ploeh blog danish software design

Why I'm migrating from MSTest to xUnit.net

About a month ago I decided to migrate from MSTest to xUnit.net, and while I am still in the process, I haven't regretted it yet, and I don't expect to. AutoFixture has already moved over, and I'm slowly migrating all the sample code for my book.

Recently I was asked why, which prompted me to write this post.

I'm not moving away from MSTest for one single reason. It's rather like lots of small reasons.

When I originally started out with TDD, I used nUnit - it was more or less the only unit testing framework available for .NET at the time. When MSTest came, the change was natural, since I worked for Microsoft at the time. This is not the case anymore, but it still took me most of a year to finally abandon MSTest.

There was one thing that really made me cling to MSTest, and that was the IDE integration, but over time, I started to realize that this was the only reason, and even that was getting flaky.

When I started to think about all the things that left me dissatisfied, making the decision was easy:

- First of all, MSTest isn't extensible, but xUnit.net is. In xUnit.net, I can extend the Fact or Theory attributes (and I intent to), while in MSTest, I will have to play with the cards I've been dealt. I think I could live with all the other issues if I could just have this one, but no.

- MSTest has no support for parameterized test. xUnit.net does (via the Theory attribute).

- MSTest has no Assert.Throws, although I requested this feature a long time ago. Now Visual Studio 2010 is out, but Assert.Throws is still nowhere in sight.

- MSTest has no x64 support. Tests always run as x86. Usually it's no big deal, but sometimes it's a really big deal.

- In MSTest, to write unit tests, you must create a special Unit Test Project, and those are only available for C# and VB.net. Good luck trying to write unit tests in a more exotic .NET language (like F# on Visual Studio 2008). xUnit.net doesn't have this problem.

- MSTest uses Test Lists and .vsmdi files to maintain test lists. Why? I don't care, I just want to execute my tests, and the .vsmdi files are in the way. This is particularly bad when you use TFS, but I'm also moving away from TFS, so that wouldn't have continued to be that much of an issue. Still: try having more than one .sln file with unit tests in the same folder, and watch funny things happen because they need to share the same .vsmdi file.

- I suppose it's because of the .vsmdi files, but sometimes I get a Test run error if I delete a test and run the tests immediately after. That's a false positive, if anyone cares.

- MSTest gives special treatment to its own AssertionException, which gets nice formatting in the Test Results window. All other exceptions (like verification exceptions thrown by Moq or Rhino Mocks are rendered near-intelligible because MSTest thinks it's very important to report the fully qualified name of the exception before its message. Most of the time, you have to open the Test Details window to see the exception message.

- Last, but not least, I often get cryptic exception messages like this one: Column 'id_column, runid_column' is constrained to be unique. Value '8c84fa94-04c1-424b-9868-57a2d4851a1d, d7471c5e-522f-43d3-b2c5-8f5cab55af0e' is already present. This appears in a very annoying modal MessageBox, but clicking OK and retrying usually works, although sometimes it even takes two or three attempts before I can get past this error.

It not one big thing, it's just a lot of small, but very annoying things. After three iterations (VS2005, VS2008 and now VS2010) these issue have still to be addressed, and I got tired of waiting.

So far, I can only say that I have none of these problems with xUnit.net and the IDE integration provided by TestDriven.NET. It's just a much smoother experience with much less friction.

AutoFixture 1.1

AutoFixture 1.1 is now available on the CodePlex site! Compared to the Release Candidate, there are no changes.

The 1.1 release page has more details about this particular release, but essentially this is the RC promoted to release status.

Release 1.1 is an interim release that addresses a few issues that appeared since the release of version 1.0. Work continues on AutoFixture 2.0 in parallel.

Dependency Injection is Loose Coupling

It seems to me that I've lately encountered a particular mindset towards Dependency Injection (DI). People seem to think that it's only really good for replacing one data access implementation with another. Once you get to that point, you know that the following argument isn't far behind:

“That's all well and good, but we know for certain that we will never exchange [insert name of RDBMS here] with anything else in this application.”

Apart from the hubris of making such a bold statement about the future of any software endeavor, such a statement reveals the narrow view on DI that its only purpose is for replacing data access components - and perhaps for unit testing.

Those are relevant reasons for using DI, but they are only some of the reasons. Let's briefly revisit why we employ DI.

We use DI to enable loose coupling.

DI is only a means to an end. Even if you never intend to replace your database and even if you never want to write a single unit test, DI still offers benefits in form of a more maintainable code base. The loose coupling gives you better separation of concerns because it allows you to apply the Open/Closed Principle.

Example coming right up:

Imagine that we need to implement a PrécisViewModel class with a TopSellers property that returns an IEnumerable<string>. To implement this class, we have a data access component. Let's use the ubiquitous Repository pattern and define IProductRepository to see where that leads us:

public interface IProductRepository { IEnumerable<Product> SelectTopSellers(); }

We can now implement PrécisViewModel like this:

public class PrécisViewModel { private readonly IProductRepository repository; public PrécisViewModel(IProductRepository repository) { if (repository == null) { throw new ArgumentNullException("repository"); } this.repository = repository; } public IEnumerable<string> TopSellers { get { var topSellers = this.repository.SelectTopSellers(); return from p in topSellers select p.Name; } } }

Nothing fancy is going on here. It's just straight Constructor Injection at work.

Obviously, we can now implement and use a SQL Server-based repository:

var repository = new SqlProductRepository(); var vm = new PrécisViewModel(repository);

So what does all this loose coupling buy us? It doesn't seem to help us a lot.

The real benefit is not yet apparent, but it should become more obvious when we start adding requirements. Let's start with some caching. It turns out that the SelectTopSellers implementation is slow, so we would like to add some caching somewhere.

Where should we add this caching functionality? Without loose coupling, we would more or less be constrained to adding it to either PrécisViewModel or SqlProductRepository, but both have issues:

- First of all we would be violating the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) in both cases.

- If we implement caching in PrécisViewModel, other consumers of the SelectTopSellers would not benefit from it.

- If we implement caching in SqlProductRepository, it wouldn't be available for any other IProductRepository implementations.

Since the premise for this post is that we will never use any other database than SQL Server, implementing caching directly in SqlProductRepository sounds like the correct choice, but we would still be violating the SRP, and thus making our code more difficult to maintain.

A better solution is to introduce a caching Decorator like this one:

public class CachingProductRepository : IProductRepository { private readonly ICache cache; private readonly IProductRepository repository; public CachingProductRepository( IProductRepository repository, ICache cache) { if (repository == null) { throw new ArgumentNullException("repository"); } if (cache == null) { throw new ArgumentNullException("cache"); } this.cache = cache; this.repository = repository; } #region IProductRepository Members public IEnumerable<Product> SelectTopSellers() { return this.cache .Retrieve<IEnumerable<Product>>("topSellers", this.repository.SelectTopSellers); } #endregion }

For completeness sake is here the definition of ICache:

public interface ICache { T Retrieve<T>(string key, Func<T> readThrough); }

The point is that CachingProductRepository extends any IProductRepository we provide to it (including SqlProductRepository) without modifying it. Thus, we have satisfied both the OCP and the SRP.

Just to drive home the point, let us assume that we also wish to record execution times for various methods for purposes of SLA compliance. We can do this by introducing yet another Decorator:

public class PerformanceMeasuringProductRepository : IProductRepository { private readonly IProductRepository repository; private readonly IStopwatch stopwatch; public PerformanceMeasuringProductRepository( IProductRepository repository, IStopwatch stopwatch) { if (repository == null) { throw new ArgumentNullException("repository"); } if (stopwatch == null) { throw new ArgumentNullException("stopwatch"); } this.repository = repository; this.stopwatch = stopwatch; } #region IProductRepository Members public IEnumerable<Product> SelectTopSellers() { var timer = this.stopwatch .StartMeasuring("SelectTopSellers"); var topSellers = this.repository.SelectTopSellers(); timer.StopMeasuring(); return topSellers; } #endregion }

Once again, we modified neither SqlProductRepository nor CachingProductRepository to introduce this new feature. We can implement security and auditing features by following the same principle.

To me, this is what loose coupling (and DI) is all about. That we can also replace data access components and unit test using dynamic mocks are very fortunate side effects, but the loose coupling is valuable in itself because it enables us to write more maintainable code.

We don't even need a DI Container to wire up all these repositories (although it sure would could be helpful). Here's how we can do it with Pure DI:

IProductRepository repository = new PerformanceMeasuringProductRepository( new CachingProductRepository( new SqlProductRepository(), new Cache() ), new RealStopwatch() ); var vm = new PrécisViewModel(repository);

The next time someone on your team claims that you don't need DI because the choice of RDBMS is fixed, you can tell them that it's irrelevant. The choice is between DI and Spaghetti Code.

Comments

Btw, i never figured out if there is anything why service locator isn't anti pattern. :)

I'm not sure I understand your comment regarding Service Locator. It is an anti-pattern :)

No, seriously, I never expected the entire world to just accept my word as gospel, and there are many people who disagree on this point. Did you have something specific in mind?

For me the interesting thing about the talk was that apparently this "separation of concerns" thing had been an important enough discovery for him that it warranted the use of half the presentation time to explain, with the other half being spent talking about the dangers of multi-threading :-)

A little off-topic, but how'd you implement Cache to force evaluation if it gets passed a Func<IEnumerable<Something>>? Else it will just cache the query.

However, we could always specialize the implementation of the cache so that if T was IEnumerable, we'd invoke ToList() on it before caching the result.

Thanks Mark. Any books from you scheduled for this year or the next?

What if IProductRepository has 15 methods but only one method should be cached?

Or what if I don't need always the cache? So I have a ProductService that needs a IProductRepository. For 5 cases the ProducrtService would need the CachingProductRepository and for the rest the standard ProductRepository?

However, if you have this scenario, could it be that the interface violates the Interface Segregation Principle?

Mapping types with AutoFixture

In my previous posts I demonstrated interaction-based unit tests that verify that a pizza is correctly being added to a shopping basket. An alternative is a state-based test where we examine the contents of the shopping basket after exercising the SUT. Here's an initial attempt:

[TestMethod] public void AddWillAddToBasket() { // Fixture setup var fixture = new Fixture(); fixture.Register<IPizzaMap>( fixture.CreateAnonymous<PizzaMap>); var basket = fixture.Freeze<Basket>(); var pizza = fixture.CreateAnonymous<PizzaPresenter>(); var sut = fixture.CreateAnonymous<BasketPresenter>(); // Exercise system sut.Add(pizza); // Verify outcome Assert.IsTrue(basket.Pizze.Any(p => p.Name == pizza.Name), "Basket has added pizza."); // Teardown }

In this case the assertion examines the Pizze collection (you did know that the plural of pizza is pizze, right?) of the frozen Basket to verify that it contains the added pizza.

The tricky part is that the Pizze property is a collection of Pizza instances, and not PizzaPresenter instances. The injected IPizzaMap instance is responsible for mapping from PizzaPresenter to Pizza, but since we are rewriting this as a state-based test, I thought it would also be interesting to write the test without using Moq. Instead, we can use the real implementation of IPizzaMap, but this means that we must instruct AutoFixture to map from the abstract IPizzaMap to the concrete PizzaMap.

We see that happening in this line of code:

fixture.Register<IPizzaMap>( fixture.CreateAnonymous<PizzaMap>);

Notice the method group syntax: we pass in a delegate to the CreateAnonymous method, which means that every time the fixture is asked to create an IPizzaMap instance, it invokes CreateAnonymous<PIzzaMap>() and uses the result.

This is, obviously, a general-purpose way in which we can map compatible types, so we can write an extension method like this one:

public static void Register<TAbstract, TConcrete>( this Fixture fixture) where TConcrete : TAbstract { fixture.Register<TAbstract>(() => fixture.CreateAnonymous<TConcrete>()); }

(I'm slightly undecided on the name of this method. Map might be a better name, but I just like the equivalence to some common DI Containers and their Register methods.) Armed with this Register overload, we can now rewrite the previous Register statement like this:

fixture.Register<IPizzaMap, PizzaMap>();

It's the same amount of code lines, but I find it slightly more succinct and communicative.

The real point of this blog post, however, is that you can map abstract types to concrete types, and that you can always write extension methods to encapsulate your own AutoFixture idioms.

Comments

AutoFixture 1.1 RC1

AutoFixture 1.1 Release Candidate 1 is now available on the CodePlex site.

Users are encouraged to evaluate this RC and submit feedback. If no bugs or issues are reported within the next week, we will promote RC1 to version 1.1.

The release page has more details about this particular release.

Freezing mocks

My previous post about AutoFixture's Freeze functionality included this little piece of code that I didn't discuss:

var mapMock = new Mock<IPizzaMap>(); fixture.Register(mapMock.Object);

In case you were wondering, this is Moq interacting with AutoFixture. Here we create a new Test Double and register it with the fixture. This is very similar to AutoFixture's built-in Freeze functionality, with the difference that we register an IPizzaMap instance, which isn't the same as the Mock<IPizzaMap> instance.

It would be nice if we could simply freeze a Test Double emitted by Moq, but unfortunately we can't directly use the Freeze method, since Freeze<Mock<IPizzaMap>>() would freeze a Mock<IPizzaMap>, but not IPizzaMap itself. On the other hand, Freeze<IPizzaMap>() wouldn't work because we haven't told the fixture how to create IPizzaMap instances, but even if we had, we wouldn't have a Mock<IPizzaMap> against which we could call Verify.

On the other hand, it's trivial to write an extension method to Fixture:

public static Mock<T> FreezeMoq<T>(this Fixture fixture) where T : class { var td = new Mock<T>(); fixture.Register(td.Object); return td; }

I chose to call the method FreezeMoq to indicate its affinity with Moq.

We can now rewrite the unit test from the previous post like this:

[TestMethod] public void AddWillPipeMapCorrectly_FreezeMoq() { // Fixture setup var fixture = new Fixture(); var basket = fixture.Freeze<Basket>(); var mapMock = fixture.FreezeMoq<IPizzaMap>(); var pizza = fixture.CreateAnonymous<PizzaPresenter>(); var sut = fixture.CreateAnonymous<BasketPresenter>(); // Exercise system sut.Add(pizza); // Verify outcome mapMock.Verify(m => m.Pipe(pizza, basket.Add)); // Teardown }

You may think that saving only a single line of code may not be that big a deal, but if you also need to perform Setups on the Mock, or if you have several different Mocks to configure, you may appreciate the encapsulation. I know I sure do.

Comments

You mentioned that adding an indirection between the tests and the SUT constructor helps with refactoring. But if I add a dependency to the SUT, I will still have to add calls to "fixture.Register" to fix my tests. And if I remove a dependency, then my tests will still work but the setup code will accumulate unnecessary cruft. It might be preferable to get a compiler error about a constructor argument which no longer exists.

My own approach for minimizing the impact of refactorings on tests is to just store the SUT and mocks as fields of the test class, and create them in the TestInitialize/SetUp method. That way there is only one place were the constructor is called.

Setting up your Test Fixture by populating fields on the test class is a common approach. However, I prefer not to do this, as it binds us very hard to the Testcase Class per Fixture pattern. Although it may make sense in some cases, it requires us to add new test classes every time we need to vary the Test Fixture even the slightest, or we will end up with a General Fixture, which again leads to Obscure Tests.

In my opinion, this leads to an explosion of test classes, and unless you are very disciplined, it becomes very difficult to figure out where to add a new test. This approach generates too much friction.

Even without AutoFixture, a SUT Factory is superior because it's not tied to a single test class, and if desirable, you can vary it with overloads.

The added benefit of AutoFixture is that its heuristic approach lets you concentrate on only the important aspects of a particular test case. Ideally, AutoFixture takes care of everything else by figuring out which values to supply for all those parameters you didn't explicitly supply.

However, I can certainly understand your concern about unnecessary cruft. If we need a long sequence of fixture.Register calls to register dependencies then we certainly only introduce another level of maintainance hell. This leads us into an area I have yet to discuss, but I also use AutoFixture as an auto-mocking container.

This means that I never explicitly setup mocks for all the dependencies needed by a SUT unless I actually need to configure it. AutoFixture will simply analyze the SUT's constructor and ask Moq (or potentially any another dymamic mock) to provide an instance. This approach works really well, but I have yet to blog about it because the AutoFixture API that supports automocking has not yet solidified. However, for hints on how to do this with the current version, see this discussion.

I think the following is what you meant (or maybe this article i

// does not work var td = new Mock(); fixture.Register(td.Object); // should work fixture.Inject(td.Object); fixture.Register(() => td.object);

Wes, thank you for writing. You are indeed correct that this particular overload of the Register method no longer exists, and Inject is the correct method to use. See this Stack Overflow answer for more details.

This article is out of date. Readers wishing to use AutoFixture with Moq should read AutoFixture as an auto-mocking container.

More about frozen pizza

In my previous blog post, I introduced AutoFixture's Freeze feature, but the example didn't fully demonstrate the power of the concept. In this blog post, we will turn up the heat on the frozen pizza a notch.

The following unit test exercises the BasketPresenter class, which is simply a wrapper around a Basket instance (we're doing a pizza online shop, if you were wondering). In true TDD style, I'll start with the unit test, but I'll post the BasketPresenter class later for reference.

[TestMethod] public void AddWillPipeMapCorrectly() { // Fixture setup var fixture = new Fixture(); var basket = fixture.Freeze<Basket>(); var mapMock = new Mock<IPizzaMap>(); fixture.Register(mapMock.Object); var pizza = fixture.CreateAnonymous<PizzaPresenter>(); var sut = fixture.CreateAnonymous<BasketPresenter>(); // Exercise system sut.Add(pizza); // Verify outcome mapMock.Verify(m => m.Pipe(pizza, basket.Add)); // Teardown }

The interesting thing in the above unit test is that we Freeze a Basket instance in the fixture. We do this because we know that the BasketPresenter somehow wraps a Basket instance, but we trust the Fixture class to figure it out for us. By telling the fixture instance to Freeze the Basket we know that it will reuse the same Basket instance throughout the entire test case. That includes the call to CreateAnonymous<BasketPresenter>.

This means that we can use the frozen basket instance in the Verify call because we know that the same instance will have been reused by the fixture, and thus wrapped by the SUT.

When you stop to think about this on a more theoretical level, it fortunately makes a lot of sense. AutoFixture's terminology is based upon the excellent book xUnit Test Patterns, and a Fixture instance pretty much corresponds to the concept of a Fixture. This means that freezing an instance simply means that a particular instance is constant throughout that particular fixture. Every time we ask for an instance of that class, we get back the same frozen instance.

In DI Container terminology, we just changed the Basket type's lifetime behavior from Transient to Singleton.

For reference, here's the BasketPresenter class we're testing:

public class BasketPresenter { private readonly Basket basket; private readonly IPizzaMap map; public BasketPresenter(Basket basket, IPizzaMap map) { if (basket == null) { throw new ArgumentNullException("basket"); } if (map == null) { throw new ArgumentNullException("map"); } this.basket = basket; this.map = map; } public void Add(PizzaPresenter presenter) { this.map.Pipe(presenter, this.basket.Add); } }

If you are wondering about why this is interesting at all, and why we don't just pass in a Basket through the BasketPresenter's constructor, it's because we are using AutoFixture as a SUT Factory. We want to be able to refactor BasketPresenter (and in this case particularly its constructor) without breaking a lot of existing tests. The level of indirection provided by AutoFixture gives us just that ability because we never directly invoke the constructor.

Coming up: more fun with the Freeze concept!

Comments

It's not clear from the example how using AutoFixture for DI keeps our tests testing object behavior better than setting up dependencies through the constructor or setters. I think it will suffer the same problems as we're examining private data. It has one benefit in that our public APIs remain pristine from adding in special-ctors/Setters for DI.

But hey, I'm going to play with this and see what happens. Thanks for the code sample!

Am I missing something?

==>Lancer---

http://ConfessionsOfAnAgileCoach.blogspot.com

[1]

[code]private readonly Basket basket;

private readonly IPizzaMap map;

public BasketPresenter(Basket basket, IPizzaMap map) // <-- redesign for DI

[/code]

AutoFixture Freeze

One of the important points of AutoFixture is to hide away all the boring details that you don't care about when you are writing a unit test, but that the compiler seems to insist upon. One of these details is how you create a new instance of your SUT.

Every time you create an instance of your SUT using its constructor, you make it more difficult to refactor that constructor. This is particularly true when it comes to Constructor Injection because you often need to define a Test Double in each unit test, but even for primitive types, it's more maintenance-friendly to use a SUT Factory.

AutoFixture is a SUT Factory, so we can use it to create instances of our SUTs. However, how do we correlate constructor parameters with variables in the test when we will not use the constructor directly?

This is where the Freeze method comes in handy, but let's first examine how to do it with the core API methods CreateAnonymous and Register.

Imagine that we want to write a unit test for a Pizza class that takes a name in its constructor and exposes that name as a property. We can write this test like this:

[TestMethod] public void NameIsCorrect() { // Fixture setup var fixture = new Fixture(); var expectedName = fixture.CreateAnonymous("Name"); fixture.Register(expectedName); var sut = fixture.CreateAnonymous<Pizza>(); // Exercise system string result = sut.Name; // Verify outcome Assert.AreEqual(expectedName, result, "Name"); // Teardown }

The important lines are these two:

var expectedName = fixture.CreateAnonymous("Name"); fixture.Register(expectedName);

What's going on here is that we create a new string, and then we subsequently Register this string so that every time the fixture instance is asked to create a string, it will return this particular string. This also means that when we ask AutoFixture to create an instance of Pizza, it will use that string as the constructor parameter.

It turned out that we used this coding idiom so much that we decided to encapsulate it in a convenience method. After some debate we arrived at the name Freeze, because we essentially freeze a single anonymous variable in the fixture, bypassing the default algorithm for creating new instances. Incidentally, this is one of very few methods in AutoFixture that breaks CQS, but although that bugs me a little, the Freeze concept has turned out to be so powerful that I live with it.

Here is the same test rewritten to use the Freeze method:

[TestMethod] public void NameIsCorrect_Freeze() { // Fixture setup var fixture = new Fixture(); var expectedName = fixture.Freeze("Name"); var sut = fixture.CreateAnonymous<Pizza>(); // Exercise system string result = sut.Name; // Verify outcome Assert.AreEqual(expectedName, result, "Name"); // Teardown }

In this example, we only save a single line of code, but apart from that, the test also becomes a little more communicative because it explicitly calls out that this particular string is frozen.

However, this is still a pretty lame example, but while I intend to follow up with a more complex example, I wanted to introduce the concept gently.

For completeness sake, here's the Pizza class:

public class Pizza { private readonly string name; public Pizza(string name) { if (name == null) { throw new ArgumentNullException("name"); } this.name = name; } public string Name { get { return this.name; } } }

As you can see, the test simply verifies that the constructor parameter is echoed by the Name property, and the Freeze method makes this more explicit while we still enjoy the indirection of not invoking the constructor directly.

Comments

I am trying to understand how, in this particular example, AutoFixture makes the set up impervious to changes in the constructor.

Say that for whatever reason the Pizza constructor takes another parameter e.g.

public Pizza(string name, price decimal)

Then surely, we'd have to update the test given. Am I missing something?

Try it out :)

Thanks for the prompt reply. Now, I think I understand what's going. Effectively, I was not appreciating that the purpose of "Freezing" was to have the string parameter "Name" "frozen" so that the assertion could be made against a known value.

But your explanation has clarified the issue. Thanks very much.

new Pizza(string fancyName, string boringName)

WesM, thank you for writing. Perhaps you'll find this article helpful.

CNUG TDD talk

As part of the Copenhagen .NET User Group (CNUG) winter and early autumn schedule, I'll be giving a talk on (slightly advanced) TDD.

The talk will be in Danish and takes place April 15th, 2010. More details and sign-up here.

Service Locator is an Anti-Pattern

Service Locator is a well-known pattern, and since it was described by Martin Fowler, it must be good, right?

No, it's actually an anti-pattern and should be avoided.

Let's examine why this is so. In short, the problem with Service Locator is that it hides a class' dependencies, causing run-time errors instead of compile-time errors, as well as making the code more difficult to maintain because it becomes unclear when you would be introducing a breaking change.

OrderProcessor example #

As an example, let's pick a hot topic in DI these days: an OrderProcessor. To process an order, the OrderProcessor must validate the order and ship it if valid. Here's an example using a static Service Locator:

public class OrderProcessor : IOrderProcessor { public void Process(Order order) { var validator = Locator.Resolve<IOrderValidator>(); if (validator.Validate(order)) { var shipper = Locator.Resolve<IOrderShipper>(); shipper.Ship(order); } } }

The Service Locator is used as a replacement for the new operator. It looks like this:

public static class Locator { private readonly static Dictionary<Type, Func<object>> services = new Dictionary<Type, Func<object>>(); public static void Register<T>(Func<T> resolver) { Locator.services[typeof(T)] = () => resolver(); } public static T Resolve<T>() { return (T)Locator.services[typeof(T)](); } public static void Reset() { Locator.services.Clear(); } }

We can configure the Locator using the Register method. A ‘real' Service Locator implementation would be much more advanced than this, but this example captures the gist of it.

This is flexible and extensible, and it even supports replacing services with Test Doubles, as we will see shortly.

Given that, then what could be the problem?

API usage issues #

Let's assume for a moment that we are simply consumers of the OrderProcessor class. We didn't write it ourselves, it was given to us in an assembly by a third party, and we have yet to look at it in Reflector.

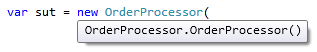

This is what we get from IntelliSense in Visual Studio:

Okay, so the class has a default constructor. That means I can simply create a new instance of it and invoke the Process method right away:

var order = new Order(); var sut = new OrderProcessor(); sut.Process(order);

Alas, running this code surprisingly throws a KeyNotFoundException because the IOrderValidator was never registered with Locator. This is not only surprising, it may be quite baffling if we don't have access to the source code.

By perusing the source code (or using Reflector) or consulting the documentation (ick!) we may finally discover that we need to register an IOrderValidator instance with Locator (a completely unrelated static class) before this will work.

In a unit test test, this can be done like this:

var validatorStub = new Mock<IOrderValidator>(); validatorStub.Setup(v => v.Validate(order)).Returns(false); Locator.Register(() => validatorStub.Object);

What is even more annoying is that because the Locator's internal store is static, we need to invoke the Reset method after each unit test, but granted: that is mainly a unit testing issue.

All in all, however, we can't reasonably claim that this sort of API provides a positive developer experience.

Maintenance issues #

While this use of Service Locator is problematic from the consumer's point of view, what seems easy soon becomes an issue for the maintenance developer as well.

Let's say that we need to expand the behavior of OrderProcessor to also invoke the IOrderCollector.Collect method. This is easily done, or is it?

public void Process(Order order) { var validator = Locator.Resolve<IOrderValidator>(); if (validator.Validate(order)) { var collector = Locator.Resolve<IOrderCollector>(); collector.Collect(order); var shipper = Locator.Resolve<IOrderShipper>(); shipper.Ship(order); } }

From a pure mechanistic point of view, that was easy - we simply added a new call to Locator.Resolve and invoke IOrderCollector.Collect.

Was this a breaking change?

This can be surprisingly hard to answer. It certainly compiled fine, but broke one of my unit tests. What happens in a production application? The IOrderCollector interface may already be registered with the Service Locator because it is already in use by other components, in which case it will work without a hitch. On the other hand, this may not be the case.

The bottom line is that it becomes a lot harder to tell whether you are introducing a breaking change or not. You need to understand the entire application in which the Service Locator is being used, and the compiler is not going to help you.

Variation: Concrete Service Locator #

Can we fix these issues in some way?

One variation commonly encountered is to make the Service Locator a concrete class, used like this:

public void Process(Order order) { var locator = new Locator(); var validator = locator.Resolve<IOrderValidator>(); if (validator.Validate(order)) { var shipper = locator.Resolve<IOrderShipper>(); shipper.Ship(order); } }

However, to be configured, it still needs a static in-memory store:

public class Locator { private readonly static Dictionary<Type, Func<object>> services = new Dictionary<Type, Func<object>>(); public static void Register<T>(Func<T> resolver) { Locator.services[typeof(T)] = () => resolver(); } public T Resolve<T>() { return (T)Locator.services[typeof(T)](); } public static void Reset() { Locator.services.Clear(); } }

In other words: there's no structural difference between the concrete Service Locator and the static Service Locator we already reviewed. It has the same issues and solves nothing.

Variation: Abstract Service Locator #

A different variation seems more in line with true DI: the Service Locator is a concrete class implementing an interface.

public interface IServiceLocator { T Resolve<T>(); } public class Locator : IServiceLocator { private readonly Dictionary<Type, Func<object>> services; public Locator() { this.services = new Dictionary<Type, Func<object>>(); } public void Register<T>(Func<T> resolver) { this.services[typeof(T)] = () => resolver(); } public T Resolve<T>() { return (T)this.services[typeof(T)](); } }

With this variation it becomes necessary to inject the Service Locator into the consumer. Constructor Injection is always a good choice for injecting dependencies, so OrderProcessor morphs into this implementation:

public class OrderProcessor : IOrderProcessor { private readonly IServiceLocator locator; public OrderProcessor(IServiceLocator locator) { if (locator == null) { throw new ArgumentNullException("locator"); } this.locator = locator; } public void Process(Order order) { var validator = this.locator.Resolve<IOrderValidator>(); if (validator.Validate(order)) { var shipper = this.locator.Resolve<IOrderShipper>(); shipper.Ship(order); } } }

Is this good, then?

From a developer perspective, we now get a bit of help from IntelliSense:

![]()

What does this tell us? Nothing much, really. Okay, so OrderProcessor needs a ServiceLocator - that's a bit more information than before, but it still doesn't tell us which services are needed. The following code compiles, but crashes with the same KeyNotFoundException as before:

var order = new Order(); var locator = new Locator(); var sut = new OrderProcessor(locator); sut.Process(order);

From the maintenance developer's point of view, things don't improve much either. We still get no help if we need to add a new dependency: is it a breaking change or not? Just as hard to tell as before.

Summary #

The problem with using a Service Locator isn't that you take a dependency on a particular Service Locator implementation (although that may be a problem as well), but that it's a bona-fide anti-pattern. It will give consumers of your API a horrible developer experience, and it will make your life as a maintenance developer worse because you will need to use considerable amounts of brain power to grasp the implications of every change you make.

The compiler can offer both consumers and producers so much help when Constructor Injection is used, but none of that assistance is available for APIs that rely on Service Locator.

You can read more about DI patterns and anti-patterns in my book.

Update 2014-05-20: Another way to explain the negative aspects of Service Locator is that it violates SOLID.

Update 2015-10-26: The fundamental problem with Service Locator is that it violates encapsulation.

Comments

I would like to hear your opinion, what do you think about a service locator that operates with dependency injection? So when you call the service locator it returns the requested type that was specified in the di wiring?

For instance.. many DI framework have trouble working without constructors as in .aspx, .asmx, .svc, how would you solve such scenario?

A hammer is only aprobiate when you need to hit on something.

Servicelocator is only useable if you need to create dynamic objects inside your class,

otherwise it really is an antipattern.

The right thing to do is use Injection where the dependency tree is fixed and ServiceLocator

where you are sure you need to dynamicaly create something new ( in a factory for ex. ).

Lately, I've been using AutoFac more and more which, I feel, helps with these type of problems by using delegate factories. Be interested to hear your thoughts on if this is a good compromise?

BTW, nice pimp of your book, I might buy it if it's all this thought provoking :)

In such cases you really have no recourse but to move the Composition Root into each object (e.g. Page) and let your DI Container wire up your dependencies from there. This may look like the Service Locator anti-pattern, but it isn't because you still keep container usage at an absolute minimum. The difference is that the 'absolute minimum' in this case is inside the constructor or Initialize method of each and every object (e.g. Page) created by the framework (e.g. ASP.NET).

At that point, we need to ask our DI Container to wire up the entire object graph for further use. This also means that we should treat the object where we do this as a Humble Object whose only responsibility is to act as an Adapter between the framework and our own code that uses proper DI patterns.

In ASP.NET, we can pull the container from the Application object so that we can have a single, shared container that can track long-lived (i.e. Singleton-scoped) dependencies without having to resort to a static container. This is by far the best option because there will be no 'virtual new operator' available further down the call stack - you can't call Locator.Resolve<IMyDependency>() because there will be no static container.

The Hollywood principle still applies to the rest of the application: Don't call the container, it'll call you. Instead of bootsrapping the application in one go from its entry point (as we can do in ASP.NET MVC) we need to bootstrap each created object individually, but from there on down, there will be no Service Locator available.

This is where Abstract Factories bridge the gap. What is better about an Abstract Factory compared to a Service Locator is that it is strongly typed: you can't just ask it for any dependency, but only for instances of specific types.

Thank you for your comment.

Missing IntelliSense and compiler support are just two symptoms of a poorly modeled object model. You are in your right to disagree, but I consider good API design to be as explicit as possible and adhere to the Principle of Least Astonishment. It really has nothing to do with whether I, as a developer, understand the Service Locator (anti-)pattern or not.

A good API should follow design principles for reusable libraries. It doesn't really matter whether you are building a true reusable library, or just a single application for internal use. If you want it to be maintainable, it must behave in a non-surprising and consistent manner, and not require you to have intimate knowledge of the inner workings of each class. This is one of the driving forces behind Domain-Driven Design, as well as such principles as Command-Query Separation.

Any class that internally uses a Service Locator isn't Clean Code because it doesn't communicate its intent or requirements.

Unit tests may help, but it would be symptomatic treatment instead of driving to the core of the problem. The benefit of unit testing is that it provides us with faster feedback than integration testing or systems testing would do. That's all fine, but the compiler provides even faster feedback, so why should I resort to unit testing if the compiler can give me feedback sooner?

Actually - `anti-pattern` is not an antonym to `pattern`. Pattern does NOT say that something is cool and good per se in every imaginable situation.

Conclusion:

while these are definitely correct and good points you make and everyone should be aware of them, we return back to those boring phrases like =>

"use right tool for the job"

and

"it depends..."

Thank you for writing.

At the risk of taking the discussion in the wrong direction, "AntiPatterns" [Brown et al., Wiley, 1998] define an anti-pattern as a "commonly ocurring solution to a problem that generates decidedly negative consequences" (p. 7). According to that definition, Service Locator is an anti-pattern.

The reason I insist on protracting this semantic debate is that I have yet to see a valid case for Service Locator. There may be occasions where we need to invoke container.Resolve from deeper in the application than we would ideally have liked (the ASP.NET case described above in point), but that isn't the Service Locator anti-pattern in play, but rather a set of distributed Composition Roots.

To me, Service Locator is when you use the Resolve method as a sort of 'virtual new operator', and that is just never the right tool for the job.

What's interesting - i started to feel like you - can't find reason for service locator.

Good thing is - you gave a great push. At least - for me. Currently - clearing out confusion about IoC in my head.

Bad thing is - learning process is still in progress and i haven't found feeling that 'i know' to wholeheartedly agree with you.

Must confess that I've used related tools and techniques without necessary knowledge. :)

Here's an interesting confession: There are a few places in Safewhere's production code where we call Resolve() pretty deep within the bowels of the application. You could well argue that we apply Service Locator there. The point, however, is that I still don't consider those few applications valid, but rather as failures on my part to correctly model our abstractions. One day, I still hope to get them right so I can get rid of those last pieces, and I actually managed to remove one dirty part of that particular API just this week.

We are all only fallible humans, but that doesn't stop me from striving towards perfection :)

And that abstract Factory is useing new xyz()?

No that Factory than needs the Servicelocator.

Concrete implementations of an Abstract Factory may very well need specific dependencies, which it can request via Constructor Injection - just like any other service.

The DI Container will then wire up the concrete factory with its dependencies just like it wires up any other service. No Service Locator is ever needed.

Here's just one example demonstrating what I mean.

This is similar to an abstract factory pattern, but it's much more feasible to implement when you have a ton of dependencies.

Additionally, if you consider a service oriented architecture where the services are well known and are always guaranteed to exist, but you just don't know where (could be on a separate server via WCF), then the service locator pattern solves a lot of problems.

Passing a ton of dependencies through dependency injection every time leads to unreadable code in my opinion. If by convention, the service is guaranteed to always exist, then Service Locator is a valuable pattern.

I would consider this to be an application of the Convention over Configuration paradigm.

However, it is a pattern that should only be used where it makes sense, I can see how abusing it would create more problems than it solves.

Modern IoC containers let you resolve dependencies at runtime without using service locator. Windsor for example has several places where you can plug in to provide the dependencies, DynamicParameters method or OnCreated are just two examples from the top of my head. More generic solutions like handler selectors or subdependencyresolvers also exist.

In cases where you do need to trigger resolution of a dependency from the call site many containers provide autogenerated abstract factories (Windsor has TypedFactoryFacility which creates interface based factories and in trunk (v2.5) also delegate based factories).

So in my opinion using SL is just an excuse for being lazy. The only place where I'd use it (temporarily) is when migrating old, legacy code that can't be easily changed, as an intermediate step.

The strength or weakness of your choice and use of patterns depends on how they meet your requirements. There is no one golden way. Dependency Injections is not a cure all nor was service locator when it became widely used. I use both and many others.

And how many patterns can you fit into the definition of "Anti-Pattern" if it is misused / abused?

In my opinion the SOA discussion is completely orthogonal to the discussion about the Service Locator (anti-)pattern. We shouldn't be misled by the similarity of names. The services located by a Service Locator are object services that may or may not encapsulate or represent an external resource. That external resource may be a web service, but could be something entirely different. When we discuss the Service Locator (anti-)pattern, we discuss it in the context of object-oriented design. Whether or not the underlying implementation is a web service is irrelevant at that level.

That said, I'm fully aware that many SOA environments work with a service registry. UDDI was the past attempt at making this work, while today we have protocols such as WS-Discovery. These can still be considered implementations of 'design patterns', but they certainly operate on a different architectural level. They have nothing to do with the Service Locator (anti-)pattern.

Nothing prevents us from combining proper Dependency Injection with service registries. They are unrelated because they operate at different levels, so they can be combined with exact the same flexibility as data access and UI technologies.

If we go back to the (original?) definition of the term anti-pattern from the book, an anti-pattern is characterized by a "commonly occurring solution to a problem that generates decidedly negative consequences". By that definition, Service Locator is an anti-pattern - even if you can come up with niche scenarios where it makes sense. So far, I've never been presented with a case for Service Locator where I haven't been able to come up with a better design that uses proper DI.

I first learned how to prepare sauce béarnaise when I started making Sole Wellington.

Reading book now, nice.

Cheers,

Karl

If I go directly the posted definition of anti-pattern, which most can agree with, I can put a number of patterns that are not always anti-patterns in this category. I tend to emphasize proper pattern usage. Patterns are just tools that can be correctly or incorrectly. I have seen design-by-contract (interface pattern) used in a manner that fits the anti-pattern definition but I don't consider it an anti-pattern. I consider the use of pattern poor or inappropriate for that situation.

I consider SOA != Web services + UDDI + etc,. Web services and its relative technology stack can be used to implement an SOA. Therefore, from my perspective it is relative to this discussion and not orthogonal. In fact we had a discussion relative to these to these concepts last week in one of my current projects. The goal of that discussion was the abstraction of service implementation + location in a high-performance low-latency SOA design.

I am not a proponent of Service Locator or any other pattern. I us it and others with/without DI where appropriate. The perceived / actual negative impact of a pattern usage in one scenario does not apply to all scenarios. There are definitely patterns where one can get a majority agreement on them being anti-patterns. I just don't think Service Locator is one. However, the pursuit of try to qualify the validity of a pattern's usage or existence does generally lead to other solutions or ideas. Which I am a proponent of.

Cheers,

Iran

Service locator and DI, have essentially the same main downsides, and the only real difference is whether you prefer to retrieve the component from your code of to have it injected externally. In fact, and at least in the Java implementations i have worked with, you get less compiler support with DI variants, and also have a harder time to debug because of faulty injections. I am still amazed to see people arguing about how you get a dependency with a particular service locator implementation, when you a) can have a light wrapper to decouple from it and b) you get the same dependency with your particular DI implementation, you still have to tell de container what, how and when you need the injection, and thats a change too.

With you service locator example, you have only proved that it is also possible to write a crappy service locator implementation. And your moans are about that, not the pattern.

Though, how many developers with good will and at least, average knowledge are trying to use IoC just to fail to understand how to set up their root components and bootstrap correctly their dependencies?

Now, imagine those who understand well those principles and techniques, trying to explain, guide, support an entire team of developers about those concepts...I guess you see (or have seen) like me those astonished developers faces trying to understand and not mess this magic behind dependency injection.

Ok, I'll admit it is not so hard. But still, my point is it is much harder to understand how those dependencies are injected and how not to mess and miss the point than using a simple Service locator instead of a "new" keyword.

And as someone else mention before, it is mandatory to use a Service locator with good convention-over-configuration to have fun with it. But it is the same with Dependency injection.

I see service locator as a first step for a team into IoC. After the concept and benefits are known by the team, I think it is much easier to turn the ship towards the Dependency injection final destination.

Good article and back and forth discussions here

Thanks

Phil

FWIW the first nine chapters of my book discuss DI mainly in the context of Poor Man's DI (that is, without containers).

thanks for you answer, I was subconsciously avoiding this concept of Composition Root, although I didn't know why. But today I came to some code that shed some light on it, and the driving force against using the entry point for dependecies instantiation was my understanding of "encapsulation". As I see it, some dependencies should not be known outside the object. The code I mentioned, for instance, is a class named "Syncronizer" which defines a sequency of "Steps" (each step is an object), the sequence and steps are defined internally and it is the Syncronizer's sole responsibility, chosen steps are "instantiated" internally (say 10 of 30 available), The entry point isn't aware of which Steps would be needed. AS I see, there is something in DI that goes against "encapsulation". Would love to know your thoughts about it.

Alex Brina

1. Passing around the container was obviously the wrong approach

2. A global, static container also "felt" like the wrong approach... the business code shouldn't need to know that much about the application domain.

3. A very common solution around the web is the ServiceLocator pattern, but - the reason I continued looking is that pattern just "felt" wrong to me in an intuitive sense - it's essentially no better than (2) and as you say, the container begins to invade the business logic. Now, the entire architecture has to know about the container - which completely defeats the purpose of DI and IoC.

So then I stumbled upon your post and it summed up EXACTLY why those approaches "felt" wrong - and also helped me re-orient my thinking with regard to where to create the containers.

I don't NEED a single container for the whole application, I only need them within the scope where they're required. If I have a type that is only ever instantiated 4 levels deep in the object hierarchy, it makes no difference whether I register the type at the root of the application or scoped to the code where that type is relevant. Thus, in order to prevent the container from invading the application in the ways you describe, it makes perfect sense to create the container at a lower level (what you call the Composition Root?).

Really like your blog. I appreciate the dedication to design principles that seem so easily thrown away when pragmatism requires.

An error has been encountered while processing the page. We have logged the error condition and are working to correct the problem. We apologize for any inconvenience.

Page rendered at Wednesday, July 13, 2011 8:02:11 AM (Romance Daylight Time, UTC+02:00)

Sorry about the inconvenience.

Apologies for the necromancy, but I googled for 'Service Locator anti pattern' and this post is one of the top-five hits.

I totally agree that Service Locator is an anti-pattern. It's the use of the static class/property that makes it so insidious. It's an example of a Skyhook (http://garymcleanhall.wordpress.com/2011/07/24/skyhooks-vs-cranes/) as opposed to DI, which is a Crane.

Service Locator seems to be preferred because the alternative is sometimes to write a constructor to inject half a dozen (or more) dependencies, ie: it smells like the class has too many responsibilities.

http://googletesting.blogspot.com/2008/11/clean-code-talks-dependency-injection.html

API Usage Issue:

In the case of both IOC and Service locator, there is an independent class that is responsible for making sure that the appopriate service (IOrderValidator or IOrderShipper) is found by the client. The only difference is whether the client automatically receives the information or if the client makes an explicit call to a 3rd party class (Locator) to find it. It is more a semantic argument than anything else.

If the configuration of the IOC is done incorrectly, you will also receive an exception. The problem is with the management of the configuration as opposed to the service locator itself.

Maintenance Issues:

Same problem as above. This is a problem with configuration of the service as opposed to the way in which IOC or service locator is used.

With both service locator and IOC, someone is going to have to understand all the dependencies in order to configure the services correctly and ensure that the correct service is returned when called upon. This configuration is part of the setup of the service contract. Whether or not this configuration is done through an IOC container or through a service locator seems immaterial.

Sorry, I cannot agree with author’s statements from practical standpoint. If you discuss pure theory and your team has unlimited resources for your projects - you can use all kind of nice patterns that require more work and give some advantage.

Let's compare advantages and disadvantages and not just talk about pros on one side.

I talk from practical large scale software Dev experience when your product is not one-man show but you have mature product with a lot of components, several teams, and engineers coming and leaving. Is it what we all try to get to? If you are talking about one-man show project or small-highly-skilled team project and you work on v1 or v1.1 of your product - sure you can use any pattern and dependency injection through constructor parameters would probably work for you.

===========================

== Service Locator advantages ==

1. Much smaller production code. No need to declare variables, parameters to pass dependencies, properties for stateful objects, etc.

Every line of code/symbol has associated Dev/QA/support cost. Smaller code is easier to understand and update.

2. Much smaller unit test code. No need to instantiate and pass dependencies - you can set all common dependencies in TestSetup and reset them in TestCleanup. Again, every line of code/symbol has associated cost.

3. Much easier to introduce dependencies. Yes, this is an advantage, because you need to write much less code for this if you use Service Locator. And again every line of code....

Imagine you need to add SQL performance logger deep in the code and of course you want all your DB access methods use the same logger instance no matter how you get there from business logic layer. You have to change all stack of callers if you do not use Service Locator.

And if you have to change any caller because of your method change -this can be a huge problem in mature product. There will be no way you can justify expenses for a new release of the calling component to you management.

== Service Locator disadvantages ==

1. Introduced dependencies are not captured at compile time.

How to fix this? The answer is - test your product (with automatic integration or manual tests). But you have to test only changed functionality to make sure that feature that uses new introduced dependency works correctly. You need this anyway and this is already in the plan/budget for your project/change anyway.

Did I miss anything?

===========================

We’ve tried to use dependency injection and switch to Service Locator turned out to be such a huge relief

that we would never even consider switching back.

== My conclusion ==

If you are working on long-term project and you have to implement cost-efficient solution, maintainable by the team with various skill levels - Service Locator is significant cost saver for you with small to none down sides.

If quality is your first priority and budget/time-to-market is not an issue and you have skilled team - do not use Service Locator and rely as much as possible on compile time checks.

We could say the container itself should not be a dependency, and hance should not be passed around, as stated in this StackOverflow question.

http://stackoverflow.com/questions/4806918/should-i-be-passing-a-unity-container-in-to-my-dependencies

To me, Service Locator is the exact opposite of Inversion of Control.

http://stackoverflow.com/questions/2386487/is-it-better-to-create-a-singleton-to-access-unity-container-or-pass-it-through is another great StackOverflow question about this topic (no surpsise the correct answer is by Mark Seemann himself.

Do people apply it in less then optimal scenarios? Absolutely. Does that make a pattern, an anti-pattern? Absolutely not.

(I've had to remove angle brackets so I hope the code still makes sense.. where you see a T think generics T with angle brackets:))

All you are doing with your proposal is turning the abstract factory into an "anti-pattern". Why go through the creation of the factory only to create a new level of indirection just to (essentiall)resolve 1 object that needs resolution in 1 one. I know you can reuse this everywhere. Why not create an object registry interface eg IMyObjectRegistry

eg:

public interface IMyObjectRegistry { T get_for T ();}

public class MyObjectRegistry : IMyObjectRegistry {

public T get_for T (){

return Resolver.Get T ();

}

}

IMyObjectRegistry get passed around. You could also further constrain these to only work with certain types.

You register the "Registry" with the DI container. Now all objects have a way of finding dependencies with the ServiceLocator. Its still very testable you can Mock/Stub/Fake IMyObjectRegistry. You don't even need a DI implementation in your tests.

It is the Service Locator's responsibilty to RESOLVE the interface implementation, if the interface is not registered, instead of doing NOTHING which bubble's KeyNotFoundException up, it should raise its own exception to notify consumer that the interface has NOT been registered yet.

I think you fail to understand the argument against ServiceLocator. No one is debating what ServiceLocator's responiblities are.

This problem with ServiceLocator is the problems/headaches it introduces. The biggest one being that it hides a type's dependencies.

It's difficult to write unit tests for a type when it isn't clear from the type's contract what type of dependencies it has. This can make writing unit tests extremely painful and discouraging. Secondly, it make detecting breaking changes a PITA. That fact that your unit test fails because some hidden dependency hasn't been resolved is a side-effect of ServiceLocator.

Unfortunately, when some developers hear the word 'pattern' they automatically assume it's good/best practice. This is hardly the case with ServiceLocator. A pattern that makes your life harder or encourages bad design practices is an anti-pattern.

So your normal answer is "abstract factory", but that still would mean an additional parameter. Should I inject an ILogger or ILoggerAbstractFactory into EVERY class? That.. would be insane.

So what's your solution there?

As you well argue, "expressing intention" in design is amongst the main points of DI. But ILogger is an cross-cutting concern, showing intention to log in a class is 0% Info to anyone (as is tracing). I know these are the most used examples for AOP, but I repeat myself: AOP doesn't solve logging additional/debug info, just exception logging. Or I'm misunderstanding AOP capabilities.

1) it doesn't know its scope (app domain, thread, call context, or custom context)

2) it doesn't know when to dispose itself. Both problems come from the fact that it's the root application that should care about those problems.

Again it comes down to Service Locator.

Did you read the Ambient Context pattern description in my book?

Most loggers already come with an Ambient Context implementation. Logger.Log("foo") is, essentially, an Ambient Context. It's true that it's not particularly clear when an Ambient Context should dispose itself, but then again: why would you need to dispose of something which is a cross-cutting concern? I'd prefer such a thing to stick around (for performance reasons).

Still, if you don't like Ambient Context (I don't), you can always use an Abstract Factory to get your ILogger. Service Locator is not required.

Dispose problems come with asp.net doing threads reuse. Though CallContext can be used as workaround, it feels a bit hacky.

It's easier with loggers as they usually can be just static. But if I need something to be bound to a HttpContext or a session?

Abstract factory doesn't solve the problem this all started with: extra reference in a constructor. IoC looks very nice when my classes have parameters they really need to do their work. But secondary parameters like ILogger or ILoggerFactory don't make much sense. If I went this way I would prefer something like IInfrastructure and let it have all ILogger properties and other cross cutting stuff.

I still don't feel satisfied with all solutions. I don't like that SL hides contracts, but I also don't like that DI makes them over complicated.

I agree that injecting an ILoggerFactory could be considered as parameter pollution of the constructor, but remember that (IMO) we are only talking about this as a solution when dealing with legacy code. Properly factored code should have methods that are short enough that a Decorator or Around Advice should be more than enough for logging and instrumentation purposes.

So once again: Service Locator is never a solution for anything. The solution is to refactor the code so that you don't need to inject an ILogger at all.

am desparately in need of a help, I tried to post my complete content (with code) but it was always throwing an error, Have sent you an email, request you to please review and share your thoughts.

Thanks,

Tarriq

public class MyService

{

public MyService (IRepository1 repository, IRepository2 repositor2)

...

public void DoStuff ()

{

repository.Find...

repository2.QueryAllWithCriteria...

...

}

}

And code 2:

public class MyService

{

public void DoStuff ()

{

// used square brakets instead of angle

// cause of comment posting error

ServiceLocator.Resolve[IRepository1].Find...

ServiceLocator.Resolve[IRepository2].QueryAllWithCriteria...

...

}

}

Since when injecting dependencies (code 1) is helping understand better on on which code MyService really depends compared to code 2? I mean real world repositories usually have a lot of different methods. Just because you pass it around does not help user understand which method inside that repository the service use. For example, if I'm going to write unit test it won't help my at all - unless I got some really simple/generic repository I can't just mock all repository methods just to test my service. So I still end up looking into the code or catching first run test failures to see what I need to mock inside that repository. And no - SRP has nothing to do with it, unless you plan to build separate repository for every single query/operation.

Why then I should clutter my client code with pointless stuff?

For example, I develop a library for internal usage between many projects. It exports some services, command and queries. It does not work with some external repositories - so why should I make all users to pass my repositories to my methods? I could just make them call one single bootstrapper static method during app startup which will register all my necessary components for my library to work.

Service locator is ideal thing for allowing loose coupling of internal components (for ability to unit test them).

And the second question - why do client (consumer of my library) have to deal with my internals? I mean why does he had to provide my service my repositories?

I think the whole misconception and negativism toward service locator comes from trying to use it everywhere and thus leaking it outside of your domain. Look at those many good libraries - they don't ask us to provide instances of their internals. In order to use NHibernate you have to configure it once and not feeding every session creation bunch of interface instances which it will use. NHibernate will use configuration to get instance of internal object when he needs to - that's basically the service locator with different name.

I think that real anti-patterns are:

1. Usage of constructor or property injection for external interfaces of your domain, that is expecting user to provide instances of interfaces that your service need in order to operate. Though it's good to provide a way for user to override some part implementaion (like NHibernate, MVC does).

2. Usage of service locator for external resources: if your service mean to operate on some external user-provided source you should never expect it to be provided via service locator - use constructor/properties/parameters injection instead.

I also suggest a way to amend service locator pattern to overcome dependency opacity in the clients of a locator. I apologize for the code might be a little long. But I'm sure you'll instantly get the idea behind it with in a glance.

best regards

p.s.: I wasn't able to submit the comment because the blog-engine takes angle brackets as xss attack. So I've changed all "lower than" and "greater than" characters into "dollar sign" ($) and "pound sign" (#) respectively. If you perform a replace-all in the code against these characters in reverse direction, the code turns back to normal.

public interface IDependency1 { }

public interface IDependency2 { }

public interface IClient

{

KeyValuePair$Type, bool#[] GetDependencies();

bool IsReady();

}

public interface IServiceLocator

{

void Register$T#(Func$T# resolver);

T Resolve$T#();

bool Contains$T#();

}

public class ServiceLocator: IServiceLocator

{

private readonly Dictionary$Type, Func$object## services = new Dictionary$Type, Func$object##();

public void Register$T#(Func$T# resolver)

{

services[typeof(T)] = () =# resolver();

}

public T Resolve$T#()

{

return (T)services[typeof(T)]();

}

public bool Contains$T#()

{

return services.Keys.Contains(typeof(T));

}

}

public class MyService: IClient

{

private bool hasIDependency1;

private bool hasIDependency2;

public MyService() { }

public MyService(IServiceLocator servicelocator, bool checkDependencies = false)

{

hasIDependency1 = servicelocator.Contains$IDependency1#();

hasIDependency2 = servicelocator.Contains$IDependency2#();

if (checkDependencies)

{

if (!hasIDependency1)

throw new ArgumentException("ServiceLocator doesn't resolve dependency: IDependency1.");

if (!hasIDependency2)

throw new ArgumentException("ServiceLocator doesn't resolve dependency: IDependency2.");

}

}

public KeyValuePair$Type, bool#[] GetDependencies()

{

var result = new KeyValuePair$Type, bool#[]

{

new KeyValuePair$Type, bool#(typeof(IDependency1),hasIDependency1),

new KeyValuePair$Type, bool#(typeof(IDependency2),hasIDependency2)

};

return result;

}

public bool IsReady()

{

return hasIDependency1 && hasIDependency2;

}

}

public class Test

{

public static void Main()

{

var ms = new MyService();

Console.WriteLine("Dependencies of 'MyService':");

Console.WriteLine(" Dependency Resolved");

Console.WriteLine("---------------------------------");

foreach(var item in ms.GetDependencies())

{

Console.WriteLine(item.Key + " " + item.Value);

}

Console.ReadKey();

}

}

/*

Dependencies of 'MyService':

Dependency Resolved

---------------------------------

Dummy.IDependency1 False

Dummy.IDependency2 False

*/

[blockquote cite="Scott"]

...

What does this tell us? Nothing much, really. Okay, so OrderProcessor needs a ServiceLocator – that’s a bit more information than before, but it still doesn’t tell us which services are needed.

[/blockquote]

... I suggested a solution by which a class can "report" if the given locator "contains" its required dependencies or not. So this way the OrderProcessor can tell us exactly which services are needed.

I agree with you completely. I've read this article and others like it concerning the Service Locator Anti-pattern. I've also read your book on dependency injection (I read it in a night, great book!). There is one topic that I would love to get your input on and that's the way in which Microsoft's Prism passes the Unity container around to each module for registering it's dependencies. For those who aren't familiar with Prism, it's a library from the Microsoft patterns and practices camp and it facilitates writing loosely coupled applications.

In prism your application is made up of independent modules that implement the IModule interface. Modules can be configured fluidly in code, defined in the application configuration file, and even discovered on demand from the file system. The IModule implementation allows for passing the IUnityContainer used throughout the application in each module's constructor to allow the module to register it's dependencies. Though I love the flexibility of the Prism Modules, I can't help but feel dirty about the way that the container is passed around sporadically to each module. I as a developer don't know what the developer of the next module to be initialized may do to the container. To me, this mystery aspect of the way that the container is used is strikingly similar to the problems of the Service locator anti-pattern. I feel that I need an "intimate knowledge" of the other modules if I want to be sure about the container. I'm curious about your thoughts on this subject considering you wrote the book :)

Thanks for your time, and keep up the great work!

Buddy James

One major problem with Service Locator is that it doesn't provide feedback until at run-time. It's much better if we can get feedback already at compile time, and that's possible with Dependency Injection. It 'reports' on its requirements at compile time. It also enables tools (such as DI Containers) to walk up to the type information and start querying about its dependencies.

The proposed fix for Service Locator doesn't change any of that. What benefits does it provide?

--In IIocAdapter:

T TryGet[T]( T defaultInstance, bool register = true );

--In AutofacIoc implementation:

public T TryGet[T]( T defaultInstance, bool register = true )

{

var instance = TryGet[T]();

if( null == instance )

{

instance = defaultInstance;

if( null != instance && register )

{

ContainerBuilder builder = new ContainerBuilder();

builder.RegisterType( instance.GetType() ).As( typeof( T ) );

builder.Update( m_Service );

}

}

return instance;

}

--And in the static Ioc "Service locator":

public static T TryGet[T]( T defaultInstance, bool register = true )

{

if( IsInitialized() )

return Adapter.TryGet[T]( defaultInstance, register );

return defaultInstance;

}

--From code:

public virtual IRuleContainer GetRuleContainer()

{

if( null == m_RuleContainer )

{

lock( LOCK )

{

if( null == m_RuleContainer )

m_RuleContainer = Ioc.TryGet[IRuleContainer]( new DefaultRuleContainer() );

}

}

return m_RuleContainer;

}

Very flexible. I can use IoC or inheritance.

I love it. It lets me create good default behavior that can be very simply replaced. It also makes the principle of "prefer containment over inheritance" much easier to achieve. I guess sometimes we need to use "anti-patterns" to enhance the implementation of other patterns.

So I conclude it this way:

Inability to report on compile-time is one other deficiency to Service Locator pattern among its other deficiencies.

While my suggestion may ease finding the requirements of the holder class a little, easier than a try-and-error approach such as using a try/catch, but the need to "execute" the app and obtaining the information at runtime is never removable.

Perhaps the only benefit for adding query API to a service locator is in those scenarios where you are extending an app whose structure, libraries and API is already fixed (perhaps worked by a previous team) and you can't modify those classes and method signatures.

Thank you for time on reviewing my code.

The way MEF works comes to mind, but you can do the same as MEF does with convention-based wiring with any DI Container worth its salt. However, I think I need to do a write-up of this one day...

The fundamental thing to be aware of, however, is that if you are building an application with a true add-in architecture, you'll need to define your interfaces in such a way that any dependency can be implemented by zero to many classes. The cardinality of dependencies in an add-in architecture is never 1, it's always 0+. Doing this elegantly addresses the issue of 'what if one module overwrites the other?' They mustn't be allowed to do that. All modules have equal priority, and so must their dependencies. This also makes a lot of sense if you think about what an add-in is: usually, it's just a file you drop in a folder somewhere, so there's no explicit order or priority implied.

Danyil, thank you for writing. Context IoC, as described in that article, isn't service location, because each context injected is only a limited, well-known interface. A Service Locator, on the other hand, exposes an infinite set of services.

That said, how does Context IoC solve anything that Pure DI doesn't solve in a simpler way?

To give my question above some context, I've run into online discussion threads where the participants equated the two, which I thought unfairly ignored the Context IoC pattern's better static guarantees. I am glad to hear you disagree with them on the matter of classification.

As for Pure DI, I will have to investigate it further. Thanks for your reply!

Danyil, thank you for writing. That Pure DI link may not give you the most succinct picture of what I had in mind. Using the blue/red example from the Context IoC article, you can rewrite MyService much simpler using Constructor Injection: