Convex hull monoid by Mark Seemann

The union of convex hulls form a monoid. Yet another non-trivial monoid example, this time in F#.

This article is part of a series about monoids. In short, a monoid is an associative binary operation with a neutral element (also known as identity).

If you're reading the series as an object-oriented programmer, I apologise for the digression, but this article exclusively contains F# code. The next article will return with more C# examples.

Convex hull #

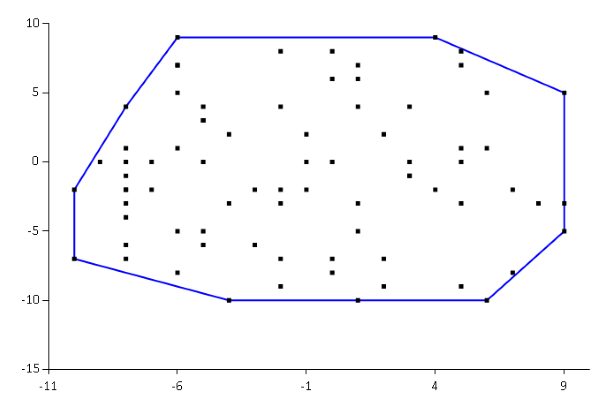

In a past article I've described my adventures with finding convex hulls in F#. The convex hulls I've been looking at form the external convex boundary of a set of two-dimensional points. While you can generalise the concept of convex hulls to n dimensions, we're going to stick to two-dimensional hulls here.

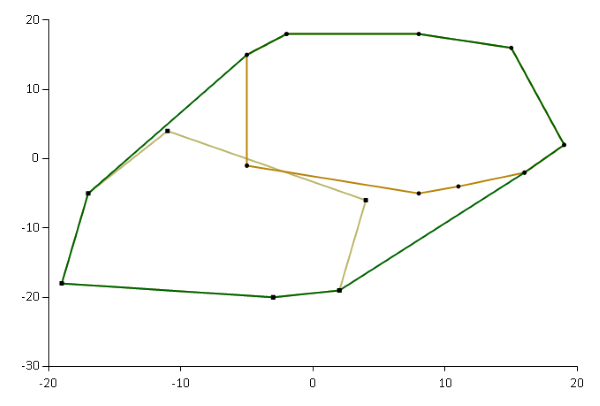

If you have two convex hulls, you can find the convex hull of both:

Here, the dark green outline is the convex hull of the two lighter-coloured hulls.

Finding the convex hull of two other hulls is a binary operation. Is it a monoid?

In order to examine that, I'm going to make some changes to my existing code base, the most important of which is that I'm going to introduce a Hull type. The intent is that if points are contained within this type, then only the convex hull remains. It'd be better if it was possible to make the

case constructor private, but if one does that, then the hull function can no longer be inlined and generic.

type Hull<'a> = Hull of ('a * 'a) list

With the addition of the Hull type, you can now add a binary operation:

// Hull<'a> -> Hull<'a> -> Hull<'a> let inline (+) (Hull x) (Hull y) = hull (x @ y)

This operation explicitly uses the + operator, so I'm clearly anticipating the turn of events here. Nothing much is going on, though. The function pattern-matches the points out of two Hull values. x and y are two lists of points. The + function concatenates the two lists with the @ operator, and finds the convex hull of this new list of points.

Associativity #

My choice of operator strongly suggests that the + operation is a monoid. If you have three hulls, the order in which you find the hulls doesn't matter. One way to demonstrate that property is with property-based testing. In this article, I'm using Hedgehog.

[<Fact>] let ``Hull addition is associative`` () = Property.check <| property { let! (x, y, z) = Range.linear -10000 10000 |> Gen.int |> Gen.tuple |> Gen.list (Range.linear 0 100) |> Gen.tuple3 (hull x + hull y) + hull z =! hull x + (hull y + hull z) }

This automated test generates three lists of points, x, y, and z. The hull function uses the Graham Scan algorithm to find the hull, and part of that algorithm includes calculating the cross product of three points. For large enough integers, the cross product will overflow, so the property constrains the point coordinates to stay within -10,000 and 10,000. The implication of that is that although + is associative, it's only associative for a subset of all 32-bit integers. I could probably change the internal implementation so that it calculates the cross product using bigint, but I'll leave that as an exercise to you.

For performance reasons, I also arbitrarily decided to constrain the size of each set of points to between 0 and 100 elements. If I change the maximum count to 1,000, it takes my laptop 9 seconds to run the test.

In addition to Hedgehog, this test also uses xUnit.net, and Unquote for assertions. The =! operator is the Unquote way of saying must equal. It's an assertion.

This property passes, which demonstrates that the + operator for convex hulls is associative.

Identity #

Likewise, you can write a property-based test that demonstrates that an identity element exists for the + operator:

[<Fact>] let `` Hull addition has identity`` () = Property.check <| property { let! x = Range.linear -10000 10000 |> Gen.int |> Gen.tuple |> Gen.list (Range.linear 0 100) let hasIdentity = Hull.identity + hull x = hull x + Hull.identity && hull x + Hull.identity = hull x test <@ hasIdentity @> }

This test generates a list of integer pairs (x) and applies the + operator to x and Hull.identity. The test passes for all x that Hedgehog generates.

What's Hull.identity?

It's simply the empty hull:

module Hull = let identity = Hull []

If you have a set of zero 2D points, then the convex hull is empty as well.

The + operator for convex hulls is a monoid for the set of coordinates where the cross product doesn't overflow.

Summary #

If you consider that the Hull type is nothing but a container for a list, it should come as no surprise that a monoid exists. After all, list concatenation is a monoid, and the + operator shown here is a combination of list concatenation (@) and a Graham Scan.

The point of this article was mostly to demonstrate that monoids exist not only for primitive types, but also for (some) more complex types. The + operator shown here is really a set union operation. What about intersections of convex hulls? Is that a monoid as well? I'll leave that as an exercise.

Next: Tuple monoids.

Comments

Is that true that you could replace hull with any other function, and (+) operator would still be a monoid? Since the operator is based on list concatenation, the "monoidness" is probably derived from there, not from function implementation.

Mikhail, thank you for writing. You can't replace

hullwith any other function and expect list concatenation to remain a monoid. I'm sorry if my turn of phrase gave that impression. I can see how one could interpret my summary in that way, but it wasn't my intention to imply that this relationship holds in general. It doesn't, and it's not hard to show, because we only need to come up with a single counter-example.One counter example is a function that always removes the first element in a list - unless the list is empty, in which case it simply returns the empty list. In Haskell, we can define a

newtypewith this behaviour in mind:For my own convenience, I wrote the entire counter-example in GHCi (the Haskell REPL), but imagine that the

Drop1data constructor is hidden from clients. The normal way to do that is to not export the data constructor from the module. In GHCi, we can't do that, but just pretend that theDrop1data constructor is unavailable to clients. Instead, we'll have to use this function:The

drop1function has the type[a] -> Drop1 a; it takes a list, and returns aDrop1value, which contains the input list, apart from its first element.We can attempt to make

Drop 1a monoid:Prelude Data.Monoid Data.List> :{ Prelude Data.Monoid Data.List| instance Monoid (Drop1 a) where Prelude Data.Monoid Data.List| mempty = drop1 [] Prelude Data.Monoid Data.List| mappend (Drop1 xs) (Drop1 ys) = drop1 (xs ++ ys) Prelude Data.Monoid Data.List| :}Hopefully, you can see that the implementation of

mappendis similar to the above F# implementation of+for convex hulls. In F#, the list concatenation operator is@, whereas in Haskell, it's++.This compiles, but it's easy to come up with some counter-examples that demonstrate that the monoid laws don't hold. First, associativity:

(The

<>operator is an infix alias formappend.)Clearly,

[5,6,8,9]is different from[3,6,8,9], so the operation isn't associative.Equivalently, identity fails as well:

Again,

[3]is different from[2,3], somemptyisn't a proper identity element.It was easy to come up with this counter-example. I haven't attempted to come up with more, but I'd be surprised if I accidentally happened to pick the only counter-example there is. Rather, I conjecture that there are infinitely many counter-examples that each proves that there's no general rule about 'wrapped' lists operations being monoids.