ploeh blog danish software design

Auto-mocking Container

A unit test pattern

This article describes a unit test pattern called an Auto-mocking Container. It can be used as a solution to the problem:

How can unit tests be decoupled from Dependency Injection mechanics?

By using a heuristic composition engine to compose dynamic Test Doubles into the System Under Test

A major problem with unit tests is to make sure that they are robust in the face of a changing system. One of the most common problems programmers have with unit tests is the so-called Fragile Test smell. Every time you attempt to refactor your code, tests break.

There are various reasons why that happens and the Auto-mocking Container pattern does not help in all cases, but a common reason that tests break is when you change the constructor of your System Under Test (SUT). In such cases, the use of an Auto-mocking Container can help.

How it works #

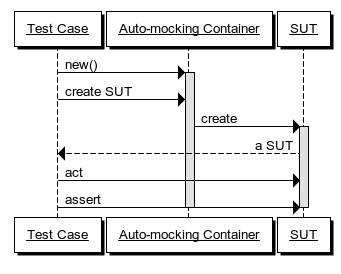

In order to decouple a unit test from the mechanics of creating an instance of the SUT, the test code can repurpose a Dependency Injection (DI) Container to compose it. The DI Container must be customizable to the extent that it can automatically compose dynamic Test Doubles (mocks/stubs) into the SUT.

It's important to notice that this technique is a pure unit testing concern. Even if you use an Auto-mocking Container in your unit test, you don't have to use a DI Container in your production code - or you can use a different DI Container than the one you've chosen to repurpose as an Auto-mocking Container.

When a test case wants to exercise the SUT, it needs an instance of the SUT. Instead of creating the SUT directly by invoking its constructor, the test case uses an Auto-mocking Container to create the SUT instance. The Auto-mocking Container automatically supplies dynamic mocks in place of all the SUT's dependencies, freeing the test writer from explicitly dealing with this concern.

This decouples each test case from the mechanics of how the SUT is created, making the test more robust. Even if the SUT's constructor is refactored, the test case remains unimpacted because the Auto-mocking Container dynamically deals with the changed constructor signature.

When to use it #

Use an Auto-mocking Container when you are unit testing classes which utilize DI (particularly Constructor Injection). In a fully loosely coupled system, constructors are implementation details, which means that you may decide to change constructor signatures as part of refactoring.

Particularly early in a code base's lifetime, the system and its internal design may be in flux. In order to enable refactoring, it's important to be able to change constructor signatures without worrying about breaking tests. In such cases, an Auto-mocking Container can be of great help.

In well-established code bases, introducing an Auto-mocking Container is unlikely to be of much benefit, as the code is assumed to be more stable.

Auto-mocking Containers are also less ideally suited for code-bases which rely more on a functional programming style with Value Objects and data flow algorithms, and less on DI.

Implementation details #

Use an existing DI Container, but repurpose it as an Auto-mocking Container. Normal DI Containers don't serve dynamic mock objects by default, so you'll need to pick a DI Container which is sufficiently extensible to enable you to change its behavior as desired.

In order to extend the DI Container with the ability to serve dynamic mock objects, you must also pick a suitable dynamic mock library. The Auto-mocking Container is nothing more than a 'Glue Library' that connects the behavior of the DI Container with the behavior of the dynamic mock library.

Some open source projects exist that provide pre-packaged Glue Libraries as Auto-mocking Containers by combining two other libraries, but with good DI Containers and dynamic mock libraries, it's a trivial effort to produce the Auto-mocking Container as part of the unit test infrastructure.

Motivating example #

In order to understand how unit tests can become tightly coupled to the construction mechanics of SUTs, imagine that you are developing a simple shopping basket web service using Test-Driven Development (TDD).

To keep the example simple, imagine that the shopping basket is going to be a CRUD service exposed over HTTP. The framework you've chosen to use is based on the concept of a Controller that handles incoming requests and serves responses. In order to get started, you write the first (ice breaker) unit test:

[Fact] public void SutIsController() { var sut = new BasketController(); Assert.IsAssignableFrom<IHttpController>(sut); }

This is a straight-forward unit test which prompts you to create the BasketController class.

The next thing you want to do is to enable clients to add new items to the basket. In order to do so, you write the next test:

[Fact] public void PostSendsCorrectEvent() { var channelMock = new Mock<ICommandChannel>(); var sut = new BasketController(channelMock.Object); var item = new BasketItemModel { ProductId = 1234, Quantity = 3 }; sut.Post(item); var expected = item.AddToBasket(); channelMock.Verify(c => c.Send(expected)); }

In order to make this test compile you need to add this constructor to the BasketController class:

private ICommandChannel channel; public BasketController(ICommandChannel channel) { this.channel = channel; }

However, this breaks the first unit test, and you have to go back and fix the first unit test in order to make the test suite compile:

[Fact] public void SutIsController() { var channelDummy = new Mock<ICommandChannel>(); var sut = new BasketController(channelDummy.Object); Assert.IsAssignableFrom<IHttpController>(sut); }

In this example only a single unit test broke, but it gets progressively worse as you go along.

Satisfied with your implementation so far, you now decide to implement a feature where the client of the service can read the basket. This is supported by the HTTP GET method, so you write this unit test to drive the feature into existence:

[Fact] public void GetReturnsCorrectResult() { // Arrange var readerStub = new Mock<IBasketReader>(); var expected = new BasketModel(); readerStub.Setup(r => r.GetBasket()).Returns(expected); var channelDummy = new Mock<ICommandChannel>().Object; var sut = new BasketController(channelDummy, readerStub.Object); // Act var response = sut.Get(); var actual = response.Content.ReadAsAsync<BasketModel>().Result; // Assert Assert.Equal(expected, actual); }

This test introduces yet another dependency into the SUT, forcing you to change the BasketController constructor to this:

private ICommandChannel channel; private IBasketReader reader; public BasketController(ICommandChannel channel, IBasketReader reader) { this.channel = channel; this.reader = reader; }

Alas, this breaks both previous unit tests and you have to revisit them and fix them before you can proceed.

In this simple example, fixing a couple of unit tests in order to introduce a new dependency doesn't sound like much, but if you already have hundreds of tests, the prospect of breaking dozens of tests each time you wish to refactor by moving dependencies around can seriously hamper your productivity.

Refactoring notes #

The problem is that the tests are too tightly coupled to the mechanics of how the SUT is constructed. The irony is that although you somehow need to create instances of the SUT, you shouldn't really care about how it happens.

If you closely examine the tests in the motivating example, you will notice that the SUT is created in the Arrange phase of the test. This phase of the test is also called the Fixture Setup phase; it's where you put all the initialization code which is required before you can interact with the SUT. To be brutally honest, the code that goes into the Arrange phase is just a necessary evil. You should care only about the Act and Assert phases - after all, these tests don't test the constructors. In other words, what happens in the Arrange phase is mostly incidental, so it's unfortunate if that part of a test is holding you back from refactoring. You need a way to decouple the tests from the constructor signature, while still being able to manipulate the injected dynamic mock objects.

There are various ways to achieve that goal. A common approach is to declare the SUT and its dependencies as class fields and compose them all as part of a test class' Implicit Setup . This can be an easy way to address the issue, but carries with it all the disadvantages of the Implicit Setup pattern. Additionally, it can lead to an explosion of fields and low cohesion of the test class itself.

Another approach is to build the SUT with a helper method. However, if the SUT has more than one dependency, you may need to create a lot of overloads of such helper methods, in order to manipulate only the dynamic mocks you may care about in a given test case. This tends to lead towards the Object Mother (anti-)pattern.

A good alternative is an Auto-mocking Container to decouple the tests from the constructor signature of the SUT.

Example: Castle Windsor as an Auto-mocking Container #

In this example you repurpose Castle Windsor as an Auto-mocking Container. Castle Windsor is one among many DI Containers for .NET with a pretty good extensibility model. This can be used to turn the standard WindsorContainer into an Auto-mocking Container. In this case you will combine it with Moq in order to automatically create dynamic mocks every time you need an instance of an interface.

It only takes two small classes to make this happen. The first class is a so-called SubDependencyResolver that translates requests for an interface into a request for a mock of that interface:

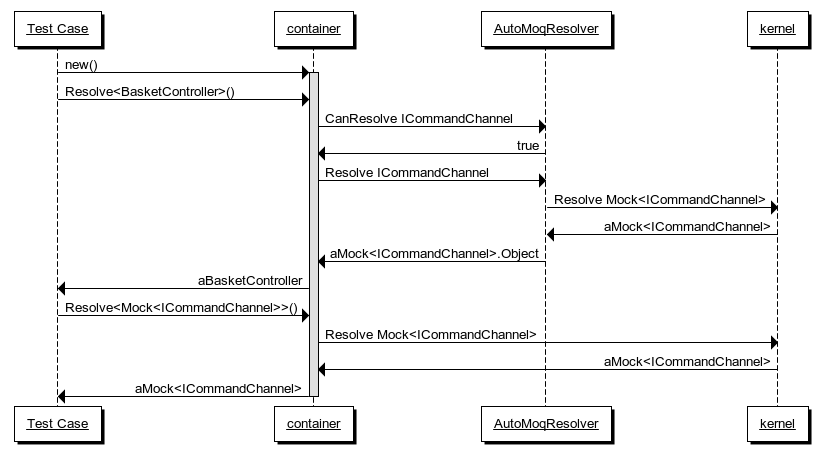

public class AutoMoqResolver : ISubDependencyResolver { private readonly IKernel kernel; public AutoMoqResolver(IKernel kernel) { this.kernel = kernel; } public bool CanResolve( CreationContext context, ISubDependencyResolver contextHandlerResolver, ComponentModel model, DependencyModel dependency) { return dependency.TargetType.IsInterface; } public object Resolve( CreationContext context, ISubDependencyResolver contextHandlerResolver, ComponentModel model, DependencyModel dependency) { var mockType = typeof(Mock<>).MakeGenericType(dependency.TargetType); return ((Mock)this.kernel.Resolve(mockType)).Object; } }

The ISubDependencyResolver interface is a Castle Windsor extensibility point. It follows the Tester-Doer pattern, which means that the WindsorContainer will first call the CanResolve method, and subsequently only call the Resolve method if the return value from CanResolve was true.

In this implementation you return true if and only if the requested dependency is an interface. When this is the case, you construct a generic type of Moq's Mock<T> class. For example, in the code above, if dependency.TargetType is the interface ICommandChannel, the mockType variable becomes the type Mock<ICommandChannel>.

The next line of code asks the kernel to resolve that type (e.g. Mock<ICommandChannel>). The resolved instance is cast to Mock in order to access and return the value of its Object property. If you ask the kernel for an instance of Mock<ICommandChannel>, it'll return an instance of that type, and its Object property will then be an instance of ICommandChannel. This is the dynamic mock object you need in order to compose a SUT with automatic Test Doubles.

The other class wires everything together:

public class ShopFixture : IWindsorInstaller { public void Install( IWindsorContainer container, IConfigurationStore store) { container.Kernel.Resolver.AddSubResolver( new AutoMoqResolver( container.Kernel)); container.Register(Component .For(typeof(Mock<>))); container.Register(Classes .FromAssemblyContaining<Shop.MvcApplication>() .Pick() .WithServiceSelf() .LifestyleTransient()); } }

This is an IWindsorInstaller, which is simply a way of packaging Castle Windsor configuration together in a class. In the first line you add the AutoMoqResolver. In the next line you register the open generic type Mock<>. This means that the WindsorContainer knows about any generic variation of Mock<T> you might want to create. Recall that AutoMockResolver asks the kernel to resolve an instance of Mock<T> (e.g. Mock<ICommandChannel>). This registration makes this possible.

Finally, the ShopFixture scans through all public types in the SUT assembly and registers their concrete types. This is all it takes to turn Castle Windsor into an Auto-mocking Container.

Once you've done that, you can start TDD'ing, and you should rarely (if ever) have to go back to the ShopFixture to tweak anything.

The first test you write is equivalent to the first test in the previous motivating example:

[Fact] public void SutIsController() { var container = new WindsorContainer().Install(new ShopFixture()); var sut = container.Resolve<BasketController>(); Assert.IsAssignableFrom<IHttpController>(sut); }

First you create the container and install the ShopFixture. This is going to be the first line of code in all of your tests.

Next, you ask the container to resolve an instance of BasketController. At this point there's only a default constructor, so Auto-mocking hasn't even kicked in yet, but you get an instance of the SUT against which you can make your assertion.

Now it's time to write the next test, equivalent to the second test in the motivating example:

[Fact] public void PostSendsCorrectEvent() { var container = new WindsorContainer().Install(new ShopFixture()); var sut = container.Resolve<BasketController>(); var item = new BasketItemModel { ProductId = 1234, Quantity = 3 }; sut.Post(item); var expected = item.AddToBasket(); container .Resolve<Mock<ICommandChannel>>() .Verify(c => c.Send(expected)); }

Here an interesting thing happens. Notice that the first two lines of code are the same as in the previous test. You don't need to define the mock object before creating the SUT. In fact, you can exercise the SUT without ever referencing the mock.

In the last part of the test you need to verify that the SUT interacted with the mock as expected. At that time you can ask the container to resolve the mock and verify against it. This can be done in a single method call chain, so you don't even have to declare a variable for the mock.

This is possible because the ShopFixture registers all Mock<T> instances with the so-called Singleton lifestyle. The Singleton lifestyle shouldn't be confused with the Singleton design pattern. It means that every time you ask a container instance for an instance of a type, you will get back the same instance. In Castle Windsor, this is the default lifestyle, so this code:

container.Register(Component .For(typeof(Mock<>)));

is equivalent to this:

container.Register(Component .For(typeof(Mock<>)) .LifestyleSingleton());

When you implement the Post method on BasketController by injecting ICommandChannel into its constructor, the test is going to pass. This is because when you ask the container to resolve an instance of BasketController, it will need to first resolve an instance of ICommandChannel.

This is done by the AutoMoqResolver, which in turn asks the kernel for an instance of Mock<ICommandChannel>. The Object property is the dynamically generated instance of ICommandChannel, which is injected into the BasketController instance ultimately returned by the container.

When the test case subsequently asks the container for an instance of Mock<ICommandChannel> the same instance is reused because it's configured with the Singleton lifestyle.

More importantly, while the second test prompted you to change the constructor signature of BasketController, this change didn't break the existing test.

You can now write the third test, equivalent to the third test in the motivating example:

[Fact] public void GetReturnsCorrectResult() { var container = new WindsorContainer().Install(new ShopFixture()); var sut = container.Resolve<BasketController>(); var expected = new BasketModel(); container.Resolve<Mock<IBasketReader>>() .Setup(r => r.GetBasket()) .Returns(expected); var response = sut.Get(); var actual = response.Content.ReadAsAsync<BasketModel>().Result; Assert.Equal(expected, actual); }

Once more you change the constructor of BasketController, this time to inject an IBasketReader into it, but none of the existing tests break.

This example demonstrated how to repurpose Castle Windsor as an Auto-mocking Container. It's important to realize that this is still a pure unit testing concern. It doesn't require you to use Castle Windsor in your production code.

Other DI Containers can be repurposed as Auto-mocking Containers as well. One option is Autofac, and while not strictly a DI Container, another option is AutoFixture.

This article first appeared in the Open Source Journal 2012 issue 4. It is reprinted here with kind permission.

Test trivial code

Even if code is trivial you should still test it.

A few days ago, Robert C. Martin posted a blog post on The Pragmatics of TDD, where he explains that he doesn't test-drive everything. Some of the exceptions he give, such as not test-driving GUI code and true one-shot code, make sense to me, but there are two exceptions I think are inconsistent.

Robert C. Martin states that he doesn't test-drive

- getters and setters

- one-line functions

- functions that are obviously trivial

There are several problems with this exception that I'd like to point out:

- It confuses cause and effect

- Trivial code may not stay trivial

- It's horrible advice for novices

Causality #

The whole point of Test-Driven Development is that the tests drive the implementation. The test is the cause and the implementation is the effect. If you accept this premise, then how on Earth can you decide not to write a test because the implementation is going to be trivial? You don't know that yet. It's logically impossible.

Robert C. Martin himself proposed the Transformation Priority Premise (TPP), and one of the points here is that as you start out test-driving new code, you should strive to do so in small, formalized steps. The first step is extremely likely to leave you with a 'trivial' implementation, such as returning a constant.

With the TPP, the only difference between trivial and non-trivial implementation code is how far into the TDD process you've come. So if 'trivial' is all you need, the only proper course is to write that single test that demonstrates that the trivial behavior works as expected. Then, according to the TPP, you'd be done.

Encapsulation #

Robert C. Martin's exception about getters and setters is particularly confounding. If you consider a getter/setter (or .NET property) trivial, why even have it? Why not expose a public class field instead?

There are good reasons why you shouldn't expose public class fields, and they are all releated to encapsulation. Data should be exposed via getters and setters because it gives you the option of changing the implementation in the future.

What do we call the process of changing the implementation code without changing the behavior?

This is called refactoring. How do we know that when we change the implementation code, we don't change the behavior?

As Martin Fowler states in Refactoring, you must have a good test suite in place as a safety net, because otherwise you don't know if you broke something.

Successful code lives a long time and evolves. What started out being trivial may not remain trivial, and you can't predict which trivial members will remain trivial years in the future. It's important to make sure that the trivial behavior remains correct when you start to add more complexity. A regression suite addresses this problem, but only if you actually test the trivial features.

Robert C. Martin argues that the getters and setters are indirectly tested by other test cases, but while that may be true when you introduce the member, it may not stay true. Months later, those tests may be gone, leaving the member uncovered by tests.

You can look at it like this: with TDD you may be applying the TPP, but for trivial members, the time span between the first and second transformation may be measured in months instead of minutes.

Learning #

It's fine to be pragmatic, but I think that this 'rule' that you don't have to test-drive 'trivial' code is horrible advice for novices. If you give someone learning TDD a 'way out', they will take it every time things become difficult. If you provide a 'way out', at least make the condition explicit and measurable.

A fluffy condition that "you may be able to predict that the implementation will be trivial" isn't at all measurable. It's exactly this way of thinking that TDD attempts to address: you may think that you already know how the implementation is going to look, but letting tests drive the implementation, it often turns out that you'll be suprised. What you originally thought would work doesn't.

Addressing the root cause #

Am I insisting that you should test-drive all getters and setters? Yes, indeed I am.

But, you may say, it takes too much time? Ironically, Robert C. Martin has much to say on exactly that subject:

The only way to go fast, is to go well

Even so, let's see what it would be like to apply the TPP to a property (Java programmers can keep on reading. A C# property is just syntactic suger for a getter and setter).

Let's say that I have a DateViewModel class and I'd like it to have a Year property of the int type. The first test is this:

[Fact] public void GetYearReturnsAssignedValue() { var sut = new DateViewModel(); sut.Year = 2013; Assert.Equal(2013, sut.Year); }

However, applying the Devil's Advocate technique, the correct implementation is this:

public int Year { get { return 2013; } set { } }

That's just by the TPP book, so I have to write another test:

[Fact] public void GetYearReturnsAssignedValue2() { var sut = new DateViewModel(); sut.Year = 2010; Assert.Equal(2010, sut.Year); }

Together, these two tests prompt me to correctly implement the property:

public int Year { get; set; }

While those two tests could be refactored into a single Parameterized Test, that's still a lot of work. Not only do you need to write two test cases for a single property, but you'd have to do exactly the same for every other property!

Exactly the same, you say? And what are you?

Ah, you're a programmer. What do programmers do when they have to do exactly the same over and over again?

Well, if you make up inconsistent rules that enable you to skip out of doing things that hurt, then that's the wrong answer. If it hurts, do it more often.

Programmers automate repeated tasks. You can do that when testing properties too. Here's how I've done that, using AutoFixture:

[Theory, AutoWebData] public void YearIsWritable(WritablePropertyAssertion a) { a.Verify(Reflect<DateViewModel>.GetProperty<int>(sut => sut.Year)); }

This is a declarative way of checking exactly the same behavior as the previous two tests, but in a single line of code.

Root cause analysis is in order here. It seems as if the cost/benefit ratio of test-driving getters and setters is too high. However, I think that when Robert C. Martin stops there, it's because he considers the cost fixed, and the benefit is then too low. However, while the benefit may seem low, the cost doesn't have to be fixed. Lower the cost, and the cost/benefit ratio improves. This is why you should also test-drive getters and setters.

Update 2014.01.07: As a follow-up to this article, Jon Galloway interviewed me about this, and other subject, for a Herding Code podcast.

Update, 2018.11.12: A new article reflects on this one, and gives a more nuanced picture of my current thinking.

Comments

Here is a concrete, pragmatic, example where this post really helped in finding a solution to a dilemma on whether (or not) we should test a (trivial) overriden ToString method's output. Mark Seemann explained why in this case (while the code is trivial) we should not test that particular method. Even though it is a very concrete example, I believe it will help the reader on making decisions about when, and whether it's worth (or not), to test trivial code.

Code readability hypotheses

This post proposes a scientific experiment about code readability

Once in a while someone tries to drag me into one of many so-called 'religious' debates over code readability:

- Tabs versus spaces?

- Where should the curly braces go?

- Should class members be prefixed (e.g. with an underscore)?

- Is the

thisC# keyword redundant? - etc.

In most cases, the argument revolves around what is most readable.

Let's look at the C# keyword this as an example. Many programmers feel that it's redundant because they can omit it without changing the program. The compiler doesn't care. However, as Martin Fowler wrote in Refactoring: "Any fool can write code that a computer can understand. Good programmers write code that humans can understand." Code is read much more than written, so I don't buy the argument about redundancy.

There are lots of circumstances when code is read. Often, programmers read code from inside their IDE. This has been used as an argument against Hungarian notation. However, at other times, you may be reading code as part of a review process - e.g. on GitHub or CodePlex. Or you may be reading code on a blog post, or in a book.

Often I feel that the this keyword helps me because it provides information about the scope of a variable. However, I also preach that code should consist of small classes with small methods, and if you follow that principle, variable scoping should be easily visible on a single screen.

Another argument against using the this keyword is that it's simply noise and that it makes it harder to read the program, simply because there's more text to read. Such a statement is impossible to refute with logic, because it depends on the person reading the code.

Ultimately, the readability of code depends on circumstances and is highly subjective. For that reason, we can't arrive at a conclusion to any of those 'religious' debates by force of logic. However, what we could do, on the other hand, is to perform a set of scientific experiments to figure out what is most readable.

A science experiment idea for future computer scientists #

Here's an idea for a computer science experiment:

- Pick a 'religious' programming debate (e.g. whether or not the

thiskeyword enhances or reduces readability). - Form a hypothesis (e.g. predict that the

thiskeyword enhances readability). - Prepare a set of simple code listings, each with two alternatives (with and without

this). - Randomly select two groubs of test subjects.

- Ask each group to explain to you what the code does (what is the result of calling a method, etc.). One group gets one alternative set, and the other group gets the other set.

- Measure how quickly members of each group arrives at a correct conclusion.

- Compare results against original hypothesis.

Code readability hypotheses by Mark Seemann is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

Comments

Totally agreed.

I believe that these 'religious' debates is the result of overreliance to some popular Productivity Tools. If these tools never existed those debates would appear less often.

Where possible, I use this and base.

From a code reader's perspective, I also prefer this since I can immediately understand whether a member of a class is either a static member or an instance member. After all, it is possible to prefix a static member with _ but not with this.

The import thing that emerges from this interesting post is that readabiliy is a key feature of code.

I'm a fun of this concept: code is meant to be read. A person able to program is not a programmer, like a person able to write is not a writer.

The good compromise is common sense.

The scenitifical experiment proposed could give use misleading informations, since the human factor is a problematic variable to put into the equation (not to mention Heisenberg); but I would be curious to see results.

Coming back to the this keyword, my personal opinion is that it can be omitted, if your naming convention supplies a readable alternative (like the _ underscore prefix before private instance members).

I also agree that code should be readable.

However, this being said, the proposed method for testing the hypothesis does not hold from a statistical point of view.

Just to mentionen a few of the issues:

- The two groups could have different leves of experience which would influence their 'ability' to read and understand the code

- Demografics such as age, gender, native language, education, ..., would also influence the result

- The individual members of the group could be biased towards one or the other, in the used example for or against the use of the this keyword

- Simply to compile large enough groups to ensure a low statistics error would be an issue

The word 'religious' is mentioned and this is the main problem. Different from science that is based on deduction, religion is based on beliefe (or faith) and precisely because of this cannot be tested or verified.

Karsten, I think you're reading practical issues into my proposal. Would you agree that all but the last of your reservations could be addressed if one were to pick large enough groups of test subjects, without selection bias?

That's what I meant when I wrote "Randomly select two groups of test subjects".

If one were able to pick large enough groups of people, one should be able to control for variables such as demographics, experience, initial biases, and so on.

Your last reservation, obviously, is fundamentally different. How many people would one need in order to be able to control for such variables in a statistically sound fashion? Probably thousands, if not tens of thousands, of programmers, including professional developers. This precludes the use of normal test subject populations of first-year students.

Clearly, compiling such a group of test subjects would be a formidable undertaking. It'd be expensive.

My original argument, however, was that I consider it possible to scientifically examine contentious topics of programming. I didn't claim that it was realistic that anyone would fund such research.

To be clear, however, the main point of the entire article is that we can't reach any conclusions about these controversial issues by arguing about them. If we wish to settle them, we'll have to invest in scientific experiments. I have no illusions that there's any desire to invest the necessary funds and work into answering these questions, but I would love to be proven wrong.

There is a huge problem in the way that we evaluate software quality. Karsten, is naming many of the reasons that make it difficult. But given that it is difficult, The only rational way to solve it without relying as heavily credentials, personality and repetition. Is to establish guidelines and have multiple opionins/measurements of code samples.

I think we overvalue experience in evaluating code. And in the contrary, there are real issues with expert bias, particularly of older programmers who have good credentials but are more financially and emotionally invested in a particular technology. In general, it is much more difficult to write good code, than to read it. Therefore, most programmers can read, understand and appreciate good code. While they may not have been able to write from scratch themselves. The only exception would be for true neophytes (which there may be ways to exclude). We also need to be leary about software qualities that are hard to grasp and evaluate. Unexplainable or unclear instinct can lead to bad outcomes.

There is real oportunity here to more scientifically quantify aspects of code quality. I wish more people devoted time to it.

Outside-In TDD versus DDD

Is there a conflict between Outside-In TDD and DDD? I don't think so.

A reader of my book recently asked me a question:

"you are a DDD and TDD fan and at the same time you like to design your User Interfaces first. I have been reading about DDD and TDD for some time now and your approach confuses me, TDD is about writing tests first to lead the design, DDD is focusing on the domain yet you start with the UI."

In my opinion there's no conflict between Outside-In TDD and DDD, but I must admit that I was a bit surprised by the question. It never occurred to me that there's an apparent conflict between these two approaches, but now that I was asked the question, I understand why one would think so. In other words, I think it's a good question that warrants a proper answer.

Before discussing the synthesis of Outside-In TDD and DDD I think we need to examine each concept individually.

DDD #

As far as I can tell, Domain-Driven Design is a horribly misunderstood book. By corollary, so is the DDD concept itself. The problem with the book is that it provides value and guidance along two axes:

- Patterns and other coding advice

- Principles for analysis and modeling

Don't let the fact that all these patterns are described in a book called Domain-Driven Design trick you into thinking that they are intrinsically bound to DDD. Using the patterns don't make your code Domain-Driven, and you can do DDD without them. Obviously, you can also combine them.

This provides a partial answer to the original question. Outside-In TDD doesn't conflict with the patterns described in Domain-Driven Design, just as it doesn't conflict with most other design patterns.

That still leaves the 'true' DDD: the principles for analyzing and modeling the subject matter for a piece of software. If that is a design technique, and Outside-In TDD is also a design technique, isn't there a conflict?

Outside-In TDD #

Outside-In TDD, as I describe it in my Pluralsight course, isn't a design technique. TDD isn't a design technique. Granted, TDD provides fast feedback about the design you are implementing, but it's not a blind design technique.

Outside-In TDD and DDD #

Once you realize that a major reason that Outside-In TDD and DDD seems to be at odds, is because of the false premise that TDD is a design technique, you should also realize that there isn't, after all, any conflict. There's no reason that you can't do both, but it doesn't mean you always should.

- You can do Outside-In TDD without DDD. If you are building a CRUD application, DDD is probably going to be overkill. If so, skip it.

- You can do DDD without Outside-In TDD. If you are being paid to build or extract a true Domain Model, it makes sense to do so decoupled from any sort of application boundaries.

- You can combine Outside-In TDD with DDD, but I think this will often make best sense as an iterative approach. First you build the application. Then you realize that the business logic within the application is so complex that you'll need to extract a proper Domain Model in order to keep it maintainable.

In my Pluralsight course, I also discuss the Test Pyramid. While it makes sense to begin development at the boundary (e.g. UI) of an application, you shouldn't stay at the boundary. Most tests should still be unit tests. Once you reach the phase where you realize that you'll need to evolve a proper Domain Model, you should do that with unit tests, not boundary tests. Domain Models should be implemented decoupled from all boundaries (UI, I/O and persistence), so you can only directly test a Domain Model with unit tests.

In the end, it's all a question of perspective. Outside-In TDD states that you should begin your TDD process at the boundary. In the beginning, it will focus on the externally visible behavior of the system, but as development progresses, other parts of the system must be dealt with. This is where DDD can be valuable. The lack of conflict eventually stems from the fact that Outside-In TDD and DDD operate on different levels of application architecture, with little overlap.

In my experience, a lot of applications can be written with Outside-In TDD without a Domain Model ever having to evolve - and still be maintainable. These applications may still employ the 'Supple Design Patterns', but that doesn't mean that they are Domain-Driven.

Comments

Thank for this insightful post. It inspired me to write a post about the two sides of DDD.

PS: IMO, commenting via pull-request is too burdensome. Have you considered Disqus?

Lev, thank you for your comment. While I've considered Disqus and other alternatives, I don't want to go in that direction. Free services have a tendendcy to not remain free forever - Google Reader being a current case in point.

Moving the blog to Jekyll

ploeh blog is sorta moving

For more than four years ploeh blog has been driven by dasBlog, since I originally had to move away from my original MSDN blog. At the time, dasBlog seemed like a good choice for a variety of reasons, but not too long after, development seemed to stop.

It's my hope that, as a reader, you haven't been too inconvenienced about that choice of blogging engine, but as the owner and author, I've grown increasingly frustrated with dasBlog. Yesterday, ploeh blog moved to a new platform and a new host.

What's new? #

The new platform for ploeh blog is Jekyll-Bootstrap hosted on GitHub pages. If you don't know what Jekyll-Bootstrap is, it's a parsing engine that creates a complete static web site from templates and data. This means that when you read this on the internet, you are reading a static HTML page served directly from a file. There's no application server involved.

Since ploeh blog is now a static web site, I had to make a few shortcuts here and there. One example is that I can't have any forms on the web site, so I can't have a contact me form - but I didn't have that before either, so that's not really a problem. There are still plenty of ways in which you can contact me.

Another example is that the blog can't have a server-driven comment engine. As an alternative, Jekyll provides several options for including a third-party commenting service, such as Disqus, Livefyre, IntenseDebate, etc. I could have done that too, but have chosen to try another alternative.

There are several reasons why I prefer to avoid a third-party solution. First of all, in case you haven't noticed, I'm into this whole blogging thing for the long haul. I've been steadily blogging since January 2006, and have no plans to stop. Somehow, I expect to keep blogging for a longer period than I expect the average third-party content provider to last - or to keep their service free.

Second, I think it's more proper to keep the comments with ploeh blog. These comments were originally submitted by their authors to ploeh blog, which implies that they trusted me to treat them with respect. If I somehow were to move all those comments to a third party, what would become of the copyright?

Third, while it wasn't entirely trivial to merge the comments into each post, it looked like the simplest solution, compared to have to somehow migrate comments for some 200+ posts to a third party using an unknown (to me) API.

What this all means is that I've decided to simply keep the comments as part of the body of the post. Comments, too, is static content. This also means that comments are included in syndication feeds - a side effect that I'm not entirely happy about, but for which I don't yet have a good solution.

So, if comments are all static, does it mean that I no longer accept comments? No, I still accept comments. Just send me a pull request. Snarky, perhaps, but the advantage of that is that if you want, you'll have a lot more flexibility if you want to comment: you could include code, images, tables, lists, etc. The only checkpoint you'll have to get past is me :)

Actually, you are welcome to send me pull requests for other enchancements as well, if you'd like. Did I spell a word incorrectly? Send me a pull request. Is a link broken? Send me a pull request. Do you know way more about web site design than I do and want to help? Send me a pull request :) Seriously, as you may have noticed, ploeh blog is currently using the default Twitter Bootstrap design. That's not particularly interesting to look at, but I hope that the most important part of the blog is the content, so I didn't use much energy on changing the look - it probably wouldn't have been to the better anyway.

Since the content is the most important part of the blog, I've also gone to some lentgth to ensure that old permalinks to posts still work. If you encounter a link that no longer works, please let me know (or send me a pull request).

Finally, as all RSS subscribers have probably noticed by now, switching the blog has caused some RSS hiccups. While the old feed address still works, the permalink URL scheme has changed, because I didn't think it made sense to have static files and URLs ending with .aspx.

What was wrong with dasBlog? #

Originally, I chose dasBlog as a blogging engine because it had some attractive features. However, the main problem with it is that it's no longer being maintained. There seems to be no roadmap for it.

Second, the commenting feature didn't work well. Many readers had trouble submitting comments, particularly if they wanted to include links or other HTML formatting. I also got a lot of comment spam.

Finally, the authoring experience slowly degraded. The built-in editor only worked in Firefox, and while I don't mind having Firefox installed, it was a cause of concern that I could only edit with one out of three installed browsers. What if it also stopped working in Firefox?

It was definitely time to move on, but whereto?

Why Jekyll? #

Before I decided to go with Jekyll, I looked at various options for blogging sofware or services, including WordPress.com, Blogger, FunnelWeb, Orchard, and others. However, none of them could meet my requirements:

- Simplicity. Everything that required a relational database to host a blog was immediately dismissed. This is 2013. A RDBMS for a single user blog site? Seriously?

- Easy hosting. Requiring a RDBMS significantly constrains my deployment options. It also tends to make hosting much more expensive. Since January 2009 I've been hosting ploeh blog on my own server in my home, but I've become increasingly annoyed at having to operate my own server. This is, after all, 2013.

- Backwards compatible. The new blog should be able to handle the old blog's permalinks. Redirects were OK, but I couldn't just leave hundreds of external links to ploeh blog with a 404. That pretty much ruled out all hosted services.

- Forward compatible. This is the second time I change blog platform, and it's not going to be the last. I need a solution that enables me to move forward, taking all the existing content with me to a new service or platform.

I seriously toyed with writing my own blogging engine to meet all those requirements, but soon realized that Jekyll was a pretty good match. It's not perfect, but good enough for now.

Comments

While I like the move of the blog post to GitHub, the overhead of creating comments here is just too high. I like having some level of entry barrier to keep the quality up but this is more to the point of completely detracting additional useful information from being posted in comments.

An option that comes to mind could be possibly using the Issue tracking system in GitHub for comments or something that gives access to the GitHub markdown features like the pages themselves.

AutoFixture 3

Announcing the general release of AutoFixture 3.

AutoFixture 3 has been under way in a long time, but after about of a month of limited beta/CTP/whatever trial, I've decided to release it as the 'official' current version of AutoFixture. Since AutoFixture uses Semantic Versioning, the shift from 2.16.2 to 3.0.0 (actually, 3.0.1) signifies breaking changes. While we've made an effort to make the impact of these breaking changes as light as possible, it's worth noting that it's probably not a good idea upgrading to AutoFixture 3 five minutes before you are heading out of the door for the weekend.

Read more about what's new and what has changed in the release notes.

Thank you to everyone who helped make this happen. There have been a lot of people contributing, providing feedback, asking intelligent questions, etc. but I particularly want to thank Nikos Baxevanis for all the work he's been putting into AutoFixture. Conversely, as is usual in such circumstances, all mistakes are my responsibility.

What's new? #

When you read the release notes, you may find the amount of new features is quite unimpressive. This is because we've been continually releasing new features under the major version number of 2, in a sort of Continuous Delivery process. Because of the way Semantic Versioning works, breaking changes must be signaled by increasing the major version number, so while we could release new features as they became available, I thought it better to bundle up breaking changes into a bigger release; if not, we'd be looking at AutoFixture 7 or 8 now... And as I'm writing this, I notice that my installation of Chrome is on major version 25, so maybe it's just something I need to get over.

Personal release notes #

One thing that the release notes don't explicitly mention, but I'd like to talk about a little is that AutoFixture 3 is running on an extensively rebuilt kernel. One of the visions I had for AutoFixture 3 was that the kernel structure should be immutable, and it should be as easy to take away functionality than it is to add custom functionality. Taking away functionality was really hard (or perhaps impossible) in AutoFixture 2, and that put a constraint on what you could do with AutoFixture. It also put a constraint on how opinionated its defaults could be.

The AutoFixture 3 kernel makes it possible to take away functionality, as well as add new functionality. At the moment, you have to understand the underlying kernel to figure out how to do that, but in the future I plan to surface an API for that as well.

In any case, I find it interesting that using real SOLID principles, I was able to develop the new kernel in parallel with the version 2 kernel. Partly because I was very conscious of not introducing breaking changes, but also because I follow the Open/Closed Principle, I rarely had to touch existing code, but could build the new parts of the kernel in parallel. Even more interestingly, I think, is the fact that once that work was done, replacing the kernel turned out to be a point release. This happened late November 2012 - more than three months ago. If you've been using AutoFixture 2.14.1 or a more recent version, you've already been using the AutoFixture 3 kernel for some time.

The reason I find this interesting is that sometimes casual readers of my blog express skepticism over whether the principles I talk about can be applied in 'realistic' settings. According to Ohloh, AutoFixture has a total of 197,935 lines of code, and I consider that a fair sized code base. I practice what I preach. QED.

String Calculator kata with Autofixture exercise 8

This is the eighth post in a series of posts about the String Calculator kata done with AutoFixture.

This screencast implements the requirement of the kata's exercise 8 and 9. Although the kata has nine steps, it turned out that I slightly misinterpreted the requirements of exercise 8 and ended up implementing the requirements of exercise 9 as well as those of exercise 8 - or perhaps I was just gold plating.

If you liked this screencast, you may also like my Pluralsight course Outside-In Test-Driven Development.

String Calculator kata with Autofixture exercise 7

This is the seventh post in a series of posts about the String Calculator kata done with AutoFixture.

This screencast implements the requirement of the kata's exercise 7.

If you liked this screencast, you may also like my Pluralsight course Outside-In Test-Driven Development.

String Calculator kata with Autofixture exercise 6

This is the sixth post in a series of posts about the String Calculator kata done with AutoFixture.

This screencast implements the requirement of the kata's exercise 6.

If you liked this screencast, you may also like my Pluralsight course Outside-In Test-Driven Development.

String Calculator kata with Autofixture exercise 5

This is the fifth post in a series of posts about the String Calculator kata done with AutoFixture.

This screencast implements the requirement of the kata's exercise 5.

If you liked this screencast, you may also like my Pluralsight course Outside-In Test-Driven Development.

Comments

It seems you assume that the int generator always returns non-negative numbers.

Is this true and by design? why?

Thanks

In AutoFixture 3, numbers are random.

In AutoFixture 2.2+, all numbers are generated by a strictly monotonically increasing sequence.

In AutoFixture prior to 2.2, numbers were also generated as a rising sequence, but one sequence per number type.

Common for all is that they are 'small, positive integers'.

Comments

First of all, thank you for a very informative article.

I'd like to call out another example of an Auto Mocking Container that I've picked up recently and enjoyed working with. It's built into Machine.Fakes, an MSpec extension library that abstracts the details of different mocking libraries behind an expressive API.

I rewrote the third test with MSpec and Machine.Fakes to demonstrate its usage:

There are a couple of interesting points to highlight here. The

WithSubject<T>class hides the details of composing the SUT, which is then exposed through theSubjectproperty. It makes sure that any dependencies are automatically fulfilled with Test Doubles, created by delegating to a mocking library of choice. Those singleton instances can then be obtained from the test using the inheritedThe<T>()to setup stubs or make assertions.What I like about Machine.Fakes is that it gives me the advantages of using an Auto Mocking Container, while keeping the details of how the SUT is composed out of the test, thus allowing it to stay focused on the behavior to verify.