IO is special by Mark Seemann

Are IO expressions really referentially transparent programs?

Sometimes, when I discuss functional architecture or the IO container, a reader will argue that Haskell IO really is 'pure', 'referentially transparent', 'functional', or has another similar property.

The argument usually goes like this: An IO value is a composable description of an action, but not in itself an action. Since IO is a Monad instance, it composes via the usual monadic bind combinator >>=, or one of its derivatives.

Another point sometimes made is that you can 'call' an IO-valued action from within a pure function, as demonstrated by this toy example:

greet :: TimeOfDay -> String -> String greet timeOfDay name = let greeting = case () of _ | isMorning timeOfDay -> "Good morning" | isAfternoon timeOfDay -> "Good afternoon" | isEvening timeOfDay -> "Good evening" | otherwise -> "Hello" sideEffect = putStrLn "Side effect!" in if null name then greeting ++ "." else greeting ++ ", " ++ name ++ "."

This is effectively a Haskell port of the example given in Referential transparency of IO. Here, sideEffect is a value of the type IO (), even though greet is a pure function. Such examples are sometimes used to argue that the expression putStrLn "Side effect!" is pure, because it's deterministic and has no side effects.

Rather, sideEffect is a 'program' that describes an action. The program is a referentially transparent value, although actually running it is not.

As I also explained in Referential transparency of IO, the above function application is legal because greet never uses the value 'inside' the IO action. In fact, the compiler may choose to optimize the sideEffect expression away, and I believe that GHC does just that.

I've tried to summarize the most common arguments as succinctly as I can. While I could cite actual online discussions that I've had, I don't wish to single out anyone. I don't want to make this article appear as though it's an attack on anyone in particular. Rather, my position remains that IO is special, and I'll subsequently try to explain the reasoning.

Reductio ad absurdum #

While I could begin my argument stating the general case, backed up by citing some papers, I'm afraid I'll lose most readers in the process. Therefore I'll flip the argument around and start with a counter-example. What would happen if we accept the claim that IO is pure or referentially transparent?

It would follow that all Haskell code should be considered pure. That would include putStrLn "Hello, world." or launchMissiles. That I find that conclusion absurd may just be my subjective opinion, but it also seems to go against the original purpose of using IO to tackle the awkward squad.

Furthermore, and this may be more objective, it seems to allow writing everything in IO, and still call it 'functional'. What do I mean by that?

Functional imperative code #

If we accept that IO is pure, then we may decide to write everything in procedural style. We could, for example, implement rod-cutting by mirroring the imperative pseudocode used to describe the algorithm.

{-# LANGUAGE FlexibleContexts #-}

module RodCutting where

import Control.Monad (forM_, when)

import Data.Array.IO

import Data.IORef (newIORef, writeIORef, readIORef, modifyIORef)

cutRod :: (Ix i, Num i, Enum i, Num e, Bounded e, Ord e)

=> IOArray i e -> i -> IO (IOArray i e, IOArray i i)

cutRod p n = do

r <- newArray_ (0, n)

s <- newArray_ (1, n)

writeArray r 0 0 -- r[0] = 0

forM_ [1..n] $ \j -> do

q <- newIORef minBound -- q = -∞

forM_ [1..j] $ \i -> do

qValue <- readIORef q

p_i <- readArray p i

r_j_i <- readArray r (j - i)

when (qValue < p_i + r_j_i) $ do

writeIORef q (p_i + r_j_i) -- q = p[i] + r[j - i]

writeArray s j i -- s[j] = i

qValue' <- readIORef q

writeArray r j qValue' -- r[j] = q

return (r, s)

Ironically, the cutRod action remains referentially transparent, as is the original pseudocode from CLRS. This is because the algorithm itself is deterministic, and has no (external) side effects. Even so, the Haskell type system can't 'see' that. This implementation is intrinsically IO-valued.

Functional encapsulation #

You may think that this just proves the point that IO is pure, but it doesn't. We've always known that we can lift any pure value into IO using return: return 42 remains referentially transparent, even if it's contained in IO.

The reverse isn't always true. We can't conclude that code is referentially transparent when it's contained in IO. Usually, it isn't.

Be that as it may, why do we even care?

The problem is one of encapsulation. When an action like cutRod, above, returns an IO value, we're facing a dearth of guarantees. As users of the action, we may have many questions, most of which aren't answered by the type:

- Does

cutRodmodify the input arrayp? - Is

cutRoddeterministic? - Does

cutRodlaunch missiles? - Can I memoize the return values of

cutRod? - Does

cutRodsomehow keep a reference to the arrays that it returns? Can I be sure that a background thread, or a subsequent API call, doesn't mutate these arrays? In other words, is there a potential aliasing problem?

At best, such lack of guarantees lead to defensive coding, but usually it leads to bugs.

If, on the other hand, we were to write a version of cutRod that does not involve IO, we'd be able to answer all the above questions. The advantage would be that the function would be safer and easier to consume.

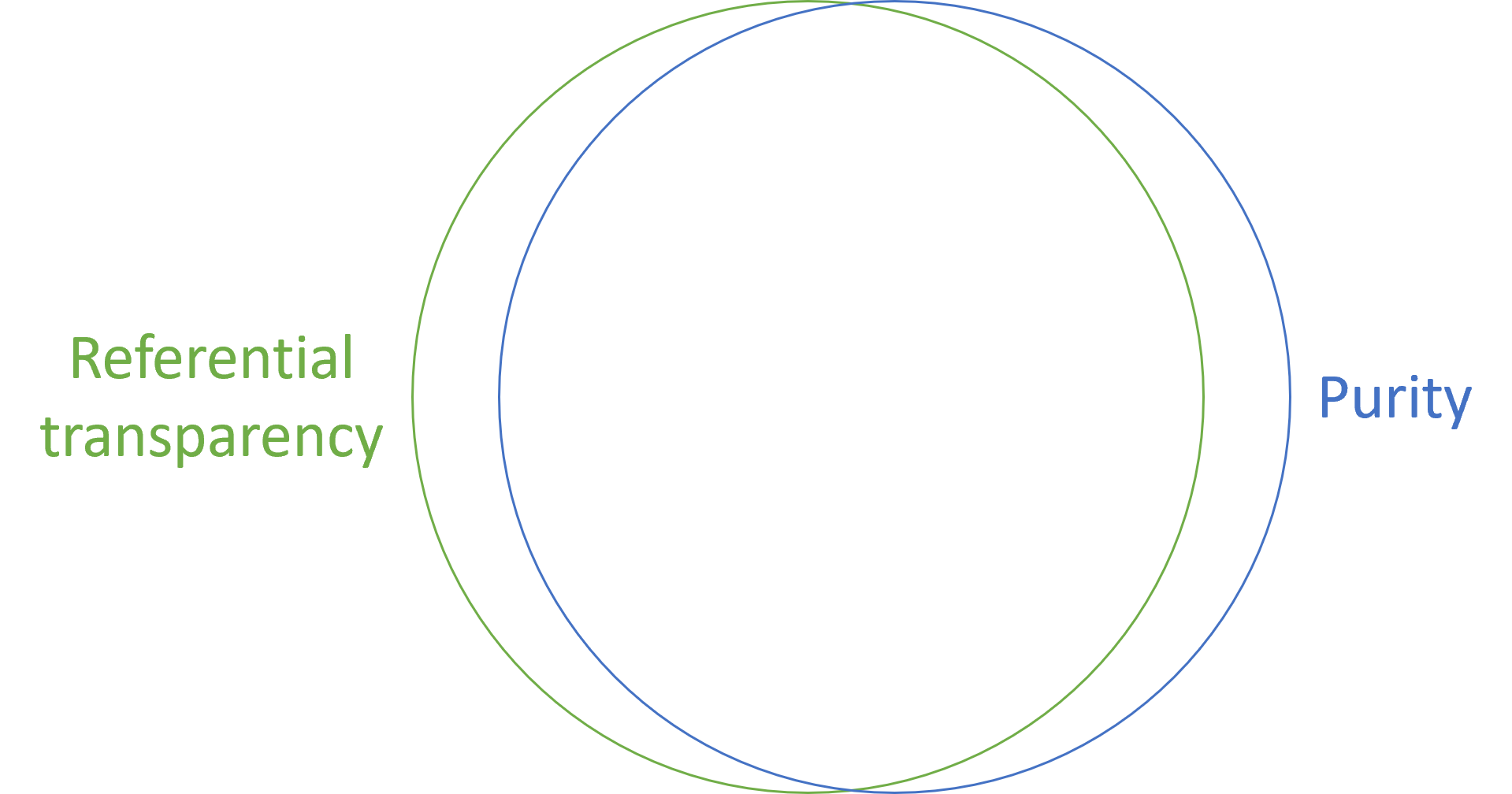

Referential transparency is not the same as purity #

This leads to a point that I failed to understand for years, until Tyson Williams pointed it out to me. Referential transparency is not the same as purity, although the overlap is substantial.

Of course, such a claim requires me to define the terms, but I'll try to keep it light. I'll define referential transparency as the property that allows replacing a function with the value it produces. Practically, it allows memoization. On the other hand, I'll define purity as functions that Haskell can distinguish from impure actions. In practice, this implies the absence of IO.

Usually this amounts to the same thing, but as we've seen above, it's possible to write referentially transparent code that nonetheless is embedded in IO. There are also examples of functions that look pure, although they may not be referentially transparent. Fortunately these are, in my experience, more rare.

That said, this is a digression. My agenda is to argue that IO is special. Yes, it's a Monad instance. Yes, it composes. No, it's not referentially transparent.

Semantics #

From the point of encapsulation, I've previously argued that referential transparency is attractive because it fits in your head. Code that is not referentially transparent usually doesn't.

Why is IO not referentially transparent? To repeat the argument that I sometimes run into, IO values describe programs. Every time your Haskell code runs, the same IO value describes the same program.

This strikes me as about as useful an assertion as insisting that all C code is referentially transparent. After all, a C program also describes the same program even if executed multiple times.

But you don't have to take my word for it. In Tackling the Awkward Squad: monadic input/output, concurrency, exceptions, and foreign-language calls in Haskell Simon Peyton Jones presents the semantics of Haskell.

"Our semantics is stratified in two levels: an inner denotational semantics that describes the behaviour of pure terms, while an outer monadic transition semantics describes the behaviour of

IOcomputations."

Over the next 20 pages, that paper goes into details on how IO is special. The point is that it has different semantics from the rest of Haskell.

Pure rod-cutting #

Before I close, I realize that the above cutRod action may cause distress with some readers. To relieve the tension I'll leave you with a pure implementation.

{-# LANGUAGE TupleSections #-}

module RodCutting (cutRod, solve) where

import Data.Foldable (foldl')

import Data.Map.Strict ((!))

import qualified Data.Map.Strict as Map

seekBetterCut :: (Ord a, Num a)

=> [a] -> Int -> (a, Map.Map Int a, Map.Map Int Int) -> Int

-> (a, Map.Map Int a, Map.Map Int Int)

seekBetterCut p j (q, r, s) i =

let price = p !! i

remainingRevenue = r ! (j - i)

(q', s') =

if q < price + remainingRevenue then

(price + remainingRevenue, Map.insert j i s)

else (q, s)

r' = Map.insert j q' r

in (q', r', s')

findBestCut :: (Bounded a, Ord a, Num a)

=> [a] -> (Map.Map Int a, Map.Map Int Int) -> Int

-> (Map.Map Int a, Map.Map Int Int)

findBestCut p (r, s) j =

let q = minBound -- q = -∞

(_, r', s') = foldl' (seekBetterCut p j) (q, r, s) [1..j]

in (r', s')

cutRod :: (Bounded a, Ord a, Num a)

=> [a] -> Int -> (Map.Map Int a, Map.Map Int Int)

cutRod p n = do

let r = Map.fromAscList $ map (, 0) [0..n] -- r[0:n] initialized to 0

let s = Map.fromAscList $ map (, 0) [1..n] -- s[1:n] initialized to 0

foldl' (findBestCut p) (r, s) [1..n]

solve :: (Bounded a, Ord a, Num a) => [a] -> Int -> [Int]

solve p n =

let (_, s) = cutRod p n

loop l n' =

if n' > 0 then

let cut = s ! n'

in loop (cut : l) (n' - cut)

else l

l' = loop [] n

in reverse l'

This is a fairly direct translation of the imperative algorithm. It's possible that you could come up with something more elegant. At least, I think that I did so in F#.

Regardless of the level of elegance of the implementation, this version of cutRod advertises its properties via its type. A client developer can now trivially answer the above questions, just by looking at the type: No, the function doesn't mutate the input list p. Yes, the function is deterministic. No, it doesn't launch missiles. Yes, you can memoize it. No, there's no aliasing problem.

Conclusion #

From time to time, I run into the claim that Haskell IO, being monadic and composable, is referentially transparent, and that it's only during execution that this property is lost.

I argue that such claims are of little practical interest. There are other parts of Haskell that remain referentially transparent, even during execution. Thus, IO is still special.

From a practical perspective, the reason I care about referential transparency is because the more you have of it, the simpler your code is; the better it fits in your head. The kind of referential transparency that some people argue that IO has does not have the property of making code simpler. In reality, IO code has the same inherent properties as code written in C, Python, Java, Fortran, etc.