In defence of multiple WiP by Mark Seemann

Programming isn't like factory work.

I was recently stuck on a programming problem. Specifically, part two of an Advent of Code puzzle, if you must know. As is my routine, I went for a run, which always helps to get unstuck. During the few hours away from the keyboard, I'd had a new idea. When I returned to the computer, I had my new algorithm implemented in about an hour, and it calculated the correct result in sub-second time.

I'm not writing this to brag. On the contrary, I suck at Advent of Code (which is a major reason that I do it). The point is rather that programming is fundamentally non-linear in effort. Not only are some algorithms orders of magnitudes faster than other algorithms, but it's also the case that the amount of time you put into solving a problem doesn't always correlate with the outcome.

Sometimes, the most productive way to solve a problem is to let it rest and go do something else.

One-piece flow #

Doesn't this conflict with the ideal of one-piece flow? That is, that you should only have one piece of work in progress (WiP).

Yes, it does.

It's not that I don't understand basic queue theory, haven't read The Goal, or that I'm unaware of the compelling explanations given by, among other people, Henrik Kniberg. I do, myself, lean (pun intended) towards lean software development.

I only offer the following as a counterpoint to other voices. As I've described before, when I seem to disagree with the mainstream view on certain topics, the explanation may rather be that I'm concerned with a different problem than other people are. If your problem is a dysfunctional organization where everyone have dozens of tasks in progress, nothing ever gets done because it's considered more important to start new work items than completing ongoing work, where 'utilization' is at 100% because of 'efficiency', then yes, I'd also recommend limiting WiP.

The idea in one-piece flow is that you're only working on one thing at a time.

Perhaps you can divide the task into subtasks, but you're only supposed to start something new when you're done with the current job. Compared to the alternative of starting a lot concurrent tasks in order to deal with wait times in the system, I agree with the argument that this is often better. One-piece flow often prompts you to take a good, hard look at where and how delays occur in your process.

Even so, I find it ironic that most of 'the Lean squad' is so busy blaming Taylorism for everything that's wrong with many software development organizations, only to go advocate for another management style rooted in factory work.

Programming isn't manufacturing.

Urgent or important #

As Eisenhower quoted an unnamed college president:

"I have two kinds of problems, the urgent and the important. The urgent are not important, and the important are never urgent."

It's hard to overstate how liberating it can be to ignore the urgent and focus on the important. Over decades, I keep returning to the realization that you often reach the best solutions to software problems by letting them stew.

I'm sure I've already told the following story elsewhere, but it bears repeating. Back in 2009 I started an open-source project called AutoFixture and also managed to convince my then-employer, Safewhere, to use it in our code base.

Maintaining or evolving AutoFixture wasn't my job, though. It was a work-related hobby, so nothing related to it was urgent. When in the office, I worked on Safewhere code, but biking back and forth between home and work, I thought about AutoFixture problems. Often, these problems would be informed by how we used it in Safewhere. My point is that the problems I was thinking about were real problems that I'd encountered in my day job, not just something I'd dreamt up for fun.

I was mostly thinking about API designs. Given that this was ideally a general-purpose open-source project, I didn't want to solve narrow problems with specific solutions. I wanted to find general designs that would address not only the immediate concerns, but also other problems that I had yet to discover.

Many an evening I spent trying out an idea I'd had on my bicycle. Often, it turned out that the idea wouldn't work. While that might be, in one sense, dismaying, on the other hand, it only meant that I'd learned about yet another way that didn't work.

Because there was no pressure to release a new version of AutoFixture, I could take the time to get it right. (After a fashion. You may disagree with the notion that AutoFixture is well-designed. I designed its APIs to the best of my abilities during the decade I lead the project. And when I discovered property-based testing, I passed on the reins.)

Get there earlier by starting later #

There's a 1944 science fiction short story by A. E. van Vogt called Far Centaurus that I'm now going to spoil.

In it, four astronauts embark on a 500-year journey to Alpha Centauri, using suspended animation. When they arrive, they discover that the system is long settled, from Earth.

During their 500 years en route, humans invented faster space travel. Even though later generations started later, they arrived earlier. They discovered a better way to get from a to b.

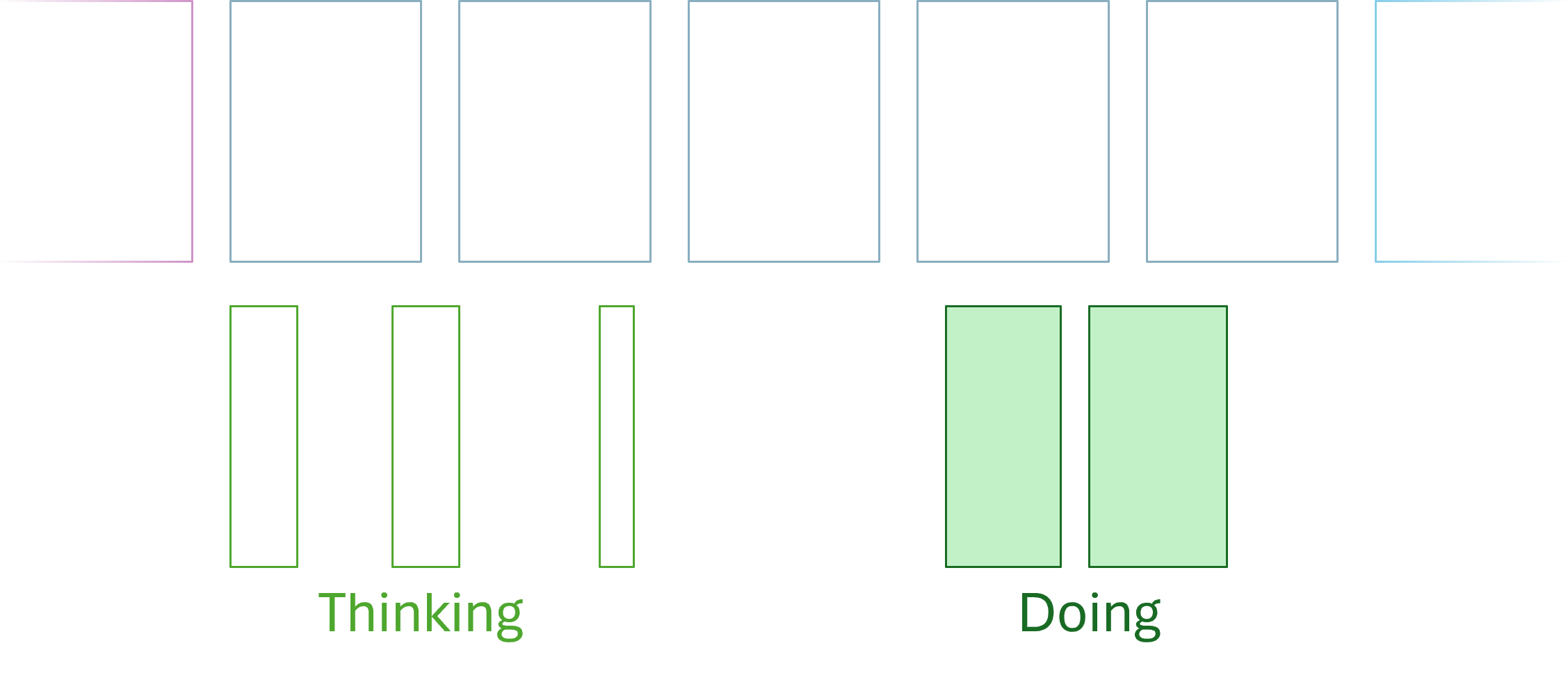

Compared to one-piece flow, we may illustrate this metaphor like this:

When presented with a problem, we don't start working on it right away. Or, we do, but the work we do is thinking rather than typing. We may even do some prototyping at that stage, but if no good solution presents itself, we put away the problem for a while.

We may return to the problem from time to time, and what may happen is that we realize that there's a much better, quicker way of accomplishing the goal than we first believed (as, again, recently happened to me). Once we have that realization, we may initiate the work, and it it may even turn out that we're done earlier than if we'd immediately started hacking at the problem.

By starting later, we've learned more. Like much knowledge work, software development is a profoundly non-linear endeavour. You may find a new way of doing things that are orders of magnitudes faster than what you originally had in mind. Not only in terms of big-O notation, but also in terms of implementation effort.

When doing Advent of Code, I've repeatedly been struck how the more efficient algorithm is often also simpler to implement.

Multiple WiP #

As the above figure suggests, you're probably not going to spend all your time thinking or doing. The figure has plenty of air in between the activities.

This may seem wasteful to efficiency nerds, but again: Knowledge work isn't factory work.

You can't think by command. If you've ever tried meditating, you'll know just how hard it is to empty your mind, or in any way control what goes on in your head. Focus on your breath. Indeed, and a few minutes later you snap out of a reverie about what to make for dinner, only to discover that you were able to focus on your breath for all of ten seconds.

As I already alluded to in the introduction, I regularly exercise during the work day. I also go grocery shopping, or do other chores. I've consistently found that I solve all hard problems when I'm away from the computer, not while I'm at it. I think Rich Hickey calls it hammock-driven development.

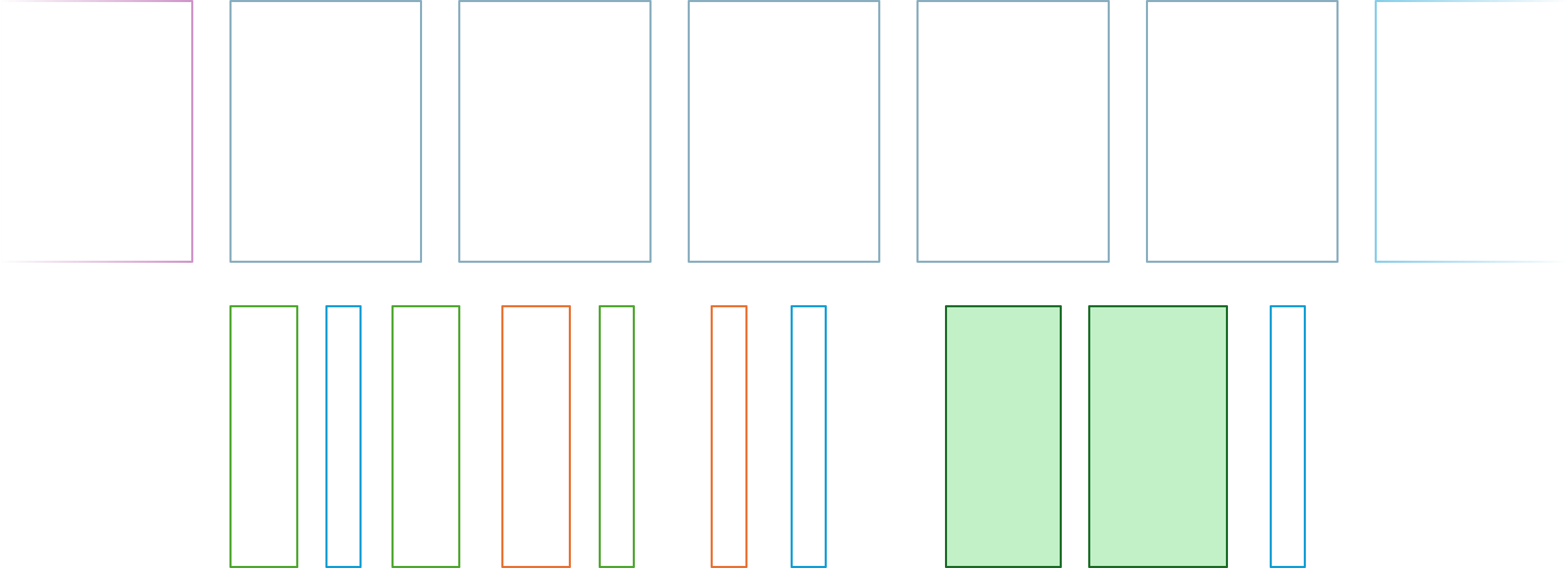

When presented with an interesting problem, I usually can't help thinking about it. What often happens, however, is that I'm mulling over multiple interesting problems during my day.

You could say that I actually have multiple pieces of work in progress. Some of them lie dormant for a long time, only to occasionally pop up and be put away again. Even so, I've had problems that I'd essentially given up on, only to resurface later when I'd learned a sufficient amount of new things. At that time, then, I sometimes realize that what I previously thought was impossible is actually quite simple.

It's amazing what you can accomplish when you focus on the things that are important, rather than the things that are urgent.

One size doesn't fit all #

How do I know that this will always work? How can I be sure that an orders-of-magnitude insight will occur if I just wait long enough?

There are no guarantees. My point is rather that this happens with surprising regularity. To me, at least.

Your software organization may include tasks that represent truly menial work. Yet, if you have too much of that, why haven't you automated it away?

Still, I'm not going to tell anyone how to run their development team. I'm only pointing out a weakness with the common one-piece narrative: It treats work as mostly a result of effort, and as if it were somehow interchangeable with other development tasks.

Most crucially, it models the amount of time required to complete a task as being independent of time: Whether you start a job today or in a month, it'll take x days to complete.

What if, instead, the effort was a function of time (as well as other factors)? The later you start, the simpler the work might be.

This of course doesn't happen automatically. Even if I have all my good ideas away from the keyboard, I still spend quite a bit of time at the keyboard. You need to work enough with a problem before inspiration can strike.

I'd recommend more slack time, more walks in the park, more grocery shopping, more doing the dishes.

Conclusion #

Programming is knowledge work. We may even consider it creative work. And while you can nurture creativity, you can't force it.

I find it useful to have multiple things going on at the same time, because concurrent tasks often cross-pollinate. What I learn from engaging with one task may produce a significant insight into another, otherwise unrelated problem. The lack of urgency, the lack of deadlines, foster this approach to problem-solving.

But I'm not going to tell you how to run your software development process. If you want to treat it as an assembly line, that's your decision.

You'll probably get work done anyway. Months of work can save days of thinking.