Some thoughts on the economics of programming by Mark Seemann

On the net value of process and code quality.

Once upon a time there was a software company that had a special way of doing things. No other company had ever done things quite like that before, but the company had much success. In short time it rose to dominance in the market, outcompeting all serious competition. Some people disliked the company because of its business tactics and sheer size, but others admired it.

Even more wanted to be like it.

How did the company achieve its indisputable success? It looked as though it was really, really good at making software. How did they write such good software?

It turned out that the company had a special software development process.

Other software organisations, hoping to be able to be as successful, tried to copy the special process. The company was willing to share. Its employees wrote about the process. They gave conference presentations on their special sauce.

Which company do I have in mind, and what was the trick that made it so much better than its competition? Was it microservices? Monorepos? Kubernetes? DevOps? Serverless?

No, the company was Microsoft and the development process was called Microsoft Solutions Framework (MSF).

What?! do you say.

You've never heard of MSF?

That's hardly surprising. I doubt that MSF was in any way related to Microsoft's success.

Net profits #

These days, many people in technology consider Microsoft an embarrassing dinosaur. While you know that it's still around, does it really matter, these days?

You can't deny, however, that Microsoft made a lot of money in the Nineties. They still do.

What's the key to making a lot of money? Have a revenue larger than your costs.

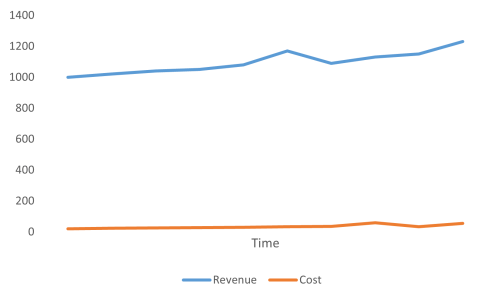

I'm too lazy to look up the actual numbers, but clearly Microsoft had (and still has) a revenue vastly larger than its costs:

Compared to real, historic numbers, this may be exaggerated, but I'm trying to make a general point - not one that hinges on actual profit numbers of Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Google, or any other tremendously profitable company. I'm also aware that real companies have costs that aren't directly related to software development: Marketing, operations, buildings, sales, etcetera. They also make money in other ways than from their software, mainly from investments of the profits.

The difference between the revenue and the cost is the profit or net value.

If the graph looks like the above, is managing cost the main cause of success? Hardly. The cost is almost a rounding error on the profits.

If so, is the technology or process key to such a company's success? Was it MSF that made Microsoft the wealthiest company in the world? Are two-pizza teams the only explanation of Amazon's success? Is Google the dominant search engine because the source code is organised in a monorepo?

I'd be surprised were that the case. Rather, I think that these companies were at the right place at the right time. While there were search engines before Google, Google was so much better that users quickly migrated. Google was also better at making money than earlier search engines like AltaVista or Yahoo! Likewise, Microsoft made more successful PC operating systems than the competition (which in the early Windows era consisted exclusively of OS/2) and better professional software (word processor, spreadsheet, etcetera). Amazon made a large-scale international web shop before anyone else. Apple made affordable computers with graphical user interfaces before other companies. Later, they introduced a smartphone at the right time.

All of this is simplified. For example, it's not really true that Apple made the first smartphone. When the iPhone was introduced, I already carried a Pocket PC Phone Edition device that could browse the internet, had email, phone, SMS, and so on. There were other precursors even earlier.

I'm not trying to explain away excellence of execution. These companies succeeded for a variety of reasons, including that they were good at what they were doing. Lots of companies, however, are good at what they are doing, and still they fail. Being at the right place at the right time matters. Once in a while, a company finds itself in such favourable circumstances that success is served on a silver platter. While good execution is important, it doesn't explain the magnitude of the success.

Bad execution is likely to eliminate you in the long run, but it doesn't follow logically that good execution guarantees success.

Perhaps the successful companies succeeded because of circumstances, and despite mediocre execution. As usual, you should be wary not to mistake correlation for causation.

Legacy code #

You should be sceptical of adopting processes or technology just because a Big Tech company uses it. Still, if that was all I had in mind, I could probably had said that shorter. I have another point to make.

I often encounter resistance to ideas about better software development on the grounds that the status quo is good enough. Put bluntly,

""legacy," [...] is condescending-engineer-speak for "actually makes money.""

To be clear, I have nothing against the author or the cited article, which discusses something (right-sizing VMs) that I know nothing about. The phrase, or variations thereof, however, is such a fit meme that it spreads. It strongly indicates that people who discuss code quality are wankers, while 'real programmers' produce code that makes money. I consider that a false dichotomy.

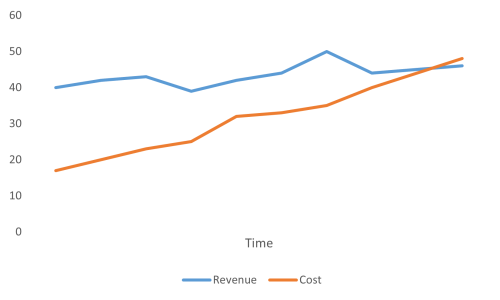

Most software organisations aren't in the fortunate situation that revenues are orders of magnitude greater than costs. Most software organisations can make a decent profit if they find a market and execute on a good idea. Perhaps the revenue starts at 'only' double the cost.

If you can consistently make the double of your costs, you'll be in business for a long time. As the above line chart indicates, however, is that if the costs rise faster than the revenue, you'll eventually hit a point when you start losing money.

The Big Tech companies aren't likely to run into that situation because their profit margins are so great, but normal companies are very much at risk.

The area between the revenue and the cost represents the profit. Thus, looking back, it may be true that a software system has been making money. This doesn't mean, however, that it will keep making money.

In the above chart, the cost eventually exceeds the revenue. If this cost is mainly driven by rising software development costs, then the company is in deep trouble.

I've worked with such a company. When I started with it, it was a thriving company with many employees, most of them developers or IT professionals. In the previous decade, it had turned a nice profit every year.

This all started to change around the time that I arrived. (I will, again, remind the reader that correlation does not imply causation.) One reason I was engaged was that the developers were stuck. Due to external market pressures they had to deliver a tremendous amount of new features, and they were stuck in analysis paralysis.

I helped them get unstuck, but as we started working on the new features, we discovered the size of the mess of the legacy code base.

I recall a conversation I later had with the CEO. He told me, after having discussed the situation with several key people: "I knew that we had a legacy code base... but I didn't know it was this bad!"

Revenue remained constant, but costs kept rising. Today, the company is no longer around.

This was a 100% digital service company. All revenue was ultimately based on software. The business idea was good, but the company couldn't keep up with competitors. As far as I can tell, it was undone by its legacy code base.

Conclusion #

Software should provide some kind of value. Usually profits, but sometimes savings, and occasionally wider concerns are in scope. It's reasonable and professional to consider value as you produce software. You should, however, be aware of a too myopic focus on immediate and past value.

Finding safety in past value is indulging in complacency. Legacy software can make money from day one, but that doesn't mean that it'll keep making money. The main problem with legacy code is that costs keep rising. When non-technical business stakeholders start to notice this, it may be too late.

The is one of many reasons I believe that we, software developers, have a responsibility to combat the mess. I don't think there's anything condescending about that attitude.