Coupling from a big-O perspective by Mark Seemann

Don't repeat yourself (DRY) implies O(1) edits.

Here's a half-baked idea: We may view coupling in software through the lens of big-O notation. Since this isn't yet a fully-formed idea of mine, this is one of those articles I write in order to learn from the process of having to formulate the idea to other people.

Widening the scope of big-O analysis #

Big-O analysis is usually described in terms of functions on ℝ (the real numbers), such as O(n), O(lg n), O(n3), O(2n) and so on. This is somewhat ironic because when analysing algorithm efficiency, n is usually an integer (i.e. n ∈ ℕ). That, however, suits me fine, because it establishes precedence for what I have in mind.

Usually, big-O analysis is applied to algorithms, and usually by measuring an abstract notion of an 'instruction step'. You can, however, also apply such analysis to other aspects of resource utilization. Even within the confines of algorithm analysis, you may instead of instruction count be concerned with memory consumption. In other words, you may analyze an algorithm in order to determine that it uses O(n2) memory.

With that in mind, nothing prevents you from widening the scope further. While I tend to be disinterested in the small-scale performance optimizations involved with algorithms, I have a keen eye on how it applies to software architecture. In modern computers, CPU cycles are fast, but network hops are still noticeable to human perception. For example, the well-known n+1 problem really just implies O(n) network calls. Given that a single network hop may already (depending on topology and distance) be observable, even moderate numbers of n (e.g. 100) may be a problem.

What I have in mind for this article is to once more transplant the thinking behind big-O notation to a new area. Instead of instructions or network calls, let O(...) indicate the number of edits you have to make in a code base in order to make a change. If we want to be more practical about it, we may measure this number in how many methods or functions we need to edit, or, even more coarsely, the number of files we need to change.

Don't Repeat Yourself #

In this view, the old DRY principle implies O(1) edits. You create a single point in your code base responsible for a given behaviour. If you need to make changes, you edit a single part of the code base. This seems obvious.

What the big-O perspective implies, however, is that a small constant number of edits may be fine, too. For instance, 'dual' coupling, where two code blocks change together, is not that uncommon. This could for example be where you model messages on an internal queue. Every time you add a new message type, you'll need to define both how to send it (i.e. what data it contains and how it serializes) and how to handle it. If you are using a statically typed language, you can use a sum type or Visitor to keep track of all message types, which means that the type checker will remind you if you forget one or the other.

In big-O notation, we simplify all constants to 1, so even if you have systematic, but constant, coupling like this, we would still consider it O(1). In other words, if your architecture contains some coupling that remains constant, we may deem it O(1) and perhaps benign.

This also suggests why we have a heuristic like the rule of three. Dual duplication is still O(1), and as long as the coupling stays constant, there's no evidence that it's growing. Once you make the third copy does evidence begin to suggest that the coupling is O(n) rather than O(1).

Small values of 1 #

Big-O notation is concerned with comparing orders of magnitude, which is why specific constants are simplified to 1. The number 1 is a stand-in for any constant value, 1, 2, 10, og even six billion. When editing source code, however, the actual number of edits does matter. In the following sections, I'll give concrete examples where '1' is small.

Test-specific equality #

The first example we may consider is test-specific equality. My first treatment related to this topic was in 2010, and again in 2012. Since then, I've come to view the need for test-specific equality as a test smell. If you are doing test-driven development (which you chiefly should), giving your objects or values sane equality semantics makes testing much easier. And a well-known benefit of test-driven development (TDD) is that code that is easy to test is easy to use.

Still, if you must work with mutable objects (as in naive object-oriented design), you can't give objects structural equality. And as I recently rediscovered, functional programming doesn't entirely shield you from this kind of problem either. Functions, for example, don't have clear equality semantics in practice, so when bundling data and behaviour (does that sound familiar?), data structures can't have structural equality.

Still, TDD suggests that you should reconsider your API design when that happens. Sometimes, however, part of an API is locked. I recently described such a situation, which prompted me to write test-specific Eq instances. In short, the Haskell data type Finch was not an Eq instance, so I added this test-specific data type to improve testability:

data FinchEq = FinchEq { feqID :: Int , feqHP :: Galapagos.HP , feqRoundsLeft :: Galapagos.Rounds , feqColour :: Galapagos.Colour , feqStrategyExp :: Exp } deriving (Eq, Show)

Later, I also introduced a second test-specific data structure, CellStateEq to address the equivalent problem that CellState isn't an Eq instance. This means that I have two representations of essentially the same kind of data. If I, much later, learn that I need to add, remove, or modify a field of, say, Finch, I would also need to edit FinchEq.

There's a clear edit-time coupling with constant value 2. When I edit one, I also need to edit the other. In big-O perspective, we could say that the specific value of 1 is 2, or 1~2, and so the edits required to maintain this part of the code base is of the order O(1).

Maintaining Fake objects #

Another interesting example is the one that originally elicited this chain of thought. In Greyscale-box test-driven development I showed an example of how using interactive white-box testing with Dynamically Generated Test Doubles (AKA Dynamic Mocks) leads to Fragile Tests. More on this later, but I also described how using Fake Objects and state-based testing doesn't have the same problem.

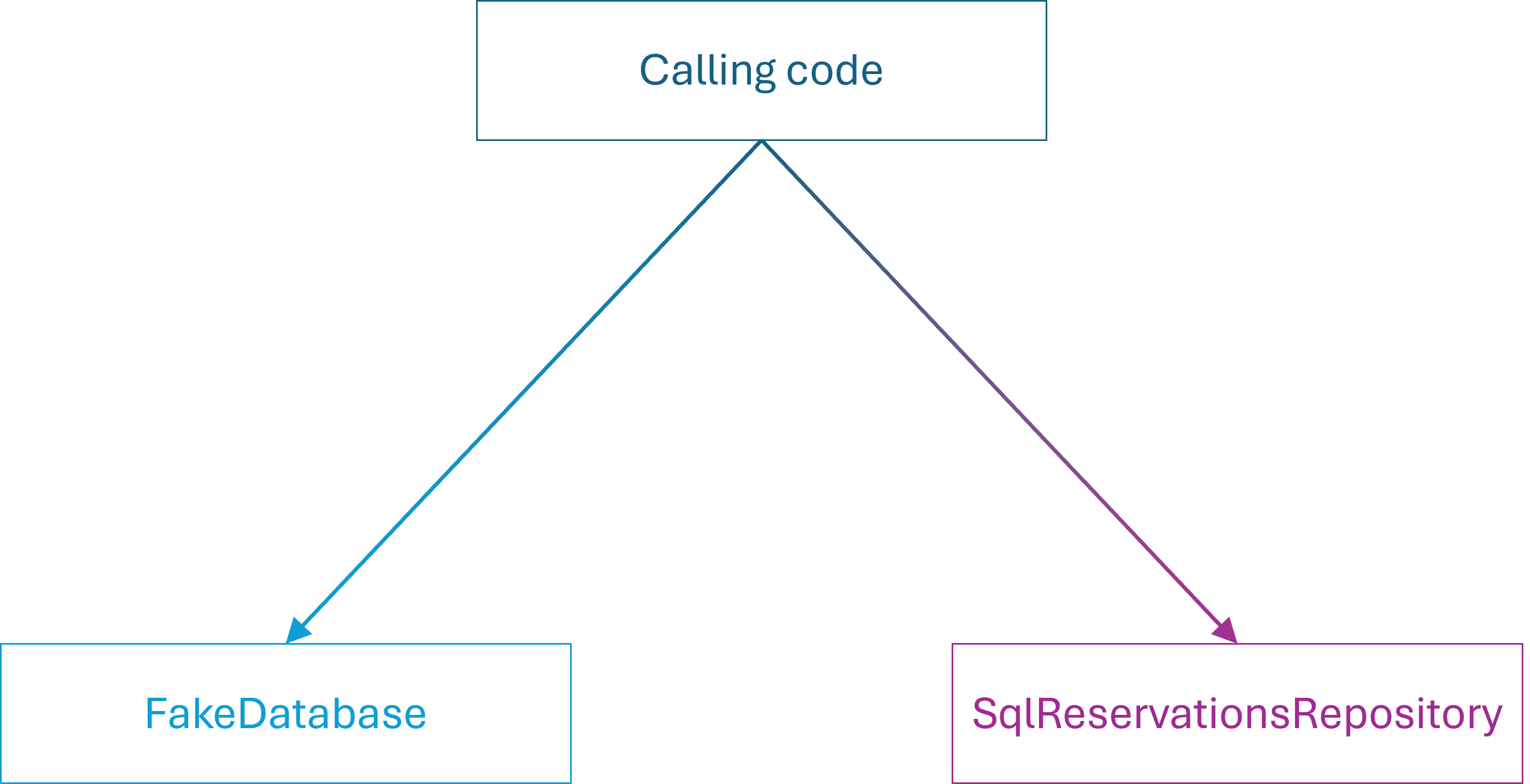

In a response on Bluesky Laszlo (@ladeak.net) pointed out that this seemed to imply a three-way coupling that I had, frankly, overlooked.

You can review the full description of the example in the article Greyscale-box test-driven development, but in summary it proceeds like this: We wish to modify an implementation detail related to how the system queries its database. Specifically, we wish to change an inclusive integer-based upper bound to an exclusive bound. Thus, we change the relevant part of the SQL WHERE clause from

@Min <= [At] AND [At] <= @Max"

to

@Min <= [At] AND [At] < @Max"

Specifically, the single-character edit removes = from the rightmost <=.

Since this modification changes the implied contract, we also need to edit the calling code. That's another single-line edit that changes

var max = min.AddDays(1).AddTicks(-1);

to

var max = min.AddDays(1);

What I had overlooked was that I should also have changed the single test-specific Fake object used for state-based testing. Since I changed the contract of the IReservationsRepository interface, and since Fakes are Test Doubles with contracts, it follows that the FakeDatabase class must also change.

This I had overlooked because no tests based on FakeDatabase failed. More on that in a future post, but the required edit is easy enough. Change

.Where(r => min <= r.At && r.At <= max).ToList());

to

.Where(r => min <= r.At && r.At < max).ToList());

Again, the edit involves deleting a single = character.

Still, in this example, not only two, but three files are coupled. With the perspective of big-O notation, however, we may say that 1~3, and the order of edits required to maintain this part of the code base remains O(1). Later in this article, I will discuss the maintenance burden of dynamic mocks, which I consider to be O(n). Thus, even if I have a three-way coupling, I don't expect the coupling to grow over time. That's the point: I prefer O(1) over O(n).

Large values of 1 #

As I'm sure practical programmers know, big-O notation has limitations. First, as Rob Pike observed, "n is usually small". More germane to this discussion

"algorithms have big constants."

In this context, this implies that the constant we're deliberately ignoring when we label something O(1) could, in theory, be significant. We don't write O(2,000,000), but if we did, it would look like more, wouldn't it? Even if it doesn't depend on n.

It looks to me that when we discuss source code edits, 5 or 6 could already be considered large.

Layers #

Although software design thought leaders have denounced layered software architecture more than a decade ago, I don't entirely agree with that position. That, however, is a topic for a different article. In any case, I still regularly see examples of design that involves a UI DTO, a Domain Model, and a Data Access layer.

As I enumerated in 2012, a simple operation, such as adding a label field, involves at least six steps.

- "A Label column must be added to the database schema and the DbTrack class.

- "A Label property must be added to the Track class.

- "The mapping from DbTrack to Track must be updated.

- "A Label property must be added to the TopTrackViewModel class.

- "The mapping from Track to TopTrackViewModel must be updated.

- "The UI must be updated."

People often complain about all the seemingly redundant work involved with such layering, and I don't blame them. At least, if there's no clear motivation for a design like that, and no evident benefit, it looks like redundant work. While you can make good use of separating concerns across layers, that's outside the scope of this article. In the naive way most often employed, it seems like mindless ceremony.

Even so, how would we denote the above enumeration in terms of big-O notation? Adding a label field is an O(1) edit.

How so? Adding, changing, or deleting a field in a particular database table always entails the same number of steps (six) as outlined above. If, in addition to the Track table you want to add, say, an Album table, you create it according to the three-layer model. This again means that every edit of that table involves six steps. It's still O(1), with 1~6, but already it hurts.

Apparently, six may be a 'large constant'.

Linear edits #

So far, we've exclusively examined multiple examples of O(1) edits. Some of them, particularly the layered-architecture example, may seem counterintuitive at first. If it requires editing six different 'blocks' of code to make a single change (not counting tests!) is still O(1), then does anything constitute O(n), or any other kind of relationship?

To be realistic, I don't think we're in an analytical regime that allows us fine distinctions like identifying any kind of code organization to be, say O(lg n) or O(n lg n). On the other hand, examples of O(n) abound.

Every time you run into the Shotgun Surgery anti-pattern, you are looking at O(n) edits. As a simple example, consider poorly-factored logging, as for example shown initially in Repeatable execution. In such situations, you have n classes that log. If you need to change how logging is done, you must change n classes.

More generally, the main (unstated) goal of the DRY principle is to turn O(n) edits into O(1) edits.

Every junior developer already knows this. Notwithstanding, there's a category of code where even senior programmers routinely forget this.

Linear test coupling #

When it comes to automated testing, many developers treat test code stepmotherly. The most common mistake is the misguided notion that copy-and-paste code is fine in test code. It's not. Duplicated test code means that when you make a change in the System Under Test, n tests break, and you will have to fix each one individually, a clear O(n) edit (where n is the number of tests).

A more subtle example of an O(n) test maintenance burden can be found in test code that uses dynamic mocks. When you use a configurable mock object, each test contains isolated configuration code related to that specific test.

Let's look at an example. Consider the Moq-based tests from An example of interaction-based testing in C#. One test contains this Assert phase:

readerTD .Setup(r => r.Lookup(user.Id.ToString())) .Returns(Result.Success<User, IUserLookupError>(user)); readerTD .Setup(r => r.Lookup(otherUser.Id.ToString())) .Returns(Result.Success<User, IUserLookupError>(otherUser));

Another test arranges the same two Test Doubles, but configures the second differently.

readerTD .Setup(r => r.Lookup(user.Id.ToString())) .Returns(Result.Success<User, IUserLookupError>(user)); readerTD .Setup(r => r.Lookup(otherUserId)) .Returns(Result.Error<User, IUserLookupError>( UserLookupError.InvalidId));

Yet more tests arrange the System Under Test (SUT) in other combinations. Refer to the article for the full example.

Such tests don't contain duplication per se, but each test is coupled to the SUT's dependencies. When you change one of the interfaces, you break O(n) tests, and you have to fix each one individually.

As suggested earlier in the article, this is the reason to favour Fake Objects. While an interface change may still break the tests, the effort to correct them is O(1) edits.

Two kinds of coupling #

The big-O perspective on coupling suggests that there are two kinds of coupling: O(1) coupling and O(n) coupling. We can find duplication in both categories.

In the O(1) case, duplication is somehow limited. It may be that you are following the rule of three. This allows two copies of a piece of code to exist. It may be that you've made a particular architectural decision, such as using Fake Objects for testing (triplication), or using layered architecture (sextuplication). In these cases, there's a fixed number of edits that you have to make, and in principle, you should know where to make them.

I tend to be less concerned about this kind of coupling because it's manageable. In many cases, you may be able to lean on the compiler to guide you through the task of making a change. In other cases, you could have a checklist. Consider the above example of layered architecture. A checklist would enumerate the six separate steps you need to perform. Once you've checked off all six, you're done.

It may be slow, tedious work, but it's generally safe, because you are unlikely to forget a spot.

The O(n) case is where real trouble lies. This is the case when you copy and paste a snippet of code every time you need it somewhere new. When, later, you discover that there's a bug in the original 'source', you need to find all the places it occurs. Typical copy-paste code is often slightly modified after paste, so a naive search-and-replace strategy is likely to miss some instances.

Of course, if you've copied a whole method, function, class, or module, you may still be able to find it by name, but if you've only copied an unnamed block of code, that will not work either.

Not all edits are equally difficult #

To be fair, we should acknowledge that not all edit are equally difficult. There are kinds of changes you can automate. Most modern code editors come with refactoring support. In the case of testing with dynamic mocks, for example, you can rename methods, rearrange parameter lists, or remove a parameter.

Even so, some edits are harder. Changing the return type of a method tends to break calling code in most high-ceremony languages. Likewise, changing a primitive parameter (an integer, a Boolean, a string) to a complex object is non-trivial, as is adding a parameter with no obvious good default value. This is when O(n) coupling hurts.

Limitations #

So far, we've considered O(1) and O(n) edits. Are there O(lg n) edits, O(n2), or even O(2n) edits?

I can't rule it out, and if the reader can furnish some convincing examples, I'd be keen to learn about them. To be honest, though, I'm not sure it's that helpful. One could perhaps construe an example where inheritance creates a quadratic growth of subclasses, because someone is trying to model two independent features in a single inheritance tree. This, however, is just bad design, and we don't need the big-O lens to tell us that.

Conclusion #

As a thought experiment, one may adopt big-O notation as a viewpoint on code organisation. This seems particularly valuable when distinguishing between benign and malignant duplication. Duplication usually entails coupling. For a 'code architect', one of the most important tasks is to reduce, or at least control, coupling.

Some coupling is of the order O(1). Hidden in this notation is a constant, which may indicate that a change can be made with a single edit, two edits, six edits, and so on. Even if the actual number is 'large', you can put tools in place to minimize risk: A simple checklist may be enough, or perhaps you can leverage a static type system.

Other coupling is of the order O(n). Here, a single change must be made in O(n) different places, where n tends to grow over time, and there's no clear way to systematically find and identify them all. This kind of coupling strikes me as more dangerous than O(1) coupling.

When I sometimes seem to have a cavalier attitude to duplication, it's likely because I've already subconsciously identified a particular duplication as of the order O(1).