimal dependencies between various areas of the code.

Conway's law is relevant here as well. If you decouple the communication between various parts of the system, you can also decouple the development of said parts. Ultimately, the best fit for a distributed, asynchronous software development process may be a distributed, asynchronous system.

Quadrants #

This is the point where, if this was a Gartner report, it'd include a 2x2 table with four quadrants. It's not, but I'll supply it anyway:

| Synchronous | Asynchronous | |

| Distributed | Virtual office | OSS-like parallel development |

| Co-located | Scrum, XP, etc. | Emailing the person next to you |

I've yet to discuss the fourth quadrant. This is where people sit next to each other, yet still email each other. That's just weird. Like the virtual office, I don't think it's a long-term sustainable process. The advantages of just talking to each other is just too great. If you're co-located, ad-hoc communication is possible, so that's where the software architecture will gravitate as well. Again, Conway's law applies.

If you want to move towards a sustainable distributed process, you should consider adjusting everything accordingly. A major endeavour in that shift involves migrating from an oral to a written culture. Basecamp has a good guide to get you started.

Your writer reveals himself #

I intend this to be an opinion piece. It's based on a combination of observations made by others, mixed with my personal experiences, but I also admit that it's coloured by my personal preferences. I strongly prefer distributed, asynchronous processes with an emphasis on written communication. Since this blog contains more than 500 articles, it should hardly come as a surprise to anyone that I'm a prolific writer.

I've had great experiences with distributed, asynchronous software development. One such experience was the decade I led the AutoFixture open-source project. Other experiences include a handful of commercial, closed-source projects where I did the bulk of the work remotely.

This style of work benefits my employer. By working asynchronously, I have to document what I do, and why I do it. I leave behind a trail of text artefacts other people can consult when I'm not available.

I like asynchronous processes because they liberate me to work when I want to, where I want to. I take advantage of this to go for a run during daylight hours (otherwise an issue during Scandinavian winters), to go grocery shopping outside of rush hour, to be with my son when he comes home from school, etcetera. I compensate by working at other hours (evenings, weekends). This isn't a lifestyle that suits everyone, but it suits me.

This preference produces a bias in the way that I see the world. I don't think I can avoid that. Like DHH I view offices as interruption factories. I self-identify as an introvert. I like being alone.

Still, I've tried to describe some forces that affect how work is done. I've tried to be fair to co-location, even though I don't like it.

Conclusion #

Software development with a co-located team can be efficient. It offers the benefits of high-bandwidth communication, pair programming, and low-latency decision making. It also implies an oral tradition. Knowledge has little permanence and the team is vulnerable to key team members going missing.

While such a team organisation can work well when team members are physically close to each other, I believe that this model comes under pressure when team members work remotely. I haven't seen the oral, ad-hoc team process work well in a distributed setting.

Successful distributed software development is asynchronous and based on a literate culture. It only works if the software architecture allows it. Code has to be decoupled and independently deployable. If it is, though, you can perform work in parallel. Conway's law still applies.