Asynchronous functors by Mark Seemann

Asynchronous computations form functors. An article for object-oriented programmers.

This article is an instalment in an article series about functors. The previous article covered the Lazy functor. In this article, you'll learn about closely related functors: .NET Tasks and F# asynchronous workflows.

A word of warning is in order. .NET Tasks aren't referentially transparent, whereas F# asynchronous computations are. You could argue, then, that .NET Tasks aren't proper functors, but you mostly observe the difference when you perform impure operations. As a general observation, when impure operations are allowed, the conclusions of this overall article series are precarious. We can't radically change how the .NET languages work, so we'll have to soldier on, pretending that impure operations are delegated to other parts of our system. Under this undue assumption, we can pretend that Task<T> forms a functor.

Task functor #

You can write an idiomatic Select extension method for Task<T> like this:

public async static Task<TResult> Select<T, TResult>( this Task<T> source, Func<T, TResult> selector) { var x = await source; return selector(x); }

With this extension method in scope, you can compose asynchronous computations like this:

Task<int> x = // ... Task<string> y = x.Select(i => i.ToString());

Or, if you prefer query syntax:

Task<int> x = // ... Task<string> y = from i in x select i.ToString();

In both cases, you start with a Task<int> which you map into a Task<string>. Perhaps you've noticed that these two examples closely resemble the equivalent Lazy functor examples. The resemblance isn't coincidental. The same abstraction is in use in both places. This is the functor abstraction. That's what this article series is all about, after all.

The difference between the Task functor and the Lazy functor is that lazy computations don't run until forced. Tasks, on the other hand, typically start running in the background when created. Thus, when you finally await the value, you may actually not have to wait for it. This does, however, depend on how you created the initial task.

First functor law for Task #

The Select method obeys the first functor law. As usual in this article series, actually proving that this is the case belongs to the realm of computer science. Instead of proving that the law holds, you can use property-based testing to demonstrate that it does. The following example shows a single property written with FsCheck 2.11.0 and xUnit.net 2.4.0.

[Property(QuietOnSuccess = true)] public void TaskObeysFirstFunctorLaw(int i) { var left = Task.FromResult(i); var right = Task.FromResult(i).Select(x => x); Assert.Equal(left.Result, right.Result); }

This property accesses the Result property of the Tasks involved. This is typically not the preferred way to pull the value of Tasks, but I decided to do it like this since FsCheck 2.4.0 doesn't support asynchronous properties.

Even though you may feel that a property-based test gives you more confidence than a few hard-coded examples, such a test is nothing but a demonstration of the first functor law. It's no proof, and it only demonstrates that the law holds for Task<int>, not that it holds for Task<string>, Task<Product>, etcetera.

Second functor law for Task #

As is the case with the first functor law, you can also use a property to demonstrate that the second functor law holds:

[Property(QuietOnSuccess = true)] public void TaskObeysSecondFunctorLaw( Func<string, byte> f, Func<int, string> g, int i) { var left = Task.FromResult(i).Select(g).Select(f); var right = Task.FromResult(i).Select(x => f(g(x))); Assert.Equal(left.Result, right.Result); }

Again the same admonitions apply: that property is no proof. It does show, however, that given two functions, f and g, it doesn't matter if you map a Task in one or two steps. The output is the same in both cases.

Async functor #

F# had asynchronous workflows long before C#, so it uses a slightly different model, supported by separate types. Instead of Task<T>, F# relies on a generic type called Async<'T>. It's still a functor, since you can trivially implement a map function for it:

module Async = // 'a -> Async<'a> let fromValue x = async { return x } // ('a -> 'b) -> Async<'a> -> Async<'b> let map f x = async { let! x' = x return f x' }

The map function uses the async computation expression to access the value being computed asynchronously. You can use a let! binding to await the value computed in x, and then use the function f to translate that value. The return keyword turns the result into a new Async value.

With the map function, you can write code like this:

let (x : Async<int>) = // ... let (y : Async<string>) = x |> Async.map string

Once you've composed an asynchronous workflow to your liking, you can run it to compute the value in which you're interested:

> Async.RunSynchronously y;; val it : string = "42"

This is the main difference between F# asynchronous workflows and .NET Tasks. You have to explicitly run an asynchronous workflows, whereas Tasks are usually, implicitly, already running in the background.

First functor law for Async #

The Async.map function obeys the first functor law. Like above, you can use FsCheck to demonstrate how that works:

[<Property(QuietOnSuccess = true)>] let ``Async obeys first functor law`` (i : int) = let left = Async.fromValue i let right = Async.fromValue i |> Async.map id Async.RunSynchronously left =! Async.RunSynchronously right

In addition to FsCheck and xUnit.net, this property also uses Unquote 4.0.0 for the assertion. The =! operator is an assertion that the left-hand side must equal the right-hand side. If it doesn't, then the operator throws a descriptive exception.

Second functor law for Async #

As is the case with the first functor law, you can also use a property to demonstrate that the second functor law holds:

[<Property(QuietOnSuccess = true)>] let ``Async obeys second functor law`` (f : string -> byte) g (i : int) = let left = Async.fromValue i |> Async.map g |> Async.map f let right = Async.fromValue i |> Async.map (g >> f) Async.RunSynchronously left =! Async.RunSynchronously right

As usual, the second functor law states that given two arbitrary (but pure) functions f and g, it doesn't matter if you map an asynchronous workflow in one or two steps. There could be a difference in performance, but the functor laws don't concern themselves with the time dimension.

Both of the above properties use the Async.fromValue helper function to create Async values. Perhaps you consider it cheating that it immediately produces a value, but you can add a delay if you want to pretend that actual asynchronous computation takes place. It'll make the tests run slower, but otherwise will not affect the outcome.

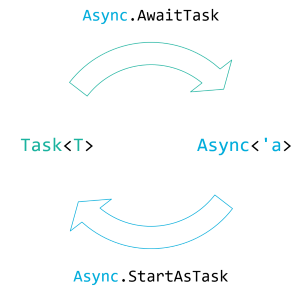

Task and Async isomorphism #

The reason I've covered both Task<T> and Async<'a> in the same article is that they're equivalent. You can translate a Task to an asynchronous workflow, or the other way around.

There's performance implications of going back and forth between Task<T> and Async<'a>, but there's no loss of information. You can, therefore, consider these to representations of asynchronous computations isomorphic.

Summary #

Whether you do asynchronous programming with Task<T> or Async<'a>, asynchronous computations form functors. This enables you to piecemeal compose asynchronous workflows.

Next: The Const functor.

Comments

I am with you. I also want to be pragmatic here and treat

Task<T>as a functor. It is definitely better than the alternative.At the same time, I want to know what prevents

Task<T>from actually being a functor so that I can compensate when needed.Can you elaborate about this? Why is

Task<T>not referentially transparent? Why is the situation worse with impure operations? What issue remains when restricting to pure functions? Is this related to how the stack trace is closely related to how many timesawaitappears in the code?Tyson, thank you for writing. That .NET tasks aren't referentially transparent is a result of memoisation, as Diogo Castro pointed out to me.

The coming article about Task asynchronous programming as an IO surrogate will also discuss this topic.

Ha! So funny. It is the same caching behavior that I pointed out in this comment. I wish I had known about Diogo's comment. I could have just linked there.

I am still not completely following though. Are you saying that this caching behavior prevents .NET Tasks from satisfying one of the functor laws? If so, is it the identity law or the composition law? If it is the composition law, what are the two functions that demonstate the failure? Even when allowing impure functions, I can't think of an example. However, I will keep thinking about this and comment again if I find an example.

Tyson, I am, in general trying to avoid claiming that any of this applies in the presence of impurity. Take something as trivial as

Select(i => new Random().Next(i)), for Task or any other 'functor'. It's not even going to evaluate to the same outcome between two runs.I think I understand your hesitation now regarding impurity. I also think I can argue that the existence of impure functions in C# does not prevent

Task<T>from being a functor.Before I give that argument and we consider if it works, I want to make sure there isn't a simpler issue only involving pure functions the prevents

Task<T>from being a functor.Your use of "mostly" makes me think that you believe there is a counterexample only involving pure functions that shows

Task<T>is not a functor. Do I correctly understanding what you meant by that sentence? If so, can you share that counterexample? If not, can you elaborate so that I can better understand what you meant.Tyson, I wrote this article two years ago. I can't recall if I had anything specific in mind, or if it was just a throwaway phrase. Even if I had a specific counter-example in mind, I might have been wrong, just like the consensus is about Fermat's last theorem.

If you can produce an example, however, you'd prove me right 😀