Library Bundle Facade by Mark Seemann

Some people want to define a Facade for a bundle of libraries. Is that a good idea?

My recent article on Composition Root reuse generated some comments:

These comments are from two different people, but they provide a decent summary of the concerns being voiced."What do you think about pushing these factories and builders to a library so that they can be reused by different composition roots?"

"We want to share the composition root, because otherwise when a component needs a new dependency and a constructor parameter is added, we'd have to change the same code in two different places."

Is it a good idea to provide one or more Facades, for example in the form of Factories or Builders, for the libraries making up a Composition Root? More specifically, is it a good idea to provide a Factory or Builder that can compose a complete object graph spanning multiple libraries?

In this article, I will attempt to answer that question for various cases of library bundles. To make the terminology a bit more streamlined, I'll refer to any Factory or Builder that composes object graphs as a Composer.

Single library #

In the case of a single library, I think I've already answered the question in the affirmative. There's nothing wrong with including a Facade in the form of a Factory or Builder in order to make that single library easier to use.

Two libraries #

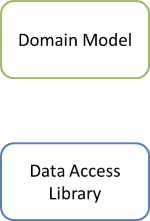

When you introduce a second library, things start becoming interesting. If we consider the case of two libraries, for example a Domain Model and a Data Access Library, the Composition Root will need to compose an object graph where some of the objects in the graph are from the Domain Model, and some of the objects are from the Data Access Library.

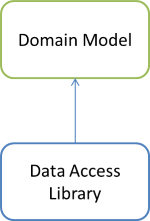

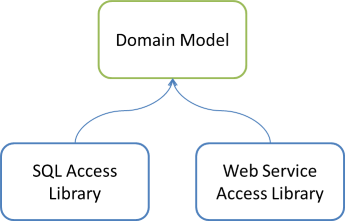

In the spirit of Agile Principles, Patterns, and Practices (APPP), it turns out that simply drawing dependency diagrams can be helpful. From the Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) we know that the "clients [...] own the abstract interfaces" (APPP, chapter 11), which means that for our two example libraries, the dependency graph must look like this:

At least, if you follow the most common architectures for loosely couple code, the Domain Model is the 'client', so it gets to define the interfaces it needs. Thus, it follows that the Data Access Library, in order to implement those interfaces, must have a compile-time dependency on the Domain Model. That's what the arrow means.

From this diagram, it should be clear that you can't put a Factory or Builder in the Domain Model library. If the Composer should compose object graphs from both libraries, it would need to reference both of those libraries, and the Domain Model can't reference the Data Access Library, since that would result in a circular reference.

You could put the Composer in the Data Access Library, but that somehow doesn't feel right, and in any case, as we shall see later, this solution can't be generalised to n libraries.

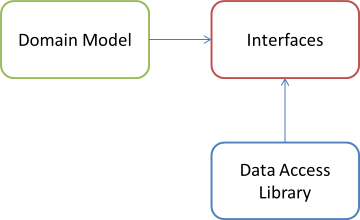

A solution that many people reach for, then, is to pull the interfaces out into a separate library, like this:

It's a bit like cheating, according to the DIP, but it's as decoupled as before. In this diagram, the Domain Model depends on the interfaces because it uses them, while the Data Access Library depends on the interface library because it implements the interfaces. Unfortunately, this doesn't solve the problem at all, because there's still no place to place a Composer without getting into a problem with either the DIP, or circular references (exercise: try it!).

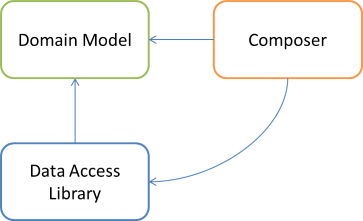

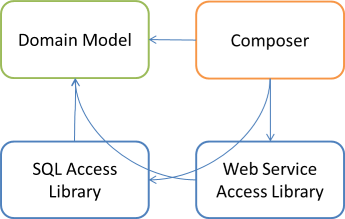

A possible option is to keep the libraries as the DIP dictates, and then add a third Composer library:

The Composer library references both the Domain Model and the Data Access Library, so it's possible for it to compose object graphs with objects from both libraries. The only purpose of this library, then, is to compose those object graphs, so it'll likely only contain a single class.

Multiple libraries #

Does the above conclusions change if you have more than two libraries? Only in the sense that it further restricts your options. As the analysis of the special case with two libraries demonstrated, you only have two options for adding a Composer to your bundle of libraries:

- Put the Composer in the Data Access Library

- Put the Composer in a new dedicated library

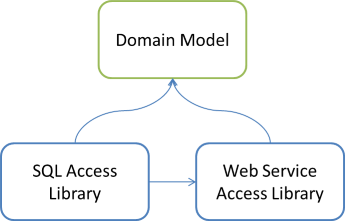

Imagine that you have two Data Access Libraries instead of one:

For instance, the SQL Access Library may implement various interfaces defined by the Domain Model, based on a SQL Server database; and the Web Service Access Library may implement some other interfaces by calling out to some web service.

If the Composer must be able to compose object graphs with object from all three libraries, it must reside in a library that references all of the relevant libraries. The Domain Model is still out of the question because you can't have circular references. That leaves one of the two Data Access libraries. It'd be technically possible to e.g. add a reference from the SQL Access Library to the Web Service Access Library, and put the Composer in the SQL Access Library:

However, why would you ever do that? It's clearly wrong to let one Data Access library depend on another, and it doesn't help if you reverse the arrow.

Thus, the only option left is to add a new Composer library:

As before, the Composer library has references to all other libraries, and contains a single class that composes object graphs.

Over-engineering #

The point of this analysis is to arrive at the conclusion that no matter how you twist and turn, you'll have to add a completely new library with the only purpose of composing object graphs. Is it warranted?

If the only motivation for doing this is to avoid duplicated code, I would argue that this looks like over-engineering. In the questions quoted above, it sounds as if the Rule of Three isn't even satisfied. It's always important to question your motivations for avoiding duplication. In this case, I'd be wary of introducing so much extra complexity only in order to avoid writing the same lines of code twice - particularly when it's likely that the duplication is accidental.

TL;DR #

Attempting to provide a reusable Facade to compose object graphs across multiple libraries is hardly worth the trouble. Think twice before you do it.

Comments

Dear Mark,

Thanks again for another wonderful post. I'm one of the guys you mentioned at the beginning of this text and I totally agree with you on this subject.

Maybe I wasn't specific enough in my comment that I didn't mean to introduce factories and builders handling dependencies from two or more assemblies, but only from a single one. The composition root wires the independent subgraphs from the different assemblies together.

However, I want to reemphasize the Builder Pattern in this context: it provides default dependencies for the object graph to be created and (usually) a fluent API (i.e. some sort of method chaining) to exchange these dependencies. This has the following consequences for the client programmer using the builder(s): he or she can easily create a default object graph by calling new Builder().Build() and still exchange dependencies he or she cares about. This can keep the composition root clean (at least for Arrange phases of tests this is true).

Why I'm so excited about this? Because I use this all the time in my automated tests, but haven't really used it in my production composition roots (or seen it in others). After reading this post and Composition Root Reuse, I will try to incorporate builders more often in my production code.

Mark - thank you for making me think about this.

Kenny, thank you for writing. The Builder pattern is indeed a good way to implement Facades for a single library.