Functors by Mark Seemann

A functor is a common abstraction. While typically associated with functional programming, functors exist in C# as well.

This article series is part of a larger series of articles about functors, applicatives, and other mappable containers.

Programming is about abstraction, since you can't manipulate individual sub-atomic particles on your circuit boards. Some abstractions are well-known because they're rooted in mathematics. Particularly, category theory has proven to be fertile ground for functional programming. Some of the concepts from category theory apply to object-oriented programming as well; all you need is generics, which is a feature of both C# and Java.

In previous articles, you got an introduction to the specific Test Data Builder and Test Data Generator functors. Functors are more common than you may realise, although in programming, we usually work with a subset of functors called endofunctors. In daily speak, however, we just call them functors.

In the next series of articles, you'll see plenty of examples of functors, with code examples in both C#, F#, and Haskell. These articles are mostly aimed at object-oriented programmers curious about the concept.

- The Maybe functor

- An Either functor

- A Tree functor

- A rose tree functor

- A Visitor functor

- Reactive functor

- The Identity functor

- The Lazy functor

- Asynchronous functors

- The Const functor

- The State functor

- The Reader functor

- The IO functor

- Monomorphic functors

- Set is not a functor

IEnumerable<T>. Since the combination of IEnumerable<T> and query syntax is already well-described, I'm not going to cover it explicitly here.

If you understand how LINQ, IEnumerable<T>, and C# query syntax works, however, all other functors should feel intuitive. That's the power of abstractions.

Overview #

The purpose of this article isn't to give you a comprehensive introduction to the category theory of functors. Rather, the purpose is to give you an opportunity to learn how it translates to object-oriented code like C#. For a great introduction to functors, see Bartosz Milewski's explanation with illustrations.

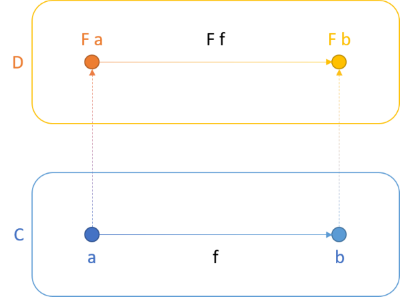

In short, a functor is a mapping between two categories. A functor maps not only objects, but also functions (called morphisms) between objects. For instance, a functor F may be a mapping between the categories C and D:

Not only does F map a from C to F a in D (and likewise for b), it also maps the function f to F f. Functors preserve the structure between objects. You'll often hear the phrase that a functor is a structure-preserving map. One example of this regards lists. You can translate a List<int> to a List<string>, but the translation preserves the structure. This means that the resulting object is also a list, and the order of values within the lists doesn't change.

In category theory, categories are often named C, D, and so on, but an example of a category could be IEnumerable<T>. If you have a function that translates integers to strings, the source object (that's what it's called, but it's not the same as an OOP object) could be IEnumerable<int>, and the destination object could be IEnumerable<string>. A functor, then, represents the ability to go from IEnumerable<int> to IEnumerable<string>, and since the Select method gives you that ability, IEnumerable<T>.Select is a functor. In this case, you sort of 'stay within' the category of IEnumerable<T>, only you change the generic type argument, so this functor is really an endofunctor (the endo prefix is from Greek, meaning within).

As a rule of thumb, if you have a type with a generic type argument, it's a candidate to be a functor. Such a type is not always a functor, because it also depends on where the generic type argument appears, and some other rules.

Fundamentally, you must be able to implement a method for your generic type that looks like this:

public Functor<TResult> Select<TResult>(Func<T, TResult> selector)

Here, I've defined the Select method as an instance method on a class called Functor<T>, but often, as is the case with IEnumerable<T>, the method is instead implemented as an extension method. You don't have to name it Select, but doing so enables query syntax in C#:

var dest = from x in source select x.ToString();

Here, source is a Functor<int> object.

If you don't name the method Select, it could still be a functor, but then query syntax wouldn't work. Instead, normal method-call syntax would be your only option. This is, however, a specific C# language feature. F#, for example, has no particular built-in awareness of functors, although most libraries name the central function map. In Haskell, Functor is a typeclass that defines a function called fmap.

The common trait is that there's an input value (Functor<T> in the above C# code snippet), which, when combined with a mapping function (Func<T, TResult>), returns an output value of the same generic type, but with a different generic type argument (Functor<TResult>).

Laws #

Defining a Select method isn't enough. The method must also obey the so-called functor laws. These are quite intuitive laws that govern that a functor behaves correctly.

The first law is that mapping the identity function returns the functor unchanged. The identity function is a function that returns all input unchanged. (It's called the identity function because it's the identity for the endomorphism monoid.) In F# and Haskell, this is simply a built-in function called id.

In C#, you can write a demonstration of the law as a unit test:

[Theory] [InlineData(-101)] [InlineData(-1)] [InlineData(0)] [InlineData(1)] [InlineData(42)] [InlineData(1337)] public void FunctorObeysFirstFunctorLaw(int value) { Func<int, int> id = x => x; var sut = new Functor<int>(value); Assert.Equal(sut, sut.Select(id)); }

While this doesn't prove that the first law holds for all values and all generic type arguments, it illustrates what's going on.

Since C# doesn't have a built-in identity function, the test creates a specialised identity function for integers, and calls it id. It simply returns all input values unchanged. Since id doesn't change the value, then Select(id) shouldn't change the functor, either. There's nothing more to the first law than this.

The second law states that if you have two functions, f and g, then mapping over one after the other should be the same as mapping over the composition of f and g. In C#, you can illustrate it like this:

[Theory] [InlineData(-101)] [InlineData(-1)] [InlineData(0)] [InlineData(1)] [InlineData(42)] [InlineData(1337)] public void FunctorObeysSecondFunctorLaw(int value) { Func<int, string> g = i => i.ToString(); Func<string, string> f = s => new string(s.Reverse().ToArray()); var sut = new Functor<int>(value); Assert.Equal(sut.Select(g).Select(f), sut.Select(i => f(g(i)))); }

Here, g is a function that translates an int to a string, and f reverses a string. Since g returns string, you can compose it with f, which takes string as input.

As the assertion points out, it shouldn't matter if you call Select piecemeal, first with g and then with f, or if you call Select with the composed function f(g(i)).

Summary #

This is not a monad tutorial; it's a functor tutorial. Functors are commonplace, so it's worth keeping an eye out for them. If you already understand how LINQ (or similar concepts in Java) work, then functors should be intuitive, because they are all based on the same underlying maths.

While this article is an overview article, it's also a part of a larger series of articles that explore what object-oriented programmers can learn from category theory.

Next: The Maybe functor.

Comments

My guess is that you were thinking of Haskell's

Functortypeclass when you wrote that. As Haskell documentation forFunctorsays,To explain the Haskell syntax for anyone unfamiliar,

fis a generic type with type parametera. So indeed, it is necessary to be a Haskell type to be generic to be an instance of theFunctortypeclass. However, the concept of a functor in programming is not limited to Haskell'sFunctortypeclass.For any type

Tincluding non-generic types, the category containing only a single object representingTcan have (nontrivial) endofunctors. For example, consider a record of typeRin F# with a field of both name and typeF. Thenlet mapF f r = { r with F = f r.F }is themapfunction the satisfies the functor laws for the fieldFfor recordR. This holds even whenFis not a type parameter ofR. I would say thatRis a functor inF.I have realized within just the past three weeks how valuable it is to have a

mapfunction for every field of every record that I define. For example, I was able to greatly simplify theSubModelSeqsample in Elmish.WPF in part because of suchmapfunctions. I am especially pleased with the mainupdatefunction, which heavily uses thesemapfunctions. It went from this to this.In particular, I was able to eta-reduce the

Modelargument. To be clear, the goal is not point-free style for its own sake. Instead, it is one of perspective. In the previous implementation, the body explicitly depended on both theMsgandModelarguments and explicitly returned aModelinstance. In the new implementation, the body only explicitly depends on theMsgargument and explicitly returns a function with typeModel -> Model. By only having to pattern match on theMsgargument (and not having to worry about how to exactly map from oneModelinstance to the next), the implementation is much simpler. Such is the expressive power of high-order functions.All this (and much more in my application at work) from realizing that a functor doesn't have to be generic.

I am looking into the possibility of generating these

mapfunctions using Myrid.Tyson, thank you for writing. I think that you're right.

To be honest, I still find the category theory underpinnings of functional programming concepts to be a little hazy. For instance, in category theory, a functor is a mapping between categories. When category theory is translated into Haskell, people usually discuss Haskell as constituting a single large category called Hask. In that light, everything that goes on in Haskell just maps from objects in Hask to objects in Hask. In that light, I still find it difficult to distinguish between morphisms and functors.

I'm going to need to think about this some more, but my intuition is that one can also find 'smaller' categories embedded in Hask, e.g. the category of Boolean values, or the category of strings, and so on.

What I'm trying to get across is that I haven't thought enough about the boundaries of a concept such as functor. It's clear that some containers with generic types form functors, but are generics required? You argue that they aren't required, and I think that you are right.

Generics are, however, required at the language level, as you've also pointed out. I think that this is also the case for F# and C#, but I admit that since the thought hadn't crossed my mind until now, I actually don't know. If you define a

Selectmethod that takes aFunc<T, T>instead of aFunc<T, TResult>, does query syntax still work?For what it's worth, there's a Haskell library that defines some type classes for monomorphic containers, including

This strongly suggests thatMonoFunctor. As it claims:MonoFunctorinstances are functors, too.I agree that despite the brevity of copy-and-update expressions, the particular use case that you describe can still seem verbose to sensitive souls. It doesn't look too bad with the example you give (

r.F), but usually, value and field names are longer, and then reading the field, applying a function, and setting the field again starts to feel inconvenient. I've been there.Once you start down the path of wanting to make it easier to 'reach into' a record structure to update parts of it, you quickly encounter lenses. As far as I can tell, your

mapfunction looks equivalent to a function that the lens library callsover.I agree that lenses can solve some real problems, and it seems that your use case was one of them.

FWIW, I recently answered a Stack Overflow question about the presence of general functors in programming. Perhaps you'll find it useful.

Also, I've now added an article about monomorphic functors.