Accountability and free speech by Mark Seemann

A most likely naive suggestion.

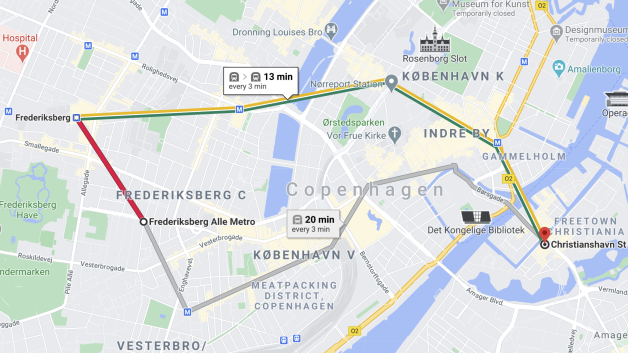

A few years ago, my mother (born 1940) went to Paris on vacation with her older sister. She was a little concerned if she'd be able to navigate the Métro, so she asked me to print out all sorts of maps in advance. I wasn't keen on another encounter with my nemesis, the printer, so I instead showed her how she could use Google Maps to get on-demand routes. Google Maps now include timetables and line information for many metropolitan subway lines around the world. I've successfully used it to find my way around London, Paris, New York, Tokyo, Sydney, and Melbourne.

It even works in my backwater home-town:

It's rapidly turning into indispensable digital infrastructure, and that's beginning to trouble me.

You can still get paper maps of the various rapid transit systems around the world, but for how long?

Digital infrastructure #

If you're old enough, you may remember phone books. In the days of land lines and analogue phones, you'd look up a number and then dial it. As the internet became increasingly ubiquitous, phone directories went online as well. Paper phone books were seen as waste, and ultimately disappeared from everyday life.

You can think of paper phone books as a piece of infrastructure that's now gone. I don't miss them, but it's worth reflecting on what impact their disappearing has. Today, if I need to find a phone number, Google is often the place I go. The physical infrastructure is gone, replaced by a digital infrastructure.

Google, in particular, now provides important infrastructure for modern society. Not only web search, but also maps, video sharing, translation, emails, and much more.

Other companies offer other services that verge on being infrastructure. Facebook is more than just updates to friends and families. Many organisations, including schools and universities, coordinate activities via Facebook, and the political discourse increasingly happens there and on Twitter.

We've come to rely on these 'free' services to a degree that resembles our reliance on physical infrastructure like the power grid, running water, roads, telephones, etcetera.

TANSTAAFL #

Robert A. Heinlein coined the phrase There ain't no such thing as a free lunch (TANSTAAFL) in his excellent book The Moon is a Harsh Mistress. Indeed, the digital infrastructure isn't free.

Recent events have magnified some of the cost we're paying. In January, Facebook and Twitter suspended the then-president of the United States from the platforms. I've little sympathy for Donald Trump, who strikes me as an uncouth narcissist, but since I'm a Danish citizen living in Denmark, I don't think that I ought to have much of an opinion about American politics.

I do think, on the other hand, that the suspension sets an uncomfortable precedent.

Should we let a handful of tech billionaires control essential infrastructure? This time, the victim was someone half the world was glad to see go, but who's next? Might these companies suspend the accounts of politicians who work against them?

Never in the history of the world has decision power over so many people been so concentrated. I'll remind my readers that Facebook, Twitter, Google, etcetera are in worldwide use. The decisions of a handful of majority shareholders can now affect billions of people.

If you're suspended from one of these platforms, you may lose your ability to participate in school activities, or from finding your way through a foreign city, or from taking part of the democratic discussion.

The case for regulation #

In this article, I mainly want to focus on the free-speech issue related mostly to Facebook and Twitter. These companies make money from ads. The longer you stay on the platform, the more ads they can show you, and they've discovered that nothing pulls you in like anger. These incentives are incredibly counter-productive for society.

Users are implicitly encouraged to create or spread anger, yet few are held accountable. One reason is that you can easily create new accounts without disclosing your real-world identity. This makes it difficult to hold users accountable for their utterances.

Instead of clear rules, users are suspended for inexplicable and arbitrary reasons. It seems that these are mostly the verdicts of algorithms, but as we've seen in the case of Donald Trump, it can also be the result of an undemocratic, but political decision.

Everyone can lose their opportunities for self-expression for arbitrary reasons. This is a free-speech issue.

Yes, free speech.

I'm well aware that Facebook and Twitter are private companies, and no-one has any right to an account on those platforms. That's why I started this essay by discussing how these services are turning into infrastructure.

More than a century ago, the telephone was new technology operated by private companies. I know the Danish history best, but it serves well as an example. KTAS, one of the world's first telephone companies, was a private company. Via mergers and acquisitions, it still is, but as it grew and became the backbone of the country's electronic communications network, the government introduced legislation. For decades, it and its sister companies were regional monopolies.

The government allowed the monopoly in exchange for various obligations. Even when the monopoly ended in 1996, the original monopoly companies inherited these legal obligations. For instance, every Danish citizen has the right to get a land-line installed, even if that installation by itself is a commercial loss for the company. This could be the case on certain remote islands or other rural areas. The Danish state compensates the telephone operator for this potential loss.

Many other utility companies run in a similar fashion. Some are semi-public, some are private, but common to water, electricity, garbage disposal, heating, and other operators is that they are regulated by government.

When a utility becomes important to the functioning of society, a sensible government steps in to regulate it to ensure the further smooth functioning of society.

I think that the services offered by Google, Facebook, and Twitter are fast approaching a level of significance that ought to trigger government regulation.

I don't say that lightly. I'm actually quite libertarian in my views, but I'm no anarcho-libertarian. I do acknowledge that a state offers essential services such as protection of property rights, a judicial system, and so on.

Accountability #

How should we regulate social media? I think we should start by exchanging accountability for the right to post.

Let's take another step back for a moment. For generations, it's been possible to send a letter to the editor of a regular newspaper. If the editor deems it worthy for publication, it'll be printed in the next issue. You don't have any right to get your letter published; this happens at the discretion of the editor.

Why does it work that way? It works that way because the editor is accountable for what's printed in the paper. Ultimately, he or she can go to jail for what's printed.

Freedom of speech is more complicated than it looks at first glance. For instance, censorship in Denmark was abolished with the 1849 constitution. This doesn't mean that you can freely say whatever you'd like; it only means that government has no right to prevent you from saying or writing something. You can still be prosecuted after the fact if you say or write something libellous, or if you incite violence, or if you disclose secrets that you've agreed to keep, etcetera.

This is accountability. It works when the person making the utterance is known and within reach of the law.

Notice, particularly, that an editor-in-chief is accountable for a newspaper's contents. Why isn't Facebook or Twitter accountable for content?

These companies have managed to spin a story that they're platforms rather than publishers. This argument might have had some legs ten years ago. When I started using Twitter in 2009, the algorithm was easy to understand: My feed showed the tweets from the accounts that I followed, in the order that they were published. This was easy to understand, and Twitter didn't, as far as I could tell, edit the feed. Since no editing took place, I find the platform argument applicable.

Later, the social networks began editing the feeds. No humans were directly involved, but today, some posts are amplified while others get little attention. Since this is done by 'algorithms' rather than editors, the companies have managed to convince lawmakers that they're still only platforms. Let's be real, though. Apparently, the public needs a programmer to say the following, and I'm a programmer.

Programmers, employees of those companies, wrote the algorithms. They experimented and tweaked those algorithms to maximise 'engagement'. Humans are continually involved in this process. Editing takes place.

I think it's time to stop treating social media networks as platforms, and start treating them as publishers.

Practicality #

Facebook and Twitter will protest that it's practically impossible for them to 'edit' what happens on the networks. I find this argument unconvincing, since editing already takes place.

I'd like to suggest a partial way out, though. This brings us back to regulation.

I think that each country or jurisdiction should make it possible for users to opt in to being accountable. Users should be able to verify their accounts as real, legal persons. If they do that, their activity on the platform should be governed by the jurisdiction in which they reside, instead of by the arbitrary and ill-defined 'community guidelines' offered by the networks. You'd be accountable for your utterances according to local law where you live. The advantage, though, is that this accountability buys you the right to be present on the platform. You can be sued for your posts, but you can't be kicked off.

I'm aware that not everyone lives in a benign welfare state such as Denmark. This is why I suggest this as an option. Even if you live in a state that regulates social media as outlined above, the option to stay anonymous should remain. This is how it already works, and I imagine that it should continue to work like that for this group of users. The cost of staying anonymous, though, is that you submit to the arbitrary and despotic rules of those networks. For many people, including minorities and citizens of oppressive states, this is likely to remain a better trade-off.

Problems #

This suggestion is in no way perfect. I can already identify one problem with it.

A country could grant its citizens the right to conduct infowar on an adversary; think troll armies and the like. If these citizens are verified and 'accountable' to their local government, but this government encourages rather than punishes incitement to violence in a foreign country, then how do we prevent that?

I have a few half-baked ideas, but I'd rather leave the problem here in the hope that it might inspire other people to start thinking about it, too.

Conclusion #

This is a post that I've waited for a long time for someone else to write. If someone already did, I'm not aware of it. I can think of three reasons:

- It's a really stupid idea.

- It's a common idea, but no-one talks about it because of pluralistic ignorance.

- It's an original idea that no-one else have had.

The idea is, in short, to make it optional for users to 'buy' the right to stay on a social network for the price of being held legally accountable. This requires some national as well as international regulation of the digital infrastructure.

Could it work? I don't know, but isn't it worth discussing?

Comments

Hi Mark, I would just like to say that I like the idea :)

Thank you for writing this.