Shift left on x by Mark Seemann

A difficult task may be easier if done sooner.

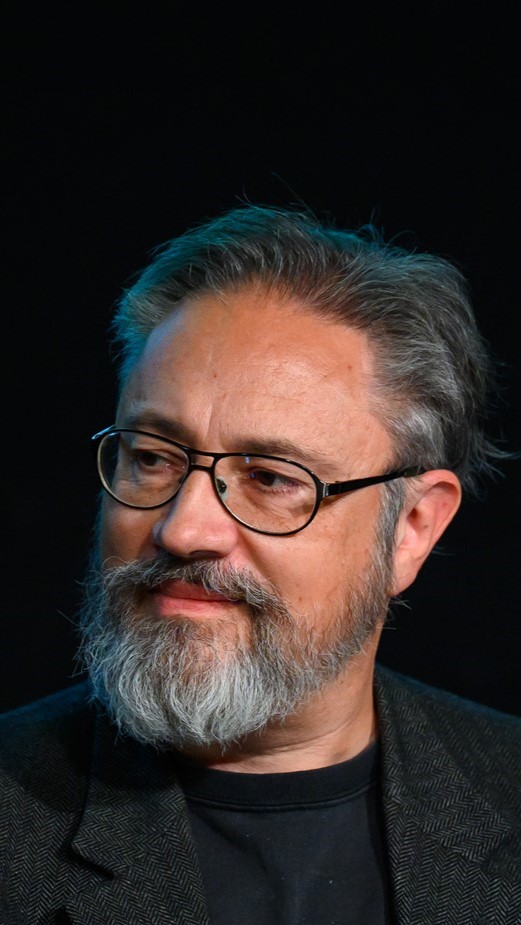

You've probably seen a figure like this before:

The point is that as time passes, the cost of doing something increases. This is often used to explain why test-driven development (TDD) or other agile methods are cost-effective alternatives to a waterfall process.

Last time I checked, however, there was scant scientific evidence for this curve.

Even so, it feels right. If you discover a bug while you write the code, it's much easier to fix it than if it's discovered weeks later.

Make security easier #

I was recently reminded of the above curve because a customer of mine was struggling with security; mostly authentication and authorization. They asked me if there was a software-engineering practice that could help them get a better handle on security. Since this is a customer who's otherwise quite knowledgeable about agile methods and software engineering, I was a little surprised that they hadn't heard the phrase shift left on security.

The idea fits with the above diagram. 'Shifting left' implies moving to the left on the time axis. In other words, do things sooner. Specifically related to security, the idea is to include security concerns early in every software development process.

There's little new in this. Writing Secure Code from 2004 describes how threat modelling is part of secure coding practices. This is something I've had in the back of my mind since reading the book. I also describe the technique and give an example in Code That Fits in Your Head.

If I know that a system I'm developing requires authentication, some of the first automated acceptance tests I write is one that successfully authenticates against the system, and one or more that fail to do so. Again, the code base that accompanies Code That Fits in Your Head has examples of this.

Since my customer's question reminded me of this practice, I began pondering the idea of 'shifting left'. Since it's both touted as a benefit of TDD and DevSecOps, an obvious pattern suggests itself.

Sufficient requirements #

It's been years since I last drew the above diagram. As I implied, one problem with it is that there seems to be little quantifiable evidence for that relationship. On the other hand, you've surely had the experience that some tasks become harder, the longer you wait. I'll list some example later.

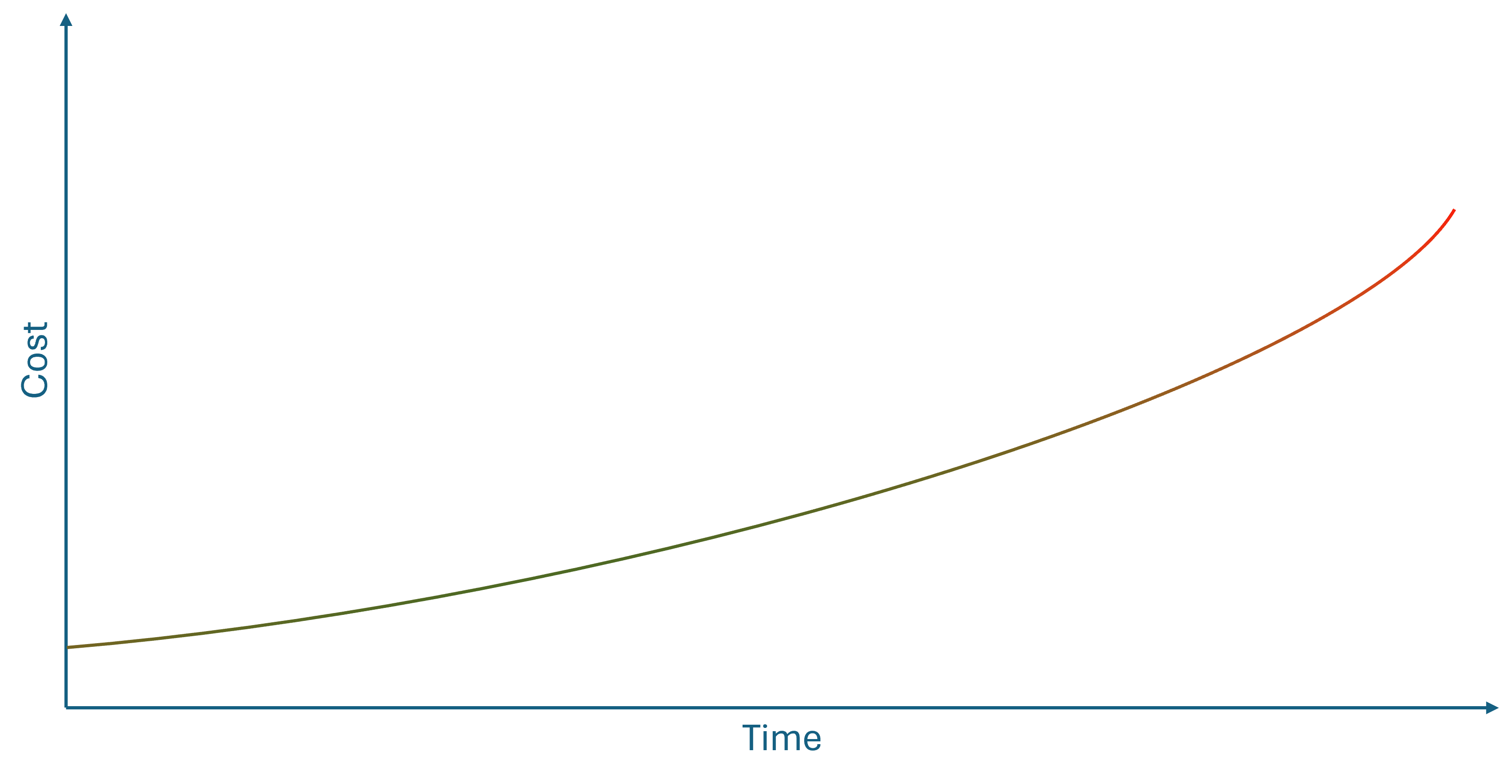

While we may not have solid scientific evidence that a cost curve looks like above, it doesn't have to look like that to make shifting left worthwhile. All it takes, really, is that the relationship is non-decreasing, and increases at least once. It doesn't have to be polynomial or exponential; it may be linear or logarithmic. It may even be a non-decreasing step function, like this:

This, as far as I can tell, is a sufficient condition to warrant shifting left on an activity. If you have even anecdotal evidence that it may be more costly to postpone an activity, do it sooner. In practice, I don't think that you need to wait for solid scientific evidence before you do this.

While not quite the same, it's a notion similar to the old agile saw: If it hurts, do it more often. Instead, we may phrase it as: If it gets harder with time, do it sooner.

Examples #

You've already seen two examples: TDD and security. Are there other examples where tackling problems sooner may decrease cost? Certainly.

A few, I cover in Code That Fits in Your Head. The earlier you automate the build process, the easier it is. The earlier you treat all warnings as errors, the easier it is. This seems almost self-explanatory, particularly when it comes to treating warnings as errors. In a brand-new code base, you have no warnings. In that situation, treating warnings as errors is free. When, later, a compiler warning appears, your code doesn't compile, and you're forced to immediately deal with it. At that time, it tends to be much easier to fix the issue, because no other code depends on the code with the warning.

A similar situation applies to an automated build. At the beginning, an automated build is a simple batch file with one command. dotnet test -c Release, stack test, py -m pytest, and so on. Later, when you need to deal with databases, security, third-party components, etc. you enhance the automated build 'just in time'.

Once you have an automated build, deployment is a small step further. In the beginning, deploying an application is typically as easy as copying some program files (compiled code or source files, depending on language) to the machines on which it's going to run. An exception may be if the deployment target is some sort of app store, with a vetting process that prevents you from deploying a walking skeleton. If, on the other hand, your organization controls the deployment target, the sooner you deploy a hello-world application, the easier it is.

Yet another shift-left example is using static code analysis or linting, particularly when combined with treating warnings as errors. Linters are usually free, and as I describe in Code That Fits in Your Head, I've always found it irrational that teams don't use them. Not that I don't understand the mechanism, because if you only turn them on at a time when the code base has already accumulated thousands of linter issues, the sheer volume is overwhelming.

Closely related to this discussion is the lean development notion that bugs are stop-the-line issues. The correct number of known bugs in the code base is zero. The correct number of unhandled exceptions in production is zero. This sounds unattainable to most people, but is possible if you shift left on managing defects.

In short:

- Shift left on security

- Shift left on testing

- Shift left on treating warnings as errors

- Shift left on automated builds

- Shift left on deployment

- Shift left on linting

- Shift left on defect management

This list is hardly exhaustive.

Shift right #

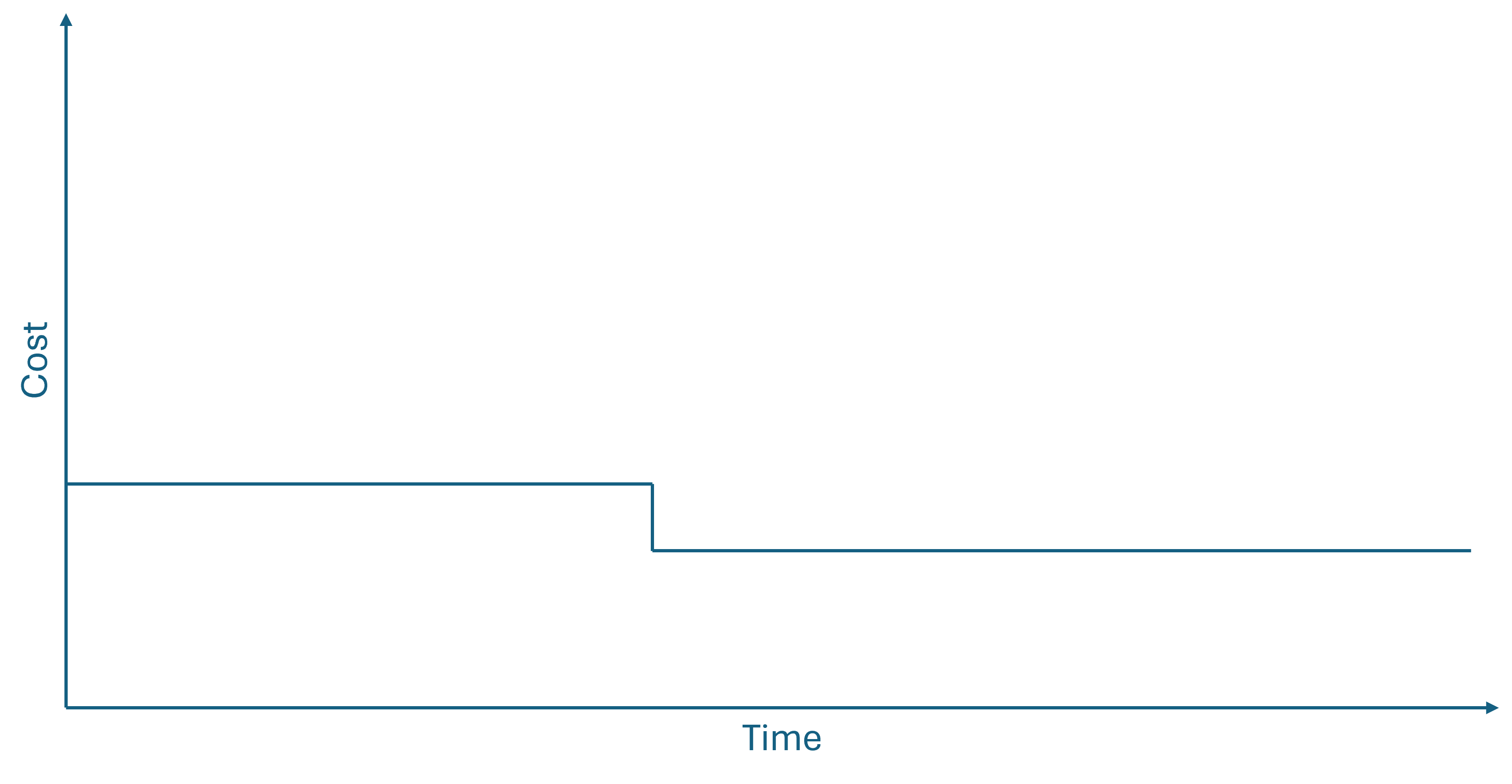

While it increases your productivity to do some things sooner, it's not a universal rule. Some things become easier, the longer you wait. In terms of time-to-cost curves, this happens whenever the curve is decreasing, even if only step-wise.

The danger of these figures is that they may give the impression of a deterministic process. That need not be the case, but if you have reason to believe that waiting until later may make solving a problem easier, consider waiting. The notion of waiting until the last responsible moment is central to lean or agile software development.

In a sense, you could view this is 'shifting right' on certain tasks. More than once I've experienced that if you wait long enough with a certain task, it becomes irrelevant. Not just easier to perform, but something that you don't need to do at all. What looked like a requirement early on turned out to be not at all what the customer or user wanted, after all.

When to do what #

How do you distinguish? How do you decide if shifting left or shifting right is more appropriate? In practice, it's rarely difficult. The shift-left list above contains the usual suspects. While the list may not be exhaustive, it's a well-known list of practices that countless teams have found easier to do sooner rather than later.

My own inclination would be to treat most other things as tasks that are better postponed. After all, you can't do everything as the first thing. Naturally, there has to be some sequencing of tasks.

Thinking about such decisions in terms of time-cost curves feels natural to me. I find it an easy framework to consider whether I should shift left or right on some activity.

Conclusion #

Some things are easier if you get started as soon as possible. Candidates include testing, deployment, security, and defect management. This is the case when there's a increasing relationship between time and cost. This relationship need not be a quantified function. Often, you can get by with a sense that 'if I do this now, it's going to be easy; if I wait, it's going to be harder.'

Conversely, some things are better postponed to the last responsible moment. This happens if the relation between time and cost is decreasing.

Perhaps we can simplify this analysis even further. Perhaps you don't even need to think of (step) functions. All you may need is to consider the partial order of tasks in terms of cost. Since I'm a visual thinker, however, increasing and decreasing functions come more naturally to me.