ploeh blog danish software design

The TDD Apostate

I've been doing Test-Driven Development since 2003. I still do, I still love it, and I still expect to be doing it in the future. Over the years, I've repeatedly returned to the discussion of whether TDD should be regarded as Test-Driven Development or Test-Driven Design. For a long time I've been of the conviction that TDD is both of those. Not so any longer.

TDD is not a good design methodology.

Over the years I've written tons of code with TDD. I've written code where tests blindly drove the design, and I've written code where the design was the result of a long period of deliberation, and the tests were only the manifestations of already well-formed ideas.

I can safely say that the code where tests alone drove the design never turned out particularly well. Although it was testable and, after a fashion, ‘loosely coupled', it was still Spaghetti Code in the sense that it lacked overall consistency and good abstractions.

On the other hand, I'm immensely pleased with code like AutoFixture 2.0, which was mostly the result of hours of careful contemplation riding my bike to and from work. It was still written test-first, but the design was well thought out in advance.

This made me think: did I just fail (repeatedly) at Test-Driven Design, or is the overall concept a fallacy?

That's a pretty hard question to answer; what constitutes good design? In the following, let's assume that the SOLID principles is a pretty good indicator of good design. If so, does test-first drive us towards SOLID design?

TDD versus the Single Responsibility Principle #

Does TDD ensure the application of the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)? This question is easy to answer and the answer is a resounding NO! Nothing prevents us from test-driving a God Class. I've seen many examples, and I've been guilty of it myself.

Constructor Injection is a much better help because it makes SRP violations so painful.

The score so far: 0 points to TDD.

TDD versus the Open/Closed Principle #

Does TDD ensure that we follow the Open/Closed Principle (OCP)? This is a bit harder to answer. I've previously argued that Testability is just another name for OCP, so that would in itself imply that TDD drives OCP. However, the issue is more complex than that, because there are several different ways we can address the OCP:

- Inheritance

- Composition

According to Roy Osherove's book The Art of Unit Testing, the Extract and Override technique is a common unit testing trick. Personally, I rarely use it, but if used it will indirectly drive us a bit towards OCP via inheritance.

However, we all know that we should favor composition over inheritance, so does TDD drive us in that direction? As I alluded to previously, TDD does tend to drive us towards the use of Test Doubles, which we can view as one way to achieve OCP via composition.

However, another favorite composition technique of mine is to add functionality with a Decorator. This is only possible if the original type implements an interface that can be decorated. It's possible to write a test that forces a SUT to implement an interface, but TDD as a technique in itself does not drive us in that direction.

Grudgingly, however, I must admit that TDD still scores half a point against OCP, for a total score so far of ½ point.

TDD versus the Liskov Substitution Principle #

Does TDD drive us towards adhering to the Liskov Substitution Princple (LSP)? Perhaps, but probably not.

Black box testing can't protect us against the SUT attempting to downcast its dependencies, but at least it doesn't particularly pull us in that direction either. When it comes to the SUT's treatment of a dependency, TDD pulls in neither direction.

Can we test-drive interface implementations that inadvertently violate the LSP? Yes, easily. As I discussed in a previous post, the use of Header Interfaces pulls us towards LSP violations. The more members an interface has, the more likely are LSP violations.

TDD can definitely drive us towards Header Interfaces (although they tend to hurt in the long run). I've seen this happen numerous times, and I've been there myself. TDD doesn't properly encourage LSP adherence.

The score this round: 0 points for TDD, for a running total of ½ point.

TDD versus the Interface Segregation Principle #

Does TDD drive us towards the Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)? No. It's pretty easy to test-drive a SUT towards a Header Interface, just as we can test-drive towards a God Class.

Another 0 points for TDD. The score is still ½ point to TDD.

TDD versus the Dependency Inversion Principle #

Does TDD drive us towards the Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)? Yes, it does.

The whole drive towards Testability - the ability to replace dependencies with Test Doubles - drives us exactly in the same direction as the DIP.

Since we tend to mistake such mechanistic loose coupling with proper application design, this probably explains why we, for so long, have confused TDD with good design. However, although I view loose coupling as a prerequisite for good design, it is by no means enough.

For those that still keep score, TDD scores 1 point against DIP, for a total of 1½ points.

TDD does not ensure SOLID #

With 1½ out of 5 possible points I have stated my case. I am convinced that TDD itself does not drive us towards SOLID design. It's definitely possible to use test-first techniques to drive towards SOLID designs, but that will always be an extra effort that supplements TDD; it's not something that is inherently built into TDD.

Obviously you could argue that SOLID in itself is not the end-all, be-all of proper API design. I would agree. However, based on my experience with TDD, I think the conclusion holds. TDD does not drive us towards good design. It is not a design technique.

I still write code test-first because I find it more productive, but I make design decisions out of band. I'm a Test-Driven Design Apostate.

On Role Interfaces, the Reused Abstractions Principle and Service Locators

As a comment to my previous post about interfaces being no guarantee for abstractions, Danny asks some interesting questions. In particular, his questions relate to Udi Dahan's presentation Intentions & Interfaces: Making patterns concrete (also known as Making Roles Explicit). Danny writes:

it would seem that Udi recommends creating interfaces for each "role" the domain object plays and using a Service Locator to find the concrete implementation ... or in his case the concrete FetchingStrategy used to pull data back from his ORM. This sounds like his application would have many 1:1 abstractions.

Can this be true, or can we consolidate Role Interfaces with the Reused Abstractions Principle (RAP) - preferably without resorting to a Service Locator? Yes, of course we can.

In Udi Dahan's talks, we see various examples where he queries a Service Locator for a Role Interface. If the Service Locator returns an instance he uses it; otherwise, he falls back to some sort of default behavior. Here is my interpretation of Udi Dahan's slides:

public void Persist(Customer entity) { var validator = this.serviceLocator .Get<IValidator<Customer>>(); if (validator != null) { validator.Validate(entity); } // Save entity in actual store }

This is actually not very pretty object-oriented code, but I have Udi Dahan suspected of choosing this implementation to better communicate the essence of how to use Role Interfaces. However, a more proper implementation would have a default (or Null Object) implementation of the Role Interface, and then the special implementation.

If we assume that a NullValidator exists, we can require that the Service Locator can always serve up a proper instance of IValidator<Customer>. This enables us to simplify the Persist method to something like this:

public void Persist(Customer entity) { var validator = this.serviceLocator .Get<IValidator<Customer>>(); validator.Validate(entity); // Save entity in actual store }

Either the Service Locator returns a specialized CustomerValidator, or it returns the NullValidator. In any case, this assumption enables us to leverage the Liskov Substitution Principle and refactor the conditional logic to polymorphism.

In other words: every single time we discover the need to extract a Role Interface, we should end up with at least two implementations: the Null Object and the Special Case. Thus the RAP is satisfied.

As a last refactoring, we can also get rid of the Service Locator. Instead, we can use Constructor Injection to inject IValidator<Customer> directly into the Persistence class:

public class CustomerPersistence { private readonly IValidator<Customer> validator; public CustomerPersistence(IValidator<Customer> v) { if (v == null) { throw new ArgumentNullException("..."); } this.validator = v; } public void Persist(Customer entity) { this.validator.Validate(entity); // Save entity in actual store } }

Thus, the use of Role Interfaces in no way hinges on using a Service Locator, and everything is good again :)

Comments

However, I'm sure there's a good answer for this but wouldn't you run into the same issue when it came time to use the CustomerPersistence class? How would you instantiate CustomerPersistence with it's dependencies without relying on a service locator?

Thank you.

Towards better abstractions

In my previous post I discussed why the use of interfaces doesn't guarantee that we work against good abstractions. In this post I will look at some guidelines that might be helpful in defining better abstractions.

One important trait of a useful abstraction is that we can create many different implementations of it. This is the Reused Abstractions Principle (RAP). This is particularly important because composition and separation of concerns often result in such reuse. Every time we use Null Objects, Decorators or Composites, we reuse the same abstraction to compose an application from separate classes that all adhere to the Single Responsibility Principle. For example, Decorators are an excellent way to implement Cross-Cutting Concerns.

The RAP gives us a way to identify good abstractions after the fact, but doesn't say much about the traits that make up a good, composable interface.

On the other hand, I find that the composability of an interface is a pretty good indicator of its potential for reuse. While we can create Decorators from just about any interface, creating meaningful Null Objects or Composites are much harder. As we previously saw, bad abstractions often prevent us from implementing a meaningful Composite.

Being able to implement a meaningful Composite is a good indication of a sound interface.

This understanding is equivalent to the realization associated with the concept of Closure of Operations from Domain-Driven Design. As soon as we achieve this, a lot of very intuitive, almost arithmetic-like APIs tend to follow. It becomes much easier to compose various instances of the abstraction.

With Composite as an indicator of good abstractions, here are some guidelines that should enable us to define more useful interfaces.

ISP #

The more members an interface has, the more difficult it is to create a Composite of it. Thus, the Interface Segregation Principle is a good guide, as it points us towards small interfaces. By extrapolation, the best interface would be an interface with a single member.

That's a good start, but even such an interface could be problematic if it's a Leaky Abstraction or a Shallow Interface. Still, let us assume that we aim for such Role Interfaces and move on to see what other guidelines are available to us.

Commands #

Commands, and by extension any interface that consists of all void methods, are imminently composable. To implement a Null Object, just ignore the input and do nothing. To implement a Composite, just pass on the input to each contained instance.

A Command is the epitome of the Hollywood Principle because telling is the only thing you can do. There's no way to ask a Command about anything when the method returns void. Commands also guarantee the Law of Demeter, because there's no way you can ‘dot' across a void :)

If a Command takes one or more input parameters, they must all stay clear of Shallow Interfaces and Leaky Abstractions. If these conditions are satisfied, a Command tends to be a very good abstraction. However, sometimes we just need return values.

Closure of Operations #

We already briefly discussed Closure of Operations. In C# we can describe this concept as any method that fits this signature in some way:

T DoIt(T x);

An interface that returns the same type as the input type(s) exhibit Closure of Operations. There may be more than one input parameter as long as they are all of the same type.

The interesting thing about Closure of Operations is that any interface with that quality is easily implemented as a Null Object (just return the input). A sort of Composite is often also possible because we can pass the input to each instance in the Composite and use some sort of aggregation or selection algorithm to return a result.

Even if the return type doesn't easily lend itself towards aggregation, you can often implement a coalescing behavior with a Composite by returning the first non-null instance returned by the contained instances.

Interfaces that exhibits Closure of Operations tend to be good abstractions, but it's not always possible to design APIs like that.

Reduction of Input #

Sometimes we can keep some of the benefits from Closure of Operations even though a pure model isn't possible. Any method that returns a type that is a subset of the input types also tends to be composable.

One variation is something like this:

T1 DoIt(T1 x, T2 y, T3 z);

In this sort of interface, the return type is the same as the first parameter. When creating Null Objects or Composites, we can generally just do as we did with pure Closure of Operations and ignore the other parameters.

Another variation is a method like this:

T1 DoIt(Foo<T1, T2, T3> foo);

where Foo is defined like this:

public class Foo<T1, T2, T3> { public T1 X { get; set; } public T2 Y { get; set; } public T3 Z { get; set; } }

In this case we can still reduce the input to create the output by simply selecting and returning foo.X and ignoring the other properties.

Still, we may not always be able to define APIs such as these.

Composable return types #

Sometimes (perhaps even most of the times) we can't mold our APIs into any of the above shapes because we inherently need to map one type into another type:

T2 Map(T1 x);

To keep such a method composable, we must then make sure that the output type itself is composable. This would allow us to implement a Composite by wrapping each return value from the contained instances into a Composite of the return type.

Likewise, we could create a Null Object by returning another Null Object for the return type.

In theory, we could repeat this design process to create a big chain of composable types, as long as the last type terminates the chain by fitting into one of the above shapes. However, this can quickly become unwieldy, so we should go to great efforts to make those chains as short as possible.

It should be noted that every type that implements IEnumerable fits pretty well into this category. A Null Object is simply an empty sequence, and a Composite is simply a sequence with multiple items. Thus, interfaces that return enumerables tend to be good abstractions.

Conclusion #

There are many well-known variations of good interface design. The above guiding principles looks only at a small, interrelated set. In fact, we can regard both Commands and Closure of Operations as degenerate cases of Reduction of Input. We should strive to create interfaces that directly fit into one of these categories, and when that isn't possible, at least interfaces that return types that fit into those categories.

Keeping interfaces small and focused makes this possible in the first place.

P.S. (added 2019-01-28) See my retrospective article on the topic.

Comments

I was able to follow you perfectly until the section "Composable return types", however I'd like to clarify how letting go of closure of operations affects composability. Certainly, if the return type isn't composable, you are SOL. However, conforming to the three previous shapes mentioned is only a (generally) sufficent but NOT necessary condition for composability, is that correct? I ask because you follow with "as long as the last type terminates the chain by fitting into one of the above shapes", and not just "... by being composable" so it muddies the waters a bit.

My second question is about this chain itself - not clear on what it is. It's not inheritance and I thought about the chain formed formed by recursively called Composites in the parent Composite's tree structure, but then they wouldn't be conforming to the same interface.

Also when you said other well-known variations of good interface design, were you talking about minimalism, RAP, rule/intent interfaces and ISP? I'm not aware of much more.

Many thanks!

Orchun, thank you for writing. I intend to write a retrospective on this article, in the light of what I've subsequently figured out. I briefly discuss that connection in another article, but I've yet to make a formal treatment out of it. Shortly told, all the 'shapes' identified here form monoids, and the Composite design pattern itself forms a monoid.

Stay tuned for a more detailed treatment of each of the above 'shapes'.

Regarding good interface design, apart from minimalism, my primary concern is that an API does its utmost to communicate the invariants of the interaction; i.e. the pre- and postconditions involved. This is what Bertrand Meyer called design by contract, what I simply call encapsulation, and is related to what functional programmers refer to when they talk about being able to reason about the code.

Interfaces are not abstractions

One of the first sound bites from the beloved book Design Patterns is this:

Program to an interface, not an implementation

It would seem that a corollary is that we can measure the quality of our code on the number of interfaces; the more, the better. However, that's not how it feels in reality when you are trying to figure out whether to use an IFooFactory, IFooPolicy, IFooPolicyFactory or perhaps even an IFooFactoryFactory.

Do you extract interfaces from your classes to enable loose coupling? If so, you probably have a 1:1 relationship between your interfaces and the concrete classes that implement them. That's probably not a good sign, and violates the Reused Abstractions Principle (RAP). I've been guilty of this and didn't like the result.

Having only one implementation of a given interface is a code smell.

Programming to an interface does not guarantee that we are coding against an abstraction. Interfaces are not abstractions. Why not?

An interface is just a language construct. In essence, it's just a shape. It's like a power plug and socket. In Europe we use one kind, and the US uses another, but it's only by convention that we transmit 230V through European sockets and 110V through US sockets. Although plugs only fit in their respective sockets, nothing prevents us from sending 230V through a US plug/socket combination.

Krzysztof Cwalina already pointed this out in 2004: interfaces are not contracts. If they aren't even contracts, then how can they be abstractions?

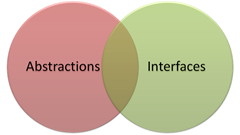

Interfaces can be used as abstractions, but using an interface is in itself no guarantee that we are dealing with an abstraction. Rather, we have the following relationship between interfaces and abstractions:

There are basically two sets: a set of abstractions and a set of interfaces. In the following we will discuss the set of interfaces that does not intersect the set of abstractions, saving the intersection for another blog post.

There are many ways an interface can turn out to be a poor abstraction. The following is an incomplete list:

LSP Violations #

Violating the Liskov Substitution Principle is a pretty obvious sign that the interface in use is a poor abstraction. This may be most obvious when the consumer of the interface needs to downcast an instance to properly work with it.

However, as Uncle Bob points out, even an interface as simple as this seemingly innocuous rectangle ‘abstraction' contains potential dangers:

public interface IRectangle { int Width { get; set; } int Height { get; set; } }

The issue becomes apparent when you attempt to let a Square class implement IRectangle. To protect the invariants of Square, you can't allow the Width and Height properties to differ. You have a couple of options, none of which are very good:

- Update both Width and Height to the same value when one of them are being written.

- Ignore the write operation when the caller attempts to assign an invalid value.

- Throw an exception when the caller attempts to assign a Width which is different from the Height (and vice versa).

From the point of view of a consumer of the IRectangle interface, all of these options would at the very least violate the Principle of Least Astonishment, and throwing exceptions would definitely cause the consumer to behave differently when consuming Square instances as opposed to ‘normal' rectangles.

The problem stems from the fact that the operations have side effects. Invoking one operation changes the state of a seemingly unrelated piece of data. The more members we have, the greater the risk is, so the Interface Segregation Principle can, to a certain extent, help.

Header Interfaces #

Since a higher number of members increases the risk of unexpected side effects and temporal coupling it should come as no surprise that interfaces mechanically extracted from all members of a concrete class are poor abstractions.

As always, Visual Studio makes it very easy to do the wrong thing by offering the Extract Interface refactoring feature.

We call such interfaces Header Interfaces because they resemble C++ header files. They tend to simply state the same thing twice without apparent benefit. This is particularly true when you have only a single implementation, which tends to be very likely for interfaces with many members.

Shallow Interfaces #

When you use the Extract Interface refactoring feature in Visual Studio, even if you don't extract every member, the resulting interface is shallow because it doesn't recursively extract interfaces from the concrete types exposed by the extracted members.

An example I've seen more than once involves extracting an interface from a LINQ to SQL or LINQ to Entities context in order to define a Repository interface. As an example, here's an interface extracted from a very simple LINQ to Entities context:

public interface IPostingContext { void AddToPostings(Posting posting); ObjectSet<Posting> Postings { get; } }

At first glance this may look useful, but it isn't. Even though it's an interface, it's still tightly coupled to a specific object context. Not only does ObjectSet<T> reference the Entity Framework, but the Posting class is defined by a very specific, auto-generated Entity context.

The interface may give you the impression of working against loosely coupled code, but you can't easily (if at all) implement a different IPostingContext with a radically different data access technology. You'll be stuck with this particular PostingContext.

If you must extract an interface, you'll need to do it recursively.

Leaky Abstractions #

Another way we can create problems for ourselves is when our interfaces leak implementation details. A good example can be found in the SystemWrapper project that provides extracted interfaces for various BCL types, such as System.IO.FileInfo. Those interfaces may enable mocking, but we shouldn't expect to ever be able to create another implementation of SystemWrapper.IO.IFileInfoWrap. In other words, those interfaces aren't very useful.

Another example is this attempt at defining a Repository interface:

public interface IFooRepository { string ConnectionString { get; set; } // ... }

Exposing a ConnectionString property strongly indicates that the repository is implemented on top of a database; this knowledge leaks through. If we wanted to implement the repository based on a web service, we might be able to repurpose the ConnectionString property to a service URL, but it would be a hack at best - and how would we define security settings in that scenario?

Exposing a FileName property on an interface that represents an abstract resource is another example of a Leaky Abstraction.

Leaky Abstractions like these are often difficult to reuse. As an example, it would be difficult to implement a Composite out of the above IFooRepository - how do you aggregate a ConnectionString?

Conclusion #

In short, using interfaces in no way guarantees that we operate with appropriate abstractions. Thus, the proliferation of interfaces that typically follow from TDD or use of DI may not be the pure goodness we tend to believe.

Creating good abstractions is difficult and requires skill. In a future post, I'll look at some principles that we can use as guides.

Comments

The reason why the Framework Design Guidelines favor abstract classes is related to keeping options open for future extensions to abstractions without breaking backwards compatibility. It makes tons of sense when you just have to respect backwards compatibility when adding new features. This is the case for big, commercial frameworks like the BCL. However, I'm beginning to suspect that this is kind of a pseudo-argument; it's really more an excuse for creating abstractions that don't adhere to the Open/Closed Principle.

On the other hand, it isn't that important if you control the entire code base in question. This is often the case for enterprise applications, where essentially you only have one customer and at most a handful of deployments.

The problem with base classes is that they are a much more heavy-handed approach. Because you can only derive from a single base class, it becomes impossible to implement more than one Role Interface in the same class. Because of that constraint, I tend to prefer interfaces over base classes.

The way I understand your post is not that you want me to change this, which is also impossible in a statically typed language.

Do I understand you correctly that you are more talking about how I design these dependencies so they would be - well better designed?

So in a way, if I understand you correctly, the things you are saying her could be applied in fx. Ruby as well, since they are design principles and not language stuff?

I've found this post to be quite an interesting read. At first, I was not in complete agreement, but as I took a step back and examined the way I write domain-driven code, I realized 99% of my code follows these concepts and rarely would I ever have a 1:1 relationship.

Today I happened upon a good video from one of Udi Dahan's talks: "Making Roles Explicit". It can be found here: http://www.infoq.com/presentations/Making-Roles-Explicit-Udi-Dahan

You can find some examples of his talk in practice here:

http://www.simonsegal.net/blog/2010/03/18/nfetchspec-code-entity-framework-repository-fetching-strategies-specifications-code-only-mapping-poco-and-making-roles-explicit/

If you happen to have some time to watch the speech, I was curious to hear your opinion on the subject as it seems like it would violate the concepts of this blog post. I still haven't wrapped my head around it all, but it would seem that Udi recommends creating interfaces for each "role" the domain object plays and using a Service Locator to find the concrete implementation ... or in his case the concrete FetchingStrategy used to pull data back from his ORM. This sounds like his application would have many 1:1 abstractions. I am familiar with your stance on the Service Locator and look forward to your book coming out. :)

Thanks,

Danny

Thanks for your comments. If you manage to read your way through my follow-up post you'll notice that I already discuss Role Interfaces there :)

I actually prefer Role Interfaces over Header Interfaces, but I can understand why you ask the questions you do. In fact, I went ahead and wrote a new blog post to answer them. HTH :)

I assume you'll use same constructor injection with abstract factory but how will you avoid 1:1 mapping in these cases? Using the same trick with NullService and WcfService?

What is a good abstraction for a Wcf service or for a CloudQueueClient?

Thanks in advance

public interface IChannel { void Send(object message); }

for sending messages, and this one to handle them:

public interface IMessageConsumer<T> { void Consume(T message); }

Since both are Commands (they return void) they compose excellently.

"If the only class that ever implements the Customer interface is CustomerImpl, you don't really have polymorphism and substitutability because there is nothing in practice to substitute at runtime. It's fake generality. All you have is indirection and code clutter, which just makes the code harder to understand."

From there I thought that 1:1 mapping means one implementation to one interface.

From your example it seems that 1:1 mapping referes to not having all members of an implementation matching exactly all members of the interface.

Which one is true?

Thanks again

What gave you that other impression?

But that's usually accomplished with decorators (we always need cross cutting concerns) and null objects, right?

With an interface like IChannel, a Composite also becomes possible, in the case that you would like to broadcast a message on multiple channels.

Thanks )

For a more complete application, see the Booking sample CQRS application. It uses Moq for Test Doubles, and I very consciously wrote that code base with the RAP in mind.

Do you have plans to publish some books about software development? Some kind of patterns explanation.. or best practices for .NET developers - with actual technologies? (not only DI =))

I think you can not only develop something but also explain how =)

Junlong, thank you for writing. This blog post already contains some links, of which I think that Reused Abstractions Principle (RAP) does the best job of describing the problem.

For what it's worth, I also discuss what makes a good abstraction in my book Code That Fits in Your Head.

Mark, I think abstraction is (and always has been) an overloaded term. And it hurts our profession, because important concpets become less clear.

Abstraction, in the words of Uncle Bob, is the [...] amplification of the essential and the elimination of the irrelevant."

Divindig a big method in smaller ones is the perfect example of that phrase: we amplify the essential (a call to a new method with a good name indicating what it does) while eliminating the irrelevant (hiding the code [how it does] behind a new method [abstraction]). If we want to know the hows, we navigate to that method implementation. What = essential / How = irrelevant.

This is completelly related to the concept of fractal architecture from your book, we just zoom in when we want. (Great book by the way, going to read it for the 3rd time).

I think we confuse the abstract (concept) with abstract (keyword, opposite of concrete) and interface (concept, aka API) with interface (keyword).

Interfaces (keyword) are always abstractions (concept), because they provide a list of methods/functions (API) for executing some logic that is abstracted (concept) behind it. The real questions are "are they good abstractions?", "Why are you using interfaces (keyword) for a single (1:1) implementation?"

Bottom line: interfaces (keyword) are always abstractions (concept), but not always good ones.

If you have the time, please write an article expanding on that line of reasoning.

Alex, thank you for writing. There are several overloaded og vague terms in programming: Client, service, unit test, mock, stub, encapsulation, API... People can't even agree on how to define object-oriented or functional programming.

I don't feel inclined to add to the confusion by adding my own definition to the mix.

As you've probably observed, I use Robert C. Martin's definition of abstraction in my book. According to that definition, you can easily define an interface that's not an abstraction: Just break the Dependency Inversion Principle. There are plenty of examples of those around: Interface methods that return or take as parameters ORM objects, or returning a database ID from a Create method. Such interfaces don't eliminate the irrelevant.

Mark, thanks for the response. There are two overloaded terms in programming that I consider the most important and the most misunderstood: abstraction and encapsulation.

Abstraction is important because it's about managing complexity, encapsulation is important because it's about preserving data integrity.

These are basic, fundamental (I can't stress this enough) concepts that enable the sustainable growth of a software project. I'm on the front-line here, and I know what a codebase that lacks these two concepts looks like. I think you do too. It ain't pretty.

Oddly enough, these aren't taught correctly at all! In my (short) formal training at a university, abstraction was taught in terms of abstract classes/inheritance (OOP). Encapsulation as nothing more than using getters and setters (use auto-properties and you're encapsulated. Yay!). There were no mentions of reducing complexity or preserving integrity whatsoever. I dropped out after two years. The only thing I learned from my time at the university is that there is an immense gap between the industry and educational institutions.

I'm mostly (if not completely) a self-taught programmer. I study a lot, and I'm always looking for new articles, books, etc. It took me ~7 years to find a coherent explanation of abstraction and encapsulation.

Initially, I asked myself "am I the only one who didn't have such basic knowledge, even though being a programmer for almost 10 years?" Then I started asking around work colleagues for definitions of those terms: turns out I wasn't the only one. I can't say I was surprised.

Maybe I am a fool for giving importance to such things as definitions and terminology of programming terms, but I can't see how we can move our profession towards a more engineering-focused one if we don't agree on (and teach correctly) basic concepts. Maybe I need Adam Barr's time machine.

Alex, thank you for writing. I agree with you, and I don't think that you're a fool for considering these concepts fundamental. Over a decade of consulting, I ran into the same fundamental mistakes over and over again, which then became the main driver for writing Code That Fits in Your Head.

It may be that university fails to teach these concepts adequately, but to be fair, if you consider that the main goal is to educate young people who may never have programmed before, maintainability may not be the first thing that you teach. After all, students should be able to walk before they can run.

Are there better ways to teach? Possibly. I'm still pursuing that ideal, but I don't know if I'll find those better ways.

Integrating AutoFixture with ObjectHydrator

Back in the days of AutoFixture 1.0 I occasionally got the feedback that although people liked the engine and its features, they didn't like the data it generated. I think they particularly didn't like all the Guids, but Håkon Forss suggested combining Object Hydrator's data generator with AutoFixture.

In fact, this suggestion made me realize that AutoFixture 1.0's engine wasn't extensible enough, which again prompted me to build AutoFixture 2.0. Now that AutoFixture 2.0 is out, what would be more fitting than to examine whether we can do what Håkon suggested?

It turns out to be pretty easy to customize AutoFixture to use Object Hydrator's data generator. The main part is creating a custom ISpecimenBuilder that acts as an Adapter of Object Hydrator:

public class HydratorAdapter : ISpecimenBuilder { private readonly IMap map; public HydratorAdapter(IMap map) { if (map == null) { throw new ArgumentNullException("map"); } this.map = map; } #region ISpecimenBuilder Members public object Create(object request, ISpecimenContext context) { var pi = request as PropertyInfo; if (pi == null) { return new NoSpecimen(request); } if ((!this.map.Match(pi)) || (this.map.Type != pi.PropertyType)) { return new NoSpecimen(request); } return this.map.Mapping(pi).Generate(); } #endregion }

The IMap interface is defined by Object Hydrator, ISpecimenBuilder and NoSpecimen are AutoFixture types and the rest are BCL types.

Each HydratorAdapter adapts a single IMap instance. The IMap interface only works with PropertyInfo instances, so the first thing to do is to examine the request to figure out whether it's a request for a PropertyInfo at all. If this is the case and the map matches the request, we ask it to generate a specimen for the property.

To get all of Object Hydrator's maps into AutoFixture, we can now define this customization:

public class ObjectHydratorCustomization : ICustomization { #region ICustomization Members public void Customize(IFixture fixture) { var builders = from m in new DefaultTypeMap() select new HydratorAdapter(m); fixture.Customizations.Add( new CompositeSpecimenBuilder(builders)); } #endregion }

The ObjectHydratorCustomization simply projects all maps from Object Hydrator's DefaultTypeMap into instances of HydratorAdapter and adds these as customizations to the fixture.

This enables us to use Object Hydrator with any Fixture instance like this:

var fixture = new Fixture() .Customize(new ObjectHydratorCustomization());

To prove that this works, here's a dump of a Customer type created in this way:

{

"Id": 1,

"FirstName": "Raymond",

"LastName": "Reeves",

"Company": "Carrys Candles",

"Description": "Lorem ipsum dolor sit",

"Locations": 53,

"IncorporatedOn": "\/Date(1376154940000+0200)\/",

"Revenue": 33.57,

"WorkAddress": {

"AddressLine1": "32373 BALL Lane",

"AddressLine2": "29857 DEER PARK Dr.",

"City": "fullerton",

"State": "NM",

"PostalCode": "27884",

"Country": "GI"

},

"HomeAddress": {

"AddressLine1": "66377 NORTH STAR Pl.",

"AddressLine2": "33406 MAY Dr.",

"City": "miami",

"State": "MD",

"PostalCode": "18361",

"Country": "PH"

},

"Addresses": [],

"HomePhone": "(388)538-1266",

"Type": 0

}

Without Object Hydrator's data generators, this would have looked like this instead:

{

"Id": 1,

"FirstName": "FirstNamebf53cb4c-3aae-4963-bb0c-ad0219293736",

"LastName": "LastName079f7ab2-d026-48c5-8cfb-76e0568d1d79",

"Company": "Company9ffe4640-2534-4ef7-b066-fb6bbe3a668c",

"Description": "Descriptionf5843974-b14b-4bce-b3cc-63ad6aaf3ab2",

"Locations": 2,

"IncorporatedOn": "\/Date(1290169587222+0100)\/",

"Revenue": 1.0,

"WorkAddress": {

"AddressLine1": "AddressLine1f4d50570-423e-4a74-8348-1c54402ffe48",

"AddressLine2": "AddressLine2031fe3e2-40c1-4ec3-b445-e88c213457e9",

"City": "Citycd33fce3-66bb-457d-8f99-98a16c0c5bf1",

"State": "State40bebd6d-6073-4421-8a74-e910ff9d09e3",

"PostalCode": "PostalCode1da93f22-799b-4f6b-a5ce-f4816f8bbb05",

"Country": "Countryfa2ad951-ce0c-42a4-ab55-c077b6e03f00"

},

"HomeAddress": {

"AddressLine1": "AddressLine145cbffeb-d7a9-4778-b297-d010c30b7614",

"AddressLine2": "AddressLine2e86d6476-5bdc-4940-a8ee-975bf3f65d49",

"City": "City6ae3aab9-7c73-4768-ae7d-a6ea515c816a",

"State": "State56de6222-fd84-46b0-ace0-c6098dbd0681",

"PostalCode": "PostalCodeca1af9af-a97b-4966-b156-cfbebd6d5e38",

"Country": "Country6960eebe-fe6f-4b63-ad73-7ba6a2b95791"

},

"Addresses": [],

"HomePhone": "HomePhone623f9d6f-febe-4c9f-87f8-e90d7e57eb46",

"Type": 0

}

One limitation of Object Hydrator is that it requires the classes to have default constructors. AutoFixture doesn't have that constraint, and to prove that I defined the only available Customer constructor like this:

public Customer(int id)

With AutoFixture, this is not a problem and the Customer instance is created as described above.

With the extensibility model of AutoFixture 2.0 I am pleased to be able to verify that Håkon Forss (and others) can now have the best of both worlds :)

Comments

public class ObjectHydratorCustomization :

ICustomization

{

#region ICustomization Members

public void Customize(IFixture fixture)

{

var builders= (from m in new DefaultTypeMap()

select new HydratorAdapter(m) as ISpecimenBuilder);

fixture.Customizations.Add(

new CompositeSpecimenBuilder(builders));

}

#endregion

}

Here it is.

As always feel free to use any part you'd like.'

Rhino Mocks-based auto-mocking with AutoFixture

AutoFixture now includes a Rhino Mocks-based auto-mocking feature similar to the Moq-based auto-mocking customization previously described.

The developer of this great optional feature, the talented but discreet Mikkel has this to say:

"The auto-mocking capabilities of AutoFixture now include auto-mocking using Rhino Mocks, completely along the same lines as the existing Moq-extension. Although it will not be a part of the .zip-distribution before the next official release, it can be built from the latest source code (November 13, 2010) which contains the relevant VS2008 solution: AutoRhinoMock.sln. It is built on Rhino.Mocks version 3.6.0.0. To use it, add a reference to Ploeh.AutoFixture.AutoRhinoMock.dll and customize the Fixture instance with:

var fixture = new Fixture() .Customize(new AutoRhinoMockCustomization());

"which automatically will result in mocked instances of requests for interfaces and abstract classes."

I'm really happy to see the AutoFixture eco-system grow in this way, as it both demonstrates how AutoFixture gives you great flexibility and enables you to work with the tools you prefer.

Refactoring from Abstract Factory to Decorator

Garth Kidd was so nice to point out to me that I hadn't needed stop where I did in my previous post, and he is, of course, correct. Taking a dependency on an Abstract Factory that doesn't take any contextual information (i.e. has no method parameters) is often an indication of a Leaky Abstraction. It indicates that the consumer has knowledge about the dependency's lifetime that it shouldn't have.

We can remove this flaw by introducing a Decorator of the IRepository<T> interface. Something like this should suffice:

public class FoundRepository<T> : IRepository<T> { private readonly IRepository<T> repository; public FoundRepository(IRepositoryFinder<T> finder) { if (finder == null) { throw new ArgumentNullException("finder"); } this.repository = finder.FindRepository(); } /* Implement IRepository<T> by delegating to * this.repository */ }

This means that we can change the implementation of MyServiceOperation to this:

public void MyServiceOperation( IRepository<Customer> repository) { // ... }

This is much better, but this requires a couple of notes.

First of all we should keep in mind that since FoundRepository creates and saves an instance of IRepository right away, we should control the lifetime of FoundRepository. In essense, the lifetime should be tied to the specific service operation. Two concurrent invocations of MyServiceOperation should each receive separate instances of FoundRepository.

Many DI containers support Factory methods, so it may not even be necessary to implement FoundRepository explicitly. Rather, it would be possible to register IRepository<T> so that an instance is always created by invoking IRepositoryFinder<T>.FindRepository().

Comments

I am asking, because I have a similar situation:

In the project I am currently refactoring, I created a lot of ConfiguredXYZ decorators that are modeled after this article.

They decorate classes, that have both dependencies and primitive types as ctor parameters. I use the decorator to read these primitive values from the configuration and to create an instance of the decorated class.

Example:

public ConfiguredCache(IConfigService configService, ISomeOtherDependency dep)

{

var expiryTime = configService.Get<DateTime>("ExpiryTimeForCache");

_configuredCache = new ExpiringCache(expiryTime, dep);

}

If IConfigService is implemented to read the database, I will hit the database in the constructor.

What do you think about it? Wouldn't it be better to create the instance of the ExpiringCache only when someone really needs it by invoking a method on ConfiguredCache?

You could also go the other way and perform a lazy evaluation of the dependency, but this is far more complicated to implement because it means that you'd be changing the state of the consumer. This again means that if you want to share the consumer as another dependency, you'll also need to think about thread safety.

In most cases I'd regard lazy evaluation as a premature optimization. As I have explained in another blog post, we shouldn't worry about the cost of composing an object graph.

In your example, IConfigService isn't really a dependency because the ConfiguredCache class doesn't depend on it - it only use it to get an instance of ExpiringCache. Change the constructor by removing the IConfigService and instead require an ExpiringCache (or the interface it implements). Some third party can take care of wiring up the IConfigService for you.

So what if it hits the database? It's probably going to do that sooner or later (meaning, typically, milliseconds or even seconds later) so does it matter? And will it happen often? A cache is only effective if it's shared, which means that we can share it with the Singleton lifetime. If we do that we only need to create the instance once per application, which again means that in the overall picture, that single database hit is insignificant.

Could you write a blog post about that refactoring step you would perform after you refactored to decorators?

I agree with your points in general, but they don't solve the problem that lead to those decorators in the first place:

The configuration of ExpiringCache is complex - not in the sample code, but in the real code. That was the whole reason for introducing those ConfiguredXYZ decorators, because I didn't want to have that complex configuration in the composition root. If you wouldn't create these decorators, how would you do it then? Create an ICache factory that returns a new ExpiringCache? This factory again would need IConfigService and ISomeOtherDependency to work, so from the constructor it would be the same as with the decorator...

And how would you register this factory with the container while reserving auto-wiring? Would you use Autofac's RegisterAdapter to register from ICacheFactory to ICache using the Create method of ICacheFactory?

If I would perform this complex configuration in the Composition Root, it would become a monstrosity, because it would mean to put the other configurations in there, too.

I like my Composition Root "to just work", so I work with conventions. Putting the configurations in there would make this impossible...

The code that reads configuration etc. needs to go somewhere. The Composition Root is the correct place because it makes the rest of your application code decoupled from your configuration source(s).

There's nothing that prevents you from expressing conventions around configuration settings as well.

But: the configuration code that currently is spread out in several classes would all be in the composition root. Note: "the configuration code" really consists of several classes that are not related to each other. One class configures the SAP object (which SAP server to use, username, password etc.), another configures the cache (see example above), yet another configures the Logger (which file to write to) etc.

It might well be a problem with the architecture per se, because I came to what I have now from an architecture that was centered around a service locator. All the lower levels now are very good, they get dependencies injected and work with them, but I can't figure out, where to put this configuration code.

Because, in my opinion, this configuration code is "domain code". What I mean with this is that it requires special knowledge about the domain it is used in. For example, I don't think that the composition root should need to know about details of an SAP connection, just to configure the SapConnection class... This is more than just reading configuration values and passing them to a constructor. In the SAP example, it reads some values from the database and based on these values it makes some decisions and only after that, the object is created.

Having written it like this, it really sounds as if I should use Abstract Factories, but you objected to them in one of your earlier answers, which confuses me :-)

Thus it follows that the Composition Root can be as large as necessary, but it must contain no logic. My personal rule of thumb is that all members must have a cyclomatic complexity of 1.

Configuration isn't logic, but you may have application logic that depends on configuration values, so the trick is to separate the logic from the source of the values. The logic goes elsewhere, but the values are being dehydrated (or otherwise initialized) by the Composition Root.

I would consider a SAP connection an infrastructure concern. If you base your domain logic on knowledge of infrastructure specifics you're making life hard for yourself.

Refactoring from Service Locator to Abstract Factory

One of the readers of my book recently asked me an interesting question that relates to the disadvantages of the Service Locator anti-pattern. I found both the question and the potential solution so interesting that I would like to share it.

In short, the reader's organization currently uses Service Locator in their code, but don't really see a way out of it. This post demonstrates how we can refactor from Service Locator to Abstract Factory. Here's the original question:

"We have been writing a WCF middle tier using DI

"Our application talks to multiple databases. There is one Global database which contains Enterprise records, and each Enterprise has the connection string of a corresponding Enterprise database.

"The trick is when we want to write a service which connects to an Enterprise database. The context for which enterprise we are dealing with is not available until one of the service methods is called, so what we do is this:

public void MyServiceOperation(

EnterpriseContext context)

{

/* Get a Customer repository operating

* in the given enterprise's context

* (database) */

var customerRepository =

context.FindRepository<Customer>(

context.EnterpriseId);

// ...

}"I'm not sure how, in this case, we can turn what we've got into a more pure DI system, since we have the dependency on the EnterpriseContext passed in to each service method. We are mocking and testing just fine, and seem reasonably well decoupled. Any ideas?"

When we look at the FindRepository method we quickly find that it's a Service Locator. There are many problems with Service Locator, but the general issue is that the generic argument can be one of an unbounded set of types.

The problem is that seen from the outside, the consuming type (MyService in the example) doesn't advertise its dependencies. In the example the dependency is a CustomerRepository, but you could later go into the implementation of MyServiceOperation and change the call to context.FindRepository<Qux>(context.EnterpriseId) and everything would still compile. However, at run-time, you'd likely get an exception.

It would be much safer to use an Abstract Factory, but how do we get there from here, and will it be better?

Let's see how we can do that. First, we'll have to make some assumptions on how EnterpriseContext works. In the following, I'll assume that it looks like this - warning: it's ugly, but that's the point, so don't give up reading just yet:

public class EnterpriseContext

{

private readonly int enterpriseId;

private readonly IDictionary<int, string>

connectionStrings;

public EnterpriseContext(int enterpriseId)

{

this.enterpriseId = enterpriseId;

this.connectionStrings =

new Dictionary<int, string>();

this.connectionStrings[1] = "Foo";

this.connectionStrings[2] = "Bar";

this.connectionStrings[3] = "Baz";

}

public virtual int EnterpriseId

{

get { return this.enterpriseId; }

}

public virtual IRepository<T> FindRepository<T>(

int enterpriseId)

{

if (typeof(T) == typeof(Customer))

{

return (IRepository<T>)this

.FindCustomerRepository(enterpriseId);

}

if (typeof(T) == typeof(Campaign))

{

return (IRepository<T>)this

.FindCampaignRepository(enterpriseId);

}

if (typeof(T) == typeof(Product))

{

return (IRepository<T>)this

.FindProductRepository(enterpriseId);

}

throw new InvalidOperationException("...");

}

private IRepository<Campaign>

FindCampaignRepository(int enterpriseId)

{

var cs = this.connectionStrings[enterpriseId];

return new CampaignRepository(cs);

}

private IRepository<Customer>

FindCustomerRepository(int enterpriseId)

{

var cs = this.connectionStrings[enterpriseId];

return new CustomerRepository(cs);

}

private IRepository<Product>

FindProductRepository(int enterpriseId)

{

var cs = this.connectionStrings[enterpriseId];

return new ProductRepository(cs);

}

}

That's pretty horrible, but that's exactly the point. Every time we need to add a new type of repository, we'll need to modify this class, so it's one big violation of the Open/Closed Principle.

I didn't implement EnterpriseContext with a DI Container on purpose. Yes: using a DI Container would make it appear less ugly, but it would only hide the design issue - not address it. I chose the above implementation to demonstrate just how ugly this sort of design really is.

So, let's start refactoring.

Step 1 #

We change each of the private finder methods to public methods.

In this example, there are only three methods, but I realize that in a real system there might be many more. However, we'll end up with only a single interface and its implementation, so don't despair just yet. It'll turn out just fine.

As a single example the FindCustomerRepository method is shown here:

public IRepository<Customer>

FindCustomerRepository(int enterpriseId)

{

var cs = this.connectionStrings[enterpriseId];

return new CustomerRepository(cs);

}

For each of the methods we extract an interface, like this:

public interface ICustomerRepositoryFinder

{

int EnterpriseId { get; }

IRepository<Customer> FindCustomerRepository(

int enterpriseId);

}

We also include the EnterpriseId property because we'll need it soon. This is just an intermediary artifact which is not going to survive until the end.

This is very reminiscent of the steps described by Udi Dahan in his excellent talk Intentions & Interfaces: Making patterns concrete. We make the roles of finding repositories explicit.

This leaves us with three distinct interfaces that EnterpriseContext can implement:

public class EnterpriseContext :

ICampaignRepositoryFinder,

ICustomerRepositoryFinder,

IProductRepositoryFinder

Until now, we haven't touched the service.

Step 2 #

We can now change the implementation of MyServiceOperation to explicitly require only the role that it needs:

public void MyServiceOperation(

ICustomerRepositoryFinder finder)

{

var customerRepository =

finder.FindCustomerRepository(

finder.EnterpriseId);

}

Since we now only consume the strongly typed role interfaces, we can now delete the original FindRepository<T> method from EnterpriseContext.

Step 3 #

At this point, we're actually already done, since ICustomerRepositoryFinder is an Abstract Factory, but we can make the API even better. When we consider the implementation of MyServiceOperation, it should quickly become clear that there's a sort of local Feature Envy in play. Why do we need to access finder.EnterpriseId to invoke finder.FindCustomerRepository? Shouldn't it rather be the finder's own responsibility to figure that out for us?

Instead, let us change the implementation so that the method does not need the enterpriseId parameter:

public IRepository<Customer> FindCustomerRepository()

{

var cs =

this.connectionStrings[this.EnterpriseId];

return new CustomerRepository(cs);

}

Notice that the EnterpriseId can be accessed just as well from the implementation of the method itself. This change requires us to also change the interface:

public interface ICustomerRepositoryFinder

{

IRepository<Customer> FindCustomerRepository();

}

Notice that we removed the EnterpriseId property, as well as the enterpriseId parameter. The fact that there's an enterprise ID in play is now an implementation detail.

MyServiceOperation now looks like this:

public void MyServiceOperation(

ICustomerRepositoryFinder finder)

{

var customerRepository =

finder.FindCustomerRepository();

}

This takes care of the Feature Envy smell, but still leaves us with a lot of very similarly looking interfaces: ICampaignRepositoryFinder, ICustomerRepositoryFinder and IProductRepositoryFinder.

Step 4 #

We can collapse all the very similar interfaces into a single generic interface:

public interface IRepositoryFinder<T>

{

IRepository<T> FindRepository();

}

With that, MyServiceOperation now becomes:

public void MyServiceOperation(

IRepositoryFinder<Customer> finder)

{

var customerRepository =

finder.FindRepository();

}

Now that we only have a single generic interface (which is still an Abstract Factory), we can seriously consider getting rid of all the very similarly looking implementations in EnterpriseContext and instead just create a single generic class. We now have a more explicit API that better communicates intent.

How is this better? What if a method needs both an IRepository<Customer> and an IRepository<Product>? We'll now have to pass two parameters instead of one.

Yes, but that's good because it explicitly calls to your attention exactly which collaborators are involved. With the original Service Locator, you might not notice the responsibility creep as you over time request more and more repositories from the EnterpriseContext. With Abstract Factories in play, violations of the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) becomes much more obvious.

Refactoring from Service Locator to Abstract Factories make it more painful to violate the SRP.

You can always make roles explicit to get rid of Service Locators. This is likely to result in a more explicit design where doing the right thing feels more natural than doing the wrong thing.

Pattern Recognition: Abstract Factory or Service Locator?

It's easy to confuse the Abstract Factory pattern with the Service Locator anti-pattern - particularly so when generics or contextual information is involved. However, it's really easy to distinguish between there two, and here's how!

Here are both (anti-)patterns in condensed form opposite each other:

| Abstract Factory | Service Locator |

public interface IFactory<T> |

public interface IServiceLocator |

For these examples I chose to demonstrate both as generic interfaces that take some kind of contextual information (context) as input.

In this example the context can be any object, but we could also have considered a more strongly typed context parameter. Other variations include more than one method parameter, or, in the degenerate case, no parameters at all.

Both interfaces have a simple Create method that returns the generic type T, so it's easy to confuse the two. However, even for generic types, it's easy to tell one from the other:

An Abstract Factory is a generic type, and the return type of the Create method is determined by the type of the factory itself. In other words, a constructed type can only return instances of a single type.

A Service Locator, on the other hand, is a non-generic interface with a generic method. The Create method of a single Service Locator can return instances of an infinite number of types.

Even simpler:

An Abstract Factory is a generic type with a non-generic Create method; a Service Locator is a non-generic type with a generic Create method.

The name of the method, the number of parameters, and other circumstances may vary. The types may not be generic, or may be base classes instead of interfaces, but at the heart of it, the question is whether you can ask for an arbitrary type from the service, or only a single, static type.

Comments

1) i've always viewed an IoC container (whether it's used for dependency injection or service location) as an amalgamation of design pattern, including the abstract factory (along with builders, registries, and others)

2) a design pattern is not always identified by implementation detail, but by intent. take a look at the Decorator and Proxy design patterns as implemented in C#, for example. There are, quite often and in the most basic of implementations, very few differences between these two patterns when it comes down to the implementation. the real difference is the intent of use

i don't think you are necessarily wrong in what you've said. i do think there's much more room for a gray area in between these two patterns, though. a service locator is an abstract factory (along with many other things), and an abstract factory can be used as a service locator. so, while the two patterns are distinct in their intent, they are often blurred and indistinguishable in implementation.

However, the whole point is that there are fundamental differences between Abstract Factory and Service Locator. One is good, the other is evil. Learning to tell them apart is important.

is it? looks to me like the Create method IS generic, it just so happens to have a constraint

Convention-based Customizations with AutoFixture

As previous posts have described, AutoFixture creates Anonymous Variables based on the notion of being able to always hit within a well-behaved Equivalence Class for a given type. This works well a lot of the time because AutoFixture has some sensible defaults: numbers are positive integers and strings are GUIDs.

This last part only works as long as strings are nothing but opaque blobs to the consuming class. This is, however, not an unreasonable assumption. Consider classes that implement Entities such as Person or Address. Strings will often take the form of FirstName, LastName, Street, etc. In all such cases, the value of the string usually doesn't matter.

However, there will always be cases where the value of a string has a special meaning of its own. It will often be best to let AutoFixture guide us towards a better API design, but this is not always possible. Sometimes there are rules that constrain the formatting of a string.

As an example, consider a Money class with this constructor:

public Money(decimal amount, string currencyCode)

{

if (currencyCode == null)

{

throw new ArgumentNullException("...");

}

if (!CurrencyCodes.IsValid(currencyCode))

{

throw new ArgumentException("...");

}

this.amount = amount;

this.currencyCode = currencyCode;

}

Notice that the constructor only allows properly formatted currency codes (such as e.g. “DKK”, “USD”, “AUD”, etc.) through, while other strings will throw an exception. AutoFixture's default behavior of creating GUIDs as strings is problematic, as the Money constructor will throw on a GUID.

We could attempt to fix this by changing the way AutoFixture generates strings in general, but that may not be the best solution as it may interfere with other string values. It is, however, easy to do:

fixture.Inject("DKK");

This simply injects the “DKK” string into the fixture, causing all subsequent strings to have the same value. However, a hypothetical Pizza class with Name and Description properties in addition to a Price property of type Money will now look like this:

{

"Name": "DKK",

"Price": {

"Amount": 1.0,

"CurrencyCode": "DKK"

},

"Description": "DKK"

}

What we really want is to customize only the currency code. This is where the extremely customizable architecture of AutoFixture can help us. As the documentation explains, lots of different request will flow through the kernel's Chain of Responsibility to create a Money instance. To populate the two parameters of the Money constructor, two ParameterInfo requests will be issued - one for each parameter. We can take advantage of this to create a custom ISpecimenBuilder that only addresses string parameters with the name currencyCode.

public class CurrencyCodeSpecimenBuilder :

ISpecimenBuilder

{

public object Create(object request,

ISpecimenContext context)

{

var pi = request as ParameterInfo;

if (pi == null)

{

return new NoSpecimen(request);

}

if (pi.ParameterType != typeof(string)

|| pi.Name != "currencyCode")

{

return new NoSpecimen(request);

}

return "DKK";

}

}

It simply examines the request to determine whether this is something that it should address at all. Only if the request is a ParameterInfo representing a string parameter named currencyCode do we deal with it. In any other case we return NoSpecimen, which simply tells AutoFixture that it should ask another ISpecimenBuilder instead.

Here we just return the hard-coded string “DKK”, but we could easily have expanded the example to use a more varied generation algorithm. I will leave that, as well as how to generalize this in other ways, as exercises to the reader.

With CurrencyCodeSpecimenBuilder available, we can add it to the Fixture like this:

fixture.Customizations.Add(

new CurrencyCodeSpecimenBuilder());

With this customization added, a Pizza instance now looks like this:

{

"Name": "namec6b7a923-ea78-4817-9e24-a6863a597645",

"Price": {

"Amount": 1.0,

"CurrencyCode": "DKK"

},

"Description": "Description63ef17d7-876d-46d8-af73-1ed91f83e699"

}

Notice how only the currency code is affected while all other string values are created by the default algorithm.

In a nutshell, a custom ISpecimenBuilder can be used to implement all sorts of custom conventions for AutoFixture. The one shown here applies the string “DKK” to all string parameters named currencyCode. This mean that the convention isn't necessarily constrained to the Money constructor, but applies to all ParamterInfo instances that fit the specification.

Comments

Thanks

The reason why the CurrencyCodeSpecimenBuilder is looking for a ParameterInfo instance is because the thing it's looking for is exactly the constructor parameter to the Money class.

If you instead want to match on a property, PropertyInfo is indeed the correct request to look for.

(and FieldInfo is used if you want to match on a public field...)

A request can be anything, but will often by a Type, ParameterInfo, or PropertyInfo.

You can use the context argument passed to the Create method to resolve other values; you only need to watch out for infinite recursions: you can't ask for an unconditional string if the Specimen Builder you're writing handles unconditional strings.

I've written several custom ISpecimenBuilder implementations similar to your example above, and I always wince when testing for the ParameterType.Name value (i.e., if(pi.Name == "myParamName"){...}). It seems like it makes a test that would use this implementation very brittle - no longer would I have freedom to change the name of the paramter to suit my asthetics, without relying on a refactoring tool (cough, cough, Resharper, cough, cough) to hopefully pickup on the string value in my test suite and prompt me to change it there as well.

This makes me think that I shouldn't need to be doing this, and that a design refactoring of my SUT would be a better option. Care to comment on this observation? Is there a common scenario/design trap that illustrates a better way? Or am I already in dangerous design territory based on my need to create an ISpecimenBuilder in the first place?

Jeff, thank you for writing. Your question warranted a new blog post; it may not answer all of your concerns, but hopefully some of them. Read it and let me know if you still have questions.

Comments

I think some of TDD's primary benefits are:

- it raises the quality of your features (less bugs, simpler, more thought out)

- it helps support you as you refactor to improve your design

- it helps people work on existing code

Thanks for the post, very thought provoking!

Kevin

I'd give at least half a point for helping with SRP, and probably a full point. Nevertheless, I'd agree with your larger idea that TDD isn't a license to turn your brain off. The TDD system is read-green-REFACTOR, and the refactor part means you need to engage your brain and apply design princples that will make your code stronger. The tests allow you to do that refactoring in relative safety.

The Design part of TDD is, imho all about designing your low level APIs. And they are designed for ease of use automatically because when you are writing your tests, you think, "What's the easiest way to invoke the functionality I'm contemplating?" As you have pointed out, ease of use is only one component of good design, so TDD doesn't design the code for you ALL BY ITSELF.

Knowing the limitations of the methodology you are employing is critical to getting the most out of it. While you can ride your bicycle to New York, there are few situations where that is the most practical way of getting there.

-Kelly

http://cleancoder.posterous.com/the-transformation-priority-premise

What I'm discussing here is whether or not you can use tests to blindly design APIs. That's a different perspective.

Are there authoritative sources that assert that you can? Or non-authoritative ones? If so, could you cite them, which would help to put the piece into context. Otherwise, I'm just hearing "red-green on its own doesn't produce good design", which I thought was pretty much obvious, given that the "refactor" step is where I've always expected the design part to happen, and the article boils down to "doing it wrong doesn't work".

;-)

TDD /drives/ through priority and constraint. Good tests fix intent, not implementation, while only allowing implementations to emerge that meet the intent. By definition then, it should not be coupled to elements of construction (or design as you are calling it).

I appreciate the point that you're making i.e. TDD != a SOLID design, but then I don't think it ever aspired to - that's why there was the "refactor" bit after getting your tests green.

In short, in order to be good at design, learn to design. Then TDD will help you get to a good design faster.

At the same time there I think it is clear that TDD can also drive the design of your class/program. But there is a quite big difference into turning that original "can" into a "should" or a "must". And I don't know why there is so many people obssesed in change the original intention of TDD.

Isaac for example in one of the commens makes a great point about refactoring and its impact of TDD. And that's the point of that "can". But this doesn't mean that you should only rely on TDD to design your project. To me is a great technique that helps 1. to force your team to make tests, 2. to force your team to think on the stuff they are solving and 3. to pop up design flaws that we never thought of.

"I’ve written code where tests blindly drove the design..."

I don't think this is true because it's not possible. Tests can't "blindly" drive any design, especially considering the fact that tests don't write themselves. It takes a human being, a programmer with ideas and plans for the software, to decide what tests to write and how to implement them.

Now, there is a context in which a phrase like "blindly drive" is valid, and it's the TDD method. No matter how great or valid your ideas for your software might be, TDD demands that you prove the worth of your ideas one tiny step at a time. You write a simple test, then you implement it in the most simple manner. Then you repeat, then you repeat, and eventually you're left with software that may or may not match with what you had in your head.

The method is "blind" to your ideas in that your implementation is focused on one tiny requirement, but it can't be blind to your ideas completely. What gave you the idea to write the test in the first place?

When programmers start TDD for the first time, their software doesn't magically become pure examples of the SOLID principles. It takes a lot of practice to know what tests/questions to write, where to start the TDD practice, and how generally to keep things together. And even with lots of experience, it's still possible to mess things up. If I mess up during my practice of TDD, it's not fair to blame the practice of TDD any more than it's fair to blame an automobile manufacturer if someone drives their car off the road.

I think that's kinda what you're doing when you say things like:

"Nothing prevents us from test-driving a God Class."

Nothing prevents us from test-driving a God class? How about the fact that the tests will be hard to write, be unmaintainable, and will generally smell? Whenever a class takes on additional responsibilities, the tests for those responsibilities have to be "mixed" with the other tests. That fact that the programmer is going test-first will provide him with the earliest clue that the class is taking on too much, will cause him to *design* a way around the SRP violation by using a separate class.

If TDD helps to provide so much evidence that a SRP violation is occurring, why go after it because it doesn't *force* the programmer to act based on that evidence?

Making up a series of TDD "versus" the SOLID principles seems a little far-fetched to me. TDD isn't meant to be a replacement for the human brain.

I agree with many of the things you say in your post. Thank you for inspiring such fruitful conversations.