ploeh blog danish software design

Some design patterns as universal abstractions

Some design patterns can be formalised by fundamental abstractions.

This article series submits results based on the work presented in an even larger series of articles about the relationship between design patterns and category theory.

Wouldn't it be wonderful if you could assemble software from predefined building blocks? This idea is old, and has been the driving force behind object-oriented programming (OOP). In Douglas Coupland's 1995 novel Microserfs, the characters attempt to reach that goal through a project called Oop!. Lego bricks play a role as a metaphor as well.

Decades later, it doesn't look like we're much nearer that goal than before, but I believe that we'd made at least two (rectifiable) mistakes along the way:

- Granularity

- Object-orientation

Granularity #

Over the years, I've seen several attempts at reducing software development to a matter of putting things together. These attempts have invariably failed.

I believe that one of the reasons for failure is that such projects tend to aim at coarse-grained building blocks. As I explain in the Interface Segregation Principle module of my Encapsulation and SOLID Pluralsight course, granularity is a crucial determinant for your ability to create. The coarser-grained the building blocks, the harder it is to create something useful.

Most attempts at software-as-building-blocks have used big, specialised building blocks aimed at non-technical users ("Look! Create an entire web site without writing a single line of code!"). That's just like Duplo. You can create exactly what the blocks were designed for, but as soon as you try to create something new and original, you can't.

Object-orientation #

OOP is another attempt at software-as-building-blocks. In .NET (the OOP framework with which I'm most familiar) the Base Class Library (BCL) is enormous. Many of the reusable objects in the BCL are fine-grained, so at least it's often possible to put them together to create something useful. The problem with an object-oriented library like the .NET BCL, however, is that all the objects are special.

The vision was always that software 'components' would be able to 'click' together, just like Lego bricks. The BCL isn't like that. Typically, objects have nothing in common apart from the useless System.Object base class. There's no system. In order to learn how the BCL works, you have to learn the ins and outs of every single class.

Better know a framework.

It doesn't help that OOP was never formally defined. Every time you see or hear a discussion about what 'real' object-orientation is, you can be sure that sooner or later, someone will say: "...but that's not what Alan Kay had in mind."

What Alan Kay had in mind is still unclear to me, but it seems safe to say that it wasn't what we have now (C++, Java, C#).

Building blocks from category theory #

While we (me included) have been on an a thirty-odd year long detour around object-orientation, I don't think all is lost. I still believe that a Lego-brick-like system exists for software development, but I think that it's a system that we have to discover instead of invent.

As I already covered in the introductory article, category theory does, in fact, discuss 'objects'. It's not the same type of object that you know from C# or Java, but some of them do consist of data and behaviour - monoids, for example, or functors. Such object are more like types than objects in the OOP sense.

Another, more crucial, difference to object-oriented programming is that these objects are lawful. An object is only a monoid if it obeys the monoid laws. An object is only a functor if it obeys the functor laws.

Such objects are still fine-grained building blocks, but they fit into a system. You don't have to learn tens of thousands of specific objects in order to get to know a framework. You need to understand the system. You need to understand monoids, functors, applicatives, and a few other universal abstractions (yes: monads too).

Many of these universal abstractions were almost discovered by the Gang of Four twenty years ago, but they weren't quite in place then. Much of that has to do with the fact that functional programming didn't seem like a realistic alternative back then, because of hardware limitations. This has all changed to the better.

Specific patterns #

In the introductory article about the relationship between design patterns and category theory, you learned that some design patterns significantly overlap concepts from category theory. In this article series, we'll explore the relationships between some of the classic patterns and category theory. I'm not sure that all the patterns from Design Patterns can be reinterpreted as universal abstractions, but the following subset seems promising:

- Composite as a monoid

- Null Object as identity

- Builder as a monoid

- Visitor as a sum type

- Chain of Responsibility as catamorphisms

- The State pattern and the State monad

- Postel's law as a profunctor

- The Liskov Substitution Principle as a profunctor

- Backwards compatibility as a profunctor

Summary #

Some design patterns closely resemble categorical objects. This article provides an overview, whereas the next articles in the series will dive into specifics.

Next: Composite as a monoid.

Inheritance-composition isomorphism

Reuse via inheritance is isomorphic to composition.

This article is part of a series of articles about software design isomorphisms.

Chapter 1 of Design Patterns admonishes:

Favor object composition over class inheritancePeople sometimes struggle with this, because they use inheritance as a means to achieve reuse. That's not necessary, because you can use object composition instead.

In the previous article, you learned that an abstract class can be refactored to a concrete class with injected dependencies.

Did you notice that there was an edge case that I didn't cover?

I didn't cover it because I think it deserves its own article. The case is when you want to reuse a base class' functionality in a derived class. How do you do that with Dependency Injection?

Calling base #

Imagine a virtual method:

public virtual OutVirt1 Virt1(InVirt1 arg)

In C#, a method is virtual when explicitly marked with the virtual keyword, whereas this is the default in Java. When you override a virtual method in a derived class, you can still invoke the parent class' implementation:

public override OutVirt1 Virt1(InVirt1 arg) { // Do stuff with this and arg var baseResult = base.Virt1(arg); // return an OutVirt1 value }

When you override a virtual method, you can use the base keyword to invoke the parent implementation of the method that you're overriding. The enables you to reuse the base implementation, while at the same time adding new functionality.

Virtual method as interface #

If you perform the refactoring to Dependency Injection shown in the previous article, you now have an interface:

public interface IVirt1 { OutVirt1 Virt1(InVirt1 arg); }

as well as a default implementation. In the previous article, I showed an example where a single class implements several 'virtual member interfaces'. In order to make this particular example clearer, however, here you instead see a variation where the default implementation of IVirt1 is in a class that only implements that interface:

public class DefaultVirt1 : IVirt1 { public OutVirt1 Virt1(InVirt1 arg) { // Do stuff with this and arg; return an OutVirt1 value. } }

DefaultVirt1.Virt1 corresponds to the original virtual method on the abstract class. How can you 'override' this default implementation, while still make use of it?

From base to composition #

You have a default implementation, and instead of replacing all of it, you want to somehow enhance it, but still use the 'base' implementation. Instead of inheritance, you can use composition:

public class OverridingVirt1 : IVirt1 { private readonly IVirt1 @base = new DefaultVirt1(); public OutVirt1 Virt1(InVirt1 arg) { // Do stuff with this and arg var baseResult = @base.Virt1(arg); // return an OutVirt1 value } }

In order to drive home the similarity, I named the class field @base. I couldn't use base as a name, because that's a keyword in C#, but you can use the prefix @ in order to use a keyword as a legal C# name. Notice that the body of OverridingVirt1.Virt1 is almost identical to the above, inheritance-based overriding method.

As a variation, you can inject @base via the constructor of OverridingVirt1, in which case you have a Decorator.

Isomorphism #

If you already have an interface with a 'default implementation', and you want to reuse the default implementation, then you can use object composition as shown above. At its core, it's reminiscent of the Decorator design pattern, but instead of receiving the inner object via its constructor, it creates the object itself. You can, however, also use a Decorator in order to achieve the same effect. This will make your code more flexible, but possibly also more error-prone, because you no longer have any guarantee what the 'base' is. This is where the Liskov Substitution Principle becomes important, but that's a digression.

If you're using the previous abstract class isomorphism to refactor to Dependency Injection, you can refactor any use of base to object composition as shown here.

This is a special case of Replace Inheritance with Delegation from Refactoring, which also describes the inverse refactoring Replace Delegation with Inheritance, thereby making these two refactorings an isomorphism.

Summary #

This article focuses on a particular issue that you may run into if you try to avoid the use of abstract classes. Many programmers use inheritance in order to achieve reuse, but this is in no way necessary. Favour composition over inheritance.

Next: Tester-Doer isomorphisms.

Abstract class isomorphism

Abstract classes are isomorphic to Dependency Injection.

This article is part of a series of articles about software design isomorphisms.

The introduction to Design Patterns states:

Program to an interface, not an implementation.When I originally read that, I took it quite literally, so I wrote all my C# code using interfaces instead of abstract classes. There are several reasons why, in general, that turns out to be a good idea, but that's not the point of this article. It turns out that it doesn't really matter.

If you have an abstract class, you can refactor to an object model composed from interfaces without loss of information. You can also refactor back to an abstract class. These two refactorings are each others' inverses, so together, they form an isomorphism.

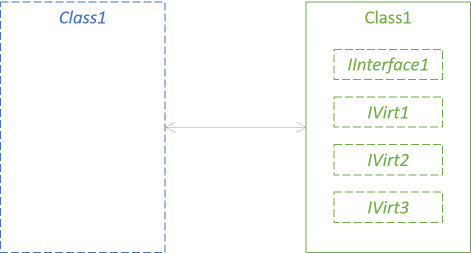

When refactoring an abstract class, you extract all its pure virtual members to an interface, each of its virtual members to other interfaces, and inject them into a concrete class. The inverse refactoring involves going back to an abstract class.

This is an important result, because upon closer inspection, the Gang of Four didn't have C# or Java interfaces in mind. The book pre-dates both Java and C#, and its examples are mostly in C++. Many of the examples involve abstract classes, but more than ten years of experience has taught me that I can always write a variant that uses C# interfaces. That is, I believe, not a coincidence.

Abstract class #

An abstract class in C# has this general shape:

public abstract class Class1 { public Data1 Data { get; set; } public abstract OutPureVirt1 PureVirt1(InPureVirt1 arg); public abstract OutPureVirt2 PureVirt2(InPureVirt2 arg); public abstract OutPureVirt3 PureVirt3(InPureVirt3 arg); // More pure virtual members... public virtual OutVirt1 Virt1(InVirt1 arg) { // Do stuff with this, Data, and arg; return an OutVirt1 value. } public virtual OutVirt2 Virt2(InVirt2 arg) { // Do stuff with this, Data, and arg; return an OutVirt2 value. } public virtual OutVirt3 Virt3(InVirt3 arg) { // Do stuff with this, Data, and arg; return an OutVirt3 value. } // More virtual members... public OutConc1 Op1(InConc1 arg) { // Do stuff with this, Data, and arg; return an OutConc1 value. } public OutConc2 Op2(InConc2 arg) { // Do stuff with this, Data, and arg; return an OutConc2 value. } public OutConc3 Op3(InConc3 arg) { // Do stuff with this, Data, and arg; return an OutConc3 value. } // More concrete members... }

Like in the previous article, I've deliberately kept the naming abstract (but added a more concrete example towards the end). The purpose of this article series is to look at the shape of code, instead of what it does, or why. From argument list isomorphisms we know that we can represent any method as taking a single input value, and returning a single output value.

An abstract class can have non-virtual members. In C#, this is the default, whereas in Java, you'd explicitly have to use the final keyword. In the above generalised representation, I've named these non-virtual members Op1, Op2, and so on.

An abstract class can also have virtual members. In C#, you must explicitly use the virtual keyword in order to mark a method as overridable, whereas this is the default for Java. In the above representation, I've called these methods Virt1, Virt2, etcetera.

Some virtual members are pure virtual members. These are members without an implementation. Any concrete (that is: non-abstract) class inheriting from an abstract class must provide an implementation for such members. In both C# and Java, you must declare such members using the abstract keyword. In the above representation, I've called these methods PureVirt1, PureVirt2, and so on.

Finally, an abstract class can contain data, which you can represent as a single data object, here of the type Data1.

The concrete and virtual members could, conceivably, call other members in the class - both concrete, virtual, and pure virtual. In fact, this is how many of the design patterns in the book work, for example Strategy, Template Method, and Builder.

From abstract class to Dependency Injection #

Apart from its Data, an abstract class contains three types of members:

- Those that must be implemented by derived classes: pure virtual members

- Those that optionally can be overriden by derived classes: virtual members

- Those that cannot be overridden by derived classes: concrete, sealed, or final, members

- Extract an interface from the pure virtual members.

- Extract an interface from each of the virtual members.

- Implement each of the 'virtual member interfaces' with the implementation from the virtual member.

- Add a constructor to the abstract class that takes all these new interfaces as arguments. Save the arguments as class fields.

- Change all code in the abstract class to talk to the injected interfaces instead of direct class members.

- Remove the virtual and pure virtual members from the class, or make them non-virtual. If you keep them around, their implementation should be one line of code, delegating to the corresponding interface.

- Change the class to a concrete (non-abstract) class.

public sealed class Class1 { private readonly IInterface1 pureVirts; private readonly IVirt1 virt1; private readonly IVirt2 virt2; private readonly IVirt3 virt3; // More virt fields... public Data1 Data { get; set; } public Class1( IInterface1 pureVirts, IVirt1 virt1, IVirt2 virt2, IVirt3 virt3 /* More virt arguments... */) { this.pureVirts = pureVirts; this.virt1 = virt1; this.virt2 = virt2; this.virt3 = virt3; // More field assignments } public OutConc1 Op1(InConc1 arg) { // Do stuff with this, Data, and arg; return an OutConc1 value. } public OutConc2 Op2(InConc2 arg) { // Do stuff with this, Data, and arg; return an OutConc2 value. } public OutConc3 Op3(InConc3 arg) { // Do stuff with this, Data, and arg; return an OutConc3 value. } // More concrete members... }

While not strictly necessary, I've marked the class sealed (final in Java) in order to drive home the point that this is no longer an abstract class.

This is an example of the Constructor Injection design pattern. (This is not a Gang of Four pattern; you can find a description in my book about Dependency Injection.)

Since it's optional to override virtual members, any class originally inheriting from an abstract class can choose to override only one, or two, of the virtual members, while leaving other virtual members with their default implementations. In order to support such piecemeal redefinition, you can extract each virtual member to a separate interface, like this:

public interface IVirt1 { OutVirt1 Virt1(InVirt1 arg); }

Notice that each of these 'virtual interfaces' are injected into Class1 as a separate argument. This enables you to pass your own implementation of exactly those you wish to change, while you can pass in the default implementation for the rest. The default implementations are the original code from the virtual members, but moved to a class that implements the interfaces:

public class DefaultVirt : IVirt1, IVirt2, IVirt3

When inheriting from the original abstract class, however, you must implement all the pure virtual members, so you can extract a single interface from all the pure virtual members:

public interface IInterface1 { OutPureVirt1 PureVirt1(InPureVirt1 arg); OutPureVirt2 PureVirt2(InPureVirt2 arg); OutPureVirt3 PureVirt3(InPureVirt3 arg); // More pure virtual members... }

This forces anyone who wants to use the refactored (sealed) Class1 to provide an implementation of all of those members. There's an edge case where you inherit from the original Class1 in order to create a new abstract class, and implement only one or two of the pure virtual members. If you want to support that edge case, you can define an interface for each pure virtual member, instead of one big interface, similar to IVirt1, IVirt2, and so on.

From Dependency Injection to abstract class #

I hope it's clear how to perform the inverse refactoring. Assume that the above sealed Class1 is the starting point:

- Mark

Class1asabstract. - For each of the members of

IInterface1, add a pure virtual member. - For each of the members of

IVirt1,IVirt2, and so on, add a virtual member. - Move the code from the default implementation of the 'virtual interfaces' to the new virtual members.

- Delete the dependency fields and remove the corresponding arguments from the constructor.

- Clean up orphaned interfaces and implementations.

Example: Gang of Four maze Builder as an abstract class #

As an example, consider the original Gang of Four example of the Builder pattern. The example in the book is based on an abstract class called MazeBuilder. Translated to C#, it looks like this:

public abstract class MazeBuilder { public virtual void BuildMaze() { } public virtual void BuildRoom(int room) { } public virtual void BuildDoor(int roomFrom, int roomTo) { } public abstract Maze GetMaze(); }

In the book, all four methods are virtual, because:

"They're not declared pure virtual to let derived classes override only those methods in which they're interested."When it comes to the

GetMaze method, this means that the method in the book returns a null reference by default. Since this seems like poor API design, and also because the example becomes more illustrative if the class has both abstract and virtual members, I changed it to be abstract (i.e. pure virtual).

In general, there are various other issues with this design, the most glaring of which is the implied sequence coupling between members: you're expected to call BuildMaze before any of the other methods. A better design would be to remove that explicit step entirely, or else turn it into a factory that you have to call in order to be able to call the other methods. That's not the topic of the present article, so I'll leave the API like this.

The book also shows a simple usage example of the abstract MazeBuilder class:

public class MazeGame { public Maze CreateMaze(MazeBuilder builder) { builder.BuildMaze(); builder.BuildRoom(1); builder.BuildRoom(2); builder.BuildDoor(1, 2); return builder.GetMaze(); } }

You use it with e.g. a StandardMazeBuilder like this:

var game = new MazeGame(); var builder = new StandardMazeBuilder(); var maze = game.CreateMaze(builder);

You could also, again following the book's example as closely as possible, use it with a CountingMazeBuilder, like this:

var game = new MazeGame(); var builder = new CountingMazeBuilder(); game.CreateMaze(builder); var msg = $"The maze has {builder.RoomCount} rooms and {builder.DoorCount} doors.";

This would produce "The maze has 2 rooms and 1 doors.".

Both StandardMazeBuilder and CountingMazeBuilder are concrete classes that derive from the abstract MazeBuilder class.

Maze Builder refactored to interfaces #

If you follow the refactoring outline in this article, you can refactor the above MazeBuilder class to a set of interfaces. The first should be an interface extracted from all the pure virtual members of the class. In this example, there's only one such member, so the interface becomes this:

public interface IMazeBuilder { Maze GetMaze(); }

The three virtual members each get their own interface, so that you can pick and choose which of them you want to override, and which of them you prefer to keep with their default implementation (which, in this particular case, is to do nothing).

The first one was difficult to name:

public interface IMazeInitializer { void BuildMaze(); }

An interface with a single method called BuildMaze would naturally have a name like IMazeBuilder, but unfortunately, I just used that name for the previous interface. The reason I named the above interface IMazeBuilder is because this is an interface extracted from the MazeBuilder abstract class, and I consider the pure virtual API to be the core API of the abstraction, so I think it makes most sense to keep the name for that interface. Thus, I had to come up with a smelly name like IMazeInitializer.

Fortunately, the two remaining interfaces are a little better:

public interface IRoomBuilder { void BuildRoom(int room); } public interface IDoorBuilder { void BuildDoor(int roomFrom, int roomTo); }

The three virtual members all had default implementations, so you need to keep those around. You can do that by moving the methods' code to a new class that implements the new interfaces:

public class DefaultMazeBuilder : IMazeInitializer, IRoomBuilder, IDoorBuilder

In this example, there's no reason to show the implementation of the class, because, as you may recall, all three methods are no-ops.

Instead of inheriting from MazeBuilder, implementers now implement the appropriate interfaces:

public class StandardMazeBuilder : IMazeBuilder, IMazeInitializer, IRoomBuilder, IDoorBuilder

This version of StandardMazeBuilder implements all four interfaces, since, before, it overrode all four methods. CountingMazeBuilder, on the other hand, never overrode BuildMaze, so it doesn't have to implement IMazeInitializer:

public class CountingMazeBuilder : IRoomBuilder, IDoorBuilder, IMazeBuilder

All of these changes leaves the original MazeBuilder class defined like this:

public class MazeBuilder : IMazeBuilder, IMazeInitializer, IRoomBuilder, IDoorBuilder { private readonly IMazeBuilder mazeBuilder; private readonly IMazeInitializer mazeInitializer; private readonly IRoomBuilder roomBuilder; private readonly IDoorBuilder doorBuilder; public MazeBuilder( IMazeBuilder mazeBuilder, IMazeInitializer mazeInitializer, IRoomBuilder roomBuilder, IDoorBuilder doorBuilder) { this.mazeBuilder = mazeBuilder; this.mazeInitializer = mazeInitializer; this.roomBuilder = roomBuilder; this.doorBuilder = doorBuilder; } public void BuildMaze() { this.mazeInitializer.BuildMaze(); } public void BuildRoom(int room) { this.roomBuilder.BuildRoom(room); } public void BuildDoor(int roomFrom, int roomTo) { this.doorBuilder.BuildDoor(roomFrom, roomTo); } public Maze GetMaze() { return this.mazeBuilder.GetMaze(); } }

At this point, you may decide to keep the old MazeBuilder class around, because you may have other code that relies on it. Notice, however, that it's now a concrete class that has dependencies injected into it via its constructor. All four members only delegate to the relevant dependencies in order to do actual work.

MazeGame looks like before, but calling CreateMaze looks more complicated:

var game = new MazeGame(); var builder = new StandardMazeBuilder(); var maze = game.CreateMaze(new MazeBuilder(builder, builder, builder, builder));

Notice that while you're passing four dependencies to the MazeBuilder constructor, you can reuse the same StandardMazeBuilder object for all four roles.

If you want to count the rooms and doors, however, CountingMazeBuilder doesn't implement IMazeInitializer, so for that role, you'll need to use the default implementation:

var game = new MazeGame(); var builder = new CountingMazeBuilder(); game.CreateMaze(new MazeBuilder(builder, new DefaultMazeBuilder(), builder, builder)); var msg = $"The maze has {builder.RoomCount} rooms and {builder.DoorCount} doors.";

If, at this point, you're beginning to wonder what value MazeBuilder adds, then I think that's a legitimate concern. What often happens, then, is that you simply remove that extra layer.

Mazes without MazeBuilder #

When you delete the MazeBuilder class, you'll have to adjust MazeGame accordingly:

public class MazeGame { public Maze CreateMaze( IMazeInitializer initializer, IRoomBuilder roomBuilder, IDoorBuilder doorBuilder, IMazeBuilder mazeBuilder) { initializer.BuildMaze(); roomBuilder.BuildRoom(1); roomBuilder.BuildRoom(2); doorBuilder.BuildDoor(1, 2); return mazeBuilder.GetMaze(); } }

The CreateMaze method now simply takes the four interfaces on which it relies as individual arguments. This simplifies the client code as well:

var game = new MazeGame(); var builder = new StandardMazeBuilder(); var maze = game.CreateMaze(builder, builder, builder, builder);

You can still reuse a single StandardMazeBuilder in all roles, but again, if you only want to count the rooms and doors, you'll have to rely on DefaultMazeBuilder for the behaviour that CountingMazeBuilder doesn't define:

var game = new MazeGame(); var builder = new CountingMazeBuilder(); game.CreateMaze(new DefaultMazeBuilder(), builder, builder, builder); var msg = $"The maze has {builder.RoomCount} rooms and {builder.DoorCount} doors.";

The order in which dependencies are passed to CreateMaze is different than the order they were passed to the now-deleted MazeBuilder constructor, so you'll have to pass a new DefaultMazeBuilder() as the first argument in order to fill the role of IMazeInitializer. Another way to address this issue is to supply various overloads of the CreateMaze method that uses DefaultMazeBuilder for the behaviour that you don't want to override.

Summary #

Many of the original design patterns in Design Patterns are described with examples in C++, and many of these examples use abstract classes as the programming interfaces that the Gang of Four really had in mind when they wrote that we should be programming to interfaces instead of implementations.

The most important result of this article is that you can reinterpret the original design patterns with C# or Java interfaces and Dependency Injection, instead of using abstract classes. I've done this in C# for more than ten years, and in my experience, you never need abstract classes in a greenfield code base. There's always an equivalent representation that involves composition of interfaces.

Object isomorphisms

An object is equivalent to a product of functions. Alternative ways to look at objects.

This article is part of a series of articles about software design isomorphisms. So far, you've seen how to represent a single method or function in many different ways, but we haven't looked much at objects (in the object-oriented interpretation of the word).

While this article starts by outlining the abstract concepts involved, an example is included towards the end.

Objects as data with behaviour #

I often use the phrase that objects are data with behaviour. (I'm sure I didn't come up with this myself, but the source of the phrase escapes me.) In languages like C# and Java, objects are described by classes, and these often contain class fields. These fields constitute an instance's data, whereas its methods implement its behaviour.

A class can contain an arbitrary number of fields, just like a method can take an arbitrary number of arguments. As demonstrated by the argument list isomorphisms, you can also represent an arbitrary number of arguments as a Parameter Object. The same argument can be applied to class fields. Instead of n fields, you can add a single 'data class' that holds all of these fields. In F# and Haskell these are called records. You could also dissolve such a record to individual fields. That would be the inverse refactoring, so these representations are isomorphic.

In other words, a class looks like this:

public class Class1 { public Data1 Data { get; set; } public Out1 Op1(In1 arg) { // Do stuff with this, Data, and arg; return an Out1 value. } public Out2 Op2(In2 arg) { // Do stuff with this, Data, and arg; return an Out1 value. } public Out3 Op3(In3 arg) { // Do stuff with this, Data, and arg; return an Out1 value. } // More members... }

Instead of an arbitrary number of fields, I've used the above isomorphism to represent data in a single Data property (Java developers: a C# property is a class field with public getter and setter methods).

In this code example, I've deliberately kept the naming abstract. The purpose of this article series is to look at the shape of code, instead of what it does, or why. From argument list isomorphisms we know that we can represent any method as taking a single input value, and returning a single output value. The remaining work to be done in this article is to figure out what to do when there's more than a single method.

Module #

From function isomorphisms we know that static methods are isomorphic to instance methods, as long as you include the original object as an extra argument. In this case, all data in Class1 is contained in a single (mutable) Data1 record, so we can eliminate Class1 from the argument list in favour of Data1:

public static class Class1 { public static Out1 Op1(Data1 data, In1 arg) { // Do stuff with data and arg; return an Out1 value. } public static Out2 Op2(Data1 data, In2 arg) { // Do stuff with data and arg; return an Out1 value. } public static Out3 Op3(Data1 data, In3 arg) { // Do stuff with data and arg; return an Out1 value. } // More members... }

Notice that Class1 is now a static class. This simply means that it has no instance members, and if you try to add one, the C# compiler will complain.

This is, in essence, a module. In F#, for example, a module is a static class that contains a collection of values and functions.

Closures as behaviour with data #

As data with behaviour, objects are often passed around as input to methods. It's a convenient way to pass both data and associated behaviour (perhaps even with polymorphic dispatch) as a single thing. You'd be forgiven if you've looked at the above module-style refactoring and found it lacking in that regard.

Nevertheless, function isomorphisms already demonstrated that you can solve this problem with closures. Imagine that you want to package all the static methods of Class1 with a particular Data1 value, and pass that 'package' as a single argument to another method. You can do that by closing over the value:

var data = new Data1 { /* initialize members here */ }; Func<In1, Out1> op1 = arg => Class1.Op1(data, arg); Func<In2, Out2> op2 = arg => Class1.Op2(data, arg); Func<In3, Out3> op3 = arg => Class1.Op3(data, arg); // More closures...

First, you create a Data1 value, and initialise it with your desired values. You then create op1, op2, and so on. These are functions that close over data; A.K.A. closures. Notice that they all close over the same variable. Also keep in mind here that I'm in no way pretending that data is immutable. That's not a requirement.

Now you have n closures that all close over the same data. All you need to do is to package them into a single 'object':

var objEq = Tuple.Create(op1, op2, op3 /* more closures... */);

Once again, tuples are workhorses of software design isomorphisms. objEq is an 'object equivalent' consisting of closures; it's behaviour with data. You can now pass objEq as an argument to another method, if that's what you need to do.

Isomorphism #

One common variation that I sometimes see is that instead of a tuple of functions, you can create a record of functions. This enables you to give each function a statically enforced name. In the theory of algebraic data types, tuples and records are both product types, so when looking at the shape of code, these are closely related. Records also enable you to preserve the name of each method, so that this mapping from object to record of functions becomes lossless.

The inverse mapping also exists. If you have a record of functions, you can refactor it to a class. You use the name of each record element as a method name, and the arguments and return types to further flesh out the methods.

Example: simplified Turtle #

As an example, consider this (over-)simplified Turtle class:

public class Turtle { public double X { get; private set; } public double Y { get; private set; } public double AngleInDegrees { get; private set; } public Turtle() { } public Turtle(double x, double y, double angleInDegrees) { this.X = x; this.Y = y; this.AngleInDegrees = angleInDegrees; } public void Turn(double angleInDegrees) { this.AngleInDegrees = (this.AngleInDegrees + angleInDegrees) % 360; } public void Move(double distance) { // Convert degrees to radians with 180.0 degrees = 1 pi radian var angleInRadians = this.AngleInDegrees * (Math.PI / 180); this.X = this.X + (distance * Math.Cos(angleInRadians)); this.Y = this.Y + (distance * Math.Sin(angleInRadians)); } }

In order to keep the example simple, the only operations offered by the Turtle class is Turn and Move. With this simplified API, you can create a turtle object and interact with it:

var turtle = new Turtle(); turtle.Move(2); turtle.Turn(90); turtle.Move(1);

This sequence of operations will leave turtle as position (2, 1) and an angle of 90°.

Instead of modelling a turtle as an object, you can instead model it as a data structure and a set of (impure) functions:

public class TurtleData { private double x; private double y; private double angleInDegrees; public TurtleData() { } public TurtleData(double x, double y, double angleInDegrees) { this.x = x; this.y = y; this.angleInDegrees = angleInDegrees; } public static void Turn(TurtleData data, double angleInDegrees) { data.angleInDegrees = (data.angleInDegrees + angleInDegrees) % 360; } public static void Move(TurtleData data, double distance) { // Convert degrees to radians with 180.0 degrees = 1 pi radian var angleInRadians = data.angleInDegrees * (Math.PI / 180); data.x = data.x + (distance * Math.Cos(angleInRadians)); data.y = data.y + (distance * Math.Sin(angleInRadians)); } public static double GetX(TurtleData data) { return data.x; } public static double GetY(TurtleData data) { return data.y; } public static double GetAngleInDegrees(TurtleData data) { return data.angleInDegrees; } }

Notice that all five static methods take a TurtleData value as their first argument, just as the above abstract description suggests. The implementations are almost identical; you simply replace this with data. If you're a C# developer, you may be wondering about the accessor functions GetX, GetY, and GetAngleInDegrees. These are, however, the static equivalents to the Turtle class X, Y, and AngleInDegrees properties. Keep in mind that in C#, a property is nothing but syntactic sugar over one (or two) IL methods (e.g. get_X()).

You can now create a pentuple (a five-tuple) of closures over those five static methods and a single TurtleData object. While you can always do that from scratch, it's illuminating to transform a Turtle into such a tuple, thereby illustrating how that morphism looks:

public Tuple<Action<double>, Action<double>, Func<double>, Func<double>, Func<double>> ToTuple() { var data = new TurtleData(this.X, this.Y, this.AngleInDegrees); Action<double> turn = angle => TurtleData.Turn(data, angle); Action<double> move = distance => TurtleData.Move(data, distance); Func<double> getX = () => TurtleData.GetX(data); Func<double> getY = () => TurtleData.GetY(data); Func<double> getAngle = () => TurtleData.GetAngleInDegrees(data); return Tuple.Create(turn, move, getX, getY, getAngle); }

This ToTuple method is an instance method on Turtle (I just held it back from the above code listing, in order to list it here instead). It creates a new TurtleData object from its current state, and proceeds to close over it five times - each time delegating the closure implementation to the corresponding static method. Finally, it creates a pentuple of those five closures.

You can interact with the pentuple just like it was an object:

var turtle = new Turtle().ToTuple(); turtle.Item2(2); turtle.Item1(90); turtle.Item2(1);

The syntax is essentially the same as before, but clearly, this isn't as readable. You have to remember that Item2 contains the move closure, Item1 the turn closure, and so on. Still, since they are all delegates, you can call them as though they are methods.

I'm not trying to convince you that this sort of design is better, or even equivalent, in terms of readability. Clearly, it isn't - at least in C#. The point is, however, that from a perspective of structure, these two models are equivalent. Everything you can do with an object, you can also do with a tuple of closures.

So far, you've seen that you can translate a Turtle into a tuple of closures, but in order to be an isomorphism, the reverse translation should also be possible.

One way to translate from TurtleData to Turtle is with this static method (i.e. function):

public static Turtle ToTurtle(TurtleData data) { return new Turtle(data.x, data.y, data.angleInDegrees); }

Another option for making the pentuple of closures look like an object is to extract an interface from the original Turtle class:

public interface ITurtle { void Turn(double angleInDegrees); void Move(double distance); double X { get; } double Y { get; } double AngleInDegrees { get; } }

Not only can you let Turtle implement this interface (public class Turtle : ITurtle), but you can also define an Adapter:

public class TupleTurtle : ITurtle { private readonly Tuple<Action<double>, Action<double>, Func<double>, Func<double>, Func<double>> imp; public TupleTurtle( Tuple<Action<double>, Action<double>, Func<double>, Func<double>, Func<double>> imp) { this.imp = imp; } public void Turn(double angleInDegrees) { this.imp.Item1(angleInDegrees); } public void Move(double distance) { this.imp.Item2(distance); } public double X { get { return this.imp.Item3(); } } public double Y { get { return this.imp.Item4(); } } public double AngleInDegrees { get { return this.imp.Item5(); } } }

This class simply delegates all its behaviour to the implementing pentuple. It can be used like this with no loss of readability:

var turtle = new TupleTurtle(TurtleData.CreateDefault()); turtle.Move(2); turtle.Turn(90); turtle.Move(1);

This example utilises this creation function:

public static Tuple<Action<double>, Action<double>, Func<double>, Func<double>, Func<double>> CreateDefault() { var data = new TurtleData(); Action<double> turn = angle => TurtleData.Turn(data, angle); Action<double> move = distance => TurtleData.Move(data, distance); Func<double> getX = () => TurtleData.GetX(data); Func<double> getY = () => TurtleData.GetY(data); Func<double> getAngle = () => TurtleData.GetAngleInDegrees(data); return Tuple.Create(turn, move, getX, getY, getAngle); }

This function is almost identical to the above ToTuple method, and those two could easily be refactored to a single method.

This example demonstrates how an object can also be viewed as a tuple of closures, and that translations exist both ways between those two views.

Conclusion #

To be clear, I'm not trying to convince you that it'd be great if you wrote all of your C# or Java using tuples of closures; it most likely wouldn't be. The point is that a class is isomorphic to a tuple of functions.

From category theory, and particular its application to Haskell, we know quite a bit about the properties of certain functions. Once we start to look at objects as tuples of functions, we may be able to say something about the properties of objects, because category theory also has something to say about the properties of tuples (for example that a tuple of monoids is itself a monoid).

Next: Abstract class isomorphism.

Uncurry isomorphisms

Curried functions are isomorphic to tupled functions.

This article is part of a series of articles about software design isomorphisms. Nota bene: it's not about Curry–Howard isomorphism. In order to prevent too much confusion, I chose the title Uncurry isomorphism over Curry isomorphism.

The Haskell base library includes two functions called curry and uncurry, and for anyone aware of them, it should be no surprise that they are each others' inverses. This is another important software design isomorphism, because in the previous article, you saw that all methods can be represented in tupled form. The current isomorphism then extends that result because tupled and curried forms are isomorphic.

An F# introduction to curry and uncurry #

While Haskell programmers are likely to be familiar with curry and uncurry, developers more familiar with other languages may not know them well. In this section follows an introduction in F#. Haskellers can skip it if they like.

In F#, you often have to interoperate with code written in C#, and as the previous article explained, all such methods look to F# like functions taking a single tuple as input. Sometimes, however, you'd wish they were curried.

This little function can help with that:

// ('a * 'b -> 'c) -> 'a -> 'b -> 'c let curry f x y = f (x, y)

You'll probably have to look at it for a while, and perhaps play with it, before it clicks, but it does this: it takes a function (f) that takes a tuple ('a * 'b) as input, and returns a new function that does the same, but instead takes the arguments in curried form: 'a -> 'b -> 'c.

It can be useful in interoperability scenarios. Imagine, as a toy example, that you have to list the powers of two from 0 to 10. You can use Math.Pow, but since it was designed with C# in mind, its argument is a single tuple. curry to the rescue:

> List.map (curry Math.Pow 2.) [0.0..10.0];; val it : float list = [1.0; 2.0; 4.0; 8.0; 16.0; 32.0; 64.0; 128.0; 256.0; 512.0; 1024.0]

While Math.Pow has the type float * float -> float, curry Math.Pow turns it into a function with the type float -> float -> float. Since that function is curried, it can be partially applied with the value 2., which returns a function of the type float -> float. That's a function you can use with List.map.

You'd hardly be surprised that you can also uncurry a function:

// ('a -> 'b -> 'c) -> 'a * 'b -> 'c let uncurry f (x, y) = f x y

This function takes a curried function f, and returns a new function that does the same, but instead takes a tuple as input.

Pair isomorphism #

Haskell comes with curry and uncurry as part of its standard library. It hardly comes as a surprise that they form an isomorphism. You can demonstrate this with some QuickCheck properties.

If you have a curried function, you should be able to first uncurry it, then curry that function, and that function should be the same as the original function. In order to demonstrate that, I chose the (<>) operator from Data.Semigroup. Recall that Haskell operators are curried functions. This property function demonstrates the round-trip property of uncurry and curry:

semigroup2RoundTrips :: (Semigroup a, Eq a) => a -> a -> Bool semigroup2RoundTrips x y = x <> y == curry (uncurry (<>)) x y

This property states that the result of combining two semigroup values is the same as first uncurrying (<>), and then 'recurry' it. It passes for various Semigroup instances:

testProperty "All round-trips" (semigroup2RoundTrips :: All -> All -> Bool), testProperty "Any round-trips" (semigroup2RoundTrips :: Any -> Any -> Bool), testProperty "First round-trips" (semigroup2RoundTrips :: First Int -> First Int -> Bool), testProperty "Last round-trips" (semigroup2RoundTrips :: Last Int -> Last Int -> Bool), testProperty "Sum round-trips" (semigroup2RoundTrips :: Sum Int -> Sum Int -> Bool), testProperty "Product round-trips" (semigroup2RoundTrips :: Product Int -> Product Int -> Bool)

It's not a formal proof that all of these properties pass, but it does demonstrate the isomorphic nature of these two functions. In order to be truly isomorphic, however, you must also be able to start with a tupled function. In order to have a similar tupled function, I defined this:

t2sg :: Semigroup a => (a, a) -> a t2sg (x, y) = x <> y

The t2 in the name stands for tuple-2, and sg means semigroup. It really only exposes (<>) in tupled form. With it, though, you can write another property that demonstrates that the mapping starting with a tupled form is also an isomorphism:

pairedRoundTrips :: (Semigroup a, Eq a) => a -> a -> Bool pairedRoundTrips x y = t2sg (x, y) == uncurry (curry t2sg) (x, y)

You can create properties for the same instances of Semigroup as the above list for semigroup2RoundTrips, and they all pass as well.

Triplet isomorphism #

curry and uncurry only works for pairs (two-tuples) and functions that take exactly two curried arguments. What if you have a function that takes three curried arguments, or a function that takes a triplet (three-tuple) as an argument?

First of all, while they aren't built-in, you can easily define corresponding mappings for those as well:

curry3 :: ((a, b, c) -> d) -> a -> b -> c -> d curry3 f x y z = f (x, y, z) uncurry3 :: (a -> b -> c -> d) -> (a, b, c) -> d uncurry3 f (x, y, z) = f x y z

These form an isomorphism as well.

More generally, though, you can represent a triplet (a, b, c) as a nested pair: (a, (b, c)). These two representations are also isomorphic, as is (a, b, c, d) with (a, (b, (c, d))). In other words, you can represent any n-tuple as a nested pair, and you already know that a function taking a pair as input is isomorphic to a curried function.

Summary #

From abstract algebra, and particularly its application to a language like Haskell, we have mathematical abstractions over computation - semigroups, for example! In Haskell, these abstractions are often represented in curried form. If we wish to learn about such abstractions, and see if we can use them in object-oriented programming as well, we need to translate the curried representations into something more closely related to object-oriented programming, such as C# or Java.

The present article describes how functions in curried form are equivalent to functions that take a single tuple as argument, and in a previous article, you saw how such functions are isomorphic to C# or Java methods. These equivalences provide a bridge that enables us to take what we've learned about abstract algebra and category theory, and bring them to object-oriented programming.

Next: Object isomorphisms.

Argument list isomorphisms

There are many ways to represent an argument list. An overview for object-oriented programmers.

This article is part of a series of articles about software design isomorphisms.

Most programming languages enable you to pass arguments to operations. In C# and Java, you declare methods with a list of arguments:

public Foo Bar(Baz baz, Qux qux)

Here, baz and qux are arguments to the Bar method. Together, the arguments for a method is called an argument list. To be clear, this isn't universally adopted terminology, but is what I'll be using in this article. Sometimes, people (including me) say parameter instead of argument, and I'm not aware of any formal specification to differentiate the two.

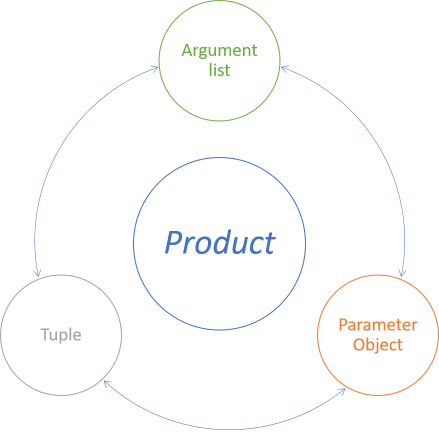

While you can pass arguments as a flat list, you can also model them as parameter objects or tuples. These representations are equivalent, because lossless translations between them exist. We say that they are isomorphic.

Isomorphisms #

In theory, you can declare a method that takes thousands of arguments. In practice, you should constrain your design to as few arguments as possible. As Refactoring demonstrates, one way to do that is to Introduce Parameter Object. That, already, teaches us that there's a mapping from a flat argument list to a Parameter Object. Is there an inverse mapping? Do other representations exist?

There's at least three alternative representations of a group of arguments:

- Argument list

- Parameter Object

- Tuple

Argument list/Parameter Object isomorphism #

Perhaps the best-known mapping from an argument list is the Introduce Parameter Object refactoring described in Refactoring.

Since the refactoring is described in detail in the book, I don't want to repeat it all here, but in short, assume that you have a method like this:

public Bar Baz(Qux qux, Corge corge)

In this case, the method only has two arguments, so the refactoring may not be necessary, but that's not the point. The point is that it's possible to refactor the code to this:

public Bar Baz(BazParameter arg)

where BazParameter looks like this:

public class BazParameter { public Qux Qux { get; set; } public Corge Corge { get; set; } }

In Refactoring, the recipe states that you should make the class immutable, and while that's a good idea (I recommend it!), it's technically not necessary in order to perform the translation, so I omitted it here in order to make the code simpler.

You're probably able to figure out how to translate back again. We could call this refactoring Dissolve Parameter Object:

- For each field or property in the Parameter Object, add a new method argument to the target method.

- At all call sites, pass the Parameter Object's field or property value as each of those new arguments.

- Change the method body so that it uses each new argument, instead of the Parameter Object.

- Remove the Parameter Object argument, and update call sites accordingly.

As an example, consider the Roster example from a previous article. The Combine method on the Roster class is implemented like this:

public Roster Combine(Roster other) { return new Roster( this.Girls + other.Girls, this.Boys + other.Boys, this.Exemptions.Concat(other.Exemptions).ToArray()); }

This method takes an object as a single argument. You can think of this Roster object as a Parameter Object.

If you like, you can add a method overload that dissolves the Roster object to its constituent values:

public Roster Combine( int otherGirls, int otherBoys, params string[] otherExemptions) { return this.Combine( new Roster(otherGirls, otherBoys, otherExemptions)); }

In this incarnation, the dissolved method overload creates a new Roster from its argument list and delegates to the other overload. This is, however, an arbitrary implementation detail. You could just as well implement the two methods the other way around:

public Roster Combine(Roster other) { return this.Combine( other.Girls, other.Boys, other.Exemptions.ToArray()); } public Roster Combine( int otherGirls, int otherBoys, params string[] otherExemptions) { return new Roster( this.Girls + otherGirls, this.Boys + otherBoys, this.Exemptions.Concat(otherExemptions).ToArray()); }

In this variation, the overload that takes three arguments contains the implementation, whereas the Combine(Roster) overload simply delegates to the Combine(int, int, string[]) overload.

In order to illustrate the idea that both APIs are equivalent, in this example I show two method overloads side by side. The overall point, however, is that you can translate between such two representations without changing the behaviour of the system. You don't have to keep both method overloads in place together.

Argument list/tuple isomorphism #

In relationship to statically typed functional programming, the term argument list is confounding. In the functional programming languages I've so far dabbled with (F#, Haskell, PureScript, Clojure, Erlang), the word list is used synonymously with linked list.

As a data type, a linked list can hold an arbitrary number of elements. (In Haskell, it can even be infinite, because Haskell is lazily evaluated.) Statically typed languages like F# and Haskell add the constraint that all elements must have the same type.

An argument list like (Qux qux, Corge corge) isn't at all a statically typed linked list. Neither does it have an arbitrary size nor does it contain elements of the same type. On the contrary, it has a fixed length (two), and elements of different types. The first element must be a Qux value, and the second element must be a Corge value.

That's not a list; that's a tuple.

Surprisingly, Haskell may provide the most digestible illustration of that, even if you don't know how to read Haskell syntax. Suppose you have the values qux and corge, of similarly named types. Consider a C# method call Baz(qux, corge). What's the type of the 'argument list'?

λ> :type (qux, corge) (qux, corge) :: (Qux, Corge)

:type is a GHCi command that displays the type of an expression. By coincidence (or is it?), the C# argument list (qux, corge) is also valid Haskell syntax, but it is syntax for a tuple. In this example, the tuple is a pair where the first element has the type Qux, and the second element has the type Corge, but (foo, qux, corge) would be a triple, (foo, qux, corge, grault) would be a quadruple, and so on.

We know that the argument list/tuple isomorphism exists, because that's how the F# compiler works. F# is a multi-paradigmatic language, and it can interact with C# code. It does that by treating all C# argument lists as tuples. Consider this example of calling Math.Pow:

let i = Math.Pow(2., 4.)

Programmers who still write more C# than F# often write it like that, because it looks like a method call, but I prefer to insert a space between the method and the arguments:

let i = Math.Pow (2., 4.)

The reason is that in F#, function calls are delimited with space. The brackets are there in order to override the normal operator precedence, just like you'd write (1 + 2) * 3 in order to get 9 instead of 7. This is better illustrated by introducing an intermediate value:

let t = (2., 4.) let i = Math.Pow t

or even

let t = 2., 4. let i = Math.Pow t

because the brackets are now redundant. In the last two examples, t is a tuple of two floating-point numbers. All four code examples are equivalent and compile, thereby demonstrating that a translation exist from F# tuples to C# argument lists.

The inverse translation exists as well. You can see a demonstration of this in the (dormant) Numsense code base, which includes an object-oriented Façade, which defines (among other things) an interface where the TryParse method takes a tuple argument. Here's the declaration of that method:

abstract TryParse : s : string * [<Out>]result : int byref -> bool

That looks cryptic, but if you remove the [<Out>] annotation and the argument names, the method is declared as taking single input value of the type string * int byref. It's a single value, but it's a tuple (a pair).

Perhaps it's easier to understand if you see an implementation of this interface method, so here's the English implementation:

member this.TryParse (s, result) = Helper.tryParse Numeral.tryParseEnglish (s, &result)

You can see that, as I've described above, I've inserted a space between this.TryParse and (s, result), in order to highlight that this is an F# function that takes a single tuple as input.

In C#, however, you can use the method as though it had a standard C# argument list:

int i; var success = Numeral.English.TryParse( "one-thousand-three-hundred-thirty-seven", out i);

You'll note that this is an advanced example that involves an out parameter, but even in this edge case, the translation is possible.

C# argument lists and F# tuples are isomorphic. I'd be surprised if this result doesn't extend to other languages.

Parameter Object/tuple isomorphism #

The third isomorphism that I claim exists is the one between Parameter Objects and tuples. If, however, we assume that the two above isomorphisms hold, then this third isomorphism exists as well. I know from my copy of Conceptual Mathematics that isomorphisms are transitive. If you can translate from Parameter Object to argument list, and from argument list to tuple, then you can translate from Parameter Object to tuple; and vice versa.

Thus, I'm not going to use more words on this isomorphism.

Summary #

Argument lists, Parameter Objects, and tuples are isomorphic. This has a few interesting implications, first of which is that because all these refactorings exist, you can employ them. If a method's argument list is inconvenient, consider introducing a Parameter Object. If your Parameter Object starts to look so generic that you have a hard time coming up with good names for its elements, perhaps a tuple is more appropriate. On the other hand, if you have a tuple, but it's unclear what role each unnamed element plays, consider refactoring to an argument list or Parameter Object.

Another important result is that since these three ways to model arguments are isomorphic, we can treat them as interchangeable in analysis. For instance, from category theory we can learn about the properties of tuples. These properties, then, also apply to C# and Java argument lists.

Next: Uncurry isomorphisms.

Function isomorphisms

Instance methods are isomorphic to functions.

This article is part of a series of articles about software design isomorphisms.

While I have already, in an earlier article, quoted the following parable about Anton, Qc Na, objects, and closures, it's too good a fit to the current topic to pass up, so please pardon the duplication.

The venerable master Qc Na was walking with his student, Anton. Hoping to prompt the master into a discussion, Anton said "Master, I have heard that objects are a very good thing - is this true?" Qc Na looked pityingly at his student and replied, "Foolish pupil - objects are merely a poor man's closures."

Chastised, Anton took his leave from his master and returned to his cell, intent on studying closures. He carefully read the entire "Lambda: The Ultimate..." series of papers and its cousins, and implemented a small Scheme interpreter with a closure-based object system. He learned much, and looked forward to informing his master of his progress.

On his next walk with Qc Na, Anton attempted to impress his master by saying "Master, I have diligently studied the matter, and now understand that objects are truly a poor man's closures." Qc Na responded by hitting Anton with his stick, saying "When will you learn? Closures are a poor man's object." At that moment, Anton became enlightened.

The point is that objects and closures are two ways of looking at a thing. In a nutshell, objects are data with behaviour, whereas closures are behaviour with data. I've already shown an elaborate C# example of this, so in this article, you'll get a slightly more formal treatment of the subject.

Isomorphism #

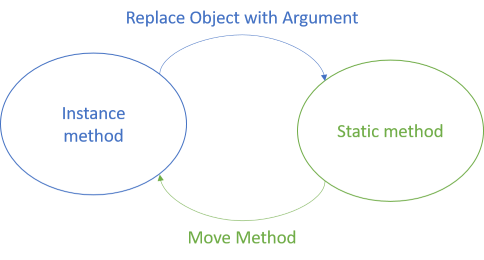

In object-oriented design, you often bundle operations as methods that belong to objects. These are isomorphic to static methods, because a lossless translation exists. We can call such static methods functions, although they aren't guaranteed to be pure.

In the spirit of Refactoring, we can describe each translation as a refactoring, because that's what it is. I don't think the book contains a specific refactoring that describes how to translate from an instance method to a static method, but we could call it Replace Object with Argument.

Going the other way is, on the other hand, already described, so we can use Refactoring's Move Method.

Replace Object with Argument #

While the concept of refactoring ought to be neutral across paradigms, the original book is about object-oriented programming. In object-oriented programming, objects are the design ideal, so it didn't make much sense to include, in the book, a refactoring that turns an instance method into a static method.

Nevertheless, it's straightforward:

- Add an argument to the instance method. Declare the argument as the type of the hosting class.

- In the method body, change all calls to

thisandbaseto the new argument. - Make the method static.

Baz method:

public class Foo { public Bar Baz(Qux qux, Corge corge) { // Do stuff, return bar } // Other members... }

You'll first introduce a new Foo foo argument to Baz, change the method body to use foo instead of this, and then make the method static. The result is this:

public class Foo { public static Bar Baz(Foo foo, Qux qux, Corge corge) { // Do stuff, return bar } // Other members... }

Once you have a static method, you can always move it to another class, if you'd like. This can, however, cause some problems with accessibility. In C#, for example, you'd no longer be able to access private or protected members from a method outside the class. You can choose to leave the static method reside on the original class, or you can make the member in question available to more clients (make it internal or public).

Move Method #

The book Refactoring doesn't contain a recipe like the above, because the goal of that book is better object-oriented design. It would consider a static method, like the second variation of Baz above, a code smell named Feature Envy. You have this code smell when it looks as if a method is more interested in one of its arguments than in its host object. In that case, the book suggests using the Move Method refactoring.

The book already describes this refactoring, so I'm not going to repeat it here. Also, there's no sense in showing you the code example, because it's literally the same two code examples as above, only in the opposite order. You start with the static method and end with the instance method.

C# developers are most likely already aware of this relationship between static methods and objects, because you can use the this keyword in a static method to make it look like an instance method:

public static Bar Baz(this Foo foo, Qux qux, Corge corge)

The addition of this in front of the Foo foo argument enables the C# compiler to treat the Baz method as though it's an instance method on a Fooobject:

var bar = foo.Baz(qux, corge);

This is only syntactic sugar. The method is still compiled as a static method, and if you, as a client developer, wish to use it as a static method, that's still possible.

Functions #

A static method like public static Bar Baz(Foo foo, Qux qux, Corge corge) looks a lot like a function. If refactored from object-oriented design, that function is likely to be impure, but its shape is function-like.

In C#, for example, you could model it as a variable of a delegate type:

Func<Foo, Qux, Corge, Bar> baz = (foo, qux, corge) => { // Do stuff, return bar };

Here, baz is a function with the same signature as the above static Baz method.

Have you ever noticed something odd about the various Func delegates in C#?

They take the return type as the last type argument, which is contrary to C# syntax, where you have to declare the return type before the method name and argument list. Since C# is the dominant .NET language, that's surprising, and even counter-intuitive.

It does, however, nicely align with an ML language like F#. As we'll see in a future article, the above baz function translates to an F# function with the type Foo * Qux * Corge -> Bar, and to Haskell as a function with the type (Foo, Qux, Corge) -> Bar. Notice that the return type comes last, just like in the C# Func.

Closures #

...but, you may say, what about data with behaviour? One of the advantages, after all, of objects is that you can associate a particular collection of data with some behaviour. The above Foo class could have data members, and you may sometimes have a need for passing both data and behaviour around as a single... well... object.

That seems to be much harder with a static Baz method.

Don't worry, write a closure:

var foo = new Foo { /* initialize members here */ }; Func<Qux, Corge, Bar> baz = (qux, corge) => { // Do stuff with foo, qux, and corge; return bar };

In this variation, baz closes over foo. Inside the function body, you can use foo like you can use qux and corge. As I've already covered in an earlier article, the C# compiler compiles this to an IL class, making it even more obvious that objects and closures are two sides of the same coin.

Summary #

Object-oriented instance methods are isomorphic to both static methods and function values. The translations that transforms your code from one to the other are refactorings. Since you can move in both directions without loss of information, these refactorings constitute an isomorphism.

This is another important result about the relationship between object-oriented design and functional programming, because this enables us to reduce any method to a canonical form, in the shape of a function. From a language like Haskell, we know a lot about the relationship between category theory and functional programming. With isomorphisms like the present, we can begin to extend that knowledge to object-oriented design.

Next: Argument list isomorphisms.

Comments

This Isomorphism applies to non-polymorphic Methods. Polymorphic Functions need to be mapped to a Set is static Methods with the same Signature. Is there a functional Construct for this?

Matt, thank you for writing. What makes you write that this isomorphism applies (only, I take it) to non-polymorphic methods. The view here is on the implementation. In C# (and all other statically typed languages that I know that support functions), functions are polymorphic based on signature.

A consumer that depends on a function with the type Func<Foo, Qux, Corge, Bar> can interact with any function with that type.

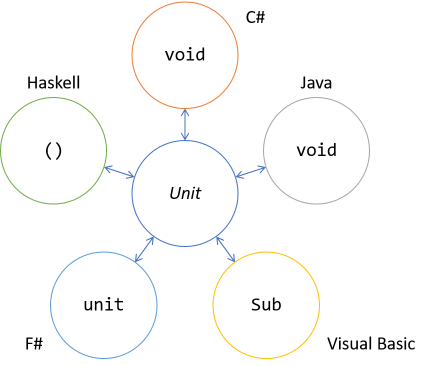

Unit isomorphisms

The C# and Java keyword 'void' is isomorphic to a data type called 'unit'.

This article is part of a series of articles about software design isomorphisms.

Many programming languages, such as C# and Java, distinguish between methods that return something, and methods that don't return anything. In C# and Java, a method must be declared with a return type, but if it doesn't return anything, you can use the special keyword void to indicate that this is the case:

public void Foo(int bar)

This is a C# example, but it would look similar (isomorphic?) in Java.

Two kinds of methods #

In C# and Java, void isn't a type, but a keyword. This means that there are two distinct types of methods:

- Methods that return something

- Methods that return nothing

public Foo Bar(Baz baz, Qux qux)

On the other hand, methods that return nothing must use the special void keyword:

public void Bar(Baz baz, Qux qux)

If you want to generalise, you can use generics like this:

public T Foo<T, T1, T2>(T1 x, T2 y)

Such a method could return anything, but, surprisingly, not nothing. In C# and Java, nothing is special. You can't generalise all methods to a common set. Even with generics, you must model methods that return nothing in a different way:

public void Foo<T1, T2>(T1 x, T2 y)

In C#, for example, this leads to the distinction between Func and Action. You can't reconcile these two fundamentally distinct types of methods into one.

Visual Basic .NET makes the same distinction, but uses the keywords Sub and Function instead of void.

Sometimes, particularly when writing code with generics, this dichotomy is really annoying. Wouldn't it be nice to be able to generalise all methods?

Unit #

While I don't recall the source, I've read somewhere the suggestion that the keyword void was chosen to go with null, because null and void is an English (legal) idiom. That choice is, however, unfortunate.

In category theory, the term void denotes a type or set with no inhabitants (e.g. an empty set). That sounds like the same concept. The problem, from a programming perspective, is that if you have a (static) type with no inhabitants, you can't create an instance of it. See Bartosz Milewski's article Types and Functions for a great explanation and more details.

Functional programming languages like F# and Haskell instead model nothing by a type called unit (often rendered as empty brackets: ()). This type is a type with exactly one inhabitant, a bit like a Singleton, but with the extra restriction that the inhabitant carries no information. It simply is.

It may sound strange and counter-intuitive that a singleton value represents nothing, but it turns out that this is, indeed, isomorphic to C# or Java's void.

This is admirably illustrated by F#, which consistently uses unit instead of void. F# is a multi-paradigmatic language, so you can write classes with methods as well as functions:

member this.Bar (x : int) = ()

This Bar method has the return type unit. When you compile F# code, it becomes Intermediate Language, which you can decompile into C#. If you do that, the above F# code becomes:

public void Bar(int x)

The inverse translation works as well. When you use F#'s interoperability features to interact with objects written in C# or Visual Basic, the F# compiler interprets void methods as if they return unit. For example, calling GC.Collect returns unit in F#, although C# sees it as 'returning' void:

> GC.Collect 0;; val it : unit = ()

F#'s unit is isomorphic to C#'s void keyword, but apart from that, there's nothing special about it. It's a value like any other, and can be used in generically typed functions, like the built-in id function:

> id 42;; val it : int = 42 > id "foo";; val it : string = "foo" > id ();; val it : unit = ()

The built-in function id simply returns its input argument. It has the type 'a -> 'a, and as the above F# Interactive session demonstrates, you can call it with unit as well as with int, string, and so on.

Monoid #

Unit, by the way, forms a monoid. This is most evident in Haskell, where this is encoded into the type. In general, a monoid is a binary operation, and not a type, but what could the combination of two () (unit) values be, other than ()?

λ> mempty :: () () λ> mappend () () ()

In fact, the above (rhetorical) question is imprecise, since there aren't two unit values. There's only one, but used twice.

Since only a single unit value exists, any binary operation is automatically associative, because, after all, it can only return unit. Likewise, unit is the identity (mempty) for the operation, because it doesn't change the output. Thus, the monoid laws hold, and unit forms a monoid.

This result is interesting when you start to think about composition, because a monoid can always be used to reduce (aggregate) multiple values to a single value. With this result, and unit isomorphism, we've already explained why Commands are composable.

Summary #

Since unit is a type only inhabited by a single value, people (including me) often use the word unit about both the type and its only value. Normally, the context surrounding such use is enough to dispel any ambiguity.

Unit is isomorphic to C# or Java void. This is an important result, because if we're to study software design and code structure, we don't have to deal with two distinct cases (methods that return nothing, and methods that return something). Instead, we can ignore methods that return nothing, because they can instead be modelled as methods that return unit.

The reason I've titled this article in the plural is that you could view the isomorphism between F# unit and C# void as a different isomorphism than the one between C# and Java void. Add Haskell's () (unit) type and Visual Basic's Sub keyword to the mix, and it should be clear that there are many translations to the category theory concept of Unit.

Unit isomorphism is an example of an interlingual isomorphism, in the sense that C# void maps to F# unit, and vice versa. In the next example, you'll see an isomorphism that mostly stays within a single language, although a translation between languages is also pertinent.

Next: Function isomorphisms.

Software design isomorphisms

When programming, you can often express the same concept in multiple ways. If you can losslessly translate between two alternatives, it's an isomorphism. An introduction for object-oriented programmers.

This article series is part of an even larger series of articles about the relationship between design patterns and category theory.

There's a school of functional programming that looks to category theory for inspiration, verification, abstraction, and cross-pollination of ideas. Perhaps you're put off by terms like zygohistomorphic prepromorphism (a joke), but you shouldn't be. There are often good reasons for using abstract naming. In any case, one term from category theory that occasionally makes the rounds is isomorphism.

Equivalence #

Don't let the terminology daunt you. An isomorphism is an easy enough concept to grasp. In essence, two things are isomorphic if you can translate losslessly back and forth between them. It's a formalisation of equivalence.

Many programming languages, like C# and Java, offer a multitude of alternative ways to do things. Just consider this C# example from my Humane Code video:

public bool IsSatisfiedBy(Customer candidate) { bool retVal; if (candidate.TotalPurchases >= 10000) retVal = true; else retVal = false; return retVal; }

which is equivalent to this:

public bool IsSatisfiedBy(Customer candidate) { return candidate.TotalPurchases >= 10000; }

An outside observer can't tell the difference between these two implementations, because they have exactly the same externally visible behaviour. You can always refactor from one implementation to the other without loss of information. Thus, we could claim that they're isomorphic.

Terminology #

If you're an object-oriented programmer, then you already know the word polymorphism, which sounds similar to isomorphism. Perhaps you've also heard the word xenomorph. It's all Greek. Morph means form or shape, and while poly means many, iso means equal. So isomorphism means 'being of equal shape'.

This is most likely the explanation for the term Isomorphic JavaScript. The people who came up with that term knew (enough) Greek, but apparently not mathematics. In mathematics, and particularly category theory, an isomorphism is a translation with an inverse. That's still not a formal definition, but just my attempt at presenting it without too much jargon.

Category theory uses the word object to describe a member of a category. I'm going to use that terminology here as well, but you should be aware that object doesn't imply object-oriented programming. It just means 'thing', 'item', 'element', 'entity', etcetera.

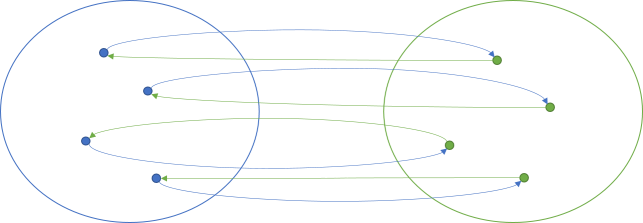

In category theory, a morphism is a mapping or translation of an object to another object. If, for all objects, there's an inverse morphism that leads back to the origin, then it's an isomorphism.

In this illustration, the blue arrows going from left to right indicate a single morphism. It's a mapping of objects on the blue left side to objects on the green right side. The green arrows going from right to left is another morphism. In this case, the green right-to-left morphism is an inverse of the blue left-to-right morphism, because by applying both morphisms, you end where you started. It doesn't matter if you start at the blue left side or the green right side.

Another way to view this is to say that a lossless translation exists. When a translation is lossless, it means that you don't lose information by performing the translation. Since all information is still present after a translation, you can go back to the original representation.

Software design isomorphisms #

When programming, you can often solve the same problem in different ways. Sometimes, the alternatives are isomorphic: you can go back and forth between two alternatives without loss of information.

Martin Fowler's book Refactoring contains several examples. For instance, you can apply Extract Method followed by Inline Method and be back where you started.

There are many other isomorphisms in programming. Some are morphisms in the same language, as is the case with the above C# example. This is also the case with the isomorphisms in Refactoring, because a refactoring, by definition, is a change applied to a particular code base, be it C#, Java, Ruby, or Python.

Other programming isomorphisms go between languages, where a concept can be modelled in one way in, say, C++, but in another way in Clojure. The present blog, for instance, contains several examples of translating between C# and F#, and between F# and Haskell.

Being aware of software design isomorphisms can make you a better programmer. It'll enable you to select the best alternative for solving a particular problem. Identifying programming isomorphisms is also important because it'll enable us to formally think about code structure by reducing many alternative representations to a canonical representation. For these reasons, this article presents a catalogue of software design isomorphisms:

- Unit isomorphisms

- Function isomorphisms