Refactoring registration flow to functional architecture by Mark Seemann

An example showing a refactoring from F# partial application 'dependency injection' to an impure/pure/impure sandwich.

In a comment to Dependency rejection, I wrote:

"I'd welcome a simplified, but still concrete example where the impure/pure/impure sandwich described here isn't going to be possible."Christer van der Meeren kindly replied with a suggestion.

The code in question relates to validationverification of user accounts. You can read the complete description in the linked comment, but I'll try to summarise it here. I'll then show a refactoring to a functional architecture - specifically, to an impure/pure/impure sandwich.

The code is available on GitHub.

Registration flow #

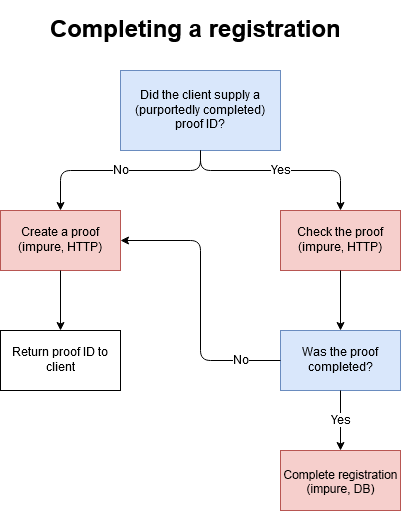

The system in question uses two-factor authentication with mobile phones. When you sign up for the service, you give your phone number. You then receive an SMS, and must use whatever is in that SMS to prove ownership of the phone number. Christer van der Meeren illustrates the flow like this:

He also supplies sample code:

let completeRegistrationWorkflow (createProof: Mobile -> Async<ProofId>) (verifyProof: Mobile -> ProofId -> Async<bool>) (completeRegistration: Registration -> Async<unit>) (proofId: ProofId option) (registration: Registration) : Async<CompleteRegistrationResult> = async { match proofId with | None -> let! proofId = createProof registration.Mobile return ProofRequired proofId | Some proofId -> let! isValid = verifyProof registration.Mobile proofId if isValid then do! completeRegistration registration return RegistrationCompleted else let! proofId = createProof registration.Mobile return ProofRequired proofId }

While this is F#, it's not functional, since it uses partial application for dependency injection. From the description, I find it safe to assume that we can consider Async as a surrogate for IO.

The code implies the existence of other types. I decided to define them like this:

type Mobile = Mobile of int type ProofId = ProofId of Guid type Registration = { Mobile : Mobile } type CompleteRegistrationResult = ProofRequired of ProofId | RegistrationCompleted

In reality, they're probably more complicated, but this is enough to make the code compile.

Is it possible to refactor completeRegistrationWorkflow to an impure/pure/impure sandwich?

Applicability #

It is possible to refactor completeRegistrationWorkflow to an impure/pure/impure sandwich. You'll see how to do that soon. Before we start that work, however, I'd like to warn against jumping to conclusions. It's possible that the problem statement doesn't capture some subtleties that one would have to deal with in the real world. It's also possible that I've misunderstood the essence of Christer van der Meeren's problem description.

It's (relatively) easy to teach the basics of programming. You teach a beginner about keywords, programming constructs, how to compile or interpret a program, and so on.

On the other hand, it's hard to write about dealing with complicated code. There are ways to make legacy code better, but the moves you have to make depend on myriad details. Complicated code is, by definition, something that's hard to learn. This means that truly complicated legacy code is rarely suitable for instructive examples. One has to strike a delicate balance and produce an example that looks complicated enough to warrant improvement, but on the other hand still be simple enough to be understood.

I think that Christer van der Meeren has struck that balance. With three dependencies, the sample code looks just complicated enough to warrant refactoring. On the other hand, you can understand what it's supposed to do in a few minutes. There's a risk, however, that the example is too simplified. That could weaken the result of the refactoring that follows. Could you still apply that refactoring if the problem was more complicated?

It's my experience that it's conspicuously often possible to implement an impure/pure/impure sandwich.

Fakes #

In the rest of this article, I want to show how to refactor completeRegistrationWorkflow to an impure/pure/impure sandwich. As Refactoring admonishes:

Right now, however, there's no tests, so I'm going to add some."to refactor, the essential precondition is [...] solid tests"

The tests will need some Test Doubles to stand in for the three dependency functions. If possible, I prefer state-based testing over interaction-based testing. First, then, we need some Fakes.

While completeRegistrationWorkflow takes three dependency functions, it looks as though there's only two architectural dependencies:

- A two-factor authentication service

- A registration database (or service)

type Fake2FA () = let mutable proofs = Map.empty member _.CreateProof mobile = match Map.tryFind mobile proofs with | Some (proofId, _) -> proofId | None -> let proofId = ProofId (Guid.NewGuid ()) proofs <- Map.add mobile (proofId, false) proofs proofId |> fun proofId -> async { return proofId } member _.VerifyProof mobile proofId = match Map.tryFind mobile proofs with | Some (_, true) -> true | _ -> false |> fun b -> async { return b } member _.VerifyMobile mobile = match Map.tryFind mobile proofs with | Some (proofId, _) -> proofs <- Map.add mobile (proofId, true) proofs | _ -> ()

In F#, I find that the easiest way to model a mutable resource is to use an object. This one just keeps track of a collection of proofs. The CreateProof method fits the function signature of completeRegistrationWorkflow's createProof function argument. It looks for an existing proof for the mobile number so that it can reuse the same proof multiple times. If there's no proof for mobile, it creates a new Guid and returns it after having first added it to the collection.

Likewise, the VerifyProof method fits the type of the verifyProof function argument. Proofs are actually tuples of IDs and a flag that keeps track of whether or not they've been verified. The method returns the flag if it's there, and false otherwise.

The third VerifyMobile method is a test-specific functionality that enables a test to mark a proof as having been verified via two-factor authentication.

Compared to Fake2FA, the Fake registration database is simple:

type FakeRegistrationDB () = inherit Collection<Registration> () member this.CompleteRegistration r = async { this.Add r }

Again, the CompleteRegistration method fits the completeRegistration function argument to completeRegistrationWorkflow. It just makes the inherited Add method Async.

Fixture creation #

My plan is to add Characterisation Tests so that I can refactor. I do, however, plan to change the API of the System Under Test (SUT). This could break the tests, which would defy their purpose. To protect against this, I'll test against a Facade. Initially, this Facade will be equivalent to the completeRegistrationWorkflow function, but this will change as I refactor.

In addition to the SUT Facade, the tests will also need access to the 'injected' dependencies. You can address this by creating a Fixture Object:

let createFixture () = let twoFA = Fake2FA () let db = FakeRegistrationDB () let sut = completeRegistrationWorkflow twoFA.CreateProof twoFA.VerifyProof db.CompleteRegistration sut, twoFA, db

This function return a triple of values: the SUT Facade and the two Fakes.

The SUT Facade is a partially applied function of the type ProofId option -> Registration -> Async<CompleteRegistrationResult>. In other words, it abstracts away the specifics about how impure actions are executed. It seems reasonable to imagine that the two remaining input arguments, ProofId option and Registration, are run-time values. Regardless of refactoring, the resulting function should be able to receive those arguments and produce the desired outcome.

Characterising the missing proof ID case #

It looks like the cyclomatic complexity of completeRegistrationWorkflow is 3, so you're going to need three Characterisation Tests. You can add them in any order you like, but in this case I found it natural to follow the order in which the branches are laid out in the SUT.

This test case verifies what happens if the proof ID is missing:

[<Theory>] [<InlineData 123>] [<InlineData 432>] let ``Missing proof ID`` mobile = async { let sut, twoFA, db = createFixture () let r = { Mobile = Mobile mobile } let! actual = sut None r let! expectedProofId = twoFA.CreateProof r.Mobile let expected = ProofRequired expectedProofId expected =! actual test <@ Seq.isEmpty db @> }

All the tests in this article use xUnit.net 2.4.0 with Unquote 5.0.0.

This test calls the sut Facade with a None proof ID and an arbitrary Registration r. Had I used a property-based testing framework such as FsCheck or Hedgehog, I could have made the Registration value itself an arbitrary test argument, but I thought that this was overkill for this situation.

In order to figure out the expectedProofId, the test relies on the behaviour of the Fake2FA class. The CreateProof method is idempotent, so calling it several times with the same number should return the same proof. In this test case, we expect the sut to have done so already, so calling the method once more from the test should return the same value that the SUT received. The test then wraps the proof ID in the ProofRequired case and uses Unquote's =! (must equal) operator to verify that expected is equal to actual.

Finally, the test also verifies that the reservations database remains empty.

Since this is a Characterisation Test it already passes, which makes it untrustworthy. How do I know that I didn't write a Tautological Assertion?

When I write Characterisation Tests, I always try to change the SUT to verify that the test fails for the appropriate reason. In order to fail the first assertion, I can make this change to the None branch of the SUT:

match proofId with | None -> //let! proofId = createProof registration.Mobile let proofId = ProofId (Guid.NewGuid ()) return ProofRequired proofId

This fails the expected =! actual assertion, as expected.

Likewise, you can fail the second assertion with this change:

match proofId with | None -> do! completeRegistration registration let! proofId = createProof registration.Mobile return ProofRequired proofId

The addition of the completeRegistration statement causes the test <@ Seq.isEmpty db @> assertion to fail, again as expected.

Now I trust that test.

Characterising the valid proof ID case #

Next, you have the case where all is good. The proof ID is present and valid. You can characterise the behaviour with this test:

[<Theory>] [<InlineData 987>] [<InlineData 247>] let ``Valid proof ID`` mobile = async { let sut, twoFA, db = createFixture () let r = { Mobile = Mobile mobile } let! p = twoFA.CreateProof r.Mobile twoFA.VerifyMobile r.Mobile let! actual = sut (Some p) r RegistrationCompleted =! actual test <@ Seq.contains r db @> }

This test uses CreateProof to create a proof before the sut is exercised. It also uses the test-specific VerifyMobile method to mark the mobile number (and thereby the proof) as valid.

Again, there's two assertions: one against the return value actual, and one that verifies that the registration database db now contains the registration r.

As before, you can't trust a Characterisation Test before you've seen it fail, so first edit the isValid branch of the SUT like this:

if isValid then do! completeRegistration registration //return RegistrationCompleted return ProofRequired proofId

This fails the RegistrationCompleted =! actual assertion, as expected.

Now make this change:

if isValid then //do! completeRegistration registration return RegistrationCompleted

Now the test <@ Seq.contains r db @> assertion fails, as expected.

This test also seems trustworthy.

Characterising the invalid proof ID case #

The final test case is when a proof ID exists, but it's invalid:

[<Theory>] [<InlineData 327>] [<InlineData 666>] let ``Invalid proof ID`` mobile = async { let sut, twoFA, db = createFixture () let r = { Mobile = Mobile mobile } let! p = twoFA.CreateProof r.Mobile let! actual = sut (Some p) r let! expectedProofId = twoFA.CreateProof r.Mobile let expected = ProofRequired expectedProofId expected =! actual test <@ Seq.isEmpty db @> }

The arrange phase of the test is comparable to the previous test case. The only difference is that the new test doesn't invoke twoFA.VerifyMobile r.Mobile. This leaves the generated proof ID p invalid.

The assertions, on the other hand, are identical to those of the Missing proof ID test case, which means that you can make the same edits to the else branch as you can to the None branch, as described above. If you do that, the assertions fail as they're supposed to. You can also trust this Characterisation Test.

Eta expansion #

While I want to keep the SUT Facade's type unchanged, I do want change the way I compose it. The goal is an impure/pure/impure sandwich: Do something impure first, then call a pure function with the data obtained, and finally do something impure with the output of the pure function.

This means that the composition is going to manipulate the input values to the SUT Facade. To make that easier, I perform an eta conversion on the sut:

let createFixture () = let twoFA = Fake2FA () let db = FakeRegistrationDB () let sut pid r = completeRegistrationWorkflow twoFA.CreateProof twoFA.VerifyProof db.CompleteRegistration pid r sut, twoFA, db

This doesn't change the behaviour or how the SUT is composed. It only makes the pid and r arguments explicitly visible.

Move proof verification #

When you consider the current implementation of completeRegistrationWorkflow, it seems that the impure actions are interleaved with the decision-making code. How to separate them?

The first opportunity that I identified was that it always calls verifyProof in the Some case. Whenever you want to call a method only in the Some case, but not in the None case, it suggest Option.map.

It should be possible to run Option.map (twoFA.VerifyProof r.Mobile) pid as the initial impure action of the impure/pure/impure sandwich. If that's possible, we could pass the output of that pure function as an argument to completeRegistrationWorkflow. That would already make it simpler:

let completeRegistrationWorkflow (createProof: Mobile -> Async<ProofId>) (completeRegistration: Registration -> Async<unit>) (proof: bool option) (registration: Registration) : Async<CompleteRegistrationResult> = async { match proof with | None -> let! proofId = createProof registration.Mobile return ProofRequired proofId | Some isValid -> if isValid then do! completeRegistration registration return RegistrationCompleted else let! proofId = createProof registration.Mobile return ProofRequired proofId }

Notice that by changing the proof argument to a bool option, you no longer need to call verifyProof, so you can remove it.

There's just one problem. The result of Option.map (twoFA.VerifyProof r.Mobile) pid is an Option<Async<bool>>, but you need an Option<bool>.

You can compose the SUT Facade in an asynchronous workflow, and use a let! binding, but that's not going to solve the problem. A let! binding only works when the outer container is Async. Here, the outermost container is Option. You're going to need to flip the containers around so that you get an Async<Option<bool>> that you can let!-bind:

let sut pid r = async { let! p = match Option.map (twoFA.VerifyProof r.Mobile) pid with | Some b -> async { let! b' = b return Some b' } | None -> async { return None } return! completeRegistrationWorkflow twoFA.CreateProof db.CompleteRegistration p r }

By pattern-matching on Option.map (twoFA.VerifyProof r.Mobile) pid, you can return one of two alternative asynchronous workflows.

Due to the let! binding, p is a bool option that you can pass to completeRegistrationWorkflow.

Traversal #

I know what you're going to say. You'll protest that I just moved complex behaviour out of completeRegistrationWorkflow. The implied assumption here is that completeRegistrationWorkflow is the top-level behaviour that you'd compose in a Composition Root. The createFixture function plays that role in this refactoring exercise.

You'd normally view the Composition Root as a Humble Object - an object that we accept isn't covered by tests because it has a cyclomatic complexity of one. This is no longer the case.

The conversion of Option<Async<bool>> to Async<Option<bool>> is, however, a well-known operation. In Haskell this is known as a traversal, and it's a completely generic operation:

// ('a -> Async<'b>) -> 'a option -> Async<'b option> let traverse f = function | Some x -> async { let! x' = f x return Some x' } | None -> async { return None }

You can put this function in a general-purpose module called AsyncOption and cover it by unit tests if you will. You can even put this module in a separate library; it's perfectly decoupled from the the specifics of the registration flow domain.

If you do that, completeRegistrationWorkflow doesn't change, but the composition does:

let sut pid r = async { let! p = AsyncOption.traverse (twoFA.VerifyProof r.Mobile) pid return! completeRegistrationWorkflow twoFA.CreateProof db.CompleteRegistration p r }

You're now back where you'd like to be: One impure action produces a value that you can pass to another function. There's no explicit branching in the code. The cyclomatic complexity remains one.

Change return type #

That first refactoring takes care of one out of three impure dependencies. Next, you can get rid of createProof. This one seems to be more difficult to get rid of. It doesn't seem to be required only in the Some case, so a map or traverse can't work. In both cases, however, the result of calling createProof is handled in exactly the same way.

Here's another common trick in functional programming: Decouple decisions from effects. Return a value that indicates the decision that the function reaches, and then let the second impure action of the impure/pure/impure sandwich act on the decision.

In this case, you can model your decision as a Mobile option. You might want to consider a more explicit type, in order to better communicate intent, but it's best to keep each refactoring step small:

let completeRegistrationWorkflow (completeRegistration: Registration -> Async<unit>) (proof: bool option) (registration: Registration) : Async<Mobile option> = async { match proof with | None -> return Some registration.Mobile | Some isValid -> if isValid then do! completeRegistration registration return None else return Some registration.Mobile }

Notice that the createProof dependency is no longer required. I've removed it from the argument list of completeRegistrationWorkflow.

The composition now looks like this:

let createFixture () = let twoFA = Fake2FA () let db = FakeRegistrationDB () let sut pid r = async { let! p = AsyncOption.traverse (twoFA.VerifyProof r.Mobile) pid let! res = completeRegistrationWorkflow db.CompleteRegistration p r let! pidr = AsyncOption.traverse twoFA.CreateProof res return pidr |> Option.map ProofRequired |> Option.defaultValue RegistrationCompleted }

Thanks to the let! binding, the result res is a Mobile option. You can now let the twoFA.CreateProof method traverse over res. This produces an Async<Option<ProofId>> that you can let!-bind to pidr - a ProofId option.

You can use Option.map to wrap the ProofId value in a ProofRequired case, if it's there. This step of the final pipeline produces a CompleteRegistrationResult option.

Finally, you can use Option.defaultValue to fold the option into a CompleteRegistrationResult. The default value is RegistrationCompleted. This is the case value that'll be used if the option is None.

Again, the composition has a cyclomatic complexity of one, and the type of the sut remains ProofId option -> Registration -> Async<CompleteRegistrationResult>. This is a true refactoring. The type of the SUT remains the same, and no behaviour changes. The tests still pass, even though I haven't had to edit them.

Change return type to Result #

Consider the intent of completeRegistrationWorkflow. The purpose of the operation is to complete a registration workflow. The name is quite explicit. Thus, the happy path is when the proof ID is valid and the function can call completeRegistration.

Usually, when you call a function that returns an option, the implied contract is that the Some case represents the happy path. That's not the case here. The Some case carries information about the error paths. This isn't idiomatic.

It'd be more appropriate to use a Result return value:

let completeRegistrationWorkflow (completeRegistration: Registration -> Async<unit>) (proof: bool option) (registration: Registration) : Async<Result<unit, Mobile>> = async { match proof with | None -> return Error registration.Mobile | Some isValid -> if isValid then do! completeRegistration registration return Ok () else return Error registration.Mobile }

This change is in itself small, but it does require some changes to the composition. Just as you had to add an Option.traverse function when the return type was an option, you'll now have to add similar functionality to Result. Result is also known as Either. Not only is it a bifunctor, you can also traverse both axes. Haskell calls this a bitraversable functor.

// ('a -> Async<'b>) -> ('c -> Async<'d>) -> Result<'a,'c> -> Async<Result<'b,'d>> let traverseBoth f g = function | Ok x -> async { let! x' = f x return Ok x' } | Error e -> async { let! e' = g e return Error e' }

Here I just decided to call the function traverseBoth and the module AsyncResult.

You're also going to need the equivalent of Option.defaultValue for Result. Something that translates both dimensions of Result into the same type. That's the Either catamorphism, so you could, for example, introduce another general-purpose function called cata:

// ('a -> 'b) -> ('c -> 'b) -> Result<'a,'c> -> 'b let cata f g = function | Ok x -> f x | Error e -> g e

This is another entirely general-purpose function that you can put in a general-purpose module called Result, in a general-purpose library. You can also cover it by unit tests, if you like.

These two general-purpose functions enable you to compose the workflow:

let createFixture () = let twoFA = Fake2FA () let db = FakeRegistrationDB () let sut pid r = async { let! p = AsyncOption.traverse (twoFA.VerifyProof r.Mobile) pid let! res = completeRegistrationWorkflow db.CompleteRegistration p r let! pidr = AsyncResult.traverseBoth (fun () -> async { return () }) twoFA.CreateProof res return pidr |> Result.cata (fun () -> RegistrationCompleted) ProofRequired } sut, twoFA, db

This looks more confused than previous iterations. From here, though, it'll get better again. The first two lines of code are the same as before, but now res is a Result<unit, Mobile>. You still need to let twoFA.CreateProof traverse the 'error path', but now you also need to take care of the happy path.

In the Ok case you have a unit value (()), but traverseBoth expects its f and g functions to return Async values. I could have fixed that with a more specialised traverseError function, but we'll soon move on from here, so it's hardly worthwhile.

In Haskell, you can 'elevate' a value simply with the pure function, but in F#, you need the more cumbersome (fun () -> async { return () }) to achieve the same effect.

The traversal produces pidr (for Proof ID Result) - a Result<unit, ProofId> value.

Finally, it uses Result.cata to turn both the Ok and Error dimensions into a single CompleteRegistrationResult that can be returned.

Removing the last dependency #

There's still one dependency left: the completeRegistration function, but it's now trivial to remove. Instead of calling the dependency function from within completeRegistrationWorkflow you can use the same trick as before. Decouple the decision from the effect.

Return information about the decision the function made. In the above incarnation of the code, the Ok dimension is currently empty, since it only returns unit. You can use that 'channel' to communicate that you decided to complete a registration:

let completeRegistrationWorkflow (proof: bool option) (registration: Registration) : Async<Result<Registration, Mobile>> = async { match proof with | None -> return Error registration.Mobile | Some isValid -> if isValid then return Ok registration else return Error registration.Mobile }

This is another small change. When isValid is true, the function no longer calls completeRegistration. Instead, it returns Ok registration. This means that the return type is now Async<Result<Registration, Mobile>>. It also means that you can remove the completeRegistration function argument.

In order to compose this variation, you need one new general-purpose function. Perhaps you find this barrage of general-purpose functions exhausting, but it's an artefact of a design philosophy of the F# language. The F# base library contains only few general-purpose functions. Contrast this with GHC's base library, which comes with all of these functions built in.

The new function is like Result.cata, but over Async<Result<_>>.

// ('a -> 'b) -> ('c -> 'b) -> Async<Result<'a,'c>> -> Async<'b> let cata f g r = async { let! r' = r return Result.cata f g r' }

Since this function does conceptually the same as Result.cata I decided to retain the name cata and just put it in the AsyncResult module. (This may not be strictly correct, as I haven't really given a lot of thought to what a catamorphism for Async would look like, if one exists. I'm open to suggestions about better naming. After all, cata is hardly an idiomatic F# name.)

With AsyncResult.cata you can now compose the system:

let sut pid r = async { let! p = AsyncOption.traverse (twoFA.VerifyProof r.Mobile) pid let! res = completeRegistrationWorkflow p r return! res |> AsyncResult.traverseBoth db.CompleteRegistration twoFA.CreateProof |> AsyncResult.cata (fun () -> RegistrationCompleted) ProofRequired }

Not only did the call to completeRegistrationWorkflow get even simpler, but you also now avoid the awkwardly named pidr value. Thanks to the let! binding, res has the type Result<Registration, Mobile>.

Note that you can now let both impure actions (db.CompleteRegistration and twoFA.CreateProof) traverse the result. This step produces an Async<Result<unit, ProofId>> that's immediately piped to AsyncResult.cata. This reduces the two alternative dimensions of the Result to a single Async<CompleteRegistrationResult> value.

The completeRegistrationWorkflow function now begs to be further simplified.

Pure registration workflow #

Once you remove all dependencies, your domain logic doesn't have to be asynchronous. Nothing asynchronous happens in completeRegistrationWorkflow, so simplify it:

let completeRegistrationWorkflow (proof: bool option) (registration: Registration) : Result<Registration, Mobile> = match proof with | None -> Error registration.Mobile | Some isValid -> if isValid then Ok registration else Error registration.Mobile

Gone is the async computation expression, including the return keyword. This is now a pure function.

You'll have to adjust the composition once more, but it's only a minor change:

let sut pid r = async { let! p = AsyncOption.traverse (twoFA.VerifyProof r.Mobile) pid return! completeRegistrationWorkflow p r |> AsyncResult.traverseBoth db.CompleteRegistration twoFA.CreateProof |> AsyncResult.cata (fun () -> RegistrationCompleted) ProofRequired }

The result of invoking completeRegistrationWorkflow is no longer an Async value, so there's no reason to let!-bind it. Instead, you can call it and immediately pipe its output to AsyncResult.traverseBoth.

DRY #

Consider completeRegistrationWorkflow. Can you make it simpler?

At this point it should be evident that two of the branches contain duplicate code. Applying the DRY principle you can simplify it:

let completeRegistrationWorkflow (proof: bool option) (registration: Registration) : Result<Registration, Mobile> = match proof with | Some true -> Ok registration | _ -> Error registration.Mobile

I'm not too fond of this style of type annotation for simple functions like this, so I'd like to remove it:

let completeRegistrationWorkflow proof registration = match proof with | Some true -> Ok registration | _ -> Error registration.Mobile

These two steps are pure refactorings: they only reorganise the code that implements completeRegistrationWorkflow, so the composition doesn't change.

Essential complexity #

While reading this article, you may have felt frustration gather. This is cheating! You took out all of the complexity. Now there's nothing left! You're likely to feel that I've moved a lot of behaviour into untestable code. I've done nothing of the sort.

I'll remind you that while functions like AsyncOption.traverse and AsyncResult.cata do contain branching behaviour, they can be tested. In fact, since they're pure functions, they're intrinsically testable.

It's true that a composition of a pure function with its impure dependencies may not be (unit) testable, but that's also true for a Dependency Injection-based object graph composed in a Composition Root.

Compositions of functions may look non-trivial, but to a degree, the type system will assist you. If your composition compiles, it's likely that you've composed the impure/pure/impure sandwich correctly.

Did I take out all the complexity? I didn't. There's a bit left; the function now has a cyclomatic complexity of two. If you look at the original function, you'll see that the duplication was there all along. Once you remove all the accidental complexity, you uncover the essential complexity. This happens to me so often when I apply functional programming principles that I fancy that functional programming is a silver bullet.

Pipeline composition #

We're mostly done now. The problem now appears in all its simplicity, and you have an impure/pure/impure sandwich.

You can still improve the code, though.

If you consider the current composition, you may find that p isn't the best variable name. I admit that I struggled with naming that variable. Sometimes, variable names are in the way and the code might be clearer if you could elide them by composing a pipeline of functions.

That's always worth an attempt. This time, ultimately I find that it doesn't improve things, but even an attempt can be illustrative.

If you want to eliminate a named value, you can often do so by piping the output of the function that produced the variable directly to the next function. This does, however, require that the function argument is the right-most. Currently, that's not the case. registration is right-most, and proof is to the left.

There's no compelling reason that the arguments should come in that order, so flip them:

let completeRegistrationWorkflow registration proof = match proof with | Some true -> Ok registration | _ -> Error registration.Mobile

This enables you to write the entire composition as a single pipeline:

let sut pid r = async { return! AsyncOption.traverse (twoFA.VerifyProof r.Mobile) pid |> Async.map (completeRegistrationWorkflow r) |> Async.bind ( AsyncResult.traverseBoth db.CompleteRegistration twoFA.CreateProof >> AsyncResult.cata (fun () -> RegistrationCompleted) ProofRequired) }

This does, however, call for two new general-purpose functions: Async.map and Async.bind:

// ('a -> 'b) -> Async<'a> -> Async<'b> let map f x = async { let! x' = x return f x' } // ('a -> Async<'b>) -> Async<'a> -> Async<'b> let bind f x = async { let! x' = x return! f x' }

In my opinion, these functions ought to belong to F#'s Async module, but for for reasons that aren't clear to me, they don't. As you can see, though, they're easy to add.

While the this change gets rid of the p variable, I don't think it makes the overall composition easier to understand. The action of swapping the function arguments does, however, enable another simplification.

Eta reduction #

Now that proof is completeRegistrationWorkflow's last function argument, you can perform an eta reduction:

let completeRegistrationWorkflow registration = function | Some true -> Ok registration | _ -> Error registration.Mobile

Not everyone is a fan of the point-free style, but I like it. YMMV.

Sandwich #

Regardless of whether you prefer completeRegistrationWorkflow in point-free or pointed style, I think that the composition needs improvement. It should explicitly communicate that it's an impure/pure/impure sandwich. This makes it necessary to reintroduce some variables, so I'm also going to bite the bullet and devise some better names.

let sut pid r = async { let! validityOfProof = AsyncOption.traverse (twoFA.VerifyProof r.Mobile) pid let decision = completeRegistrationWorkflow r validityOfProof return! decision |> AsyncResult.traverseBoth db.CompleteRegistration twoFA.CreateProof |> AsyncResult.cata (fun () -> RegistrationCompleted) ProofRequired }

Instead of p, I decided to call the first value validityOfProof. This is the result of the first impure action in the sandwich (the upper slice of bread).

While validityOfProof is the result of an impure action, the value itself is pure and can be used as input to completeRegistrationWorkflow. This is the pure part of the sandwich. I called the output decision because the workflow makes a decision based on its input, and it's up to the caller to act on that decision.

Notice that decision is bound with a let binding (instead of a let! binding), despite taking place inside an async workflow. This is because completeRegistrationWorkflow is pure. It doesn't return an Async value.

The second impure action acts on decision through a pipeline of AsyncResult.traverseBoth and AsyncResult.cata, as previously explained.

I think that the impure/pure/impure sandwich is more visible like this, so that was my final edit. I'm happy with how it looks now.

Conclusion #

I don't claim that you can always refactor code to an impure/pure/impure sandwich. In fact, I can easily envision categories of software where such an architecture seems impossible.

Still, I find it intriguing that when I find myself in the realm of web services or message-based applications, I can't recall a case where a sandwich has been impossible. Surely, there must cases where it is so. That's the reason that I solicit examples. This article was a response to such an example. I found it fruitful, because it enabled me to discuss several useful techniques for composing behaviour in a functional architecture. On the other hand, it failed to be a counter-example.

I'm sure that some readers are left with a nagging doubt. That's all very impressive, but would you actually write code like that in a piece of production software?

If it was up to me, then: yes. I find that when I can keep code pure, it's trivial to unit test and there's no test-induced damage. Functions also compose in a way objects don't easily do, so there's many advantages to functional programming. I'll take them when they're available.

As always, context matters. I've been in team settings where other team members would embrace this style of programming, and in other environments where team members wouldn't understand what was going on. In the latter case, I'd adjust my approach to challenge, not alienate, other team members.

My intention with this article was to show what's possible, not to dictate what you should do. That's up to you.

This article is the December 2 entry in the F# Advent Calendar in English 2019.

Comments

Thank you so much for the comprehensive reply to my comment. It was very instructive to see refactoring process, from thought to code. The post is an excellent reply to the question I asked.

A slight modification

In my original comment, I made one simplification that, in hindsight, I perhaps should not have made. It is not critical, but it complicates things slightly. In reality, the

completeRegistrationfunction does not returnAsync<unit>, butAsync<Result<unit, CompleteRegistrationError>>(where, currently,CompleteRegistrationErrorhas the single caseUserExists, returned if the DB throws a unique constraint error).As I see it, the impact of this to your refactoring is two-fold:

AsyncResult.traverseBoth, since the signatures between the two cases aren't compatible (unless you want to mess around with nestedResultvalues). You could write a customtraversefunction just for the needed signature, but then we’ve traveled well into the lands of “generic does not imply general”.Resultbeing reserved for actual errors.Evaluating the refactoring

My original comment ended in the following question (emphasis added):

With this (vague) question and the above modifications in mind, let's look at the relevant code before/after. In both cases, there are two functions: The workflow/logic, and the composition.

Before

Before refactoring, we have a slightly complex impure workflow (which still is fairly easily testable using state-based testing, as you so aptly demonstrated) – note the

asyncResultCE (I’m using the excellent FsToolkit.ErrorHandling, if anyone wonders) and the updated signatures; otherwise it’s the same:Secondly, we have the trivial "humble object" composition, which looks like this:

The composition is, indeed, humble – the only thing it does is call the higher-order workflow function with the correct parameters. It has no cyclomatic complexity and is trivial to read, and I don't think anyone would consider it necessary to test.

After

After refactoring, we have the almost trivial pure function we extracted (for simplicity I let it return

Resulthere, as you proposed):Secondly, we have the composition function. Now, with the modification to

completeRegistration(returningAsync<Result<_,_>>), it can't as easily be written in point-free style. You might certainly be able to improve it, but here is my quick initial take.Evaluation

Now that we have presented the code before/after, let us take stock of what we have gained and lost by the refactoring.

Pros:

Cons:

AsyncOption.traverse,AsyncResult.traverseBoth,AsyncResult.cata, etc.Returning to my initial question: Does the refactoring “reduce complexity where it matters?“ I’m not sure. This is (at least partly) “personal opinions” territory, of course, and my vague question doesn’t help. But personally I find the result of the refactoring more complex to understand than the original, DI workflow-based version.

Based on Scott Wlaschin’s book Domain Modelling Made Functional, it’s possible he might agree. He seems very fond of the “DI workflow” approach there. I personally prefer a bit more dependency rejection than that, because I find “DR”/sandwiches often leads to simpler code, but in this particular case, I may prefer the impure DI workflow, tested using state-based testing. At least for the more complex code I described, but perhaps also for your original example.

Still, I truly appreciate your taking the time to respond in this manner. It was very instructive, as always, which was after all the point. And you’re welcome to share any insights regarding this comment, too.

Christer, thank you for writing. This is great! One of your comments inspires me to compose another article that I've long wanted to write. If I manage to produce it in time, I'll publish it Monday. Once that's done, I'll respond here in a more thorough manner.

When I do that, however, I don't plan to reproduce your updated example, or address it in detail. I see nothing in it that invalidates what I've already written. As far as I can tell, you don't need to explicitly pattern-match on

completePure reg proofValidity. You should be able to map or traverse over it like already shown. If you want my help with the details, I'll be happy to do so, but then please prepare a minimal working example like I did for this article. You can either fork my example or make a new repository.This is a fantastic post Mark! Thank you very much for going step-by-step while explaining how you refactored this code.

I would like to suggest a example in the realm of web services or message-based applications that cannot be expressed as a impure/pure/impure sandwich.

Let's call an "impure/pure/impure sandwich" an impure-pure-impure composition. More generally, any impure funciton can be expressed as a composition of the form

[pure-]impure(-pure-impure)*[-pure]. That is, (1) it might begin with a pure step, then (2) there is an impure step, then (3) there is a sequence of length zero or more containing a pure step followed by an impure step, and lastly (4) it might end with another pure step. One reason an impure fucntion might intentially be expressed by a composition that ends with a pure step is to erase senitive informaiton form the memory hierarchy. For simplicity though, let's assume that any impure function can be refactored so that the corresponding composition ends with an impure step. Let the length of a composition be one plus the number of dashes (-) that it contains.Suppose

fis a function with an impure-pure-impure composition such thatfcannot be refactored to a fucntion with a composition of a smaller length. Then there exists fucntionf'with a pure-impure-pure-impure composition. The construction uses public-key cryptography. I think this is a natural and practical example.Here is the definition of

f'in words. The user sends to the server ciphertext encryped using the server's public key. The user's request is received by a process that already has the server's private key loaded into memory. This process decrypts the user's ciphertext using its private key to obtain some plantextp. This step is pure. Then the process passespintof.Using symmetric-key cryptography, it is possible to construct a function with a composition of an arbitrarily high length. The following construction reminds me of how union routing works (though each decryption in that case is intended to happen in a different process on a different server). I admit that this example is not very natural or practical.

Suppose

fis a function with a composition of lengthn. Then there exists fucntionf'with a composition of length greater thann. Specifically, if the original composition starts with a pure step, then the length is larger by one; if the original composition starts with an impure step, then the length is larger by two.Here is the definition of

f'in words. The user sends to the server an ID and ciphertext encryped using a symmetric key that corresponds to the ID. The user's request is received by a process that does not have any keys loaded into memory. First, this process obtains from disk the appropriate symmetric key using the ID. This step is impure. Then this process decrypts the user's ciphertext using this key to obtain some plantextp. This step is pure. Then the process passespintof.Tyson, thank you for writing. Unfortunately, I don't follow your chain of reasoning. Cryptography strikes me as fitting the impure/pure/impure sandwich architecture quite well. There's definitely an initial impure step because you have to initialise a random number generator, as well as load keys, salts, and whatnot from storage. From there, though, the cryptographic algorithms are, as far as I'm aware, pure calculation. I don't see how asymmetric cryptography changes that.

The reason that I'm soliciting examples that defy the impure/pure/impure sandwich architecture, however, is that I'm looking for a compelling example. What to do when the sandwich architecture is impossible is a frequently asked question. To be clear, I know what to do in that situation, but I'd like to write an article that answers the question in a compelling way. For that, I need an example that an uninitiated reader can follow.

Sorry that my explanation was unclear. I should have included an example.

I agree that cyptographic algorithms are pure. From your qoute that I included above, I get the impression that you have neglected to consider what computation is to be done with the output of the cyptogrpahic algorithm.

Here is a specific example of my first construction, which uses public-key cyptography. Consider the function

sutthat concluded your post. I repeat it for clarity.Let

sutbe the functionfin that construction. In particular,sutis an impure/pure/impure sandwich, or equivalently an impure-pure-impure composition that of course has length 3. Furthermore, I think it is clear that this behavior cannot be expressed as a pure-impure-pure composition, a pure-impure composition, an impure-pure composition, or an impure composition. You worked very hard to simplfy that code, and I believe an implicit claim of yours is that it cannot be simplified any further.In this case,

f'would be the following function.As I defined it, this function is a pure-impure-pure-impure composition, which has length 4. Maybe in your jargon you would call this a pure/impure/pure/impure sandwich. My claim is that this function cannot be refactored into an impure/pure/impure sandwich.

Do you think that my claim is correct?

Tyson, thank you for your patience with me. Now I get it. As stated, your composition looks like a pure-impure-pure-impure composition, but unless you hard-code

privateKey, you'll have to load that value, which is an impure operation. That would make it an impure-pure-impure-pure-impure composition.The decryption step itself is an impure-pure composition, assuming that we need to load keys, salts, etc. from persistent storage. You might also want to think of it as a 'mostly' pure function, since you could probably load decryption keys once when the application process starts, and keep them around for its entire lifetime.

It's a correct example of a more involved interaction model. Thank you for supplying it. Unfortunately, it's not one I can use for an article. Like other cross-cutting concerns like caching, logging, retry mechanisms, etcetera, security can be abstracted away as middleware. This implies that you'd have a middleware action that's implemented as an impure-pure-impure sandwich, and an application feature that's implemented as another impure-pure-impure sandwich. These two sandwiches are unrelated. A change to one of them is unlikely to trigger a change in the other. Thus, we can still base our application architecture on the notion of the impure-pure-impure sandwich.

I hope I've explained my demurral in a sensible way.

The are unrelated semantically. Syntatically, the whole application sandwich is the last piece of impure bread on the middleware sandwich. This reminds me of a thought I have had and also heard recently, which is that the structure of code is like a fractal.

Anyway, I am hearing you say that you want functions to have "one responsibility", to do "one thing", to change for "one reason". With that constraint satisfied, you are requesting an example of a funciton that is not an impure/pure/impure sandwich. I am up to that challenge. Here is another attempt.

Suppose our job is to implement a man-in-the-middle attack in the style of Schneier's Chess Grandmaster Problem in which Alice and Bob know that they are communicating with Malory while Malory simply repeats what she hears to the other person. Specifically, Alice is a client and Bob is a server. Mailory acts like a server to Alice and like a client to Bob. The funciton would look something like this.

This is a pure-impure-pure composition, which is different from an impure-pure-impure composition.

Tyson, thank you for writing. The way I understand it, we are to assume that both

convertIncomingandconvertOutgoingare complicated functions that require substantial testing to get right. Under that assumption, I think that you're right. This doesn't directly fit the impure-pure-impure sandwich architecture.It does, however, fit a simple function composition. As far as I can see, it's equivalent to something like this:

let malroyInTheMiddle = Async.fromResult >> Async.map convertIncoming >> Async.bind service >> Async.map convertOutgoingI haven't tested it, but I'd imagine it to be something like that.

To nitpick, this isn't a pure-impure-pure composition, but rather an impure-pure-impure-pure-impure composition. The entry point of a system is always impure, as is the output.

Christer, I'd hoped that I'd already addressed some of your concerns in the article itself, but I may not have done a good enough job of it. Overall, given a question like

I tend to put emphasis on is it possible. Not that the rest of the question is unimportant, but it's more subjective. Perhaps you find that my article didn't answer your question, but I hope at least that I managed to establish that, yes, it's possible to refactor to an impure-pure-impure sandwich.Does it matter? I think it does, but that's subjective. I do think, though, that I can objectively say that my refactoring is functional, whereas passing impure functions as arguments isn't. Whether or not an architecture ought to be functional is, again, subjective. No-one says that it has to be. That's up to you.

As I wrote in my preliminary response, I'm not going to address your modification. I don't see that it matters. Even when you return an

Async<Result<_,_>>you canmap,bind, ortraverseover it. You may not be able to useAsyncResult.traverseBoth, but you can derive specialisations likeAsyncResult.traverseOkandAsyncResult.traverseError.First, like you did, I find it illustrative to juxtapose the alternatives. I'm going to use the original example first:

In contrast, here's my refactoring:

It's true that my composition (

sut) seems more involved than yours, but the overall trade-off looks good to me. In total, the code is simpler.In your evaluation, you make some claims that I'd like to specifically address. Most are reasonable, but I think a few require special attention:

Indeed. This should be listed as a pro, not a con. Whether or not it's worth it is a different discussion.As I wrote in the article:

(Emphasis from the original.) Isn't it always worth it to take away accidental complexity? No, it doesn't. It has a cyclomatic complexity of 1, exactly like the original humble object. True, but neither can the original humble object. According to which criterion? It has the same cyclomatic complexity, but I admit that more characters went into typing it. On the other hand, the composition juxtaposed with the actual function has far fewer characters than the original example.You also write that

I don't like the epithet non-standard. It's true that these functions aren't inFSharp.Core, for reasons that aren't clear to me. In comparison, they're part of the standardbaselibrary in Haskell.There's nothing non-standard about functions like these. Like

mapandbind, traversals and catamorphisms are universal abstractions. They exist independently of particular programming languages or library packages.I think that it's fair criticism that they may not be friendly to absolute beginners, but they're still fairly basic ideas that address real needs. The same can be said for the

asyncResultcomputation expression that you've decided to use. It's also 'non-standard' only in the sense that it's not part ofFSharp.Core, but otherwise standard in that it's just a stack of monads, and plenty of libraries supply that functionality. You can also write that computation expression yourself in a dozen lines of code.In the end, all of this is subjective. As I also wrote in my conclusion:

What I do, however, think is important to realise is that what I suggest is to learn a set of concepts once. Once you understand functors, monads, traversals etcetera, that's knowledge that applies to F#, Haskell, C#, JavaScript (I suppose) and so on.Personally, I find it a better investment of my time to learn a general concept once, and then work with trivial code, rather than having to learn, over and over again, how to deal with each new code base's accidental complexity.

Mark, thank you for getting back to me with a detailed response.

First, a general remark. I see that my comment might have been a bit "sharp around the edges” and phrased somewhat carelessly, giving the impression that I was not happy with your treatment of my example. I’d just like to clearly state that I am. You replied in your usual clear manner to exactly the question I posed, and seeing your process and solution was instructive for me.

We are all learning, all the time, and if I use a strong voice, that is primarily because strong opinions, weakly held often seems to be a fruitful way to drive discussion and learning.

With that in mind, allow me to address some of your remarks and possibly soften my previous comment.

Your article did indeed answer my question. My takeaway (then, not necessarily now after reading the rest of your comment) was that you managed to refactor to impure-pure-impure at the "expense” of making the non-pure part harder to understand. But as you say, that’s subjective, and your remarks on that later in your comment was a good point of reflection for me. I’ll get to that later.

I agree on all points.

I don’t agree 100% that it’s a completely fair comparison, since you’re leaving out the implementations of

AsyncOption.traverse,AsyncResult.traverseBoth, andAsyncResult.cata. However, I get why you are doing it. These are generic utility functions for universal concepts that, as you say later in your comment, you “learn once”. In that respect, it’s fair to leave them out. My only issue with it is that since F# doesn’t have higher-kinded types, these utility functions have to be specific to the monads and monad stacks in use. I originally thought this made such functions less understandable and less useful, but after reading the rest of your comment, I’m not sure they are. More on that below.(Emphasis yours.) Just in case: “Evaluation” might have been a poor choice of words. I hope you did not take it to mean that I was a teacher grading a student’s test. This was not in any way intended personally (e.g. evaluating "your solution”). I was merely looking to sum up my subjective opinions about the refactoring.

I find it hard to say an unequivocal "yes” to such general statements. Ultimately it depends on the specific context and tradeoffs involved. If the context is “a codebase to be used for onboarding new F# devs” and the tradeoffs are “use generic helper functions to traverse bifunctors in a stack of monads”, then I’m not sure. (It may still be, but it’s certainly not a given.)

But generally, though I haven’t reflected deeply on this, I’m sure you’re right that it’s worthwhile to always take away accidental complexity.

You’re right. Thank you for the clarifying article on cyclomatic complexity.

That’s correct, but my point was that the original composition was trivial (just calling a “DI function” with the correct arguments/dependencies) and didn’t need to be tested, whereas the refactored composition does more and might warrant testing (at least to a larger degree than the original).

This raises an interesting point. It seems (subjectively to me based on what I’ve read) to be a general consensus that a function can be left untested (is “humble”, so to speak) as long as it consists of just generic helpers, like the refactored composition. That "if it compiles, it works”. This is not a general truth, since for some signatures there may exist several transformations from the input type to the output type, where the output value is different for the different transformations. I have come across such cases, and even had bugs because I used the wrong transformation. Which is why I said:

It is more complex in the sense that it doesn’t just call a function with the correct dependencies. The original composition is more or less immediately recognizable as correct. The refactored composition, as I said, required me to look at it more carefully to convince myself that it was correct. (I will grant that this is to some extent subjective, though.)

This is the primary point of reflection for me in your comment. While I frequently use monads and monad stacks (particularly

Async<Result<_,_>>) and often write utility code to transform when needed (e.g.List.traverseResult), I try to limit the number of such custom utility functions. Why? I’m not sure, actually. It may very well have to do with my work environment, where for a long time I have been the only F# dev and I don’t want to alienate the other .NET devs before they even get started with F#.In light of your comment, perhaps F# devs are doing others a disservice if we limit our use of important, general concepts like functors, monads, traversals etc.? Then again, there’s certainly a balance to be struck. I got started (and thrilled) with F# by reading F# for fun and profit and learning about algebraic types, the concise syntax, "railway-oriented programming” etc. If my first glimpse of F# had instead been

AsyncSeq.traverseAsyncResultOption, then I might never have left the warm embrace of C#.I might check out FSharpPlus, which seems to make this kind of programming easier. I have previously steered away from that library because I deemed it “too complex” (c.f. my remarks about alienating coworkers), but it might be time to reconsider. If you have tried it, I would love to hear your thoughts on it in some form or another, though admittedly that isn’t directly related to the topic at hand.

Christer, don't worry about the tone of the debate. I'm not in the least offended or vexed. On the contrary, I find this a valuable discussion, and I'm glad that we're having it in a medium where it's also visible to other people.

I think that we're gravitating towards consensus. I definitely agree that the changes I suggest aren't beginner-friendly.

People sometimes ask me for advice on how to get started with functional programming, and I always tell .NET developers to start with F#. It's a friendly language that enables everyone to learn gradually. If you already know C# (or Visual Basic .NET) the only thing you need to learn about F# is some syntax. Then you can write object-oriented F#. As you learn new functional concepts, you can gradually change the way you write F# code. That's what I did.

I agree with your reservations about onboarding and beginner-friendliness. When that's a concern, I wouldn't write the F# code like I suggested either.

For a more sophisticated team, however, I feel that my suggestions are improvements that matter. I grant you that the composition seems more convoluted, but I consider the overall trade-off beneficial. In the terminology suggested by Rich Hickey, it may not be easier, bit it's simpler.

I have no experience with FSharpPlus or any similar libraries. I usually just add the monad stacks and functions to my code base on an as-needed basis. As we've seen here, such functions are mostly useful to compose other functions, so they rarely need to be exported as part of a code base's surface area.