Functional file system by Mark Seemann

How do you model file systems in a functional manner, so that unit testing is enabled? An overview.

One of the many reasons that I like functional programming is that it's intrinsically testable. In object-oriented programming, you often have to jump through hoops to enable testing. This is also the case whenever you need to interact with the computer's file system. Just try to search the web for file system interface, or mock file system. I'm not going to give you any links, because I think such questions are XY problems. I don't think that the most common suggestions are proper solutions.

In functional programming, anyway, Dependency Injection isn't functional, because it makes everything impure. How, then, do you model the file system in such a way that it's pure, decoupled from the logic you'd like to add on top of it, and still has enough fidelity that you can perform most tasks?

You model the file system as a tree, or a forest.

File systems are hierarchies #

It should come as no surprise that file systems are hierarchies, or trees. Each logical drive is the root of a tree. Files are leaves, and directories are internal nodes. Does that sound familiar? That sounds like a rose tree.

Rose trees are immutable data structures. It doesn't get much more functional than that. Why not use a rose tree (or a forest) to model the file system?

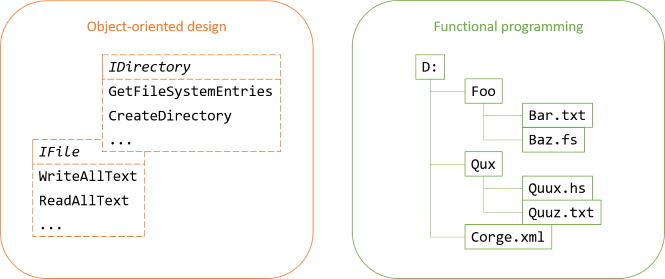

What about interaction with the actual file system? Usually, when you encounter object-oriented attempts at decoupling an abstraction from the actual file system, you'll find polymorphic operations such as WriteAllText, GetFileSystemEntries, CreateDirectory, and so on. These would be the (mockable) methods that you have to implement, usually as Humble Objects.

If you, instead of a set of interfaces, model the file system as a forest, interacting with the actual file system is not even part of the abstraction. That's a typical shift of perspective from object-oriented design to functional programming.

In object-oriented design, you typically attempt to model data with behaviour. Sometimes that fits the underlying reality well, but in this case it doesn't. While you have file and directory objects with behaviour, the actual structure of a file system is implicit. It's hidden in the interactions between the objects.

By modelling the file system as a tree, you explicitly use the structure of the data. How you load a tree into program memory, or how you imprint a tree unto the file system isn't part of the abstraction. When it comes to input and output, you're free to do what you want.

Once you have a model of a directory structure in memory, you can manipulate it to your heart's content. Since rose trees are functors, you know that all transformations are structure-preserving. That means that you don't even need to write tests for those parts of your application.

You'll appreciate an example, I'm sure.

Picture archivist example #

As an example, I'll attempt to answer an old Code Review question. I already gave an answer in 2015, but I'm not so happy with it today as I was back then. The question is great, though, because it explicitly demonstrates how people have a hard time escaping the notion that abstraction is only available via interfaces or abstract base classes. In 2015, I had long since figured out that delegates (and thus functions) are anonymous interfaces, but I still hadn't figured out how to separate pure from impure behaviour.

The question's scenario is how to implement a small program that can inspect a collection of image files, extract the date-taken metadata from each file, and move the files to a new directory structure based on that information.

For example, you could have files organised in various directories according to motive.

You soon realise, however, that that archiving strategy is untenable, because what do you do if there's more than one type of motive in a picture? Instead, you decide to organise the files according to month and year.

Clearly, there's some input and output involved in this application, but there's also some logic that you'd like to unit test. You need to parse the metadata, figure out where to move each image file, filter out files that are not images, and so on.

Object-oriented picture archivist #

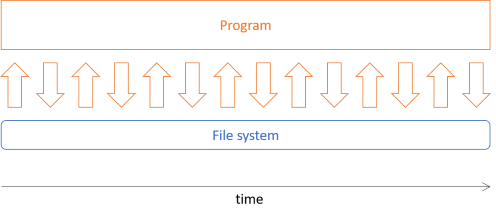

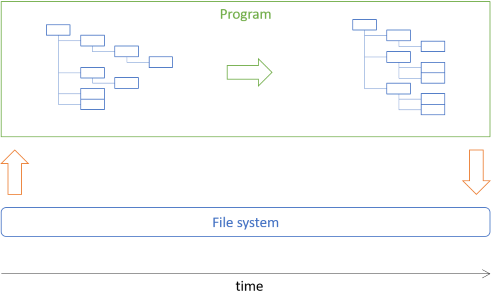

If you were to implement such a picture archivist program with an object-oriented design, you may use Dependency Injection so that you can 'mock' the file system during unit testing. A typical program might then work like this at run time:

The program has fine-grained, busy interaction with the file system (through a polymorphic interface). It'll typically read one file, load its metadata, decide where to put the file, and copy it there. Then it'll move on to the next file, although it might also do this in parallel. Throughout the program execution, there's input and output going on, which makes it difficult to isolate the pure from the impure code.

Even if you write a program like that in F#, it's hardly a functional architecture.

Such an architecture is, in theory, testable, but my experience is that if you attempt to reproduce such busy, fine-grained interaction with mocks and stubs, you're likely to end up with brittle tests.

Functional picture archivist #

In functional programming, you'll have to reject the notion of dependencies. Instead, you can often resort to the simple architecture I call an impure-pure-impure sandwich; here, specifically:

- Load data from disk (impure)

- Transform the data (pure)

- Write data to disk (impure)

When the program starts, it loads data from disk into a tree. It then manipulates the in-memory model of the files in question, and once it's done, it traverses the entire tree and applies the changes.

This gives you a much clearer separation between the pure and impure parts of the code base. The pure part is bigger, and easier to unit test.

Example code #

This article gave you an overview of the functional architecture. In the next two articles, you'll see how to do this in practice. First, I'll implement the above architecture in Haskell, so that we know that if it works there, the architecture does, indeed, respect the functional interaction law.

Based on the Haskell implementation, you'll then see a port to F#.

These two articles share the same architecture. You can read both, or one of them, as you like. The source code is available on GitHub.Summary #

One of the hardest problems in transitioning from object-oriented programming to functional programming is that the design approach is so different. Many well-understood design patterns and principles don't translate easily. Dependency Injection is one of those. Often, you'll have to flip the model on its head, so to speak, before you can take it on in a functional manner.

While most object-oriented programmers would say that object-oriented design involves focusing on 'the nouns', in practice, it often revolves around interactions and behaviour. Sometimes, that's appropriate, but often, it's not.

Functional programming, in contrast, tends to take a more data-oriented perspective. Load some data, manipulate it, and publish it. If you can come up with an appropriate data structure for the data, you're probably on your way to implementing a functional architecture.

Next: Picture archivist in Haskell.