Zookeepers must become Rangers by Mark Seemann

For want of a nail the shoe was lost... This post explains why Zookeeper developers must become Ranger developers to escape the vicious cycle of impossible deadlines and low-quality code.

In a previous article I wrote about Ranger and Zookeper developers. The current article is going to make no sense to you if you haven't read the previous, but in brief, Rangers explicitly deal with versioning and forwards and backwards compatibility (henceforth called temporal compatibility) in order to produce workable code.

While reading the previous article, you may have thought that you'd rather like to be a Ranger than a Zookeeper, simply because it sounds cooler. Well, I didn't pick those names by accident :) You don't want to be a Zookeeper developer.

Zookeepers may be under the impression that, since they (or their organization) control the entire installation base of their code, they don't need to deal with the versioning aspect of software design. This is an illusion. It may seem like a little thing, but, through a chain reaction, the lack of versioning leads to impossible deadlines, slipping code quality, death marches and many unpleasant aspects of our otherwise wonderful vocation.

In order to escape the vicious cycle of low-quality-code, death marches, and firefighting, Zookeepers need to explicitly deal with versioning of the software they produce, essentially turning themselves into Rangers.

In the following, I will make two assumptions about the type of software I discuss here:

- It's impossible to predict all future feature requirements.

- Applications don't exist in a vacuum. They depend on other applications, and other applications depend on them.

For the vast majority of Zoo Software, I believe these tenets to be true.

In order to understand why versioning is so important (even for Zoo Software) it's important to first understand why Zookeepers consistently disregard it.

We don't need no steenking design guidelines #

It's sometimes a bit surprising to me that (.NET) programmers are resistant to good design. There's this tome of knowledge originally published as the Framework Design Guidelines and later published online on MSDN as the Design Guidelines for Developing Class Libraries. Even if you don't care to read through it all, tools such as Visual Studio Code Analysis and FxCop (which is free) encapsulate many of those guidelines and helps identify when your code diverges.

In my experience, Zookeeper resistance against the Framework Design Guidelines is perfectly examplified by the 'rules' related to selecting between classes and interfaces:

- Do favor defining classes over interfaces.

- Do use abstract (MustInherit in Visual Basic) classes instead of interfaces to decouple the contract from implementations.

(For the record, I think this is horrible advice, but that's a discussion for another day.)

The problem with a guideline like this is that most Zookeepers react to such advice by thinking: "This isn't relevant for the kind of code I write. I control the entire install base of my code, so it's not a problem for me to introduce a breaking change. That entire knowledge base of design guidelines is targeted at another type of developers. I need not care about it."

Zookeepers fail to address versioning and temporal compatibility because they (incorrectly) assume that they can always schedule deployments of services and clients together in such a way that breaking changes never actually break anything. That may work as long as systems are monolithic and exist in a vacuum, but as soon as you start integrating systems, this disregard for versioning leads straight to hell.

Example: an internal music catalog service #

Now that you understand why Zookeepers tend to ignore versioning it's time to understand where that attitude leads. This is best done with an example.

Imagine a team tasked with building a music catalog service for internal use. In the first release of the service a track looks like this:

<track> <name>Recovery</name> <artist>Curve</artist> <album>Come Clean</album> <length>288</length> </track>

This is obviously a naïve attempt, and a bit of planning could probably have prevented the following nasty particular surprise. However, this is just an illustrative example, and I'm sure you've found yourself in a situation where a new requirement took you entirely by surprise - no matter how much you tried to predict the future.

After the team has released the first version of the music catalog service, it turns out that some tracks may be the result of collaborations, and thus have multiple artists. The track may also appear in multiple albums (such as compilations or greatest hits collections), or on no album at all. Thus, version 2 of a track will have to look like this:

<track> <name>Under Pressure</name> <artists> <artist>David Bowie</artist> <artist>Queen</artist> </artists> <albums> <album>Hot Space</album> <album>Greatest Hits</album> <album>The Singles: 1969-1993</album> </albums> <length>242</length> </track>

This is obviously a breaking change, but since the team works in an organization where the entire installation base is under control, they work with the Enterprise Architecture team to schedule a release of this breaking change with all their clients.

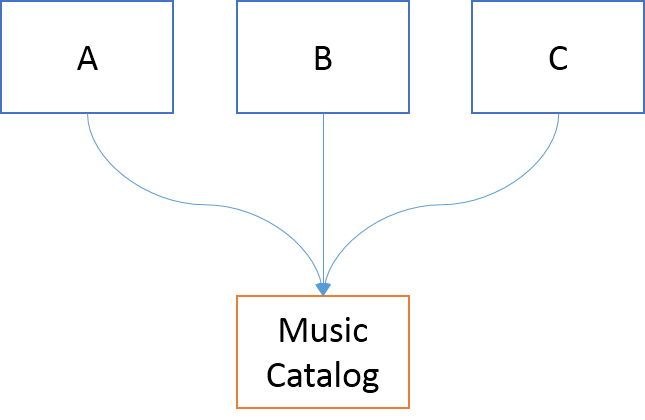

However, the service was made to support other systems, so this change must be coordinated with all the known clients. It turns out that three systems depend on the music catalog service.

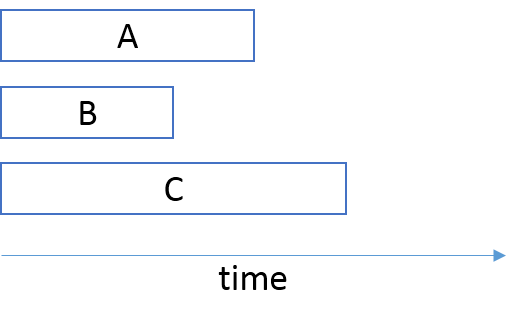

Each of these systems are being worked on by separate teams, each with individual deadlines. These teams are not planning to deploy new versions of their applications all on the same day. Their immediate schedules are already set, and they aren't aligned.

The Architecture team must negotiate future iterations with teams A, B, and C to line them up so that the music catalog team can release their new version on the same day.

This alignment may be months into the future - perhaps a significant fraction of a year. The music catalog team can't sit still while they wait for this date to arrive, so they work on other new features, most likely introducing other breaking changes along the way.

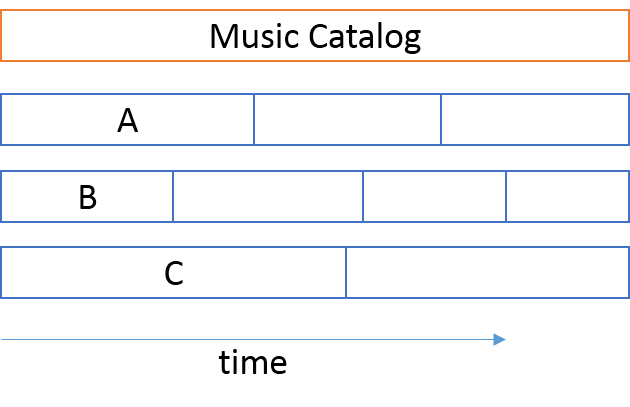

Meanwhile, team A goes through three iterations. In the first two iterations, they know that they are going to deploy into a production environment with version 1 of the music catalog, so they are going to need a testing environment that looks like that. For the third iteration, they know that they are going to deploy into a production environment with version 2 of the music catalog, so they are going to have to change their testing environment to reflect that fact.

Team B goes through four iterations that don't align with those of Team A. When Team A updates their testing environment to music catalog version 2, Team B is still working on an iteration where they must test against version 1. Thus, they must have their own testing environment. They can't share the testing environment with Team A.

The same is true for Team C: it needs its own private testing environment. Notice that this is a testing environment that not only involves configuration and maintenance of the team's own application, but also of its dependency, the music catalog service. In order to provide realistic data for performance testing, each testing environment must also be maintained with representative sample data, and may have to run on production-like hardware, in production-like network topologies. Add software licences to the mix, and you may start to realize that such a testing environment is expensive.

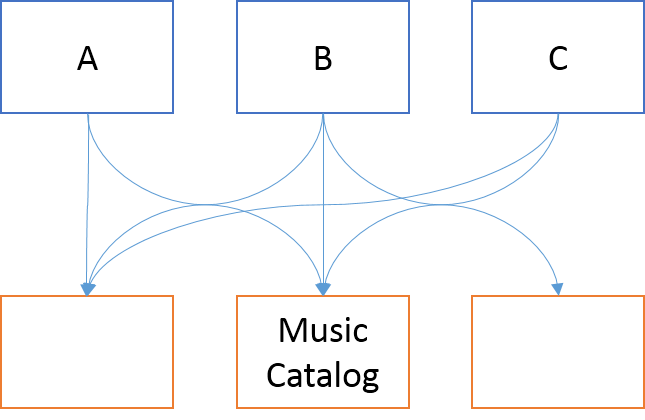

So far, the analysis has been unrealistically simplified. It turns out that the A, B, and C applications have other dependencies besides the music catalog service.

Each of these dependencies are also moving, producing new features. Some of those new features also involve breaking changes. Once again, the Enterprise Architecture team must negotiate a coordinated deployment date to make sure nothing breaks. However, the organization have more applications than A, B, and C. Application D, for instance, doesn't depend on the music catalog service, but it shares a dependency with application A. Thus, Team D must take part in the coordination effort, making sure that they deploy their new version on the same day as everyone else. Meanwhile, they'll need yet another one of those expensive testing environments.

I'm not making this up. I've had clients (financial institutions) that had hundreds of testing environments and big, coordinated deployments. Their applications didn't have two or three dependencies, but dozens of dependencies each - often on mainframe-based systems (very expensive).

The rot of Big Bang Releases #

All this leads to Big Bang Releases. Once or twice each year, all Zoo Sofware is simultaneously deployed according to a meticulously laid plan. This date becomes an unnegotiatable deadline. No team can miss the deadline, because dozens of other teams directly or indirectly depend on each other.

What happens when a Big Bang deadline grows nearer? What if you aren't ready to release? What if you just discovered a catastrophic bug?

This is what happens:

- Teams work nights and weekends to meet deadlines. Members burn out, or get divorced, or decide to quit. More work is left for remaining team members. A vicious circle indeed.

- Software is deployed with known bugs. Often, it's simply not possible to address all bugs in time, because they are discovered too late.

- The team enters survival mode, building up technical debt. Unit tests are ignored. Dirty hacks are made. Code rots. In the end, the team deploys a version of the software where they don't really know what works and what doesn't work. This makes it harder to work on the next version, because the lack of test coverage means that they don't even know if they'll be introducing breaking changes. At the absence of knowledge it's better to assume the worst. Another vicious cycle is created.

Remember: each team must deploy at the Big Bang Release, no matter how bad the quality is. It's not even possible to elect to skip a release all together, because the other teams have built their new versions with the assumption that your application's breaking changes will be deployed. In a Big Bang Release, there are only two options: Deploy everything, or deploy nothing. Deciding to deploy nothing may threaten the entire company's existence, so that decision is rarely made.

Do you think I'm exaggerating? I have seen this happen more than once. In fact, I also strongly suspect that this sort of situation recently unfolded itself within a big international ISV - at least, the symptoms are all here, for all to see :)

All this because Zookeepers don't deal with temporal compatibility.

Call to action #

Zookeepers must stop being Zookeepers and become Rangers. There's no excuse to not deal explicitly with versioning. You can't just introduce a breaking change in your code. The cost is often much larger than you think. The repercussions can be immense. Sometimes there's no way around breaking changes, but deal with them in tried-and-true ways. Introduce your new API side-by-side with the old API and deprecate the old API. Give clients a chance to move to the new API at their own pace. Monitor usage of your API to figure out when it's safe to completely remove the deprecated API. There are many well-described ways to deal with versioning and temporal compatibility. This is not an article about how to evolve an API, but rather a call to action: explicitly address versioning, or face the consequences!

Looser coupling can help. What I've described here is simply a form of tight temporal coupling. Still, even with loosely coupled, asynchronous, messaging-based architectures, messages must still be explicitly versioned to avoid problems.

Once an orginazation has moved entirely to a loosely coupled, explicitly versioned architecture where each team can use Continuous Delivery, they may find that they don't need that Enterprise Achitecture team at all :)

Comments

Thanks for sharing,

Jason

In such a case, one had to change an acceptance test if a service could not deal with legacy clients. A developer who does this or a manager who commands this, acts unprofessional.

A team that calls itself agile and does not use the tools and techniques necessary for agile development, is just a bunch of cowboy coders, but neither "Zookeepers" nor "Rangers".

The point of the article (IMO) is that developers need to learn a new tool that you haven't listed - namely good internal version handling (and to start thinking of internal collaborators in the same way as external).

A tricky thing for an organisation is to decide when make the move from (easy-to-write) temporally coupled code to discrete services (with increased versioning and infrastructure overheads). Most places with this problem have started off small, grow quickly by bolting bits onto the existing architecture, and by the time someone switched on enough to start changing the organisation takes charge, it is too late to make the switch easily. TBH most places I've worked where this is the root cause of the problems, the Enterprise Architect team can't see the wood for the trees.

However, the other Markus is spot on. The message of this article isn't that you should use TDD, Continuous Integration, etc. Lot's of people have already said that before me. The message is that even if you are an 'internal' developer, you must think explicitly about versioning and backwards compatibility.