Retiring old service versions by Mark Seemann

A few ideas on how to retire old versions of a web service.

I was recently listening to a .NET Rocks! episode on web APIs, and one of the topics that came up was how to retire old versions of a web service. It's not easy to do, but not necessarily impossible.

The best approach to API versioning is to never break compatibility. As long as there's no breaking changes, you don't have to version your API. It's rarely possible to completely avoid breaking changes, but the fewer of those that you introduce, the fewer API version you have to maintain. I've previously described how to version REST APIs, but this article doesn't assume any particular versioning strategy.

Sooner or later you'll have an old version that you'd like to retire. How do you do that?

Incentives #

First, take a minute to understand why some clients keep using old versions of your API. It may be obvious, but I meet enough programmers who never give incentives a thought that I find it worthwhile to point out.

When you introduce a breaking change, by definition this is a change that breaks clients. Thus, upgrading from an old version to a newer version of your API is likely to give client developers extra work. If what they have already works to their satisfaction, why should they upgrade their clients?

You might argue that your new version is 'better' because it has more features, or is faster, or whatever it is that makes it better. Still, if the old version is good enough for a particular purpose, some clients are going to stay there. The client maintainers have no incentives to upgrade. There's only cost, and no benefit, to upgrading.

Even if the developers who maintain those clients would like to upgrade, they may be prohibited from doing so by their managers. If there's no business reason to upgrade, efforts are better used somewhere else.

Advance warning #

Web services exist in various contexts. Some are only available on an internal network, while others are publicly available on the internet. Some require an authentication token or API key, while others allow anonymous client access.

With some services, you have a way to contact every single client developer. With other services, you don't know who uses your service.

Regardless of the situation, when you wish to retire a version, you should first try to give clients advance warning. If you have an address list of all client developers, you can simply write them all, but you can't expect that everyone reads their mail. If you don't know the clients, you can publish the warning. If you have a blog or a marketing site, you can publish the warning there. If you run a mailing list, you can write about the upcoming change there. You can tweet it, post it on Facebook, or dance it on TikTok.

Depending on SLAs and contracts, there may even be a legally valid communications channel that you can use.

Give advance warning. That's the decent thing to do.

Slow it down #

Even with advance warning, not everyone gets the message. Or, even if everyone got the message, some people deliberately decide to ignore it. Consider their incentives. They may gamble that as long as your logs show that they use the old version, you'll keep it online. What do you do then?

You can, of course, just take the version off line. That's going to break clients that still depend on that version. That's rarely the best course of action.

Another option is to degrade the performance of that version. Make it slower. You can simply add a constant delay when clients access that service, or you can gradually degrade performance.

Many HTTP client libraries have long timeouts. For example, the default HttpClient timeout is 100 seconds. Imagine that you want to introduce a gradual performance degradation that starts at no delay on June 1, 2020 and reaches 100 seconds after one year. You can use the formula d = 100 s * (t - t0) / 1 year, where d is the delay, t is the current time, and t0 is the start time (e.g. June 1, 2020). This'll cause requests for resources to gradually slow down. After a year, clients still talking to the retiring version will begin to time out.

You can think of this as another way to give advance warning. With the gradual deterioration of performance, users will likely notice the long wait times well before calls actually time out.

When client developers contact you about the bad performance, you can tell them that the issue is fixed in more recent versions. You've just given the client organisation an incentive to upgrade.

Failure injection #

Another option is to deliberately make the service err now and then. Randomly return a 500 Internal Server Error from time to time, even if the service can handle the request.

Like deliberate performance degradation, you can gradually make the deprecated version more and more unreliable. Again, end users are likely to start complaining about the unreliability of the system long before it becomes entirely useless.

Reverse proxy #

One of the many benefits of HTTP-based services is that you can put a reverse proxy in front of your application servers. I've no idea how to configure or operate NGINX or Varnish, but from talking to people who do know, I get the impression that they're quite scriptable.

Since the above ideas are independent of actual service implementation or behaviour, it's a generic problem that you should seek to address with general-purpose software.

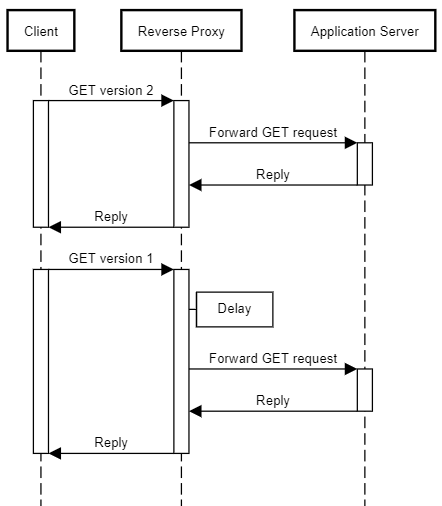

Imagine having a general-purpose reverse proxy that detects whether incoming HTTP requests are for the version you'd like to retire (version 1 in the diagram) or another version. If the proxy detects that the request is for a retiring version, it inserts a delay before it forward the request to the application server. For all requests for current versions, it just forwards the request.

I could imagine doing something similar with failure injections.

Legal ramifications #

All of the above are only ideas. If you can use them, great. Consider the implications, though. You may be legally obliged to keep an SLA. In that case, you can't degrade the performance or reliability below the SLA level.

In any case, I don't think you should do any of these things lightly. Involve relevant stakeholders before you engage in something like the above.

Legal specialists are as careful and conservative as traditional operations teams. Their default reaction to any change proposal is to say no. That's not a judgement on their character or morals, but simply another observation based on incentives. As long as everything works as it's supposed to work, any change represents a risk. Legal specialists, like operations teams, are typically embedded in incentive systems that punish risk-taking.

To counter other stakeholders' reluctance to engage in unorthodox behaviour, you'll have to explain why retiring an old version of the service is important. It works best if you can quantify the reason. If you can, measure how much extra time you waste on maintaining the old version. If the old version runs on separate hardware, or a separate cloud service, quantify the cost overhead.

If you can't produce a compelling argument to retire an old version, then perhaps it isn't that important after all.

Logs #

Server logs can be useful. They can tell you how many requests the old version serves, which IP addresses they come from, at which times or dates you have most traffic, and whether the usage trend is increasing or decreasing.

These measures can be used to support your argument that a particular version should be retired.

Conclusion #

Versioning web services is already a complex subject, but once you've figured it out, you'll sooner or later want to retire an old version of your API. If some clients still make good use of that version, you'll have to give them incentive to upgrade to a newer version.

It's best if you can proactively make clients migrate, so prioritise amiable solutions. Sometimes, however, you have no way to reach all client developers, or no obvious way to motivate them to upgrade. In those cases, gentle and gradual performance or reliability degradation of deprecated versions could be a way.

I present these ideas as nothing more than that: ideas. Use them if they make sense in your context, but think things through. The responsibility is yours.

Comments

Hi Mark. As always an excellent piece. A few comments if I may.

An assumption seems to be, that the client is able to update to a new version of the API, but is not inclined to do so for various reasons. I work with organisations where updating a client if nearly impossible. Not because of lack of will, but due to other factors such as government regulations, physical location of client, hardware version or capabilities of said client to name just a few.

We have a tendency in the software industry to see updates as a question of 'running Windows update' and then all is good. Most likely because that is the world we live in. If we wish to update a program or even an OS, it is fairly easy even your above considerations taken into account.

In the 'physical' world of manufacturing (or pharmacy or mining or ...) the situation is different. The lifetime of the 'thing' running the client is regularly measured in years or even decades and not weeks or months as it is for a piece of software.

Updates are often equal to bloating of resource requirements meaning you have to replace the hardware. This might not always be possible again for various reasons. Cost (company is pressed on margin or client is located in Outer Mongolia) or risk (client is located in Syria or some other hotspot) are some I've personally come across.

REST/HTTP is not used. I acknowledge that the original podcast from .NET Rocks! was about updating a web service. This does not change the premises of your arguments, but it potentially adds a layer of complication.

Karsten, thank you for writing. You are correct that the underlying assumption is that you can retire old versions.

I, too, have written REST APIs where retiring service versions weren't an option. These were APIs that consumer-grade hardware would communicate with. We had no way to assure that consumers would upgrade their hardware. Those boxes wouldn't have much of a user-interface. Owners might not realise that firmware updates were available, even if they were.

This article does, indeed, assume that the reader has made an informed decision that it's fundamentally acceptable to retire a service version. I should have made that more explicit.