Pure times in F# by Mark Seemann

A Polling Consumer implementation written in F#.

Previously, you saw how to implement a Polling Consumer in Haskell. This proves that it's possible to write pure functional code modelling long-running interactions with the (impure) world. In this article, you'll see how to port the Haskell code to F#.

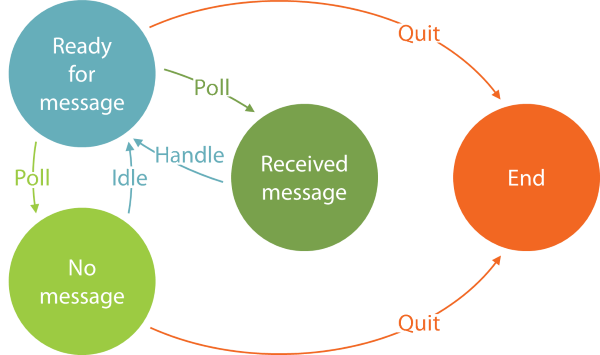

For reference, I'll repeat the state transition diagram here:

For a complete description of the goals and constraints of this particular Polling Consumer implementation, see my earlier Type Driven Development article, or, even better, watch my Pluralsight course Type-Driven Development with F#.

State data types #

The program has to keep track of various durations. You can model these as naked TimeSpan values, but in order to add extra type safety, you can, instead, define them as separate types:

type PollDuration = PollDuration of TimeSpan type IdleDuration = IdleDuration of TimeSpan type HandleDuration = HandleDuration of TimeSpan type CycleDuration = { PollDuration : PollDuration HandleDuration : HandleDuration }

This is a straightforward port of the Haskell code. See the previous article for more details about the motivation for doing this.

You can now define the states of the finite state machine:

type State<'msg> = | ReadyState of CycleDuration list | ReceivedMessageState of (CycleDuration list * PollDuration * 'msg) | NoMessageState of (CycleDuration list * PollDuration) | StoppedState of CycleDuration list

Again, this is a straight port of the Haskell code.

From instruction set to syntactic sugar #

The Polling Consumer must interact with its environment in various ways:

- Query the system clock

- Poll for messages

- Handle messages

- Idle

type PollingInstruction<'msg, 'next> = | CurrentTime of (DateTimeOffset -> 'next) | Poll of (('msg option * PollDuration) -> 'next) | Handle of ('msg * (HandleDuration -> 'next)) | Idle of (IdleDuration * (IdleDuration -> 'next))

Once more, this is a direct translation of the Haskell code, but from here, this is where your F# code will have to deviate from Haskell. In Haskell, you can, with a single line of code, declare that such a type is a functor. This isn't possible in F#. Instead, you have to explicitly write a map function. This isn't difficult, though. There's a reason that the Haskell compiler can automate this:

// ('a -> 'b) -> PollingInstruction<'c,'a> -> PollingInstruction<'c,'b> let private mapI f = function | CurrentTime next -> CurrentTime (next >> f) | Poll next -> Poll (next >> f) | Handle (x, next) -> Handle (x, next >> f) | Idle (x, next) -> Idle (x, next >> f)

The function is named mapI, where the I stands for instruction. It's private because the next step is to package the functor in a monad. From that monad, you can define a new functor, so in order to prevent any confusion, I decided to hide the underlying functor from any consumers of the API.

Defining a map function for a generic type like PollingInstruction<'msg, 'next> is well-defined. Pattern-match each union case and return the same case, but with the next function composed with the input function argument f: next >> f. In later articles, you'll see more examples, and you'll see how this recipe is entirely repeatable and automatable.

While a functor isn't an explicit concept in F#, this is how PollingInstruction msg next is a Functor in Haskell. Given a functor, you can produce a free monad. The reason you'd want to do this is that once you have a monad, you can get syntactic sugar. Currently, PollingInstruction<'msg, 'next> only enables you to create Abstract Syntax Trees (ASTs), but the programming experience would be cumbersome and alien. Monads give you automatic do notation in Haskell; in F#, it enables you to write a computation expression builder.

Haskell's type system enables you to make a monad from a functor with a one-liner: type PollingProgram msg = Free (PollingInstruction msg). In F#, you'll have to write some boilerplate code. First, you have to define the monadic type:

type PollingProgram<'msg, 'next> = | Free of PollingInstruction<'msg, PollingProgram<'msg, 'next>> | Pure of 'next

You already saw a hint of such a type in the previous article. The PollingProgram<'msg, 'next> discriminated union defines two cases: Free and Pure. The Free case is a PollingInstruction that produces a new PollingProgram as its next step. In essence, this enables you to build an AST, but you also need a signal to stop and return a value from the AST. That's the purpose of the Pure case.

Such a type is only a monad if it defines a bind function (that obey the monad laws):

// ('a -> PollingProgram<'b,'c>) -> PollingProgram<'b,'a> // -> PollingProgram<'b,'c> let rec bind f = function | Free instruction -> instruction |> mapI (bind f) |> Free | Pure x -> f x

This bind function pattern-matches on Free and Pure, respectively. In the Pure case, it simply uses the underlying result value x as an input argument to f. In the Free case, it composes the underlying functor (mapI) with itself recursively. If you find this step obscure, I will not blame you. Just like the implementation of mapI is a bit of boilerplate code, then so is this. It always seems to work this way. If you want to dig deeper into the inner workings of this, then Scott Wlaschin has a detailed explanation.

With the addition of bind PollingProgram<'msg, 'next> becomes a monad (I'm not going to show that the monad laws hold, but they do). Making it a functor is trivial:

// ('a -> 'b) -> PollingProgram<'c,'a> -> PollingProgram<'c,'b> let map f = bind (f >> Pure)

The underlying PollingInstruction type was already a functor. This function makes PollingProgram a functor as well.

It'll be convenient with some functions that lifts each PollingInstruction case to a corresponding PollingProgram value. In Haskell, you can use the liftF function for this, but in F# you'll have to be slightly more explicit:

// PollingProgram<'a,DateTimeOffset> let currentTime = Free (CurrentTime Pure) // PollingProgram<'a,('a option * PollDuration)> let poll = Free (Poll Pure) // 'a -> PollingProgram<'a,HandleDuration> let handle msg = Free (Handle (msg, Pure)) // IdleDuration -> PollingProgram<'a,IdleDuration> let idle duration = Free (Idle (duration, Pure))

currentTime and poll aren't even functions, but values. They are, however, small PollingProgram values, so while they look like values (as contrasted to functions), they represent singular executable instructions.

handle and idle are both functions that return PollingProgram values.

You can now implement a small computation expression builder:

type PollingBuilder () = member this.Bind (x, f) = Polling.bind f x member this.Return x = Pure x member this.ReturnFrom x = x member this.Zero () = this.Return ()

As you can tell, not much is going on here. The Bind method simply delegates to the above bind function, and the rest are trivial one-liners.

You can create an instance of the PollingBuilder class so that you can write PollingPrograms with syntactic sugar:

let polling = PollingBuilder ()

This enables you to write polling computation expressions. You'll see examples of this shortly.

Most of the code you've seen here is automated in Haskell. This means that while you'll have to explicitly write it in F#, it follows a recipe. Once you get the hang of it, it doesn't take much time. The maintenance overhead of the code is also minimal, because you're essentially implementing a universal abstraction. It's not going to change.

Support functions #

Continuing the port of the previous article's Haskell code, you can write a pair of support functions. These are small PollingProgram values:

// IdleDuration -> DateTimeOffset -> PollingProgram<'a,bool> let private shouldIdle (IdleDuration d) stopBefore = polling { let! now = Polling.currentTime return now + d < stopBefore }

This shouldIdle function uses the polling computation expression defined above. It first uses the above Polling.currentTime value to get the current time. While Polling.currentTime is a value of the type PollingProgram<'b,DateTimeOffset>, the let! binding makes now a simple DateTimeOffset value. Computation expressions give you the same sort of syntactic sugar that do notation does in Haskell.

If you add now to d, you get a new DateTimeOffset value that represents the time that the program will resume, if it decides to suspend itself for the idle duration. If this time is before stopBefore, the return value is true; otherwise, it's false. Similar to the Haskell example, the return value of shouldIdle isn't just bool, but rather PollingProgram<'a,bool>, because it all takes place inside the polling computation expression.

The function looks impure, but it is pure.

In the same vein, you can implement a shouldPoll function:

// CycleDuration -> TimeSpan let toTotalCycleTimeSpan x = let (PollDuration pd) = x.PollDuration let (HandleDuration hd) = x.HandleDuration pd + hd // TimeSpan -> DateTimeOffset -> CycleDuration list -> PollingProgram<'a,bool> let private shouldPoll estimatedDuration stopBefore statistics = polling { let expectedHandleDuration = statistics |> List.map toTotalCycleTimeSpan |> Statistics.calculateExpectedDuration estimatedDuration let! now = Polling.currentTime return now + expectedHandleDuration < stopBefore }

This function uses two helper functions: toTotalCycleTimeSpan and Statistics.calculateExpectedDuration. I've included toTotalCycleTimeSpan in the code shown here, while I'm skipping Statistics.calculateExpectedDuration, because it hasn't changed since the code I show in my Pluralsight course. You can also see the function in the GitHub repository accompanying this article.

Compared to shouldIdle, the shouldPoll function needs an extra (pure) step in order to figure out the expectedHandleDuration, but from there, the two functions are similar.

Transitions #

All building blocks are now ready for the finite state machine. In order to break the problem into manageable pieces, you can write a function for each state. Such a function should take as input the data associated with a particular state, and return the next state, based on the input.

The simplest transition is when the program reaches the end state, because there's no way out of that state:

// CycleDuration list -> PollingProgram<'a,State<'b>> let transitionFromStopped s = polling { return StoppedState s }

The data contained in a StoppedState case has the type CycleDuration list, so the transitionFromStopped function simply lifts such a list to a PollingProgram value by returning a StoppedState value from within a polling computation expression.

Slightly more complex, but still simple, is the transition out of the received state. There's no branching logic involved. You just have to handle the message, measure how much time it takes, append the measurements to previous statistics, and return to the ready state:

// CycleDuration list * PollDuration * 'a -> PollingProgram<'a,State<'b>> let transitionFromReceived (statistics, pd, msg) = polling { let! hd = Polling.handle msg return { PollDuration = pd; HandleDuration = hd } :: statistics |> ReadyState }

This function uses the Polling.handle convenience function to handle the input message. Although the handle function returns a PollingProgram<'a,HandleDuration> value, the let! binding inside of a polling computation expression makes hd a HandleDuration value.

The data contained within a ReceivedMessageState case is a CycleDuration list * PollDuration * 'msg tuple. That's the input argument to the transitionFromReceived function, which immediately pattern-matches the tuple's three elements into statistics, pd, and msg.

The pd element is the PollDuration - i.e. the time it took to reach the received state. The hd value returned by Polling.handle gives you the time it took to handle the message. From those two values you can create a new CycleDuration value, and cons (::) it onto the previous statistics. This returns an updated list of statistics that you can pipe to the ReadyState case constructor.

ReadyState in itself creates a new State<'msg> value, but since all of this takes place inside a polling computation expression, the return type of the function becomes PollingProgram<'a,State<'b>>.

The transitionFromReceived function handles the state when the program has received a message, but you also need to handle the state when no message was received:

// IdleDuration -> DateTimeOffset -> CycleDuration list * 'a // -> PollingProgram<'b,State<'c>> let transitionFromNoMessage d stopBefore (statistics, _) = polling { let! b = shouldIdle d stopBefore if b then do! Polling.idle d |> Polling.map ignore return ReadyState statistics else return StoppedState statistics }

This function first calls the shouldIdle support function. Similar to Haskell, you can see how you can compose larger PollingPrograms from smaller PollingProgram values - just like you can compose 'normal' functions from smaller functions.

With the syntactic sugar in place, b is simply a bool value that you can use in a standard if/then/else expression. If b is false, then return a StoppedState value; otherwise, continue with the next steps.

Polling.idle returns the duration of the suspension, but you don't actually need this data, so you can ignore it. When Polling.idle returns, you can return a ReadyState value.

It may look as though that do! expression is a blocking call, but it really isn't. The transitionFromNoMessage function only builds an Abstract Syntax Tree, where one of the instructions suggests that an interpreter could block. Unless evaluated by an impure interpreter, transitionFromNoMessage is pure.

The final transition is the most complex, because there are three possible outcomes:

// TimeSpan -> DateTimeOffset -> CycleDuration list // -> PollingProgram<'a,State<'a>> let transitionFromReady estimatedDuration stopBefore statistics = polling { let! b = shouldPoll estimatedDuration stopBefore statistics if b then let! pollResult = Polling.poll match pollResult with | Some msg, pd -> return ReceivedMessageState (statistics, pd, msg) | None, pd -> return NoMessageState (statistics, pd) else return StoppedState statistics }

In the same way that transitionFromNoMessage uses shouldIdle, the transitionFromReady function uses the shouldPoll support function to decide whether or not to keep going. If b is false, it returns a StoppedState value.

Otherwise, it goes on to poll. Thanks to all the syntactic sugar, pollResult is an 'a option * PollDuration value. As always, when you have a discriminated union, you can handle all cases with pattern matching (and the compiler will help you keep track of whether or not you've handled all of them).

In the Some case, you have a message, and the duration it took to poll for that message. This is all the data you need to return a ReceivedMessageState value.

In the None case, you also have the poll duration pd; return a NoMessageState value.

That's four transition functions that you can combine in a single function that, for any state, returns a new state:

// TimeSpan -> IdleDuration -> DateTimeOffset -> State<'a> // -> PollingProgram<'a,State<'a>> let transition estimatedDuration idleDuration stopBefore = function | ReadyState s -> transitionFromReady estimatedDuration stopBefore s | ReceivedMessageState s -> transitionFromReceived s | NoMessageState s -> transitionFromNoMessage idleDuration stopBefore s | StoppedState s -> transitionFromStopped s

You simply pattern-match the (implicit) input argument with the four state cases, and call the appropriate transition function for each case.

Interpretation #

The transition function is pure. It returns a PollingProgram value. How do you turn it into something that performs real work?

You write an interpreter:

// PollingProgram<Msg,'a> -> 'a let rec interpret = function | Pure x -> x | Free (CurrentTime next) -> DateTimeOffset.Now |> next |> interpret | Free (Poll next) -> Imp.poll () |> next |> interpret | Free (Handle (msg, next)) -> Imp.handle msg |> next |> interpret | Free (Idle (d, next)) -> Imp.idle d |> next |> interpret

A PollingProgram is either a Pure or a Free case. In the Free case, the contained data is a PollingInstruction value, which can be one of four separate cases. With pattern matching, the interpreter handles all five cases.

In the Pure case, it returns the value, but in all the Free cases, it recursively calls itself after having first followed the instruction in each PollingInstruction case. For instance, when the instruction is CurrentTime, it invokes DateTimeOffset.Now, passes the return value (a DateTimeOffset value) to the next continuation, and then recursively calls interpret. The next instruction, then, could be another Free case, or it could be Pure.

The other three instruction cases delegate to implementation functions defined in an Imp module. I'm not going to show them here. They're normal, although impure, F# functions.

Execution #

You're almost done. You have a function that returns a new state for any given input state, as well as an interpreter. You need a function that can repeat this in a loop until it reaches StoppedState:

// TimeSpan -> IdleDuration -> DateTimeOffset -> State<Msg> -> State<Msg> let rec run estimatedDuration idleDuration stopBefore s = let ns = PollingConsumer.transition estimatedDuration idleDuration stopBefore s |> interpret match ns with | PollingConsumer.StoppedState _ -> ns | _ -> run estimatedDuration idleDuration stopBefore ns

This function calls PollingConsumer.transition with the input state s, which returns a new PollingProgram<Msg,PollingConsumer.State<Msg>> value that you can pipe to the interpret function. That gives you the new state ns. If ns is a StoppedState, you return; otherwise, you recurse into run for another round.

Finally, you can write the entry point for the application:

[<EntryPoint>] let main _ = let timeAtEntry = DateTimeOffset.Now printOnEntry timeAtEntry let stopBefore = timeAtEntry + limit let estimatedDuration = TimeSpan.FromSeconds 2. let idleDuration = TimeSpan.FromSeconds 5. |> IdleDuration let durations = PollingConsumer.ReadyState [] |> run estimatedDuration idleDuration stopBefore |> PollingConsumer.durations |> List.map PollingConsumer.toTotalCycleTimeSpan printOnExit timeAtEntry durations // Return 0. This indicates success. 0

This defines an estimated duration of 2 seconds, an idle duration of 5 seconds, and a maximum run time of 60 seconds (limit). The initial state is ReadyState with no prior statistics. Pass all these arguments to the run function, and you have a running program.

This function also uses a few printout functions that I'm not going to show here. When you run the program, you should see output like this:

Started polling at 11:18:28. Polling Handling Polling Handling Polling Sleeping Polling Sleeping Polling Handling Polling Handling Polling Sleeping Polling Sleeping Polling Sleeping Polling Handling Polling Sleeping Polling Sleeping Polling Sleeping Polling Sleeping Polling Handling Stopped polling at 11:19:26. Elapsed time: 00:00:58.4428980. Handled 6 message(s). Average duration: 00:00:01.0550346 Standard deviation: 00:00:00.3970599

It does, indeed, exit before 60 seconds have elapsed.

Summary #

You can model long-running interactions with an Abstract Syntax Tree. Without computation expressions, writing programs as 'raw' ASTs would be cumbersome, but turning the AST into a (free) monad makes it all quite palatable.

Haskell code with a free monad can be ported to F#, although some boilerplate code is required. That code, however, is unlikely to be much of a burden, because it follows a well-known recipe that implements a universal abstraction.

For more details on how to write free monads in F#, see Pure interactions.