The Maître d' kata by Mark Seemann

A programming kata.

I recently wrote about doing programming katas. You can find katas in many different places. Some sites exist exclusively for that purpose, such as the Coding Dojo or CodeKata. In other cases, you can find individual katas on blogs; one of my favourites is the Diamond kata. You can also lift exercises from other sources and treat them as katas. For example, I recently followed Mike Hadlow's lead and turned a job applicant test into a programming exercise. I've also taken exercises from books and repurposed them. For example, I've implemented the Graham Scan algorithm for finding convex hulls a couple of times.

In this article, I'll share an exercise that I've found inspiring myself. I'll call it the Maître d' kata.

I present no code in this article. Part of what makes the exercise interesting, I think, is to figure out how to model the problem domain. I will, however, later publish one of my attempts at the kata.

Problem statement #

Imagine that you're developing an online restaurant reservation system. Part of the behaviour of such a system is to decide whether or not to accept a reservation. At a real restaurant, employees fill various roles required to make it work. In a high-end restaurant, the maître d' is responsible for taking reservations. I've named the kata after this role. If you're practising domain-driven design, you might want to name your object, class, or module MaîtreD or some such.

The objective of the exercise is to implement the MaîtreD decision logic.

Reservations are accepted on a first-come, first-served basis. As long as the restaurant has available seats for the desired reservation, it'll accept it.

A reservation contains, at a minimum, a date and time as well as a positive quantity. Here's some examples:

| Date | Quantity |

| August 8, 2050 at 19:30 | 3 |

| November 27, 2022 at 18:45 | 4 |

| February 27, 2014 at 13:22 | 12 |

Notice that dates can be in your future or past. You might want to assume that the maître d' would reject reservations in the past, but you can't assume when the code runs (or ran), so don't worry about that. Notice also that quantities are positive integers. While a quantity shouldn't be negative or zero, it could conceivably be large. I find it realistic, however, to keep quantities at low two-digit numbers or less.

A reservation will likely contain other data, such as the name of the person making the reservation, contact information such as email or phone number, possibly also an ID, and so on. You may add these details if you want to make the exercise more realistic, but they're not required.

I'm going to present one feature requirement at a time. If you read the entire article before you do the exercise, it'd correspond to gathering detailed requirements before starting to code. Alternatively, you could read the first requirement, do the exercise, read the next requirement, refactor your code, and so on. This would simulate a situation where your organisation gradually uncovers how the system ought to work.

Boutique restaurant #

As readers of my book may have detected, I'm a foodie. Some years ago I ate at Blanca in Brooklyn. That restaurant has one communal bar where everyone sits. There was room for twelve people, and dinner started at 19:00 whether you arrived on time or not. Such restaurants actually exist. It's an easy first step for the kata. Assume that the restaurant is only open for dinner, has no second seating, and a single shared table. This implies that the time of day of reservations doesn't matter, while the date still matters. Some possible test cases could be:

| Table size | Existing reservations | Candidate reservation | Expected outcome |

| 12 | none | Quantity: 1 | Accepted |

| 12 | none | Quantity: 13 | Rejected |

| 12 | none | Quantity: 12 | Accepted |

| 4 | Quantity: 2, Date: 2023-09-14 | Quantity: 3, Date: 2023-09-14 | Rejected |

| 10 | Quantity: 2, Date: 2023-09-14 | Quantity: 3, Date: 2023-09-14 | Accepted |

| 10 |

Quantity: 3, Date: 2023-09-14 Quantity: 2, Date: 2023-09-14 Quantity: 3, Date: 2023-09-14 |

Quantity: 3, Date: 2023-09-14 | Rejected |

| 4 | Quantity: 2, Date: 2023-09-15 | Quantity: 3, Date: 2023-09-14 | Accepted |

This may not be an exhaustive set of test cases, but hopefully illustrates the desired behaviour. Try using the Devil's Advocate technique or property-based testing to identify more test cases.

Haute cuisine #

The single-shared-table configuration is unusual. Most restaurants have separate tables. High-end restaurants like those on the World's 50 best list, or those with Michelin stars often have only a single seating. This is a good expansion of the domain logic.

Assume that a restaurant has several tables, perhaps of different sizes. A table for four will seat one, two, three, or four people. Once a table is reserved, however, all the seats at that table are reserved. A reservation for three people will occupy a table for four, and the redundant seat is wasted. Obviously, the restaurant wants to maximise the number of guests, so it'll favour reserving two-person tables for one and two people, four-person tables for three and four people, and so on.

In order to illustrate the desired behaviour, here's some extra test cases to add to the ones already in place:

| Tables | Existing reservations | Candidate reservation | Expected outcome |

|

Two tables for two Two tables for four |

none | Quantity: 4, Date: 2024-06-07 | Accepted |

|

Two tables for two Two tables for four |

none | Quantity: 5, Date: 2024-06-07 | Rejected |

|

Two tables for two One table for four |

Quantity: 2, Date: 2024-06-07 | Quantity: 4, Date: 2024-06-07 | Accepted |

|

Two tables for two One table for four |

Quantity: 3, Date: 2024-06-07 | Quantity: 4, Date: 2024-06-07 | Rejected |

Again, you should consider adding more test cases if you're unit-testing the kata.

Second seatings #

Some restaurants (even some of those on the World's 50 best list) have a second seating. As a diner, you have a limited time (e.g. 2½ hours) to complete your meal. After that, other guests get your table.

This implies that you must now consider the time of day of reservations. You should also be able to use an arbitrary (positive) seating duration. All previous rules should still apply. New test cases include:

| Seating duration | Tables | Existing reservations | Candidate reservation | Expected outcome |

| 2 hours |

Two tables for two One table for four |

Quantity: 4, Date: 2023-10-22, Time: 18:00 | Quantity: 3, Date: 2023-10-22, Time: 20:00 | Accepted |

| 2½ hours |

One table for two Two tables for four |

Quantity: 2, Date: 2023-10-22, Time: 18:00 Quantity: 1, Date: 2023-10-22, Time: 18:15 Quantity: 2, Date: 2023-10-22, Time: 17:45 |

Quantity: 3, Date: 2023-10-22, Time: 20:00 | Rejected |

| 2½ hours |

One table for two Two tables for four |

Quantity: 2, Date: 2023-10-22, Time: 18:00 Quantity: 2, Date: 2023-10-22, Time: 17:45 |

Quantity: 3, Date: 2023-10-22, Time: 20:00 | Accepted |

| 2½ hours |

One table for two Two tables for four |

Quantity: 2, Date: 2023-10-22, Time: 18:00 Quantity: 1, Date: 2023-10-22, Time: 18:15 Quantity: 2, Date: 2023-10-22, Time: 17:45 |

Quantity: 3, Date: 2023-10-22, Time: 20:15 | Accepted |

If you make the seating duration short enough, you may even make room for a third seating, and so on.

Alternative table configurations #

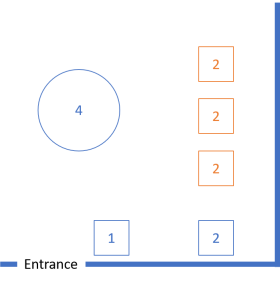

If tables are rectangular, the restaurant has the option to combine several smaller tables into one larger. Consider a typical restaurant layout like this:

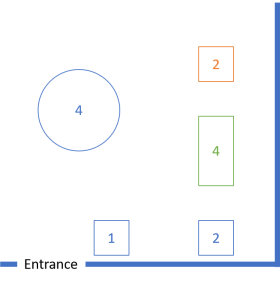

There's a round four-person table, as well as a few small tables that can't easily be pushed together. There's also three (orange) two-person tables where one guest sits against the wall, and the other diner faces him or her. These can be used as shown above, but the restaurant can also push two of these tables together to accommodate four people:

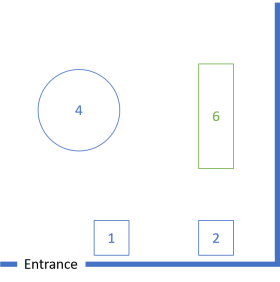

This still leaves one of the adjacent two-person tables as an individual table, but the restaurant can also push all three tables together to accommodate six people:

Implement decision logic that allows for alternative table configurations. Remember to take seating durations into account. Consider both the configuration illustrated, as well as other configurations. Note that in the above configuration, not all two-person tables can be combined.

More domain logic #

You can, if you will, invent extra rules. For example, restaurants have opening hours. A restaurant that opens at 18:00 and closes at 0:00 will not accept reservations for 13:30, regardless of table configuration, existing reservations, seating duration, and so on.

Building on that idea, some restaurants have different opening hours on various weekdays. Some are closed Mondays, serve dinner only Tuesday to Friday, but are then open for both lunch and dinner in the weekend.

Going in that direction, however, opens a can of worms. Perhaps the restaurant is closed on public holidays. Or perhaps it's explicitly open on public holidays, to cater for an audience that may not otherwise dine out. But implementing a holiday calender is far from as simple as it sounds. That's the reason I left such rules out of the above specifications of the kata.

Another idea that you may consider is to combine communal bar seating with more traditional tables. The Clove Club is an example of restaurant that does it that way.

Summary #

This is a programming kata description. Implement the decision logic of a maître d': Can the restaurant accept a given reservation?

After some time has gone by, I'll post at least one of my own attempts. You're welcome to leave a comment if you do the kata and wish to share your results.