ploeh blog danish software design

The IO Container

How a type system can distinguish between pure and impure code.

Referential transparency is the foundation of functional architecture. If you categorise all operations into pure functions and impure actions, then most other traits associated with functional programming follow.

Unfortunately, mainstream programming languages don't distinguish between pure functions and impure actions. Identifying pure functions is tricky, and the knowledge is fleeting. What was a pure function today may become impure next time someone changes the code.

Separating pure and impure code is important. It'd be nice if you could automate the process. Perhaps you could run some tests, or, even better, make the compiler do the work. That's what Haskell and a few other languages do.

In Haskell, the distinction is made with a container called IO. This static type enforces the functional interaction law at compile time: pure functions can't invoke impure actions.

Opaque container #

Regular readers of this blog know that I often use Haskell to demonstrate principles of functional programming. If you don't know Haskell, however, its ability to guarantee the functional interaction law at compile time may seem magical. It's not.

Fortunately, the design is so simple that it's easy to explain the fundamental concept: Results of impure actions are always enclosed in an opaque container called IO. You can think of it as a box with a label.

The label only tells you about the static type of the value inside the box. It could be an int, a DateTime, or your own custom type, say Reservation. While you know what type of value is inside the box, you can't see what's in it, and you can't open it.

Name #

The container itself is called IO, but don't take the word too literally. While all I/O (input/output) is inherently impure, other operations that you don't typically think of as I/O is impure as well. Generation of random numbers (including GUIDs) is the most prominent example. Random number generators rely on the system clock, which you can think of as an input device, although I think many programmers don't.

I could have called the container Impure instead, but I chose to go with IO, since this is the word used in Haskell. It also has the advantage of being short.

What's in the boooox? #

A question frequently comes up: How do I get the value out of my IO? As always, the answer is mu. You don't. You inject the desired behaviour into the container. This goes for all monads, including IO.

But naturally you wonder: If you can't see the value inside the IO box then what's the point?

The point is to enforce the functional interaction law at the type level. A pure function that calls an impure action will receive a sealed, opaque IO box. There's no API that enables a pure function to extract the contents of the container, so this effectively enforces the rule that pure functions can't call impure actions.

The other three types of interactions are still possible.

- Pure functions should be able to call pure functions. Pure functions return 'normal' values (i.e. values not hidden in IO boxes), so they can call each other as usual.

- Impure actions should be able to call pure functions. This becomes possible because you can inject pure behaviour into any monad. You'll see example of that in later articles in this series.

- Impure actions should be able to call other impure actions. Likewise, you can compose many IO actions into one IO action via the IO API.

On the other hand, if you're already inside the box, you can see the contents. And there's one additional rule: If you're already inside an IO box, you can open other IO boxes and see their contents!

In subsequent articles in this article series, you'll see how all of this manifests as C# code. This article gives a high-level view of the concept. I suggest that you go back and re-read it once you've seen the code.

The many-worlds interpretation #

If you're looking for metaphors or other ways to understand what's going on, there's two perspectives I find useful. None of them offer the full picture, but together, I find that they help.

A common interpretation of IO is that it's like the box in which you put Schrödinger's cat. IO<Cat> can be viewed as the superposition of the two states of cat (assuming that Cat is basically a sum type with the cases Alive and Dead). Likewise, IO<int> represents the superposition of all 4,294,967,296 32-bit integers, IO<string> the superposition of infinitely many strings, etcetera.

Only when you observe the contents of the box does the superposition collapse to a single value.

But... you can't observe the contents of an IO box, can you?

The black hole interpretation #

The IO container represents an impenetrable barrier between the outside and the inside. It's like a black hole. Matter can fall into a black hole, but no information can escape its event horizon.

In high school I took cosmology, among many other things. I don't know if the following is still current, but we learned a formula for calculating the density of a black hole, based on its mass. When you input the estimated mass of the universe, the formula suggests a density near vacuum. Wait, what?! Are we actually living inside a black hole? Perhaps. Could there be other universes 'inside' black holes?

The analogy to the IO container seems apt. You can't see into a black hole from the outside, but once beyond the blue event horizon, you can observe everything that goes on in that interior universe. You can't escape to the original universe, though.

As with all metaphors, this one breaks down if you think too much about it. Code running in IO can unpack other IO boxes, even nested boxes. There's no reason to believe that if you're inside a black hole that you can then gaze beyond the event horizon of nested black holes.

Code examples #

In the next articles in this series, you'll see C# code examples that illustrate how this concept might be implemented. The purpose of these code examples is to give you a sense for how IO works in Haskell, but with more familiar syntax.

- IO container in a parallel C# universe

- Syntactic sugar for IO

- Referential transparency of IO

- Implementation of the C# IO container

- Task asynchronous programming as an IO surrogate

Conclusion #

When you saw the title, did you think that this would be an article about IoC Containers? It's not. The title isn't a typo, and I never use the term IoC Container. As Steven and I explain in our book, Inversion of Control (IoC) is a broader concept than Dependency Injection (DI). It's called a DI Container.

IO, on the other hand, is a container of impure values. Its API enables you to 'build' bigger structures (programs) from smaller IO boxes. You can compose IO actions together and inject pure functions into them. The boxes, however, are opaque. Pure functions can't see their contents. This effectively enforces the functional interaction law at the type level.

Retiring old service versions

A few ideas on how to retire old versions of a web service.

I was recently listening to a .NET Rocks! episode on web APIs, and one of the topics that came up was how to retire old versions of a web service. It's not easy to do, but not necessarily impossible.

The best approach to API versioning is to never break compatibility. As long as there's no breaking changes, you don't have to version your API. It's rarely possible to completely avoid breaking changes, but the fewer of those that you introduce, the fewer API version you have to maintain. I've previously described how to version REST APIs, but this article doesn't assume any particular versioning strategy.

Sooner or later you'll have an old version that you'd like to retire. How do you do that?

Incentives #

First, take a minute to understand why some clients keep using old versions of your API. It may be obvious, but I meet enough programmers who never give incentives a thought that I find it worthwhile to point out.

When you introduce a breaking change, by definition this is a change that breaks clients. Thus, upgrading from an old version to a newer version of your API is likely to give client developers extra work. If what they have already works to their satisfaction, why should they upgrade their clients?

You might argue that your new version is 'better' because it has more features, or is faster, or whatever it is that makes it better. Still, if the old version is good enough for a particular purpose, some clients are going to stay there. The client maintainers have no incentives to upgrade. There's only cost, and no benefit, to upgrading.

Even if the developers who maintain those clients would like to upgrade, they may be prohibited from doing so by their managers. If there's no business reason to upgrade, efforts are better used somewhere else.

Advance warning #

Web services exist in various contexts. Some are only available on an internal network, while others are publicly available on the internet. Some require an authentication token or API key, while others allow anonymous client access.

With some services, you have a way to contact every single client developer. With other services, you don't know who uses your service.

Regardless of the situation, when you wish to retire a version, you should first try to give clients advance warning. If you have an address list of all client developers, you can simply write them all, but you can't expect that everyone reads their mail. If you don't know the clients, you can publish the warning. If you have a blog or a marketing site, you can publish the warning there. If you run a mailing list, you can write about the upcoming change there. You can tweet it, post it on Facebook, or dance it on TikTok.

Depending on SLAs and contracts, there may even be a legally valid communications channel that you can use.

Give advance warning. That's the decent thing to do.

Slow it down #

Even with advance warning, not everyone gets the message. Or, even if everyone got the message, some people deliberately decide to ignore it. Consider their incentives. They may gamble that as long as your logs show that they use the old version, you'll keep it online. What do you do then?

You can, of course, just take the version off line. That's going to break clients that still depend on that version. That's rarely the best course of action.

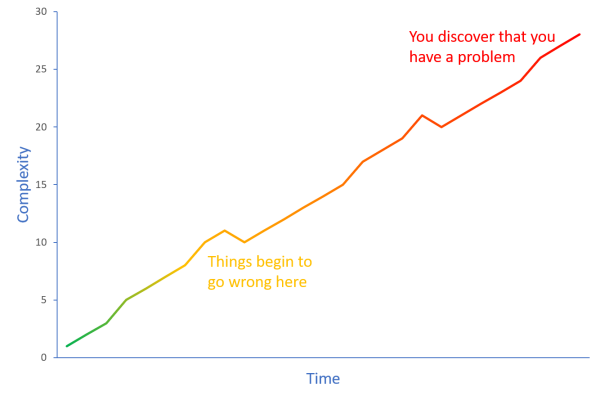

Another option is to degrade the performance of that version. Make it slower. You can simply add a constant delay when clients access that service, or you can gradually degrade performance.

Many HTTP client libraries have long timeouts. For example, the default HttpClient timeout is 100 seconds. Imagine that you want to introduce a gradual performance degradation that starts at no delay on June 1, 2020 and reaches 100 seconds after one year. You can use the formula d = 100 s * (t - t0) / 1 year, where d is the delay, t is the current time, and t0 is the start time (e.g. June 1, 2020). This'll cause requests for resources to gradually slow down. After a year, clients still talking to the retiring version will begin to time out.

You can think of this as another way to give advance warning. With the gradual deterioration of performance, users will likely notice the long wait times well before calls actually time out.

When client developers contact you about the bad performance, you can tell them that the issue is fixed in more recent versions. You've just given the client organisation an incentive to upgrade.

Failure injection #

Another option is to deliberately make the service err now and then. Randomly return a 500 Internal Server Error from time to time, even if the service can handle the request.

Like deliberate performance degradation, you can gradually make the deprecated version more and more unreliable. Again, end users are likely to start complaining about the unreliability of the system long before it becomes entirely useless.

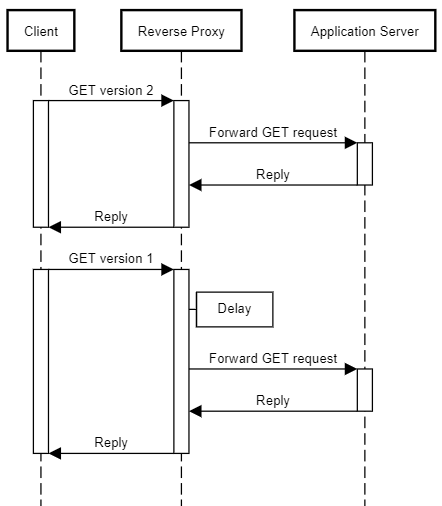

Reverse proxy #

One of the many benefits of HTTP-based services is that you can put a reverse proxy in front of your application servers. I've no idea how to configure or operate NGINX or Varnish, but from talking to people who do know, I get the impression that they're quite scriptable.

Since the above ideas are independent of actual service implementation or behaviour, it's a generic problem that you should seek to address with general-purpose software.

Imagine having a general-purpose reverse proxy that detects whether incoming HTTP requests are for the version you'd like to retire (version 1 in the diagram) or another version. If the proxy detects that the request is for a retiring version, it inserts a delay before it forward the request to the application server. For all requests for current versions, it just forwards the request.

I could imagine doing something similar with failure injections.

Legal ramifications #

All of the above are only ideas. If you can use them, great. Consider the implications, though. You may be legally obliged to keep an SLA. In that case, you can't degrade the performance or reliability below the SLA level.

In any case, I don't think you should do any of these things lightly. Involve relevant stakeholders before you engage in something like the above.

Legal specialists are as careful and conservative as traditional operations teams. Their default reaction to any change proposal is to say no. That's not a judgement on their character or morals, but simply another observation based on incentives. As long as everything works as it's supposed to work, any change represents a risk. Legal specialists, like operations teams, are typically embedded in incentive systems that punish risk-taking.

To counter other stakeholders' reluctance to engage in unorthodox behaviour, you'll have to explain why retiring an old version of the service is important. It works best if you can quantify the reason. If you can, measure how much extra time you waste on maintaining the old version. If the old version runs on separate hardware, or a separate cloud service, quantify the cost overhead.

If you can't produce a compelling argument to retire an old version, then perhaps it isn't that important after all.

Logs #

Server logs can be useful. They can tell you how many requests the old version serves, which IP addresses they come from, at which times or dates you have most traffic, and whether the usage trend is increasing or decreasing.

These measures can be used to support your argument that a particular version should be retired.

Conclusion #

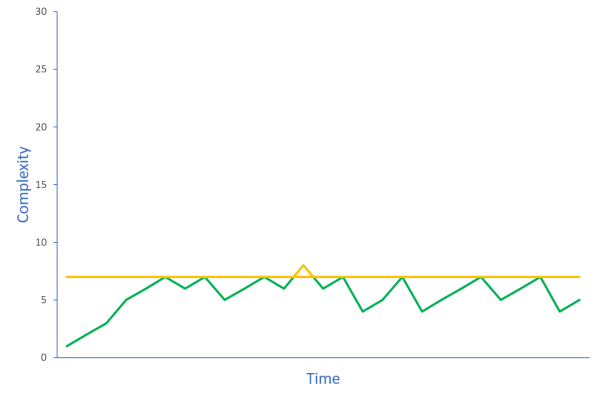

Versioning web services is already a complex subject, but once you've figured it out, you'll sooner or later want to retire an old version of your API. If some clients still make good use of that version, you'll have to give them incentive to upgrade to a newer version.

It's best if you can proactively make clients migrate, so prioritise amiable solutions. Sometimes, however, you have no way to reach all client developers, or no obvious way to motivate them to upgrade. In those cases, gentle and gradual performance or reliability degradation of deprecated versions could be a way.

I present these ideas as nothing more than that: ideas. Use them if they make sense in your context, but think things through. The responsibility is yours.

Comments

Hi Mark. As always an excellent piece. A few comments if I may.

An assumption seems to be, that the client is able to update to a new version of the API, but is not inclined to do so for various reasons. I work with organisations where updating a client if nearly impossible. Not because of lack of will, but due to other factors such as government regulations, physical location of client, hardware version or capabilities of said client to name just a few.

We have a tendency in the software industry to see updates as a question of 'running Windows update' and then all is good. Most likely because that is the world we live in. If we wish to update a program or even an OS, it is fairly easy even your above considerations taken into account.

In the 'physical' world of manufacturing (or pharmacy or mining or ...) the situation is different. The lifetime of the 'thing' running the client is regularly measured in years or even decades and not weeks or months as it is for a piece of software.

Updates are often equal to bloating of resource requirements meaning you have to replace the hardware. This might not always be possible again for various reasons. Cost (company is pressed on margin or client is located in Outer Mongolia) or risk (client is located in Syria or some other hotspot) are some I've personally come across.

REST/HTTP is not used. I acknowledge that the original podcast from .NET Rocks! was about updating a web service. This does not change the premises of your arguments, but it potentially adds a layer of complication.

Karsten, thank you for writing. You are correct that the underlying assumption is that you can retire old versions.

I, too, have written REST APIs where retiring service versions weren't an option. These were APIs that consumer-grade hardware would communicate with. We had no way to assure that consumers would upgrade their hardware. Those boxes wouldn't have much of a user-interface. Owners might not realise that firmware updates were available, even if they were.

This article does, indeed, assume that the reader has made an informed decision that it's fundamentally acceptable to retire a service version. I should have made that more explicit.

Where's the science?

Is a scientific discussion about software development possible?

Have you ever found yourself in a heated discussion about a software development topic? Which is best? Tabs or spaces? Where do you put the curly brackets? Is significant whitespace a good idea? Is Python better than Go? Does test-driven development yield an advantage? Is there a silver bullet? Can you measure software development productivity?

I've had plenty of such discussions, and I'll have them again in the future.

While some of these discussions may resemble debates on how many angels can dance on the head of a pin, other discussions might be important. Ex ante, it's hard to tell which is which.

Why don't we settle these discussions with science?

A notion of science #

I love science. Why don't I apply scientific knowledge instead of arguments based on anecdotal evidence?

To answer such questions, we must first agree on a definition of science. I favour Karl Popper's description of empirical falsifiability. A hypothesis that makes successful falsifiable predictions of the future is a good scientific theory. Such a a theory has predictive power.

Newton's theory of gravity had ample predictive power, but Einstein's theory of general relativity supplanted it because its predictive power was even better.

Mendel's theory of inheritance had predictive power, but was refined into what is modern-day genetics which yields much greater predictive power.

Is predictive power the only distinguishing trait of good science? I'm already venturing into controversial territory by taking this position. I've met people in the programming community who consider my position naive or reductionist.

What about explanatory power? If a theory satisfactorily explains observed phenomena, doesn't that count as a proper scientific theory?

Controversy #

I don't believe in explanatory power as a sufficient criterion for science. Without predictive power, we have little evidence that an explanation is correct. An explanatory theory can even be internally consistent, and yet we may not know if it describes reality.

Theories with explanatory power are the realm of politics or religion. Consider the observation that some people are rich and some are poor. You can believe in a theory that explains this by claiming structural societal oppression. You can believe in another theory that views poor people as fundamentally lazy. Both are (somewhat internally consistent) political theories, but they have yet to demonstrate much predictive power.

Likewise, you may believe that some deity created the universe, but that belief produces no predictions. You can apply Occam's razor and explain the same phenomena without a god. A belief in one or more gods is a religious theory, not a scientific theory.

It seems to me that there's a correlation between explanatory power and controversy. Over time, theories with predictive power become uncontroversial. Even if they start out controversial (such as Einstein's theory of general relativity), the dust soon settles because it's hard to argue with results.

Theories with mere explanatory power, on the other hand, can fuel controversy forever. Explanations can be compelling, and without evidence to refute them, the theories linger.

Ironically, you might argue that Popper's theory of scientific discovery itself is controversial. It's a great explanation, but does it have predictive power? Not much, I admit, but I'm also not aware of competing views on science with better predictive power. Thus, you're free to disagree with everything in this article. I admit that it's a piece of philosophy, not of science.

The practicality of experimental verification #

We typically see our field of software development as one of the pillars of STEM. Many of us have STEM educations (I don't; I'm an economist). Yet, we're struggling to come to grips with the lack of scientific methodology in our field. It seems to me that we suffer from physics envy.

It's really hard to compete with physics when it comes to predictive power, but even modern physics struggle with experimental verification. Consider an establishment like CERN. It takes billions of euros of investment to make today's physics experiments possible. The only reason we make such investments, I think, is that physics so far has had a good track record.

What about another fairly 'hard' science like medicine? In order to produce proper falsifiable predictions, medical science have evolved the process of the randomised controlled trial. It works well when you're studying short-term effects. Does this medicine cure this disease? Does this surgical procedure improve a patient's condition? How does lack of REM sleep for three days affect your ability to remember strings of numbers?

When a doctor tells you that a particular medicine helps, or that surgery might be warranted, he or she is typically on solid scientific grounds.

Here's where things start to become less clear, though, What if a doctor tells you that a particular diet will improve your expected life span? Is he or she on scientific solid ground?

That's rarely the case, because you can't make randomised controlled trials about life styles. Or, rather, a totalitarian society might be able to do that, but we'd consider it unethical. Consider what it would involve: You'd have to randomly select a significant number of babies and group them into those who must follow a particular life style, and those who must not. Then you'll somehow have to force those people to stick to their randomly assigned life style for the entirety of their lives. This is not only unethical, but the experiment also takes the most of a century to perform.

What life-style scientists instead do is resort to demographic studies, with all the problems of statistics they involve. Again, the question is whether scientific theories in this field offer predictive power. Perhaps they do, but it takes decades to evaluate the results.

My point is that medicine isn't exclusively a hard science. Some medicine is, and some is closer to social sciences.

I'm an economist by education. Economics is generally not considered a hard science, although it's a field where it's trivial to make falsifiable predictions. Almost all of economics is about numbers, so making a falsifiable prediction is trivial: The MSFT stock will be at 200 by January 1 2021. The unemployment rate in Denmark will be below 5% in third quarter of 2020. The problem with economics is that most of such predictions turn out to be no better than the toss of a coin - even when made by economists. You can make falsifiable predictions in economics, but most of them do, in fact, get falsified.

On the other hand, with the advances in such disparate fields as DNA forensics, satellite surveys, and computer-aided image processing, a venerable 'art' like archaeology is gaining predictive power. We predict that if we dig here, we'll find artefacts from the iron age. We predict that if we make a DNA test of these skeletal remains, they'll show that the person buried was a middle-aged women. And so on.

One thing is the ability to produce falsifiable predictions. Another things is whether or not the associated experiment is practically possible.

The science of software development #

Do we have a science of software development? I don't think that we have.

There's computer science, but that's not quite the same. That field of study has produced many predictions that hold. In general, quicksort will be faster than bubble sort. There's an algorithm for finding the shortest way through a network. That sort of thing.

You will notice that these result are hardly controversial. It's not those topics that we endlessly debate.

We debate whether certain ways to organise work is more 'productive'. The entire productivity debate revolves around an often implicit context: that what we discuss is long-term productivity. We don't much argue how to throw together something during a weekend hackaton. We argue whether we can complete a nine-month software project safer with test-driven development. We argue whether a code base can better sustain its organisation year after year if it's written in F# or JavaScript.

There's little scientific evidence on those questions.

The main problem, as I see it, is that it's impractical to perform experiments. Coming up with falsifiable predictions is easy.

Let's consider an example. Imagine that your hypothesis is that test-driven development makes you more productive in the middle and long run. You'll have to turn that into a falsifiable claim, so first, pick a software development project of sufficient complexity. Imagine that you can find a project that someone estimates will take around ten months to complete for a team of five people. This has to be a real project that someone needs done, complete with vague, contradictory, and changing requirements. Now you formulate your falsifiable prediction, for example: "This project will be delivered one month earlier with test-driven development."

Next, you form teams to undertake the work. One team to perform the work with test-driven development, and one team to do the work without it. Then you measure when they're done.

This is already impractical, because who's going to pay for two teams when one would suffice?

Perhaps, if you're an exceptional proposal writer, you could get a research grant for that, but alas, that wouldn't be good enough.

With two competing teams of five people each, it might happen that one team member exhibits productivity orders of magnitudes different from the others. That could skew the experimental outcome, so you'd have to go for a proper randomised controlled trial. This would involve picking numerous teams and assigning a methodology at random: either they do test-driven development, or they don't. Nothing else should vary. They should all use the same programming language, the same libraries, the same development tools, and work the same hours. Furthermore, no-one outside the team should know which teams follow which method.

Theoretically possible, but impractical. It would require finding and paying many software teams for most of a year. One such experiment would cost millions of euros.

If you did such an experiment, it would tell you something, but it'd still be open to interpretation. You might argue that the programming language used caused the outcome, but that one can't extrapolate from that result to other languages. Or perhaps there was something special about the project that you think doesn't generalise. Or perhaps you take issue with the pool from which the team members were drawn. You'd have to repeat the experiment while varying one of the other dimensions. That'll cost millions more, and take another year.

Considering the billions of euros/dollars/pounds the world's governments pour into research, you'd think that we could divert a few hundred millions to do proper research in software development, but it's unlikely to happen. That's the reason we have to contend ourselves with arguing from anecdotal evidence.

Conclusion #

I can imagine how scientific inquiry into software engineering could work. It'd involve making a falsifiable prediction, and then set up an experiment to prove it wrong. Unfortunately, to be on a scientifically sound footing, experiments should be performed with randomised controlled trials, with a statistically significant number of participants. It's not too hard to conceive of such experiments, but they'd be prohibitively expensive.

In the meantime, the software development industry moves forward. We share ideas and copy each other. Some of us are successful, and some of us fail. Slowly, this might lead to improvements.

That process, however, looks more like evolution than scientific progress. The fittest software development organisations survive. They need not be the best, as they could be stuck in local maxima.

When we argue, when we write blog posts, when we speak at conferences, when we appear on podcasts, we exchange ideas and experiences. Not genes, but memes.

Comments

That topic is something many software developers think about, at least I do from time to time.

Your post reminded me of that conference talk Intro to Empirical Software Engineering: What We Know We Don't Know by Hillel Wayne. Just curious - have you seen the talk and if so - what do you think? Researches mentioned in the talk are not proper scientific expreiments as you describe, but anyway looked really interesting to me.

Sergey, thank you for writing. I didn't know about that talk, but Hillel Wayne regularly makes an appearance in my Twitter feed. I've now seen the talk, and I think it offers a perspective close to mine.

I've already read The Leprechauns of Software Engineering (above, I linked to my review), but while I was aware of Making Software, I've yet to read it. Several people have reacted to my article by recommending that book, so it's now on it's way to me in the mail.

Modelling versus shaping reality

How does software development relate to reality?

I recently appeared as a guest on the .NET Rocks! podcast where we discussed Fred Brooks' 1986 essay No Silver Bullet. As a reaction, Jon Suda wrote a thoughtful piece of his own. That made me think some more.

Beware of Greeks... #

Brooks' central premise is Aristotle's distinction between essential and accidental complexity. I've already examined the argument in my previous article on the topic, but in summary, Brooks posits that complexity in software development can be separated into those two categories:

c = E + a

Here, c is the total complexity, E is the essential complexity, and a the accidental complexity. I've deliberately represented c and a with lower-case letters to suggest that they represent variables, whereas I mean to suggest with the upper-case E that the essential complexity is constant. That's Brooks' argument: Every problem has an essential complexity that can't be changed. Thus, your only chance to reduce total complexity c is to reduce the accidental complexity a.

Jon Suda writes that

That got me thinking, because actually I do. When I wrote Yes silver bullet I wanted to engage with Brooks' essay on its own terms."Mark doesn’t disagree with the classification of problems"

I do think, however, that one should be sceptical of any argument originating from the ancient Greeks. These people believed that all matter was composed of earth, water, air, and fire. They believed in the extramission theory of vision. They practised medicine by trying to balance blood, phlegm, yellow, and black bile. Aristotle believed in spontaneous generation. He also believed that the brain was a radiator while the heart was the seat of intelligence.

I think that Aristotle's distinction between essential and accidental complexity is a false dichotomy, at least in the realm of software development.

The problem is the assumption that there's a single, immutable underlying reality to be modelled.

Modelling reality #

Jon Suda touches on this as well:

I agree that the 'real world' (whatever it is) is often messy, and our ability to deal with the mess is how we earn our keep. It seems to me, though, that there's an underlying assumption that there's a single real world to be modelled."Conceptual (or business) problems are rooted in the problem domain (i.e., the real world)[...]"

"Dealing with the "messy real world" is what makes software development hard these days"

I think that a more fruitful perspective is to question that assumption. Don’t try to model the real world, it doesn’t exist.

I've mostly worked with business software. Web shops, BLOBAs, and other software to support business endeavours. This is the realm implicitly addressed by Domain-Driven Design and a technique like behaviour-driven development. The assumption is that there's one or more domain experts who know how the business operates, and the job of the software development team is to translate that understanding into working software.

This is often the way it happens. Lord knows that I've been involved in enough fixed-requirements contracts to know that sometimes, all you can do is try to implement the requirements as best you can, regardless of how messy they are. In other words, I agree with Jon Suda that messy problems are a reality.

Where I disagree with Brooks and Aristotle is that business processes contain essential complexity. In the old days, before computers, businesses ran according to a set of written and unwritten rules. Routine operations might be fairly consistent, but occasionally, something out of the ordinary would happen. Organisations don't have a script for every eventuality. When the unexpected happens, people wing it.

A business may have a way it sells its goods. It may have a standard price list, and a set of discounts that salespeople are authorised to offer. It may have standard payment terms that customers are expected to comply with. It may even have standard operating procedures for dealing with missing payments.

Then one day, say, the German government expresses interest in placing an order greater than the business has ever handled before. The Germans, however, want a special discount, and special terms of payment. What happens? Do the salespeople refuse because those requests don't comply with the way the organisation does business? Of course not. The case is escalated to people with the authority to change the rules, and a deal is made.

Later, the French government comes by, and a similar situation unfolds, but with the difference that someone else handles the French, and the deal struck is different.

The way these two cases are handled could be internally inconsistent. Decisions are made based on concrete contexts, but with incomplete information and based on gut feelings.

While there may be a system to how an organisation does routine business, there's no uniform reality to be modelled.

You can model standard operating procedures in software, but I think it's a mistake to think that it's a model of reality. It's just an interpretation on how routine business is conducted.

There's no single, unyielding essential complexity, because the essence isn't there.

Shaping reality #

Dan North tells a story of a project where a core business requirement was the ability to print out data. When investigating the issue, it turned out that users needed to have the printout next to their computers so that they could type the data into another system. When asked whether they wouldn't rather prefer to have the data just appear in the other system, they incredulously replied, "You can do that?!

This turns out to be a common experience. Someone may tell you about an essential requirement, but when you investigate, it turns out to be not at all essential. There may not be any essential complexity.

There's likely to be complexity, but the distinction between essential and accidental complexity seems artificial. While software can model business processes, it can also shape reality. Consider a company like Amazon. The software that supports Amazon wasn't developed after the company was already established. Amazon developed it concurrently with setting up business.

Consider companies like Google, Facebook, Uber, or Airbnb. Such software doesn't model reality; it shapes reality.

In the beginning of the IT revolution, the driving force behind business software development was to automate existing real-world processes, but this is becoming increasingly rare. New companies enter the markets digitally born. Older organisations may be on their second or third system since they went digital. Software not only models 'messy' reality - it shapes 'messy' reality.

Conclusion #

It may look as though I fundamentally disagree with Jon Suda's blog post. I don't. I agree with almost all of it. It did, however, inspire me to put my thoughts into writing.

My position is that I find the situation more nuanced than Fred Brooks suggests by setting off from Aristotle. I don't think that the distinction between essential and accidental complexity is the whole story. Granted, it provides a fruitful and inspiring perspective, but while we find it insightful, we shouldn't accept it as gospel.

Comments

I think I agree with virtually everything said here – if not actually everything 😊

As (virtually, if not actually) always, though, there are a few things I’d like to add, clarify, and elaborate on 😊

I fully share your reluctance to accept ancient Greek philosophy. I once discussed No Silver Bullet (and drank Scotch) with a (non-developer) “philosopher” friend of mine. (Understand: He has a BA in philosophy 😊) He said something to the effect of do you understand this essence/accident theory is considered obsolete? I answered that it was beside the point here – at least as far as I was concerned. For me, the dichotomy serves as an inspiration, a metaphor perhaps, not a rigorous theoretical framework – that’s one of the reasons why I adapted it into the (informal) conceptual/technical distinction.

I also 100% agree with the notion that software shouldn’t merely “model” or “automate” reality. In fact, I now remember that back in university, this was one of the central themes of my “thesis” (or whatever it was). I pondered the difference/boundary between analysis and design activities and concluded that the idea of creating a model of the “real world” during analysis and then building a technical representation of this model as part of design/implementation couldn’t adequately describe many of the more “inventive” software projects and products.

I don’t, however, believe this makes the conceptual/technical (essential/accidental) distinction go away. Even though the point of a project may not (and should not) be a mere automation of a preexisting reality, you still need to know what you want to achieve (i.e., “invent”), conceptually, to be able to fashion a technical implementation of it. And yes, your conceptual model should be based on what’s possible with all available technology – which is why you’ll hopefully end up with something way better than the old solution. (Note that in my post, I never talk about “modeling” the “messy real world” but rather “dealing with it”; even your revolutionary new solution will have to coexist with the messy outside world.)

For me, one of the main lessons of No Silver Bullet, the moral of the story, is this: Developers tend to spend inordinate amounts of time discussing and brooding over geeky technical stuff; perhaps they should, instead, talk to their users a bit more and learn something about the problem domain; that’s where the biggest room for improvement is, in my opinion.

FWIW

https://jonsmusings.com/Transmutation-of-Reality

Let the inspiration feedback loop continue 😊 I agree with more-or-less everything you say; I just don’t necessarily think that your ideas are incompatible with those expressed in No Silver Bullet. That, to a significant extent (but not exclusively), is what my new post is about. As I said in my previous comment, your article reminded me of my university “thesis,” and I felt that the paper I used as its “conceptual framework” was worth presenting in a “non-academic” form. It can mostly be used to support your arguments – I certainly use it that way.

AFK

Software development productivity tip: regularly step away from the computer.

In these days of covid-19, people are learning that productivity is imperfectly correlated to the amount of time one is physically present in an office. Indeed, the time you spend in front of you computer is hardly correlated to your productivity. After all, programming productivity isn't measured by typing speed. Additionally, you can waste much time at the computer, checking Twitter, watching cat videos on YouTube, etc.

Pomodorobut #

I've worked from home for years, so I thought I'd share some productivity tips. I only report what works for me. If you can use some of the tips, then great. If they're not for you, that's okay too. I don't pretend that I've found any secret sauce or universal truth.

A major problem with productivity is finding the discipline to work. I use Pomodorobut. It's like Scrumbut, but for the Pomodoro technique. For years I thought I was using the Pomodoro technique, but Arialdo Martini makes a compelling case that I'm not. He suggests just calling it timeboxing.

I think it's a little more than that, though, because the way I use Pomodorobut has two equally important components:

- The 25-minute work period

- The 5-minute break

When you program, you often run into problems:

- There's a bug that you don't understand.

- You can't figure out the correct algorithm to implement a particular behaviour.

- Your code doesn't compile, and you don't understand why.

- A framework behaves inexplicably.

The solution: take a break.

Breaks give a fresh perspective #

I take my Pomodorobut breaks seriously. My rule is that I must leave my office during the break. I usually go get a glass of water or the like. The point is to get out of the chair and afk (away from keyboard).

While I'm out the room, it often happens that I get an insight. If I'm stuck on something, I may think of a potential solution, or I may realise that the problem is irrelevant, because of a wider context I forgot about when I sat in front of the computer.

You may have heard about rubber ducking. Ostensibly

I've tried it enough times: you ask a colleague if he or she has a minute, launch into an explanation of your problem, only to break halfway through and say: "Never mind! I suddenly realised what the problem is. Thank you for your help.""By having to verbalize [...], you may suddenly gain new insight into the problem."

Working from home, I haven't had a colleague I could disturb like that for years, and I don't actually use a rubber duck. In my experience, getting out of my chair works equally well.

The Pomodorobut technique makes me productive because the breaks, and the insights they spark, reduce the time I waste on knotty problems. When I'm in danger of becoming stuck, I often find a way forward in less than 30 minutes: at most 25 minutes being stuck, and a 5-minute break to get unstuck.

Hammock-driven development #

Working from home gives you extra flexibility. I have a regular routine where I go for a run around 10 in the morning. I also routinely go grocery shopping around 14 in the afternoon. Years ago, when I still worked in an office, I'd ride my bicycle to and from work every day. I've had my good ideas during those activities.

In fact, I can't recall ever having had a profound insight in front of the computer. They always come to me when I'm away from it. For instance, I distinctly remember walking around in my apartment doing other things when I realised that the Visitor design pattern is just another encoding of a sum type.

Insights don't come for free. As Rich Hickey points out in his talk about hammock-driven development, you must feed your 'background mind'. That involves deliberate focus on the problem.

Good ideas don't come if you're permanently away from the computer, but neither do they arrive if all you do is stare at the screen. It's the variety that makes you productive.

Conclusion #

Software development productivity is weakly correlated with the time you spend in front of the computer. I find that I'm most productive when I can vary my activities during the day. Do a few 25-minute sessions, rigidly interrupted by breaks. Go for a run. Work a bit more on the computer. Have lunch. Do one or two more time-boxed sessions. Go grocery shopping. Conclude with a final pair of work sessions.

Significant whitespace is DRY

Languages with explicit scoping encourage you to repeat yourself.

When the talk falls on significant whitespace, the most common reaction I hear seems to be one of nervous apotropaic deflection.

I've always wondered why people react like that. What's the problem with significant whitespace?"Indentation matters? Oh, no! I'm horrified."

If given a choice, I'd prefer indentation to matter. In that way, I don't have to declare scope more than once.

Explicit scope #

If you had to choose between the following three C# implementations of the FizzBuzz kata, which one would you choose?

a:

class Program { static void Main() { for (int i = 1; i < 100; i++) { if (i % 15 == 0) { Console.WriteLine("FizzBuzz"); } else if (i % 3 == 0) { Console.WriteLine("Fizz"); } else if (i % 5 == 0) { Console.WriteLine("Buzz"); } else { Console.WriteLine(i); } } } }

b:

class Program { static void Main() { for (int i = 1; i < 100; i++) { if (i % 15 == 0) { Console.WriteLine("FizzBuzz"); } else if (i % 3 == 0) { Console.WriteLine("Fizz"); } else if (i % 5 == 0) { Console.WriteLine("Buzz"); } else { Console.WriteLine(i); } } } }

c:

class Program { static void Main() { for (int i = 1; i < 100; i++) { if (i % 15 == 0) { Console.WriteLine("FizzBuzz"); } else if (i % 3 == 0) { Console.WriteLine("Fizz"); } else if (i % 5 == 0) { Console.WriteLine("Buzz"); } else { Console.WriteLine(i); } } } }

Which of these do you prefer? a, b, or c?

You prefer b. Everyone does.

Yet, those three examples are equivalent. Not only do they behave the same - except for whitespace, they're identical. They produce the same effective abstract syntax tree.

Even though a language like C# has explicit scoping and statement termination with its curly brackets and semicolons, indentation still matters. It doesn't matter to the compiler, but it matters to humans.

When you format code like option b, you express scope twice. Once for the compiler, and once for human readers. You're repeating yourself.

Significant whitespace #

Some languages dispense with the ceremony and let indentation indicate scope. The most prominent is Python, but I've more experience with F# and Haskell. In F#, you could write FizzBuzz like this:

[<EntryPoint>] let main argv = for i in [1..100] do if i % 15 = 0 then printfn "FizzBuzz" else if i % 3 = 0 then printfn "Fizz" else if i % 5 = 0 then printfn "Buzz" else printfn "%i" i 0

You don't have to explicitly scope variables or expressions. The scope is automatically indicated by the indentation. You don't repeat yourself. Scope is expressed once, and both compiler and human understand it.

I've programmed in F# for a decade now, and I don't find its use of significant whitespace to be a problem. I'd recommend, however, to turn on the feature in your IDE of choice that shows whitespace characters.

Summary #

Significant whitespace is a good language feature. You're going to indent your code anyway, so why not let the indentation carry meaning? In that way, you don't repeat yourself.

An F# implementation of the Maître d' kata

This article walks you through the Maître d' kata done in F#.

In a previous article, I presented the Maître d' kata and promised to publish a walkthrough. Here it is.

Preparation #

I used test-driven development and F# for both unit tests and implementation. As usual, my test framework was xUnit.net (2.4.0) with Unquote (5.0.0) as the assertion library.

I could have done the exercise with a property-based testing framework like FsCheck or Hedgehog, but I chose instead to take my own medicine. In the kata description, I suggested some test cases, so I wanted to try and see if they made sense.

The entire code base is available on GitHub.

Boutique restaurant #

I wrote the first suggested test case this way:

[<Fact>]

let ``Boutique restaurant`` () =

test <@ canAccept 12 [] { Quantity = 1 } @>

This uses Unquote's test function to verify that a Boolean expression is true. The expression is a function call to canAccept with the capacity 12, no existing reservations, and a reservation with Quantity = 1.

The simplest thing that could possibly work was this:

type Reservation = { Quantity : int } let canAccept _ _ _ = true

The Reservation type was required to make the test compile, but the canAccept function didn't have to consider its arguments. It could simply return true.

Parametrisation #

The next test case made me turn the test function into a parametrised test:

[<Theory>] [<InlineData( 1, true)>] [<InlineData(13, false)>] let ``Boutique restaurant`` quantity expected = expected =! canAccept 12 [] { Quantity = quantity }

So far, the only test parameters were quantity and the expected result. I could no longer use test to verify the result of calling canAccept, since I added variation to the expected result. I changed test into Unquote's =! (must equal) operator.

The simplest passing implementation I could think of was:

let canAccept _ _ { Quantity = q } = q = 1

It ignored the capacity and instead checked whether q is 1. That passed both tests.

Test data API #

Before adding another test case, I decided to refactor my test code a bit. When working with a real domain model, you often have to furnish test data in order to make code compile - even if that data isn't relevant to the test. I wanted to demonstrate how to deal with this issue. My first step was to introduce an 'arbitrary' Reservation value in the spirit of Test data without Builders.

let aReservation = { Quantity = 1 }

This enabled me to rewrite the test:

[<Theory>] [<InlineData( 1, true)>] [<InlineData(13, false)>] let ``Boutique restaurant`` quantity expected = expected =! canAccept 12 [] { aReservation with Quantity = quantity }

This doesn't look like an immediate improvement, but it made it possible to make the Reservation record type more realistic without damage to the test:

type Reservation = {

Date : DateTime

Name : string

Email : string

Quantity : int }

I added some fields that a real-world reservation would have. The Quantity field will be useful later on, but the Name and Email fields are irrelevant in the context of the kata.

This is the type of API change that often gives people grief. To create a Reservation value, you must supply all four fields. This often adds noise to tests.

Not here, though, because the only concession I had to make was to change aReservation:

let aReservation = { Date = DateTime (2019, 11, 29, 12, 0, 0) Name = "" Email = "" Quantity = 1 }

The test code remained unaltered.

With that in place, I could add the third test case:

[<Theory>] [<InlineData( 1, true)>] [<InlineData(13, false)>] [<InlineData(12, true)>] let ``Boutique restaurant`` quantity expected = expected =! canAccept 12 [] { aReservation with Quantity = quantity }

The simplest passing implementation I could think of was:

let canAccept _ _ { Quantity = q } = q <> 13

This implementation still ignored the restaurant's capacity and simply checked that q was different from 13. That was enough to pass all three tests.

Refactor test case code #

Adding the next suggested test case proved to be a problem. I wanted to write a single [<Theory>]-driven test function fed by all the Boutique restaurant test data. To do that, I'd have to supply arrays of test input, but unfortunately, that wasn't possible in F#.

Instead I decided to refactor the test case code to use ClassData-driven test cases.

type BoutiqueTestCases () as this = inherit TheoryData<int, bool> () do this.Add ( 1, true) this.Add (13, false) this.Add (12, true) [<Theory; ClassData(typeof<BoutiqueTestCases>)>] let ``Boutique restaurant`` quantity expected = expected =! canAccept 12 [] { aReservation with Quantity = quantity }

These are the same test cases as before, but now expressed by a class inheriting from TheoryData<int, bool>. The implementing code remains the same.

Existing reservation #

The next suggested test case includes an existing reservation. To support that, I changed the test case base class to TheoryData<int, int list, int, bool>, and passed empty lists for the first three test cases. For the new, fourth test case, I supplied a number of seats.

type BoutiqueTestCases () as this = inherit TheoryData<int, int list, int, bool> () do this.Add (12, [], 1, true) this.Add (12, [], 13, false) this.Add (12, [], 12, true) this.Add ( 4, [2], 3, false) [<Theory; ClassData(typeof<BoutiqueTestCases>)>] let ``Boutique restaurant`` capacity reservatedSeats quantity expected = let rs = List.map (fun s -> { aReservation with Quantity = s }) reservatedSeats let actual = canAccept capacity rs { aReservation with Quantity = quantity } expected =! actual

This also forced me to to change the body of the test function. At this stage, it could be prettier, but it got the job done. I soon after improved it.

My implementation, as usual, was the simplest thing that could possibly work.

let canAccept _ reservations { Quantity = q } =

q <> 13 && Seq.isEmpty reservations

Notice that although the fourth test case varied the capacity, I still managed to pass all tests without looking at it.

Accept despite existing reservation #

The next test case introduced another existing reservation, but this time with enough capacity to accept a new reservation.

type BoutiqueTestCases () as this = inherit TheoryData<int, int list, int, bool> () do this.Add (12, [], 1, true) this.Add (12, [], 13, false) this.Add (12, [], 12, true) this.Add ( 4, [2], 3, false) this.Add (10, [2], 3, true)

The test function remained unchanged.

In the spirit of the Devil's advocate technique, I actively sought to avoid a correct implementation. I came up with this:

let canAccept capacity reservations { Quantity = q } = let reservedSeats = match Seq.tryHead reservations with | Some r -> r.Quantity | None -> 0 reservedSeats + q <= capacity

Since all test cases supplied at most one existing reservation, it was enough to consider the first reservation, if present.

To many people, it may seem strange to actively seek out incorrect implementations like this. An incorrect implementation that passes all tests does, however, demonstrate the need for more tests.

The sum of all reservations #

I then added another test case, this time with three existing reservations:

type BoutiqueTestCases () as this = inherit TheoryData<int, int list, int, bool> () do this.Add (12, [], 1, true) this.Add (12, [], 13, false) this.Add (12, [], 12, true) this.Add ( 4, [2], 3, false) this.Add (10, [2], 3, true) this.Add (10, [3;2;3], 3, false)

Again, I left the test function untouched.

On the side of the implementation, I couldn't think of more hoops to jump through, so I finally gave in and provided a 'proper' implementation:

let canAccept capacity reservations { Quantity = q } = let reservedSeats = Seq.sumBy (fun r -> r.Quantity) reservations reservedSeats + q <= capacity

Not only does it look simpler that before, but I also felt that the implementation was warranted.

Although I'd only tested“As the tests get more specific, the code gets more generic.”

canAccept with lists, I decided to implement it with Seq. This was a decision I later regretted.

Another date #

The last Boutique restaurant test case was to supply an existing reservation on another date. The canAccept function should only consider existing reservations on the date in question.

First, I decided to model the two separate dates as two values:

let d1 = DateTime (2023, 9, 14) let d2 = DateTime (2023, 9, 15)

I hoped that it would make my test cases more readable, because the dates would have a denser representation.

type BoutiqueTestCases () as this = inherit TheoryData<int, (int * DateTime) list, (int * DateTime), bool> () do this.Add (12, [], ( 1, d1), true) this.Add (12, [], (13, d1), false) this.Add (12, [], (12, d1), true) this.Add ( 4, [(2, d1)], ( 3, d1), false) this.Add (10, [(2, d1)], ( 3, d1), true) this.Add (10, [(3, d1);(2, d1);(3, d1)], ( 3, d1), false) this.Add ( 4, [(2, d2)], ( 3, d1), true)

I changed the representation of a reservation from just an int to a tuple of a number and a date. I also got tired of looking at that noisy unit test, so I introduced a test-specific helper function:

let reserve (q, d) = { aReservation with Quantity = q; Date = d }

Since it takes a tuple of a number and a date, I could use it to simplify the test function:

[<Theory; ClassData(typeof<BoutiqueTestCases>)>] let ``Boutique restaurant`` (capacity, rs, r, expected) = let reservations = List.map reserve rs let actual = canAccept capacity reservations (reserve r) expected =! actual

The canAccept function now had to filter the reservations on Date:

let canAccept capacity reservations { Quantity = q; Date = d } = let relevantReservations = Seq.filter (fun r -> r.Date = d) reservations let reservedSeats = Seq.sumBy (fun r -> r.Quantity) relevantReservations reservedSeats + q <= capacity

This implementation specifically compared dates, though, so while it passed all tests, it'd behave incorrectly if the dates were as much as nanosecond off. That implied that another test case was required.

Same date, different time #

The final test case for the Boutique restaurant, then, was to use two DateTime values on the same date, but with different times.

type BoutiqueTestCases () as this = inherit TheoryData<int, (int * DateTime) list, (int * DateTime), bool> () do this.Add (12, [], ( 1, d1 ), true) this.Add (12, [], (13, d1 ), false) this.Add (12, [], (12, d1 ), true) this.Add ( 4, [(2, d1)], ( 3, d1 ), false) this.Add (10, [(2, d1)], ( 3, d1 ), true) this.Add (10, [(3, d1);(2, d1);(3, d1)], ( 3, d1 ), false) this.Add ( 4, [(2, d2)], ( 3, d1 ), true) this.Add ( 4, [(2, d1)], ( 3, d1.AddHours 1.), false)

I just added a new test case as a new line and lined up the data. The test function, again, didn't change.

To address the new test case, I generalised the first filter.

let canAccept capacity reservations { Quantity = q; Date = d } = let relevantReservations = Seq.filter (fun r -> r.Date.Date = d.Date) reservations let reservedSeats = Seq.sumBy (fun r -> r.Quantity) relevantReservations reservedSeats + q <= capacity

An expression like r.Date.Date looks a little odd. DateTime values have a Date property that represents its date part. The first Date is the Reservation field, and the second is the date part.

I was now content with the Boutique restaurant implementation.

Haute cuisine #

In the next phase of the kata, I now had to deal with a configuration of more than one table, so I introduced a type:

type Table = { Seats : int }

It's really only a glorified wrapper around an int, but with a real domain model in place, I could make its constructor private and instead afford a smart constructor that only accepts positive integers.

I changed the canAccept function to take a list of tables, instead of capacity. This also required me to change the existing test function to take a singleton list of tables:

let actual = canAccept [table capacity] reservations (reserve r)

where table is a test-specific helper function:

let table s = { Seats = s }

I also added a new test function and a single test case:

let d3 = DateTime (2024, 6, 7) type HauteCuisineTestCases () as this = inherit TheoryData<int list, (int * DateTime) list, (int * DateTime), bool> () do this.Add ([2;2;4;4], [], (4, d3), true) [<Theory; ClassData(typeof<HauteCuisineTestCases>)>] let ``Haute cuisine`` (tableSeats, rs, r, expected) = let tables = List.map table tableSeats let reservations = List.map reserve rs let actual = canAccept tables reservations (reserve r) expected =! actual

The change to canAccept is modest:

let canAccept tables reservations { Quantity = q; Date = d } = let capacity = Seq.sumBy (fun t -> t.Seats) tables let relevantReservations = Seq.filter (fun r -> r.Date.Date = d.Date) reservations let reservedSeats = Seq.sumBy (fun r -> r.Quantity) relevantReservations reservedSeats + q <= capacity

It still works by looking at a total capacity as if there was just a single communal table. Now it just calculates capacity from the sequence of tables.

Reject reservation that doesn't fit largest table #

Then I added the next test case to the new test function:

type HauteCuisineTestCases () as this = inherit TheoryData<int list, (int * DateTime) list, (int * DateTime), bool> () do this.Add ([2;2;4;4], [], (4, d3), true) this.Add ([2;2;4;4], [], (5, d3), false)

This one attempts to make a reservation for five people. The largest table only fits four people, so this reservation should be rejected. The current implementation just considered the total capacity of all tables, to it accepted the reservation, and thereby failed the test.

This change to canAccept passes all tests:

let canAccept tables reservations { Quantity = q; Date = d } = let capacity = tables |> Seq.map (fun t -> t.Seats) |> Seq.max let relevantReservations = Seq.filter (fun r -> r.Date.Date = d.Date) reservations let reservedSeats = Seq.sumBy (fun r -> r.Quantity) relevantReservations reservedSeats + q <= capacity

The function now only considered the largest table in the restaurant. While it's incorrect to ignore all other tables, all tests passed.

Accept when there's still a remaining table #

Only considering the largest table is obviously wrong, so I added another test case where there's an existing reservation.

type HauteCuisineTestCases () as this = inherit TheoryData<int list, (int * DateTime) list, (int * DateTime), bool> () do this.Add ([2;2;4;4], [], (4, d3), true) this.Add ([2;2;4;4], [], (5, d3), false) this.Add ( [2;2;4], [(2, d3)], (4, d3), true)

While canAccept should accept the reservation, it didn't when I added the test case. In a variation of the Devil's Advocate technique, I came up with this implementation to pass all tests:

let canAccept tables reservations { Quantity = q; Date = d } = let largestTable = tables |> Seq.map (fun t -> t.Seats) |> Seq.max let capacity = tables |> Seq.sumBy (fun t -> t.Seats) let relevantReservations = Seq.filter (fun r -> r.Date.Date = d.Date) reservations let reservedSeats = Seq.sumBy (fun r -> r.Quantity) relevantReservations q <= largestTable && reservedSeats + q <= capacity

This still wasn't the correct implementation. It represented a return to looking at the total capacity of all tables, with the extra rule that you couldn't make a reservation larger than the largest table. At least one more test case was needed.

Accept when remaining table is available #

I added another test case to the haute cuisine test cases. This one came with one existing reservation for three people, effectively reserving the four-person table. While the remaining tables have an aggregate capacity of four, it's two separate tables. Therefore, a reservation for four people should be rejected.

type HauteCuisineTestCases () as this = inherit TheoryData<int list, (int * DateTime) list, (int * DateTime), bool> () do this.Add ([2;2;4;4], [], (4, d3), true) this.Add ([2;2;4;4], [], (5, d3), false) this.Add ( [2;2;4], [(2, d3)], (4, d3), true) this.Add ( [2;2;4], [(3, d3)], (4, d3), false)

It then dawned on me that I had to explicitly distinguish between a communal table configuration, and individual tables that aren't communal, regardless of size. This triggered quite a refactoring.

I defined a new type to distinguish between these two types of table layout:

type TableConfiguration = Communal of int | Tables of Table list

I also had to change the existing test functions, including the boutique restaurant test

[<Theory; ClassData(typeof<BoutiqueTestCases>)>] let ``Boutique restaurant`` (capacity, rs, r, expected) = let reservations = List.map reserve rs let actual = canAccept (Communal capacity) reservations (reserve r) expected =! actual

and the haute cuisine test

[<Theory; ClassData(typeof<HauteCuisineTestCases>)>] let ``Haute cuisine`` (tableSeats, rs, r, expected) = let tables = List.map table tableSeats let reservations = List.map reserve rs let actual = canAccept (Tables tables) reservations (reserve r) expected =! actual

In both cases I had to change the call to canAccept to pass either a Communal or a Tables value.

Delete first #

I'd previously done the kata in Haskell and was able to solve this phase of the kata using the built-in deleteFirstsBy function. This function doesn't exist in the F# core library, so I decided to add it. I created a new module named Seq and first defined a function that deletes the first element that satisfies a predicate:

// ('a -> bool) -> seq<'a> -> seq<'a> let deleteFirstBy pred (xs : _ seq) = seq { let mutable found = false use e = xs.GetEnumerator () while e.MoveNext () do if found then yield e.Current else if pred e.Current then found <- true else yield e.Current }

It moves over a sequence of elements and looks for an element that satisfies pred. If such an element is found, it's omitted from the output sequence. The function only deletes the first occurrence from the sequence, so any other elements that satisfy the predicate are still included.

This function corresponds to Haskell's deleteBy function and can be used to implement deleteFirstsBy:

// ('a -> 'b -> bool) -> seq<'b> -> seq<'a> -> seq<'b> let deleteFirstsBy pred = Seq.fold (fun xs x -> deleteFirstBy (pred x) xs)

As the Haskell documentation explains, the "deleteFirstsBy function takes a predicate and two lists and returns the first list with the first occurrence of each element of the second list removed." My F# function does the same, but works on sequences instead of linked lists.

I could use it to find and remove tables that were already reserved.

Find remaining tables #

I first defined a little helper function to determine whether a table can accommodate a reservation:

// Reservation -> Table -> bool let private fits r t = r.Quantity <= t.Seats

The rule is simply that the table's number of Seats must be greater than or equal to the reservation's Quantity. I could use this function for the predicate for Seq.deleteFirstsBy:

let canAccept config reservations ({ Quantity = q; Date = d } as r) = let contemporaneousReservations = Seq.filter (fun r -> r.Date.Date = d.Date) reservations match config with | Communal capacity -> let reservedSeats = Seq.sumBy (fun r -> r.Quantity) contemporaneousReservations reservedSeats + q <= capacity | Tables tables -> let rs = Seq.sort contemporaneousReservations let remainingTables = Seq.deleteFirstsBy fits (Seq.sort tables) rs Seq.exists (fits r) remainingTables

The canAccept function now branched on Communal versus Tables configurations. In the Communal configuration, it simply compared the reservedSeats and reservation quantity to the communal table's capacity.

In the Tables case, the function used Seq.deleteFirstsBy fits to remove all the tables that are already reserved. The result is the remainingTables. If there exists a remaining table that fits the reservation, then the function accepts the reservation.

This seemed to me an appropriate implementation of the haute cuisine phase of the kata.

Second seatings #

Now it was time to take seating duration into account. While I could have written my test cases directly against the TimeSpan API, I didn't want to write TimeSpan.FromHours 2.5, TimeSpan.FromDays 1., and so on. I found that it made my test cases harder to read, so I added some literal extensions:

type Int32 with member x.hours = TimeSpan.FromHours (float x) member x.days = TimeSpan.FromDays (float x)

This enabled me to write expressions like 1 .days and 2 .hours, as shown in the first test case:

let d4 = DateTime (2023, 10, 22, 18, 0, 0) type SecondSeatingsTestCases () as this = inherit TheoryData<TimeSpan, int list, (int * DateTime) list, (int * DateTime), bool> () do this.Add (2 .hours, [2;2;4], [(4, d4)], (3, d4.Add (2 .hours)), true)

I used this initial parametrised test case for a new test function:

[<Theory; ClassData(typeof<SecondSeatingsTestCases>)>] let ``Second seatings`` (dur, tableSeats, rs, r, expected) = let tables = List.map table tableSeats let reservations = List.map reserve rs let actual = canAccept dur (Tables tables) reservations (reserve r) expected =! actual

My motivation for this test case was mostly to introduce an API change to canAccept. I didn't want to rock the boat too much, so I picked a test case that wouldn't trigger a big change to the implementation. I prefer incremental changes. The only change is the introduction of the seatingDur argument:

let canAccept (seatingDur : TimeSpan) config reservations ({ Date = d } as r) = let contemporaneousReservations = Seq.filter (fun x -> x.Date.Subtract seatingDur < d.Date) reservations match config with | Communal capacity -> let reservedSeats = Seq.sumBy (fun r -> r.Quantity) contemporaneousReservations reservedSeats + r.Quantity <= capacity | Tables tables -> let rs = Seq.sort contemporaneousReservations let remainingTables = Seq.deleteFirstsBy fits (Seq.sort tables) rs Seq.exists (fits r) remainingTables

While the function already considered seatingDur, the way it filtered reservation wasn't entirely correct. It passed all tests, though.

Filter reservations based on seating duration #

The next test case I added made me write what I consider the right implementation, but I subsequently decided to add two more test cases just for confidence. Here's all of them:

type SecondSeatingsTestCases () as this = inherit TheoryData<TimeSpan, int list, (int * DateTime) list, (int * DateTime), bool> () do this.Add ( 2 .hours, [2;2;4], [(4, d4)], (3, d4.Add (2 .hours)), true) this.Add ( 2.5 .hours, [2;4;4], [(2, d4);(1, d4.AddMinutes 15.);(2, d4.Subtract (15 .minutes))], (3, d4.AddHours 2.), false) this.Add ( 2.5 .hours, [2;4;4], [(2, d4);(2, d4.Subtract (15 .minutes))], (3, d4.AddHours 2.), true) this.Add ( 2.5 .hours, [2;4;4], [(2, d4);(1, d4.AddMinutes 15.);(2, d4.Subtract (15 .minutes))], (3, d4.AddHours 2.25), true)

The new test cases use some more literal extensions:

type Int32 with member x.minutes = TimeSpan.FromMinutes (float x) member x.hours = TimeSpan.FromHours (float x) member x.days = TimeSpan.FromDays (float x) type Double with member x.hours = TimeSpan.FromHours x

I added a private isContemporaneous function to the code base and used it to filter the reservation to pass the tests:

let private isContemporaneous (seatingDur : TimeSpan) (candidate : Reservation) (existing : Reservation) = let aSeatingBefore = candidate.Date.Subtract seatingDur let aSeatingAfter = candidate.Date.Add seatingDur aSeatingBefore < existing.Date && existing.Date < aSeatingAfter let canAccept (seatingDur : TimeSpan) config reservations r = let contemporaneousReservations = Seq.filter (isContemporaneous seatingDur r) reservations match config with | Communal capacity -> let reservedSeats = Seq.sumBy (fun r -> r.Quantity) contemporaneousReservations reservedSeats + r.Quantity <= capacity | Tables tables -> let rs = Seq.sort contemporaneousReservations let remainingTables = Seq.deleteFirstsBy fits (Seq.sort tables) rs Seq.exists (fits r) remainingTables

I could have left the functionality of isContemporaneous inside of canAccept, but I found it just hard enough to get my head around that I preferred to put it in a named helper function. Checking that a value is in a range is in itself trivial, but for some reason, figuring out the limits of the range didn't come naturally to me.

This version of canAccept only considered existing reservations if they in any way overlapped with the reservation in question. It passed all tests. It also seemed to me to be a satisfactory implementation of the second seatings scenario.

Alternative table configurations #

This state of the kata introduces groups of tables that can be reserved individually, or combined. To support that, I changed the definition of Table:

type Table = Discrete of int | Group of int list

A Table is now either a Discrete table that can't be combined, or a Group of tables that can either be reserved individually, or combined.

I had to change the test-specific table function to behave like before.

let table s = Discrete s

Before this change to the Table type, all tables were implicitly Discrete tables.

This enabled me to add the first test case:

type AlternativeTableConfigurationTestCases () as this = inherit TheoryData<Table list, int list, int, bool> () do this.Add ( [Discrete 4; Discrete 1; Discrete 2; Group [2;2;2]], [3;1;2], 2, true) [<Theory; ClassData(typeof<AlternativeTableConfigurationTestCases>)>] let ``Alternative table configurations`` (tables, rs, r, expected) = let res i = reserve (i, d4) let reservations = List.map res rs let actual = canAccept (1 .days) (Tables tables) reservations (res r) expected =! actual

Like I did when I introduced the seatingDur argument, I deliberately chose a test case that didn't otherwise rock the boat too much. The same was the case now, so the only other change I had to make to pass all tests was to adjust the fits function:

// Reservation -> Table -> bool let private fits r = function | Discrete seats -> r.Quantity <= seats | Group _ -> true

It's clearly not correct to return true for any Group, but it passed all tests.

Accept based on sum of table group #

I wanted to edge a little closer to correctly handling the Group case, so I added a test case:

type AlternativeTableConfigurationTestCases () as this = inherit TheoryData<Table list, int list, int, bool> () do this.Add ( [Discrete 4; Discrete 1; Discrete 2; Group [2;2;2]], [3;1;2], 2, true) this.Add ( [Discrete 4; Discrete 1; Discrete 2; Group [2;2;2]], [3;1;2], 7, false)

A restaurant with this table configuration can't accept a reservation for seven people, but because fits returned true for any Group, canAccept would return true. Since the test expected the result to be false, this caused the test to fail.

Edging closer to correct behaviour, I adjusted fits again:

// Reservation -> Table -> bool let private fits r = function | Discrete seats -> r.Quantity <= seats | Group tables -> r.Quantity <= List.sum tables

This was still not correct, because it removed an entire group of tables when fits returned true, but it passed all tests so far.

Accept reservation by combining two tables #

I added another failing test:

type AlternativeTableConfigurationTestCases () as this = inherit TheoryData<Table list, int list, int, bool> () do this.Add ( [Discrete 4; Discrete 1; Discrete 2; Group [2;2;2]], [3;1;2], 2, true) this.Add ( [Discrete 4; Discrete 1; Discrete 2; Group [2;2;2]], [3;1;2], 7, false) this.Add ( [Discrete 4; Discrete 1; Discrete 2; Group [2;2;2]], [3;1;2;1], 4, true)

The last test case failed because the existing reservations should only have reserved one of the tables in the group, but because of the way fits worked, the entire group was deleted by Seq.deleteFirstsBy fits. This made canAccept reject the four-person reservation.

To be honest, this step was difficult for me. I should probably have found out how to make a smaller step.

I wanted a function that would compare a Reservation to a Table, but unlike Fits return None if it decided to 'use' the table, or a Some value if it decided that it didn't need to use the entire table. This would enable me to pick only some of the tables from a Group, but still return a Some value with the rest of tables.

I couldn't figure out an elegant way to do this with the existing Seq functionality, so I started to play around with something more specific. The implementation came accidentally as I was struggling to come up with something more general. As I was experimenting, all of a sudden, all tests passed!