ploeh blog danish software design

Either catamorphism

The catamorphism for Either is a generalisation of its fold. The catamorphism enables operations not available via fold.

This article is part of an article series about catamorphisms. A catamorphism is a universal abstraction that describes how to digest a data structure into a potentially more compact value.

This article presents the catamorphism for Either (also known as Result), as well as how to identify it. The beginning of this article presents the catamorphism in C#, with examples. The rest of the article describes how to deduce the catamorphism. This part of the article presents my work in Haskell. Readers not comfortable with Haskell can just read the first part, and consider the rest of the article as an optional appendix.

Either is a data container that models two mutually exclusive results. It's often used to return values that may be either correct (right), or incorrect (left). In statically typed functional programming with a preference for total functions, Either offers a saner, more reasonable way to model success and error results than throwing exceptions.

C# catamorphism #

This article uses the Church encoding of Either. The catamorphism for Either is the Match method:

T Match<T>(Func<L, T> onLeft, Func<R, T> onRight);

Until this article, all previous catamorphisms have been a pair made from an initial value and a function. The Either catamorphism is a generalisation, since it's a pair of functions. One function handles the case where there's a left value, and the other function handles the case where there's a right value. Both functions must return the same, unifying type, which is often a string or something similar that can be shown in a user interface:

> IEither<TimeSpan, int> e = new Left<TimeSpan, int>(TimeSpan.FromMinutes(3)); > e.Match(ts => ts.ToString(), i => i.ToString()) "00:03:00" > IEither<TimeSpan, int> e = new Right<TimeSpan, int>(42); > e.Match(ts => ts.ToString(), i => i.ToString()) "42"

You'll often see examples like the above that turns both left and right cases into strings or something that can be represented as a unifying response type, but this is in no way required. If you can come up with a unifying type, you can convert both cases to that type:

> IEither<Guid, string> e = new Left<Guid, string>(Guid.NewGuid()); > e.Match(g => g.ToString().Count(c => 'a' <= c), s => s.Length) 12 > IEither<Guid, string> e = new Right<Guid, string>("foo"); > e.Match(g => g.ToString().Count(c => 'a' <= c), s => s.Length) 3

In the two above examples, you use two different functions that both reduce respectively Guid and string values to a number. The function that turns Guid values into a number counts how many of the hexadecimal digits that are greater than or equal to A (10). The other function simply returns the length of the string, if it's there. That example makes little sense, but the Match method doesn't care about that.

In practical use, Either is often used for error handling. The article on the Church encoding of Either contains an example.

Either F-Algebra #

As in the previous article, I'll use Fix and cata as explained in Bartosz Milewski's excellent article on F-Algebras.

While F-Algebras and fixed points are mostly used for recursive data structures, you can also define an F-Algebra for a non-recursive data structure. You already saw an example of that in the articles about Boolean catamorphism and Maybe catamorphism. The difference between e.g. Maybe values and Either is that both cases of Either carry a value. You can model this as a Functor with both a carrier type and two type arguments for the data that Either may contain:

data EitherF l r c = LeftF l | RightF r deriving (Show, Eq, Read) instance Functor (EitherF l r) where fmap _ (LeftF l) = LeftF l fmap _ (RightF r) = RightF r

I chose to call the 'data types' l (for left) and r (for right), and the carrier type c (for carrier). As was also the case with BoolF and MaybeF, the Functor instance ignores the map function because the carrier type is missing from both the LeftF case and the RightF case. Like the Functor instances for BoolF and MaybeF, it'd seem that nothing happens, but at the type level, this is still a translation from EitherF l r c to EitherF l r c1. Not much of a function, perhaps, but definitely an endofunctor.

As was also the case when deducing the Maybe and List catamorphisms, Haskell isn't too happy about defining instances for a type like Fix (EitherF l r). To address that problem, you can introduce a newtype wrapper:

newtype EitherFix l r = EitherFix { unEitherFix :: Fix (EitherF l r) } deriving (Show, Eq, Read)

You can define Functor, Applicative, Monad, etc. instances for this type without resorting to any funky GHC extensions. Keep in mind that ultimately, the purpose of all this code is just to figure out what the catamorphism looks like. This code isn't intended for actual use.

A pair of helper functions make it easier to define EitherFix values:

leftF :: l -> EitherFix l r leftF = EitherFix . Fix . LeftF rightF :: r -> EitherFix l r rightF = EitherFix . Fix . RightF

With those functions, you can create EitherFix values:

Prelude Data.UUID Data.UUID.V4 Fix Either> leftF <$> nextRandom

EitherFix {unEitherFix = Fix (LeftF e65378c2-0d6e-47e0-8bcb-7cc29d185fad)}

Prelude Data.UUID Data.UUID.V4 Fix Either> rightF "foo"

EitherFix {unEitherFix = Fix (RightF "foo")}

That's all you need to identify the catamorphism.

Haskell catamorphism #

At this point, you have two out of three elements of an F-Algebra. You have an endofunctor (EitherF l r), and an object c, but you still need to find a morphism EitherF l r c -> c. Notice that the algebra you have to find is the function that reduces the functor to its carrier type c, not the 'data types' l and r. This takes some time to get used to, but that's how catamorphisms work. This doesn't mean, however, that you get to ignore l and r, as you'll see.

As in the previous articles, start by writing a function that will become the catamorphism, based on cata:

eitherF = cata alg . unEitherFix where alg (LeftF l) = undefined alg (RightF r) = undefined

While this compiles, with its undefined implementations, it obviously doesn't do anything useful. I find, however, that it helps me think. How can you return a value of the type c from the LeftF case? You could pass an argument to the eitherF function:

eitherF fl = cata alg . unEitherFix where alg (LeftF l) = fl l alg (RightF r) = undefined

While you could, technically, pass an argument of the type c to eitherF and then return that value from the LeftF case, that would mean that you would ignore the l value. This would be incorrect, so instead, make the argument a function and call it with l. Likewise, you can deal with the RightF case in the same way:

eitherF :: (l -> c) -> (r -> c) -> EitherFix l r -> c eitherF fl fr = cata alg . unEitherFix where alg (LeftF l) = fl l alg (RightF r) = fr r

This works. Since cata has the type Functor f => (f a -> a) -> Fix f -> a, that means that alg has the type f a -> a. In the case of EitherF, the compiler infers that the alg function has the type EitherF l r c -> c, which is just what you need!

You can now see what the carrier type c is for. It's the type that the algebra extracts, and thus the type that the catamorphism returns.

This, then, is the catamorphism for Either. As has been consistent so far, it's a pair, but now made from two functions. As you've seen repeatedly, this isn't the only possible catamorphism, since you can, for example, trivially flip the arguments to eitherF.

I've chosen the representation shown here because it's isomorphic to the either function from Haskell's built-in Data.Either module, which calls the function the "Case analysis for the Either type". Both of these functions (eitherF and either) are equivalent to the above C# Match method.

Basis #

You can implement most other useful functionality with eitherF. Here's the Bifunctor instance:

instance Bifunctor EitherFix where bimap f s = eitherF (leftF . f) (rightF . s)

From that instance, the Functor instance trivially follows:

instance Functor (EitherFix l) where fmap = second

On top of Functor you can add Applicative:

instance Applicative (EitherFix l) where pure = rightF f <*> x = eitherF leftF (<$> x) f

Notice that the <*> implementation is similar to to the <*> implementation for MaybeFix. The same is the case for the Monad instance:

instance Monad (EitherFix l) where x >>= f = eitherF leftF f x

Not only is EitherFix Foldable, it's Bifoldable:

instance Bifoldable EitherFix where bifoldMap = eitherF

Notice, interestingly, that bifoldMap is identical to eitherF.

The Bifoldable instance enables you to trivially implement the Foldable instance:

instance Foldable (EitherFix l) where foldMap = bifoldMap mempty

You may find the presence of mempty puzzling, since bifoldMap (or eitherF; they're identical) takes as arguments two functions. Is mempty a function?

Yes, mempty can be a function. Here, it is. There's a Monoid instance for any function a -> m, where m is a Monoid instance, and mempty is the identity for that monoid. That's the instance in use here.

Just as EitherFix is Bifoldable, it's also Bitraversable:

instance Bitraversable EitherFix where bitraverse fl fr = eitherF (fmap leftF . fl) (fmap rightF . fr)

You can comfortably implement the Traversable instance based on the Bitraversable instance:

instance Traversable (EitherFix l) where sequenceA = bisequenceA . first pure

Finally, you can implement conversions to and from the standard Either type, using ana as the dual of cata:

toEither :: EitherFix l r -> Either l r toEither = eitherF Left Right fromEither :: Either a b -> EitherFix a b fromEither = EitherFix . ana coalg where coalg (Left l) = LeftF l coalg (Right r) = RightF r

This demonstrates that EitherFix is isomorphic to Either, which again establishes that eitherF and either are equivalent.

Relationships #

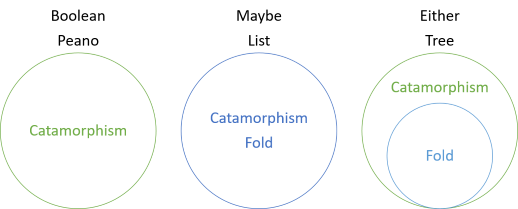

In this series, you've seen various examples of catamorphisms of structures that have no folds, catamorphisms that coincide with folds, and now a catamorphism that is more general than the fold. The introduction to the series included this diagram:

This shows that Boolean values and Peano numbers have catamorphisms, but no folds, whereas for Maybe and List, the fold and the catamorphism is the same. For Either, however, the fold is a special case of the catamorphism. The fold for Either 'pretends' that the left side doesn't exist. Instead, the left value is interpreted as a missing right value. Thus, in order to fold Either values, you must supply a 'fallback' value that will be used in case an Either value isn't a right value:

Prelude Fix Either> e = rightF LT :: EitherFix Integer Ordering Prelude Fix Either> foldr (const . show) "" e "LT" Prelude Fix Either> e = leftF 42 :: EitherFix Integer Ordering Prelude Fix Either> foldr (const . show) "" e ""

In a GHCi session like the above, you can create two Either values of the same type. The right case is an Ordering value, while the left case is an Integer value.

With foldr, there's no way to access the left case. While you can access and transform the right Ordering value, the number 42 is simply ignored during the fold. Instead, the default value "" is returned.

Contrast this with the catamorphism, which can access both cases:

Prelude Fix Either> e = rightF LT :: EitherFix Integer Ordering Prelude Fix Either> eitherF show show e "LT" Prelude Fix Either> e = leftF 42 :: EitherFix Integer Ordering Prelude Fix Either> eitherF show show e "42"

In a session like this, you recreate the same values, but using the catamorphism eitherF, you can now access and transform both the left and the right cases. In other words, the catamorphism enables you to perform operations not possible with the fold.

It's interesting, however, to note that while the fold is a specialisation of the catamorphism, the bifold is identical to the catamorphism.

Summary #

The catamorphism for Either is a pair of functions. One function transforms the left case, while the other function transforms the right case. For any Either value, only one of those functions will be used.

When I originally encountered the concept of a catamorphism, I found it difficult to distinguish between catamorphism and fold. My problem was, I think, that the tutorials I ran into mostly used linked lists to demonstrate how, in that case, the fold is the catamorphism. It turns out, however, that this isn't always the case. A catamorphism is a general abstraction. A fold, on the other hand, seems to me to be mostly related to collections.

In this article you saw the first example of a catamorphism that can do more than the fold. For Either, the fold is just a special case of the catamorphism. You also saw, however, how the catamorphism was identical to the bifold. Thus, it's still not entirely clear how these concepts relate. Therefore, in the next article, you'll get an example of a container where there's no bifold, and where the catamorphism is, indeed, a generalisation of the fold.

Next: Tree catamorphism.

List catamorphism

The catamorphism for a list is the same as its fold.

This article is part of an article series about catamorphisms. A catamorphism is a universal abstraction that describes how to digest a data structure into a potentially more compact value.

This article presents the catamorphism for (linked) lists, and other collections in general. It also shows how to identify it. The beginning of this article presents the catamorphism in C#, with an example. The rest of the article describes how to deduce the catamorphism. This part of the article presents my work in Haskell. Readers not comfortable with Haskell can just read the first part, and consider the rest of the article as an optional appendix.

The C# part of the article will discuss IEnumerable<T>, while the Haskell part will deal specifically with linked lists. Since C# is a less strict language anyway, we have to make some concessions when we consider how concepts translate. In my experience, the functionality of IEnumerable<T> closely mirrors that of Haskell lists.

C# catamorphism #

The .NET base class library defines this Aggregate overload:

public static TAccumulate Aggregate<TSource, TAccumulate>( this IEnumerable<TSource> source, TAccumulate seed, Func<TAccumulate, TSource, TAccumulate> func);

This is the catamorphism for linked lists (and, I'll conjecture, for IEnumerable<T> in general). The introductory article already used it to show several motivating examples, of which I'll only repeat the last:

> new[] { 42, 1337, 2112, 90125, 5040, 7, 1984 } . .Aggregate(Angle.Identity, (a, i) => a.Add(Angle.FromDegrees(i))) [{ Angle = 207° }]

In short, the catamorphism is, similar to the previous catamorphisms covered in this article series, a pair made from an initial value and a function. This has been true for both the Peano catamorphism and the Maybe catamorphism. An initial value is just a value in all three cases, but you may notice that the function in question becomes increasingly elaborate. For IEnumerable<T>, it's a function that takes two values. One of the values are of the type of the input list, i.e. for IEnumerable<TSource> it would be TSource. By elimination you can deduce that this value must come from the input list. The other value is of the type TAccumulate, which implies that it could be the seed, or the result from a previous call to func.

List F-Algebra #

As in the previous article, I'll use Fix and cata as explained in Bartosz Milewski's excellent article on F-Algebras. The ListF type comes from his article as well, although I've renamed the type arguments:

data ListF a c = NilF | ConsF a c deriving (Show, Eq, Read) instance Functor (ListF a) where fmap _ NilF = NilF fmap f (ConsF a c) = ConsF a $ f c

Like I did with MaybeF, I've named the 'data' type argument a, and the carrier type c (for carrier). Once again, notice that the Functor instance maps over the carrier type c; not over the 'data' type a.

As was also the case when deducing the Maybe catamorphism, Haskell isn't too happy about defining instances for a type like Fix (ListF a). To address that problem, you can introduce a newtype wrapper:

newtype ListFix a = ListFix { unListFix :: Fix (ListF a) } deriving (Show, Eq, Read)

You can define Functor, Applicative, Monad, etc. instances for this type without resorting to any funky GHC extensions. Keep in mind that ultimately, the purpose of all this code is just to figure out what the catamorphism looks like. This code isn't intended for actual use.

A few helper functions make it easier to define ListFix values:

nilF :: ListFix a nilF = ListFix $ Fix NilF consF :: a -> ListFix a -> ListFix a consF x = ListFix . Fix . ConsF x . unListFix

With those functions, you can create ListFix linked lists:

Prelude Fix List> nilF

ListFix {unListFix = Fix NilF}

Prelude Fix List> consF 42 $ consF 1337 $ consF 2112 nilF

ListFix {unListFix = Fix (ConsF 42 (Fix (ConsF 1337 (Fix (ConsF 2112 (Fix NilF))))))}

The first example creates an empty list, whereas the second creates a list of three integers, corresponding to [42,1337,2112].

That's all you need to identify the catamorphism.

Haskell catamorphism #

At this point, you have two out of three elements of an F-Algebra. You have an endofunctor (ListF), and an object a, but you still need to find a morphism ListF a c -> c. Notice that the algebra you have to find is the function that reduces the functor to its carrier type c, not the 'data type' a. This takes some time to get used to, but that's how catamorphisms work. This doesn't mean, however, that you get to ignore a, as you'll see.

As in the previous article, start by writing a function that will become the catamorphism, based on cata:

listF = cata alg . unListFix where alg NilF = undefined alg (ConsF h t) = undefined

While this compiles, with its undefined implementations, it obviously doesn't do anything useful. I find, however, that it helps me think. How can you return a value of the type c from the NilF case? You could pass an argument to the listF function:

listF n = cata alg . unListFix where alg NilF = n alg (ConsF h t) = undefined

The ConsF case, contrary to NilF, contains both a head h (of type a) and a tail t (of type c). While you could make the code compile by simply returning t, it'd be incorrect to ignore h. In order to deal with both, you'll need a function that turns both h and t into a value of the type c. You can do this by passing a function to listF and using it:

listF :: (a -> c -> c) -> c -> ListFix a -> c listF f n = cata alg . unListFix where alg NilF = n alg (ConsF h t) = f h t

This works. Since cata has the type Functor f => (f a -> a) -> Fix f -> a, that means that alg has the type f a -> a. In the case of ListF, the compiler infers that the alg function has the type ListF a c -> c, which is just what you need!

You can now see what the carrier type c is for. It's the type that the algebra extracts, and thus the type that the catamorphism returns.

This, then, is the catamorphism for lists. As has been consistent so far, it's a pair made from an initial value and a function. Once more, this isn't the only possible catamorphism, since you can, for example, trivially flip the arguments to listF:

listF :: c -> (a -> c -> c) -> ListFix a -> c listF n f = cata alg . unListFix where alg NilF = n alg (ConsF h t) = f h t

You can also flip the arguments of f:

listF :: c -> (c -> a -> c) -> ListFix a -> c listF n f = cata alg . unListFix where alg NilF = n alg (ConsF h t) = f t h

These representations are all isomorphic to each other, but notice that the last variation is similar to the above C# Aggregate overload. The initial n value is the seed, and the function f has the same shape as func. Thus, I consider it reasonable to conjecture that that Aggregate overload is the catamorphism for IEnumerable<T>.

Basis #

You can implement most other useful functionality with listF. The rest of this article uses the first of the variations shown above, with the type (a -> c -> c) -> c -> ListFix a -> c. Here's the Semigroup instance:

instance Semigroup (ListFix a) where xs <> ys = listF consF ys xs

The initial value passed to listF is ys, and the function to apply is simply the consF function, thus 'consing' the two lists together. Here's an example of the operation in action:

Prelude Fix List> consF 42 $ consF 1337 nilF <> (consF 2112 $ consF 1 nilF)

ListFix {unListFix = Fix (ConsF 42 (Fix (ConsF 1337 (Fix (ConsF 2112 (Fix (ConsF 1 (Fix NilF))))))))}

With a Semigroup instance, it's trivial to also implement the Monoid instance:

instance Monoid (ListFix a) where mempty = nilF

While you could implement mempty with listF (mempty = listF (const id) nilF nilF), that'd be overcomplicated. Just because you can implement all functionality using listF, it doesn't mean that you should, if a simpler alternative exists.

You can, on the other hand, use listF for the Functor instance:

instance Functor ListFix where fmap f = listF (\h l -> consF (f h) l) nilF

You could write the function you pass to listF in a point-free fashion as consF . f, but I thought it'd be easier to follow what happens when written as an explicit lambda expression. The function receives a 'current value' h, as well as the part of the list which has already been translated l. Use f to translate h, and consF the result unto l.

You can add Applicative and Monad instances in a similar fashion:

instance Applicative ListFix where pure x = consF x nilF fs <*> xs = listF (\f acc -> (f <$> xs) <> acc) nilF fs instance Monad ListFix where xs >>= f = listF (\x acc -> f x <> acc) nilF xs

What may be more interesting, however, is the Foldable instance:

instance Foldable ListFix where foldr = listF

The demonstrates that listF and foldr is the same.

Next, you can also add a Traversable instance:

instance Traversable ListFix where sequenceA = listF (\x acc -> consF <$> x <*> acc) (pure nilF)

Finally, you can implement conversions to and from the standard list [] type, using ana as the dual of cata:

toList :: ListFix a -> [a] toList = listF (:) [] fromList :: [a] -> ListFix a fromList = ListFix . ana coalg where coalg [] = NilF coalg (h:t) = ConsF h t

This demonstrates that ListFix is isomorphic to [], which again establishes that listF and foldr are equivalent.

Summary #

The catamorphism for lists is a pair made from an initial value and a function. One variation is equal to foldr. Like Maybe, the catamorphism is the same as the fold.

In C#, this function corresponds to the Aggregate extension method identified above.

You've now seen two examples where the catamorphism coincides with the fold. You've also seen examples (Boolean catamorphism and Peano catamorphism) where there's a catamorphism, but no fold at all. In a subsequent article, you'll see an example of a container that has both catamorphism and fold, but where the catamorphism is more general than the fold.

Next: NonEmpty catamorphism.

Maybe catamorphism

The catamorphism for Maybe is just a simplification of its fold.

This article is part of an article series about catamorphisms. A catamorphism is a universal abstraction that describes how to digest a data structure into a potentially more compact value.

This article presents the catamorphism for Maybe, as well as how to identify it. The beginning of this article presents the catamorphism in C#, with examples. The rest of the article describes how to deduce the catamorphism. This part of the article presents my work in Haskell. Readers not comfortable with Haskell can just read the first part, and consider the rest of the article as an optional appendix.

Maybe is a data container that models the absence or presence of a value. Contrary to null, Maybe has a type, so offers a sane and reasonable way to model that situation.

C# catamorphism #

This article uses Church-encoded Maybe. Other, alternative implementations of Maybe are possible. The catamorphism for Maybe is the Match method:

TResult Match<TResult>(TResult nothing, Func<T, TResult> just);

Like the Peano catamorphism, the Maybe catamorphism is a pair of a value and a function. The nothing value corresponds to the absence of data, whereas the just function handles the presence of data.

Given, for example, a Maybe containing a number, you can use Match to get the value out of the Maybe:

> IMaybe<int> maybe = new Just<int>(42); > maybe.Match(0, x => x) 42 > IMaybe<int> maybe = new Nothing<int>(); > maybe.Match(0, x => x) 0

The functionality is, however, more useful than a simple get-value-or-default operation. Often, you don't have a good default value for the type potentially wrapped in a Maybe object. In the core of your application architecture, it may not be clear how to deal with, say, the absence of a Reservation object, whereas at the boundary of your system, it's evident how to convert both absence and presence of data into a unifying type, such as an HTTP response:

Maybe<Reservation> maybe = // ... return maybe .Select(r => Repository.Create(r)) .Match<IHttpActionResult>( nothing: Content( HttpStatusCode.InternalServerError, new HttpError("Couldn't accept.")), just: id => Ok(id));

This enables you to avoid special cases, such as null Reservation objects, or magic numbers like -1 to indicate the absence of id values. At the boundary of an HTTP-based application, you know that you must return an HTTP response. That's the unifying type, so you can return 200 OK with a reservation ID in the response body when data is present, and 500 Internal Server Error when data is absent.

Maybe F-Algebra #

As in the previous article, I'll use Fix and cata as explained in Bartosz Milewski's excellent article on F-Algebras.

While F-Algebras and fixed points are mostly used for recursive data structures, you can also define an F-Algebra for a non-recursive data structure. You already saw an example of that in the article about Boolean catamorphism. The difference between Boolean values and Maybe is that the just case of Maybe carries a value. You can model this as a Functor with both a carrier type and a type argument for the data that Maybe may contain:

data MaybeF a c = NothingF | JustF a deriving (Show, Eq, Read) instance Functor (MaybeF a) where fmap _ NothingF = NothingF fmap _ (JustF x) = JustF x

I chose to call the 'data type' a and the carrier type c (for carrier). As was also the case with BoolF, the Functor instance ignores the map function because the carrier type is missing from both the NothingF case and the JustF case. Like the Functor instance for BoolF, it'd seem that nothing happens, but at the type level, this is still a translation from MaybeF a c to MaybeF a c1. Not much of a function, perhaps, but definitely an endofunctor.

In the previous articles, it was possible to work directly with the fixed points of both functors; i.e. Fix BoolF and Fix NatF. Haskell isn't happy about attempts to define various instances for Fix (MaybeF a), so in order to make this easier, you can define a newtype wrapper:

newtype MaybeFix a = MaybeFix { unMaybeFix :: Fix (MaybeF a) } deriving (Show, Eq, Read)

In order to make it easier to work with MaybeFix you can add helper functions to create values:

nothingF :: MaybeFix a nothingF = MaybeFix $ Fix NothingF justF :: a -> MaybeFix a justF = MaybeFix . Fix . JustF

You can now create MaybeFix values to your heart's content:

Prelude Fix Maybe> justF 42

MaybeFix {unMaybeFix = Fix (JustF 42)}

Prelude Fix Maybe> nothingF

MaybeFix {unMaybeFix = Fix NothingF}

That's all you need to identify the catamorphism.

Haskell catamorphism #

At this point, you have two out of three elements of an F-Algebra. You have an endofunctor (MaybeF), and an object a, but you still need to find a morphism MaybeF a c -> c. Notice that the algebra you have to find is the function that reduces the functor to its carrier type c, not the 'data type' a. This takes some time to get used to, but that's how catamorphisms work. This doesn't mean, however, that you get to ignore a, as you'll see.

As in the previous article, start by writing a function that will become the catamorphism, based on cata:

maybeF = cata alg . unMaybeFix where alg NothingF = undefined alg (JustF x) = undefined

While this compiles, with its undefined implementations, it obviously doesn't do anything useful. I find, however, that it helps me think. How can you return a value of the type c from the NothingF case? You could pass an argument to the maybeF function:

maybeF n = cata alg . unMaybeFix where alg NothingF = n alg (JustF x) = undefined

The JustF case, contrary to NothingF, already contains a value, and it'd be incorrect to ignore it. On the other hand, x is a value of type a, and you need to return a value of type c. You'll need a function to perform the conversion, so pass such a function as an argument to maybeF as well:

maybeF :: c -> (a -> c) -> MaybeFix a -> c maybeF n f = cata alg . unMaybeFix where alg NothingF = n alg (JustF x) = f x

This works. Since cata has the type Functor f => (f a -> a) -> Fix f -> a, that means that alg has the type f a -> a. In the case of MaybeF, the compiler infers that the alg function has the type MaybeF a c -> c, which is just what you need!

You can now see what the carrier type c is for. It's the type that the algebra extracts, and thus the type that the catamorphism returns.

Notice that maybeF, like the above C# Match method, takes as arguments a pair of a value and a function (together with the Maybe value itself). Those are two representations of the same idea. Furthermore, this is nearly identical to the maybe function in Haskell's Data.Maybe module. I found it fitting, therefore, to name the function maybeF.

Basis #

You can implement most other useful functionality with maybeF. Here's the Functor instance:

instance Functor MaybeFix where fmap f = maybeF nothingF (justF . f)

Since fmap should be a structure-preserving map, you'll have to map the nothing case to the nothing case, and just to just. When calling maybeF, you must supply a value for the nothing case and a function to deal with the just case. The nothing case is easy to handle: just use nothingF.

In the just case, first apply the function f to map from a to b, and then use justF to wrap the b value in a new MaybeFix container to get MaybeFix b.

Applicative is a little harder, but not much:

instance Applicative MaybeFix where pure = justF f <*> x = maybeF nothingF (<$> x) f

The pure function is just justF (pun intended). The apply operator <*> is more complex.

Both f and x surrounding <*> are MaybeFix values: f is MaybeFix (a -> b), and x is MaybeFix a. While it's becoming increasingly clear that you can use a catamorphism like maybeF to implement most other functionality, to which MaybeFix value should you apply it? To f or x?

Both are possible, but the code looks (in my opinion) more readable if you apply it to f. Again, when f is nothing, return nothingF. When f is just, use the functor instance to map x (using the infix fmap alias <$>).

The Monad instance, on the other hand, is almost trivial:

instance Monad MaybeFix where x >>= f = maybeF nothingF f x

As usual, map nothing to nothing by supplying nothingF. f is already a function that returns a MaybeFix b value, so just use that.

The Foldable instance is likewise trivial (although, as you'll see below, you can make it even more trivial):

instance Foldable MaybeFix where foldMap = maybeF mempty

The foldMap function must return a Monoid instance, so for the nothing case, simply return the identity, mempty. Furthermore, foldMap takes a function a -> m, but since the foldMap implementation is point-free, you can't 'see' that function as an argument.

Finally, for the sake of completeness, here's the Traversable instance:

instance Traversable MaybeFix where sequenceA = maybeF (pure nothingF) (justF <$>)

In the nothing case, you can put nothingF into the desired Applicative with pure. In the just case you can take advantage of the desired Applicative being also a Functor by simply mapping the inner value(s) with justF.

Since the Applicative instance for MaybeFix equals pure to justF, you could alternatively write the Traversable instance like this:

instance Traversable MaybeFix where sequenceA = maybeF (pure nothingF) (pure <$>)

I like this alternative less, since I find it confusing. The two appearances of pure relate to two different types. The pure in pure nothingF has the type MaybeFix a -> f (MaybeFix a), while the pure in pure <$> has the type a -> MaybeFix a!

Both implementations work the same, though:

Prelude Fix Maybe> sequenceA (justF ("foo", 42))

("foo",MaybeFix {unMaybeFix = Fix (JustF 42)})

Here, I'm using the Applicative instance of (,) String.

Finally, you can implement conversions to and from the standard Maybe type, using ana as the dual of cata:

toMaybe :: MaybeFix a -> Maybe a toMaybe = maybeF Nothing return fromMaybe :: Maybe a -> MaybeFix a fromMaybe = MaybeFix . ana coalg where coalg Nothing = NothingF coalg (Just x) = JustF x

This demonstrates that MaybeFix is isomorphic to Maybe, which again establishes that maybeF and maybe are equivalent.

Alternatives #

As usual, the above maybeF isn't the only possible catamorphism. A trivial variation is to flip its arguments, but other variations exist.

It's a recurring observation that a catamorphism is just a generalisation of a fold. In the above code, the Foldable instance already looked as simple as anyone could desire, but another variation of a catamorphism for Maybe is this gratuitously embellished definition:

maybeF :: (a -> c -> c) -> c -> MaybeFix a -> c maybeF f n = cata alg . unMaybeFix where alg NothingF = n alg (JustF x) = f x n

This variation redundantly passes n as an argument to f, thereby changing the type of f to a -> c -> c. There's no particular motivation for doing this, apart from establishing that this catamorphism is exactly the same as the fold:

instance Foldable MaybeFix where foldr = maybeF

You can still implement the other instances as well, but the rest of the code suffers in clarity. Here's a few examples:

instance Functor MaybeFix where fmap f = maybeF (const . justF . f) nothingF instance Applicative MaybeFix where pure = justF f <*> x = maybeF (const . (<$> x)) nothingF f instance Monad MaybeFix where x >>= f = maybeF (const . f) nothingF x

I find that the need to compose with const does nothing to improve the readability of the code, so this variation is mostly, I think, of academic interest. It does show, though, that the catamorphism of Maybe is isomorphic to its fold, as the diagram in the overview article indicated:

You can demonstrate that this variation, too, is isomorphic to Maybe with a set of conversion:

toMaybe :: MaybeFix a -> Maybe a toMaybe = maybeF (const . return) Nothing fromMaybe :: Maybe a -> MaybeFix a fromMaybe = MaybeFix . ana coalg where coalg Nothing = NothingF coalg (Just x) = JustF x

Only toMaybe has changed, compared to above; the fromMaybe function remains the same. The only change to toMaybe is that the arguments have been flipped, and return is now composed with const.

Since (according to Conceptual Mathematics) isomorphisms are transitive this means that the two variations of maybeF are isomorphic. The latter, more complex, variation of maybeF is identical foldr, so we can consider the simpler, more frequently encountered variation a simplification of fold.

Summary #

The catamorphism for Maybe is the same as its Church encoding: a pair made from a default value and a function. In Haskell's base library, this is simply called maybe. In the above C# code, it's called Match.

This function is total, and you can implement any other functionality you need with it. I therefore consider it the canonical representation of Maybe, which is also why it annoys me that most Maybe implementations come equipped with partial functions like fromJust, or F#'s Option.get. Those functions shouldn't be part of a sane and reasonable Maybe API. You shouldn't need them.

In this series of articles about catamorphisms, you've now seen the first example of catamorphism and fold coinciding. In the next article, you'll see another such example - probably the most well-known catamorphism example of them all.

Next: List catamorphism.

Peano catamorphism

The catamorphism for Peano numbers involves a base value and a successor function.

This article is part of an article series about catamorphisms. A catamorphism is a universal abstraction that describes how to digest a data structure into a potentially more compact value.

This article presents the catamorphism for natural numbers, as well as how to identify it. The beginning of the article presents the catamorphism in C#, with examples. The rest of the article describes how I deduced the catamorphism. This part of the article presents my work in Haskell. Readers not comfortable with Haskell can just read the first part, and consider the rest of the article as an optional appendix.

C# catamorphism #

In this article, I model natural numbers using Peano's model, and I'll reuse the Church-encoded implementation you've seen before. The catamorphism for INaturalNumber is:

public static T Cata<T>(this INaturalNumber n, T zero, Func<T, T> succ) { return n.Match(zero, p => p.Cata(succ(zero), succ)); }

Notice that this is an extension method on INaturalNumber, taking two other arguments: a zero argument which will be returned when the number is zero, and a successor function to return the 'next' value based on a previous value.

The zero argument is the easiest to understand. It's simply passed to Match so that this is the value that Cata returns when n is zero.

The other argument to Match must be a Func<INaturalNumber, T>; that is, a function that takes an INaturalNumber as input and returns a value of the type T. You can supply such a function by using a lambda expression. This expression receives a predecessor p as input, and has to return a value of the type T. The only function available in this context, however, is succ, which has the type Func<T, T>. How can you make that work?

As is often the case when programming with generics, it pays to follow the types. A Func<T, T> requires an input of the type T. Do you have any T objects around?

The only available T object is zero, so you could call succ(zero) to produce another T value. While you could return that immediately, that'd ignore the predecessor p, so that's not going to work. Another option, which is the one that works, is to recursively call Cata with succ(zero) as the zero value, and succ as the second argument.

What this accomplishes is that Cata keeps recursively calling itself until n is zero. The zero object, however, will be the result of repeated applications of succ(zero). In other words, succ will be called as many times as the natural number. If n is 7, then succ will be called seven times, the first time with the original zero value, the next time with the result of succ(zero), the third time with the result of succ(succ(zero)), and so on. If the number is 42, succ will be called 42 times.

Arithmetic #

You can implement all the functionality you saw in the article on Church-encoded natural numbers. You can start gently by converting a Peano number into a normal C# int:

public static int Count(this INaturalNumber n) { return n.Cata(0, x => 1 + x); }

You can play with the functionality in C# Interactive to get a feel for how it works:

> NaturalNumber.Eight.Count() 8 > NaturalNumber.Five.Count() 5

The Count extension method uses Cata to count the level of recursion. The zero value is, not surprisingly, 0, and the successor function simply adds one to the previous number. Since the successor function runs as many times as encoded by the Peano number, and since the initial value is 0, you get the integer value of the number when Cata exits.

A useful building block you can write using Cata is a function to increment a natural number by one:

public static INaturalNumber Increment(this INaturalNumber n) { return n.Cata(One, p => new Successor(p)); }

This, again, works as you'd expect:

> NaturalNumber.Zero.Increment().Count() 1 > NaturalNumber.Eight.Increment().Count() 9

With the Increment method and Cata, you can easily implement addition:

public static INaturalNumber Add(this INaturalNumber x, INaturalNumber y) { return x.Cata(y, p => p.Increment()); }

The trick here is to use y as the zero case for x. In other words, if x is zero, then Add should return y. If x isn't zero, then Increment it as many times as the number encodes, but starting at y. In other words, start with y and Increment x times.

The catamorphism makes it much easier to implement arithmetic operation. Just consider multiplication, which wasn't the simplest implementation in the previous article. Now, it's as simple as this:

public static INaturalNumber Multiply(this INaturalNumber x, INaturalNumber y) { return x.Cata(Zero, p => p.Add(y)); }

Start at 0 and simply Add(y) x times.

> NaturalNumber.Nine.Multiply(NaturalNumber.Four).Count() 36

Finally, you can also implement some common predicates:

public static IChurchBoolean IsZero(this INaturalNumber n) { return n.Cata<IChurchBoolean>(new ChurchTrue(), _ => new ChurchFalse()); } public static IChurchBoolean IsEven(this INaturalNumber n) { return n.Cata<IChurchBoolean>(new ChurchTrue(), b => new ChurchNot(b)); } public static IChurchBoolean IsOdd(this INaturalNumber n) { return new ChurchNot(n.IsEven()); }

Particularly IsEven is elegant: It considers zero even, so simply uses a new ChurchTrue() object for that case. In all other cases, it alternates between false and true by negating the predecessor.

> NaturalNumber.Three.IsEven().ToBool()

false

It seems convincing that we can use Cata to implement all the other functionality we need. That seems to be a characteristic of a catamorphism. Still, how do we know that Cata is, in fact, the catamorphism for natural numbers?

Peano F-Algebra #

As in the previous article, I'll use Fix and cata as explained in Bartosz Milewski's excellent article on F-Algebras. The NatF type comes from his article as well:

data NatF a = ZeroF | SuccF a deriving (Show, Eq, Read) instance Functor NatF where fmap _ ZeroF = ZeroF fmap f (SuccF x) = SuccF $ f x

You can use the fixed point of this functor to define numbers with a shared type. Here's just the first ten:

zeroF, oneF, twoF, threeF, fourF, fiveF, sixF, sevenF, eightF, nineF :: Fix NatF zeroF = Fix ZeroF oneF = Fix $ SuccF zeroF twoF = Fix $ SuccF oneF threeF = Fix $ SuccF twoF fourF = Fix $ SuccF threeF fiveF = Fix $ SuccF fourF sixF = Fix $ SuccF fiveF sevenF = Fix $ SuccF sixF eightF = Fix $ SuccF sevenF nineF = Fix $ SuccF eightF

That's all you need to identify the catamorphism.

Haskell catamorphism #

At this point, you have two out of three elements of an F-Algebra. You have an endofunctor (NatF), and an object a, but you still need to find a morphism NatF a -> a.

As in the previous article, start by writing a function that will become the catamorphism, based on cata:

natF = cata alg where alg ZeroF = undefined alg (SuccF predecessor) = undefined

While this compiles, with its undefined implementations, it obviously doesn't do anything useful. I find, however, that it helps me think. How can you return a value of the type a from the ZeroF case? You could pass an argument to the natF function:

natF z = cata alg where alg ZeroF = z alg (SuccF predecessor) = undefined

In the SuccF case, predecessor is already of the polymorphic type a, so instead of returning a constant value, you can supply a function as an argument to natF and use it in that case:

natF :: a -> (a -> a) -> Fix NatF -> a natF z next = cata alg where alg ZeroF = z alg (SuccF predecessor) = next predecessor

This works. Since cata has the type Functor f => (f a -> a) -> Fix f -> a, that means that alg has the type f a -> a. In the case of NatF, the compiler infers that the alg function has the type NatF a -> a, which is just what you need!

For good measure, I should point out that, as usual, the above natF function isn't the only possible catamorphism. Trivially, you can flip the order of the arguments, and this would also be a catamorphism. These two alternatives are isomorphic.

The natF function identifies the Peano number catamorphism, which is equivalent to the C# representation in the beginning of the article. I called the function natF, because there's a tendency in Haskell to name the 'case analysis' or catamorphism after the type, just with a lower-case initial letter.

Basis #

A catamorphism can be used to implement most (if not all) other useful functionality, like all of the above C# functionality. In fact, I wrote the Haskell code first, and then translated my implementations into the above C# extension methods. This means that the following functions apply the same reasoning:

evenF :: Fix NatF -> Fix BoolF evenF = natF trueF notF oddF :: Fix NatF -> Fix BoolF oddF = notF . evenF incF :: Fix NatF -> Fix NatF incF = natF oneF $ Fix . SuccF addF :: Fix NatF -> Fix NatF -> Fix NatF addF x y = natF y incF x multiplyF :: Fix NatF -> Fix NatF -> Fix NatF multiplyF x y = natF zeroF (addF y) x

Here are some GHCi usage examples:

Prelude Boolean Nat> evenF eightF Fix TrueF Prelude Boolean Nat> toNum $ multiplyF sevenF sixF 42

The toNum function corresponds to the above Count C# method. It is, again, based on cata. You can use ana to convert the other way:

toNum :: Num a => Fix NatF -> a toNum = natF 0 (+ 1) fromNum :: (Eq a, Num a) => a -> Fix NatF fromNum = ana coalg where coalg 0 = ZeroF coalg x = SuccF $ x - 1

This demonstrates that Fix NatF is isomorphic to Num instances, such as Integer.

Summary #

The catamorphism for Peano numbers is a pair consisting of a zero value and a successor function. The most common description of catamorphisms that I've found emphasise how a catamorphism is like a fold; an operation you can use to reduce a data structure like a list or a tree to a single value. This is what happens here, but even so, the Fix NatF type isn't a Foldable instance. The reason is that while NatF is a polymorphic type, its fixed point Fix NatF isn't. Haskell's Foldable type class requires foldable containers to be polymorphic (what C# programmers would call 'generic').

When I first ran into the concept of a catamorphism, it was invariably described as a 'generalisation of fold'. The examples shown were always how the catamorphism for linked list is the same as its fold. I found such explanations unhelpful, because I couldn't understand how those two concepts differ.

The purpose with this article series is to show just how much more general the abstraction of a catamorphism is. In this article you saw how an infinitely recursive data structure like Peano numbers have a catamorphism, even though it isn't a parametrically polymorphic type. In the next article, though, you'll see the first example of a polymorphic type where the catamorphism coincides with the fold.

Next: Maybe catamorphism.

Boolean catamorphism

The catamorphism for Boolean values is just the common ternary operator.

This article is part of an article series about catamorphisms. A catamorphism is a universal abstraction that describes how to digest a data structure into a potentially more compact value.

This article presents the catamorphism for Boolean values, as well as how you identify it. The beginning of this article presents the catamorphism in C#, with a simple example. The rest of the article describes how I deduced the catamorphism. That part of the article presents my work in Haskell. Readers not comfortable with Haskell can just read the first part, and consider the rest of the article as an optional appendix.

C# catamorphism #

The catamorphism for Boolean values is the familiar ternary conditional operator:

> DateTime.Now.Day % 2 == 0 ? "Even date" : "Odd date" "Odd date"

Given a Boolean expression, you basically provide two values: one to use in case the Boolean expression is true, and one to use in case it's false.

For Church-encoded Boolean values, the catamorphism looks like this:

T Match<T>(T trueCase, T falseCase);

This is an instance method where you must, again, supply two alternatives. When the instance represents true, you'll get the left-most value trueCase; otherwise, when the instance represents false, you'll get the right-most value falseCase.

The catamorphism turns out to be the same as the Church encoding. This seems to be a recurring pattern.

Alternatives #

To be accurate, there's more than one catamorphism for Boolean values. It's only by convention that the value corresponding to true goes on the left, and the false value goes to the right. You could flip the arguments, and it would still be a catamorphism. This is, in fact, what Haskell's Data.Bool module does:

Prelude Data.Bool> bool "Odd date" "Even date" $ even date "Odd date"

The module documentation calls this the "Case analysis for the Bool type", instead of a catamorphism, but the two representations are isomorphic:

"This is equivalent to if p then y else x; that is, one can think of it as an if-then-else construct with its arguments reordered."

This is another recurring result. There's typically more than one catamorphism, but the alternatives are isomorphic. In this article series, I'll mostly present the alternative that strikes me as the one you'll encounter most frequently.

Fix #

In this and future articles, I'll derive the catamorphism from an F-Algebra. For an introduction to F-Algebras and fixed points, I'll refer you to Bartosz Milewski's excellent article on the topic. In it, he presents a generic data type for a fixed point, as well as polymorphic functions for catamorphisms and anamorphisms. While they're available in his article, I'll repeat them here for good measure:

newtype Fix f = Fix { unFix :: f (Fix f) } cata :: Functor f => (f a -> a) -> Fix f -> a cata alg = alg . fmap (cata alg) . unFix ana :: Functor f => (a -> f a) -> a -> Fix f ana coalg = Fix . fmap (ana coalg) . coalg

This should be recognisable from Bartosz Milewski's article. With one small exception, this is just a copy of the code shown there.

Boolean F-Algebra #

While F-Algebras and fixed points are mostly used for recursive data structures, you can also define an F-Algebra for a non-recursive data structure. As data types go, they don't get much simpler than Boolean values, which are just two mutually exclusive cases. In order to make a Functor out of the definition, though, you can equip it with a carrier type:

data BoolF a = TrueF | FalseF deriving (Show, Eq, Read) instance Functor BoolF where fmap _ TrueF = TrueF fmap _ FalseF = FalseF

The Functor instance simply ignores the carrier type and just returns TrueF and FalseF, respectively. It'd seem that nothing happens, but at the type level, this is still a translation from BoolF a to BoolF b. Not much of a function, perhaps, but definitely an endofunctor.

Another note that may be in order here, as well as for all future articles in this series, is that you'll notice that most types and custom functions come with the F suffix. This is simply a suffix I've added to avoid conflicts with built-in types, values, and functions, such as Bool, True, and, and so on. The F is for F-Algebra.

You can lift these values into Fix in order to make it fit with the cata function:

trueF, falseF :: Fix BoolF trueF = Fix TrueF falseF = Fix FalseF

That's all you need to identify the catamorphism.

Haskell catamorphism #

At this point, you have two out of three elements of an F-Algebra. You have an endofunctor (BoolF), and an object a, but you still need to find a morphism BoolF a -> a. At first glance, this seems impossible, because neither TrueF nor FalseF actually contain a value of the type a. How, then, can you conjure an a value out of thin air?

The cata function has the answer.

What you can do is to start writing the function that will become the catamorphism, basing it on cata:

boolF = cata alg where alg TrueF = undefined alg FalseF = undefined

While this compiles, with its undefined implementations, it obviously doesn't do anything useful. I find, however, that it helps me think. How can you return a value of the type a from the TrueF case? You could pass an argument to the boolF function:

boolF x = cata alg where alg TrueF = x alg FalseF = undefined

That seems promising, so do that for the FalseF case as well:

boolF :: a -> a -> Fix BoolF -> a boolF x y = cata alg where alg TrueF = x alg FalseF = y

This works. Since cata has the type Functor f => (f a -> a) -> Fix f -> a, that means that alg has the type f a -> a. In the case of BoolF, the compiler infers that the alg function has the type BoolF a -> a, which is just what you need!

The boolF function identifies the Boolean catamorphism, which is equivalent to representations in the beginning of the article. I called the function boolF, because there's a tendency in Haskell to name the 'case analysis' or catamorphism after the type, just with a lower-case initial letter.

You can use the boolF function just like the above ternary operator:

Prelude Boolean Nat> boolF "Even date" "Odd date" $ evenF dateF "Odd date"

Here, I've also used evenF from the Nat module shown in the next article in the series.

From the above definition of boolF, it should also be clear that you can arrive at the alternative catamorphism defined by Data.Bool.bool by simply flipping x and y.

Basis #

A catamorphism can be used to implement most (if not all) other useful functionality. For Boolean values, that would be the standard Boolean operations and, or, and not:

andF :: Fix BoolF -> Fix BoolF -> Fix BoolF andF x y = boolF y falseF x orF :: Fix BoolF -> Fix BoolF -> Fix BoolF orF x y = boolF trueF y x notF :: Fix BoolF -> Fix BoolF notF = boolF falseF trueF

They work as you'd expect them to work:

Prelude Boolean> andF trueF falseF Fix FalseF Prelude Boolean> orF trueF falseF Fix TrueF Prelude Boolean> orF (notF trueF) falseF Fix FalseF

You can also implement conversion to and from the built-in Bool type:

toBool :: Fix BoolF -> Bool toBool = boolF True False fromBool :: Bool -> Fix BoolF fromBool = ana coalg where coalg True = TrueF coalg False = FalseF

This demonstrates that Fix BoolF is isomorphic to Bool.

Summary #

The catamorphism for Boolean values is a function, method, or operator akin to the familiar ternary conditional operator. The most common descriptions of catamorphisms that I've found emphasise how a catamorphism is like a fold; an operation you can use to reduce a data structure like a list or a tree to a single value. In that light, it may be surprising that something as simple as Boolean values have an associated catamorphism.

Since Fix BoolF is isomorphic to Bool, you may wonder what the point is. Why define this data type, and implement functions like andF, orF, and notF?

The code presented here is nothing but an analysis tool. It's a way to identify the catamorphism for Boolean values.

Next: Peano catamorphism.

Catamorphisms

A catamorphism is a general abstraction that enables you to handle multiple values, for example in order to reduce them to a single value.

This article series is part of an even larger series of articles about the relationship between design patterns and category theory. In another article series in this big series of articles, you learned about functors, applicatives, and other types of data containers.

You may have heard about map-reduce architectures. Much software can be designed around two general types of operations: those that map data, and those that reduce data. A functor is a container of data that supports structure-preserving maps. Thus, you can think of functors as the general abstraction for map operations (also sometimes called projections). Does a similar universal abstraction exist for operations that reduce data?

Yes, that abstraction is called a catamorphism.

Aggregation #

Catamorphism is an intimidating word, so let's start with an example. You often have a collection of values that you'd like to reduce to a single value. Such a collection can contain arbitrarily complex objects, but I'll keep it simple and start with a collection of numbers:

new[] { 42, 1337, 2112, 90125, 5040, 7, 1984 };

This particular list of numbers is an array, but that's not important. What comes next works for any IEnumerable<T>, including arrays. I only chose an array because the C# syntax for array creation is more compact than for other collection types.

How do you reduce those seven numbers to a single number? That depends on what you want that number to tell you. One option is to add the numbers together. There's a specific, built-in function for that:

> new[] { 42, 1337, 2112, 90125, 5040, 7, 1984 }.Sum();

100647

The Sum extension method is a one of many built-in functions that enable you to reduce a list of numbers to a single number: Average, Max, Count, and so on.

What do you do, though, if you need to reduce many values to one, and there's no existing function for that? What if, for example, you need to add all the numbers using modulo 360 addition?

In that case, you use Aggregate:

> new[] { 42, 1337, 2112, 90125, 5040, 7, 1984 }.Aggregate((x, y) => (x + y) % 360)

207

The way to interpret this result is that the initial array represents a sequence of rotations (measured in degrees), and the result is the final angle after all the rotations have completed.

In other (functional) languages, such a 'reduce' operation is called a fold. The metaphor, I suppose, is that you fold multiple values together, two by two.

A fold is a catamorphism, but a catamorphism is a more general abstraction. For some data structures, the catamorphism is more powerful than the fold, but for collections, there's no difference.

There's one edge case we need to be aware of, though. What if the collection is empty?

Aggregation of empty containers #

What happens if you attempt to aggregate an empty collection?

> new int[0].Aggregate((x, y) => (x + y) % 360) Sequence contains no elements + System.Linq.Enumerable.Aggregate<TSource>(IEnumerable<TSource>, Func<TSource, TSource, TSource>)

The Aggregate method throws an exception because it doesn't know how to deal with empty collections. The lambda expression you supply tells the Aggregate method how to combine two values into one. This is, for instance, how semigroups accumulate.

The lambda expression handles all cases where you have two or more values. If you have only a single value, then that's no problem either:

> new[] { 1337 }.Aggregate((x, y) => (x + y) % 360)

1337

In that case, the lambda expression isn't involved at all, because the single value is simply returned without modification. In this example, this could even be interpreted as being incorrect, since you'd expect the result to be 257 (1337 % 360).

It's safer to use the Aggregate overload that takes a seed value:

> new int[0].Aggregate(0, (x, y) => (x + y) % 360) 0

Not only does that gracefully handle empty collections, it also gives you a 'better' result for a single value:

> new[] { 1337 }.Aggregate(0, (x, y) => (x + y) % 360)

257

This works better because the method always starts with the seed value, which means that even if there's only a single value (1337), the lambda expression still runs ((0 + 1337) % 360).

This overload of Aggregate has a different type, though:

public static TAccumulate Aggregate<TSource, TAccumulate>( this IEnumerable<TSource> source, TAccumulate seed, Func<TAccumulate, TSource, TAccumulate> func);

Notice that the func doesn't require the accumulator to have the same type as elements from the source collection. This enables you to translate on the fly, so to speak. You can still use binary operations like the above modulo 360 addition, because that just implies that both TSource and TAccumulate are int.

With this overload, you could, for example, use the Angle class to perform the work:

> new[] { 42, 1337, 2112, 90125, 5040, 7, 1984 } . .Aggregate(Angle.Identity, (a, i) => a.Add(Angle.FromDegrees(i))) [{ Angle = 207° }]

Now the seed argument is Angle.Identity, which implies that TAccumulate is Angle. The source is still a collection of numbers, so TSource is int. Hence, I called the angle a and the integer i in the lambda expression. The output is an Angle object that represents 207°.

That Aggregate overload is the catamorphism for collections. It reduces a collection to an object.

Catamorphisms and folds #

Is catamorphism just an intimidating word for aggregate, accumulate, fold, or reduce?

It took me a long time to be able to tell the difference, because in many cases, it seems that there's no difference. The purpose of this article series is to make the distinction clearer. In short, a catamorphism is a more general concept.

For some data structures, such as Boolean values, or Peano numbers, the catamorphism is all there is; no fold exists. For other data structures, such as Maybe or collections, the catamorphism and the fold coincide. Still other data structures, such as Either and trees, support folding, but the fold is based on the catamorphism. For those types, there are operations you can do with the catamorphism that are impossible to implement with the fold function. One example is that a tree's catamorphism enables you to count its leaves; you can't do that with its fold function.

You'll see plenty of examples in this article series:

- Boolean catamorphism

- Peano catamorphism

- Maybe catamorphism

- List catamorphism

- NonEmpty catamorphism

- Either catamorphism

- Tree catamorphism

- Rose tree catamorphism

- Full binary tree catamorphism

- Payment types catamorphism

Each of these articles will contain a fair amount of Haskell code, but even if you're an object-oriented programmer who doesn't read Haskell, you should still scan them, as I'll start each with some C# examples. The Haskell code, by the way, is available on GitHub.

Greek #

When encountering a word like catamorphism, your reaction might be:

"Catamorphism?! What does that even mean? It's all Greek to me."Indeed, it's Greek, as is so much of mathematical terminology. The cata prefix means 'down'; lots of words start with cata, like catastrophe, catalogue, catatonia, catacomb, etc.

The morph suffix generally means 'shape'. While the cata prefix appears in common words like catastrophe, the morph suffix mostly appears in more academic contexts. Programmers will probably have encountered polymorphism and skeuomorphism, not to mention isomorphism. While morphism is heavily used in mathematics, other sciences use the suffix too, like dimorphism in biology.

In category theory, a morphism is basically just an arrow that points from one object to another. Think of it as a function.

If a morphism is just a function, why don't we just call it that, then? Is it really necessary with this intimidating terminology? Yes and no.

If someone had originally figured all of this out in the context of mainstream programming, he or she would probably have used friendlier names, like condense, reduce, fold, and so on. This would have been more encouraging, although I'm not sure it would have been better.

In software architecture we use many overloaded terms. For example, what's a service, or a client? What does tier mean? Is it the same as a layer, or is it something different? What's the difference between a library and a framework?

At least a word like catamorphism is concise. It's not in common use, so isn't overloaded and vague.

Another, more pragmatic, concern is that whether you like it or not, the terminology is already established. Mathematicians decided to name the concept catamorphism. While the name may seem intimidating, I prefer to teach concepts like these using established terminology. This means that if my articles are unclear, you can do further research with other resources. That's the benefit of established terminology, whether you like the specific words or not.

Summary #

You can compose entire applications based on the abstractions of map and reduce. You can see one example of such a system in my A Functional Architecture with F# Pluralsight course.

The terms map and reduce may, however, not be helpful, because it may not be clear exactly what types of data you can map, and what types you can reduce. One of the most important goals of this overall article series about universal abstractions is to help you identify when such software architectures apply. This is more often that you think.

What sort of data can you map? You can map functors. While hardly finite, there's a catalogue of well-known functors, of which I've covered some, but not all. That catalogue contains data containers like Maybe, Tree, lazy computations, tasks, and perhaps a score more. The catalogue of (actually useful) functors has, in my experience, a manageable size.

Likewise you could ask: What sort of data can you reduce? How do you implement that reduction? Again, there's a compact set of well-known catamorphisms. How do you reduce a collection? You use its catamorphism (which is equal to a fold). How do you reduce a tree? You use its catamorphism. How do you reduce an Either object? You use its catamorphism.

When we learn new programming languages, new libraries, new frameworks, we gladly invest time in learning hundreds, if not thousands, of keywords, APIs, extensibility points, and so on. May I offer, for your consideration, that your mental resources are better spent learning only a handful of universal abstractions?

Next: Boolean catamorphism.

Applicative monoids

An applicative functor containing monoidal values itself forms a monoid.

This article is an instalment in an article series about applicative functors. An applicative functor is a data container that supports combinations. If an applicative functor contains values of a type that gives rise to a monoid, then the functor itself forms a monoid.

In a previous article you learned that lazy computations of monoids remain monoids. Furthermore, a lazy computation is an applicative functor, and it turns out that the result generalises. The result regarding lazy computation is just a special case.

Monap #

Since version 4.11 of Haskell's base library, Monoid is a subset of Semigroup, so in order to create a Monoid instance, you must first define a Semigroup instance.

In order to escape the need for flexible contexts, you'll have to define a wrapper newtype that'll be the instance. What should you call it? It's going to be an applicative functor of monoids, so perhaps something like ApplicativeMonoid? Nah, that's too long. AppMon, then? Sure, but how about flipping the terms: MonApp? That's better. Let's drop the last p and dispense with the Pascal case: Monap.

Monap almost looks like Monad, only with the last letter rotated half a revolution. This should allow for maximum confusion.

To be clear, I normally don't advocate for droll word play when writing production code, but I occasionally do it in articles and presentations. The Monap in this article exists only to illustrate a point. It's not intended to be used. Furthermore, this article doesn't discuss monads at all, so the risk of confusion should, hopefully, be minimised. I may, however, regret this decision...

Applicative semigroup #

First, introduce the wrapper newtype:

newtype Monap f a = Monap { runMonap :: f a } deriving (Show, Eq)

This only states that there's a type called Monap that wraps some higher-kinded type f a; that is, a container f of values of the type a. The intent is that f is an applicative functor, hence the use of the letter f, but the type itself doesn't constrain f to any type class.

The Semigroup instance does, though:

instance (Applicative f, Semigroup a) => Semigroup (Monap f a) where (Monap x) <> (Monap y) = Monap $ liftA2 (<>) x y

This states that when f is a Applicative instance, and a is a Semigroup instance, then Monap f a is also a Semigroup instance.

Here's an example of combining two applicative semigroups:

λ> Monap (Just (Max 42)) <> Monap (Just (Max 1337))

Monap {runMonap = Just (Max {getMax = 1337})}

This example uses the Max semigroup container, and Maybe as the applicative functor. For Max, the <> operator returns the value that contains the highest value, which in this case is 1337.

It even works when the applicative functor in question is IO:

λ> runMonap $ Monap (Sum <$> randomIO @Word8) <> Monap (Sum <$> randomIO @Word8)

Sum {getSum = 165}

This example uses randomIO to generate two random values. It uses the TypeApplications GHC extension to make randomIO generate Word8 values. Each random number is projected into the Sum container, which means that <> will add the numbers together. In the above example, the result is 165, but if you evaluate the expression a second time, you'll most likely get another result:

λ> runMonap $ Monap (Sum <$> randomIO @Word8) <> Monap (Sum <$> randomIO @Word8)

Sum {getSum = 246}

You can also use linked list ([]) as the applicative functor. In this case, the result may be surprising (depending on what you expect):

λ> Monap [Product 2, Product 3] <> Monap [Product 4, Product 5, Product 6]

Monap {runMonap = [Product {getProduct = 8},Product {getProduct = 10},Product {getProduct = 12},

Product {getProduct = 12},Product {getProduct = 15},Product {getProduct = 18}]}

Notice that we get all the combinations of products: 2 multiplied with each element in the second list, followed by 3 multiplied by each of the elements in the second list. This shouldn't be that startling, though, since you've already, previously in this article series, seen several examples of how an applicative functor implies combinations.

Applicative monoid #

With the Semigroup instance in place, you can now add the Monoid instance:

instance (Applicative f, Monoid a) => Monoid (Monap f a) where mempty = Monap $ pure $ mempty

This is straightforward: you take the identity (mempty) of the monoid a, promote it to the applicative functor f with pure, and finally put that value into the Monap wrapper.

This works fine as well:

λ> mempty :: Monap Maybe (Sum Integer)

Monap {runMonap = Just (Sum {getSum = 0})}

λ> mempty :: Monap [] (Product Word8)

Monap {runMonap = [Product {getProduct = 1}]}

The identity laws also seem to hold:

λ> Monap (Right mempty) <> Monap (Right (Sum 2112))

Monap {runMonap = Right (Sum {getSum = 2112})}

λ> Monap ("foo", All False) <> Monap mempty

Monap {runMonap = ("foo",All {getAll = False})}

The last, right-identity example is interesting, because the applicative functor in question is a tuple. Tuples are Applicative instances when the first, or left, element is a Monoid instance. In other words, f is, in this case, (,) String. The Monoid instance that Monap sees as a, on the other hand, is All.

Since tuples of monoids are themselves monoids, however, I can get away with writing Monap mempty on the right-hand side, instead of the more elaborate template the other examples use:

λ> Monap ("foo", All False) <> Monap ("", mempty)

Monap {runMonap = ("foo",All {getAll = False})}

or perhaps even:

λ> Monap ("foo", All False) <> Monap (mempty, mempty)

Monap {runMonap = ("foo",All {getAll = False})}

Ultimately, all three alternatives mean the same.

Associativity #

As usual, I'm not going to do the work of formally proving that the monoid laws hold for the Monap instances, but I'd like to share some QuickCheck properties that indicate that they do, starting with a property that verifies associativity:

assocLaw :: (Eq a, Show a, Semigroup a) => a -> a -> a -> Property assocLaw x y z = (x <> y) <> z === x <> (y <> z)

This property is entirely generic. It'll verify associativity for any Semigroup a, not only for Monap. You can, however, run it for various Monap types, as well. You'll see how this is done a little later.

Identity #

Likewise, you can write two properties that check left and right identity, respectively.

leftIdLaw :: (Eq a, Show a, Monoid a) => a -> Property leftIdLaw x = x === mempty <> x rightIdLaw :: (Eq a, Show a, Monoid a) => a -> Property rightIdLaw x = x === x <> mempty

Again, this is entirely generic. These properties can be used to test the identity laws for any monoid, including Monap.

Properties #

You can run each of these properties multiple time, for various different functors and monoids. As Applicative instances, I've used Maybe, [], (,) Any, and Identity. As Monoid instances, I've used String, Sum Integer, Max Int16, and [Float]. Notice that a list ([]) is both an applicative functor as well as a monoid. In this test set, I've used it in both roles.

tests = [ testGroup "Properties" [ testProperty "Associativity law, Maybe String" (assocLaw @(Monap Maybe String)), testProperty "Left identity law, Maybe String" (leftIdLaw @(Monap Maybe String)), testProperty "Right identity law, Maybe String" (rightIdLaw @(Monap Maybe String)), testProperty "Associativity law, [Sum Integer]" (assocLaw @(Monap [] (Sum Integer))), testProperty "Left identity law, [Sum Integer]" (leftIdLaw @(Monap [] (Sum Integer))), testProperty "Right identity law, [Sum Integer]" (rightIdLaw @(Monap [] (Sum Integer))), testProperty "Associativity law, (Any, Max Int8)" (assocLaw @(Monap ((,) Any) (Max Int8))), testProperty "Left identity law, (Any, Max Int8)" (leftIdLaw @(Monap ((,) Any) (Max Int8))), testProperty "Right identity law, (Any, Max Int8)" (rightIdLaw @(Monap ((,) Any) (Max Int8))), testProperty "Associativity law, Identity [Float]" (assocLaw @(Monap Identity [Float])), testProperty "Left identity law, Identity [Float]" (leftIdLaw @(Monap Identity [Float])), testProperty "Right identity law, Identity [Float]" (rightIdLaw @(Monap Identity [Float])) ] ]

All of these properties pass.

Summary #

It seems that any applicative functor that contains monoidal values itself forms a monoid. The Monap type presented in this article only exists to demonstrate this conjecture; it's not intended to be used.

If it holds, I think it's an interesting result, because it further enables you to reason about the properties of complex systems, based on the properties of simpler systems.

Next: Bifunctors.

Comments

It seems that any applicative functor that contains monoidal values itself forms a monoid.

Is it necessary for the functor to be applicative? Do you know of a functor that contains monoidal values for which itself does not form a monoid?

Tyson, thank you for writing. Yes, it's necessary for the functor to be applicative, because you need the applicative combination operator <*> in order to implement the combination. In C#, you'd need an Apply method as shown here.

Technically, the monoidal <> operator for Monap is, as you can see, implemented with a call to liftA2. In Haskell, you can implement an instance of Applicative by implementing either liftA2 or <*>, as well as pure. You usually see Applicative described by <*>, which is what I've done in my article series on applicative functors. If you do that, you can define liftA2 by a combination of <*> and fmap (the Select method that defines functors).

If you want to put this in C# terms, you need both Select and Apply in order to be able to lift a monoid into a functor.

Is there a functor that contains monoidal values that itself doesn't form a monoid?

Yes, indeed. In order to answer that question, we 'just' need to identify a functor that's not an applicative functor. Tuples are good examples.

A tuple forms a functor, but in general nothing more than that. Consider a tuple where the first element is a Guid. It's a functor, but can you implement the following function?

public static Tuple<Guid, TResult> Apply<TResult, T>( this Tuple<Guid, Func<T, TResult>> selector, Tuple<Guid, T> source) { throw new NotImplementedException("What would you write here?"); }

You can pull the T value out of source and project it to a TResult value with selector, but you'll need to put it back in a Tuple<Guid, TResult>. Which Guid value are you going to use for that tuple?

There's no clear answer to that question.

More specifically, consider Tuple<Guid, int>. This is a functor that contains monoidal values. Let's say that we want to use the addition monoid over integers. How would you implement the following method?

public static Tuple<Guid, int> Add(this Tuple<Guid, int> x, Tuple<Guid, int> y) { throw new NotImplementedException("What would you write here?"); }

Again, you run into the issue that while you can pull the integers out of the tuples and add them together, there's no clear way to figure out which Guid value to put into the tuple that contains the sum.

The issue particularly with tuples is that there's no general way to combine the leftmost values of the tuples. If there is - that is, if leftmost values form a monoid - then the tuple is also an applicative functor. For example, Tuple<string, int> is applicative and forms a monoid over addition: