ploeh blog danish software design

Robust DI With the ASP.NET Web API

Note 2014-04-03 19:46 UTC: This post describes how to address various Dependency Injection issues with a Community Technical Preview (CTP) of ASP.NET Web API 1. Unless you're still using that 2012 CTP, it's no longer relevant. Instead, refer to my article about Dependency Injection with the final version of Web API 1 (which is also relevant for Web API 2).

Like the WCF Web API, the new ASP.NET Web API supports Dependency Injection (DI), but the approach is different and the resulting code you'll have to write is likely to be more complex. This post describes how to enable robust DI with the new Web API. Since this is based on the beta release, I hope that it will become easier in the final release.

At first glance, enabling DI on an ASP.NET Web API looks seductively simple. As always, though, the devil is in the details. Nikos Baxevanis has already provided a more thorough description, but it's even more tricky than that.

Protocol #

To enable DI, all you have to do is to call the SetResolver method, right? It even has an overload that enables you to supply two code blocks instead of implementing an interface (although you can certainly also implement IDependencyResolver). Could it be any easier than that?

Yes, it most certainly could.

Imagine that you'd like to hook up your DI Container of choice. As a first attempt, you try something like this:

GlobalConfiguration.Configuration.ServiceResolver.SetResolver( t => this.container.Resolve(t), t => this.container.ResolveAll(t).Cast<object>());

This compiles. Does it work? Yes, but in a rather scary manner. Although it satisfies the interface, it doesn't satisfy the protocol ("an interface describes whether two components will fit together, while a protocol describes whether they will work together." (GOOS, p. 58)).

The protocol, in this case, is that if you (or rather the container) can't resolve the type, you should return null. What's even worse is that if your code throws an exception (any exception, apparently), DependencyResolver will suppress it. In case you didn't know, this is strongly frowned upon in the .NET Framework Design Guidelines.

Even so, the official introduction article instead chooses to play along with the protocol and explicitly handle any exceptions. Something along the lines of this ugly code:

GlobalConfiguration.Configuration.ServiceResolver.SetResolver( t => { try { return this.container.Resolve(t); } catch (ComponentNotFoundException) { return null; } }, t => { try { return this.container.ResolveAll(t).Cast<object>(); } catch (ComponentNotFoundException) { return new List<object>(); } } );

Notice how try/catch is used for control flow - another major no no in the .NET Framework Design Guidelines.

At least with a good DI Container, we can do something like this instead:

GlobalConfiguration.Configuration.ServiceResolver.SetResolver( t => this.container.Kernel.HasComponent(t) ? this.container.Resolve(t) : null, t => this.container.ResolveAll(t).Cast<object>());

Still, first impressions don't exactly inspire trust in the implementation...

API Design Issues #

Next, I would like to direct your attention to the DependencyResolver API. At its core, it looks like this:

public interface IDependencyResolver { object GetService(Type serviceType); IEnumerable<object> GetServices(Type serviceType); }

It can create objects, but what about decommissioning? What if, deep in a dependency graph, a Controller contains an IDisposable object? This is not a particularly exotic scenario - it might be an instance of an Entity Framework ObjectContext. While an ApiController itself implements IDisposable, it may not know that it contains an injected object graph with one or more IDisposable leaf nodes.

It's a fundamental rule of DI that you must Release what you Resolve. That's not possible with the DependencyResolver API. The result may be memory leaks.

Fortunately, it turns out that there's a fix for this (at least for Controllers). Unfortunately, this workaround leverages another design problem with DependencyResolver.

Mixed Responsibilities #

It turns out that when you wire a custom resolver up with the SetResolver method, the ASP.NET Web API will query your custom resolver (such as a DI Container) for not only your application classes, but also for its own infrastructure components. That surprised me a bit because of the mixed responsibility, but at least this is a useful hook.

One of the first types the framework will ask for is an instance of IHttpControllerFactory, which looks like this:

public interface IHttpControllerFactory { IHttpController CreateController(HttpControllerContext controllerContext, string controllerName); void ReleaseController(IHttpController controller); }

Fortunately, this interface has a Release hook, so at least it's possible to release Controller instances, which is most important because there will be a lot of them (one per HTTP request).

Discoverability Issues #

The IHttpControllerFactory looks a lot like the well-known ASP.NET MVC IControllerFactory interface, but there are subtle differences. In ASP.NET MVC, there's a DefaultControllerFactory with appropriate virtual methods one can overwrite (it follows the Template Method pattern).

There's also a DefaultControllerFactory in the Web API, but unfortunately no Template Methods to override. While I could write an algorithm that maps from the controllerName parameter to a type which can be passed to a DI Container, I'd rather prefer to be able to reuse the implementation which the DefaultControllerFactory contains.

In ASP.NET MVC, this is possible by overriding the GetControllerInstance method, but it turns out that the Web API (beta) does this slightly differently. It favors composition over inheritance (which is actually a good thing, so kudos for that), so after mapping controllerName to a Type instance, it invokes an instance of the IHttpControllerActivator interface (did I hear anyone say "FactoryFactory?"). Very loosely coupled (good), but not very discoverable (not so good). It would have been more discoverable if DefaultControllerFactory had used Constructor Injection to get its dependency, rather than relying on the Service Locator which DependencyResolver really is.

However, this is only an issue if you need to hook into the Controller creation process, e.g. in order to capture the HttpControllerContext for further use. In normal scenarios, despite what Nikos Baxevanis describes in his blog post, you don't have to override or implement IHttpControllerFactory.CreateController. The DependencyResolver infrastructure will automatically invoke your GetService implementation (or the corresponding code block) whenever a Controller instance is required.

Releasing Controllers #

The easiest way to make sure that all Controller instances are being properly released is to derive a class from DefaultControllerFactory and override the ReleaseController method:

public class ReleasingControllerFactory : DefaultHttpControllerFactory { private readonly Action<object> release; public ReleasingControllerFactory(Action<object> releaseCallback, HttpConfiguration configuration) : base(configuration) { this.release = releaseCallback; } public override void ReleaseController(IHttpController controller) { this.release(controller); base.ReleaseController(controller); } }

Notice that it's not necessary to override the CreateController method, since the default implementation is good enough - it'll ask the DependencyResolver for an instance of IHttpControllerActivator, which will again ask the DependencyResolver for an instance of the Controller type, in the end invoking your custom GetObject implemention.

To keep the above example generic, I just injected an Action<object> into ReleasingControllerFactory - I really don't wish to turn this into a discussion about the merits and demerits of various DI Containers. In any case, I'll leave it as an exercise to you to wire up your favorite DI Container so that the releaseCallback is actually a call to the container's Release method.

Lifetime Cycles of Infrastructure Components #

Before I conclude, I'd like to point out another POLA violation that hit me during my investigation.

The ASP.NET Web API utilizes DependencyResolver to resolve its own infrastructure types (such as IHttpControllerFactory, IHttpControllerActivator, etc.). Any custom DependencyResolver you supply will also be queried for these types. However:

When resolving infrastructure components, the Web API doesn't respect any custom lifecycle you may have defined for these components.

At a certain point while I investigated this, I wanted to configure a custom IHttpControllerActivator to have a Web Request Context (my book, section 8.3.4) - in other words, I wanted to create a new instance of IHttpControllerActivator for each incoming HTTP request.

This is not possible. The framework queries a custom DependencyResolver for an infrastructure type, but even when it receives an instance (i.e. not null), it doesn't trust the DependencyResolver to efficiently manage the lifetime of that instance. Instead, it caches this instance for ever, and never asks for it again. This is, in my opinion, a mistaken responsibility, and I hope it will be corrected in the final release.

Concluding Thoughts #

Wiring up the ASP.NET Web API with robust DI is possible, but much harder than it ought to be. Suggestions for improvements are:

- A Release hook in DependencyResolver.

- The framework itself should trust the DependencyResolver to efficiently manage lifetime of all objects it create.

As I've described, there are other places were minor adjustments would be helpful, but these two suggestions are the most important ones.

Update (2012.03.21): I've posted this feedback to the product group on uservoice and Connect - if you agree, please visit those sites and vote up the issues.

Migrating from WCF Web API to ASP.NET Web API

Now that the WCF Web API has ‘become' the ASP.NET Web API, I've had to migrate a semi-complex code base from the old to the new framework. These are my notes from that process.

Migrating Project References #

As far as I can tell, the ASP.NET Web API isn't just a port of the WCF Web API. At a cursory glance, it looks like a complete reimplementation. If it's a port of the old code, it's at least a rather radical one. The assemblies have completely different names, and so on.

Both old and new project, however, are based on NuGet packages, so it wasn't particularly hard to change.

To remove the old project references, I ran this NuGet command:

Uninstall-Package webapi.all -RemoveDependencies

followed by

Install-Package aspnetwebapi

to install the project references for the ASP.NET Web API.

Rename Resources to Controllers #

In the WCF Web API, there was no naming convention for the various resource classes. In the quickstarts, they were sometimes called Apis (like ContactsApi), and I called mine Resources (like CatalogResource). Whatever your naming convention was, the easiest things is to find them all and rename them to end with Controller (e.g. CatalogController).

AFAICT you can change the naming convention, but I didn't care enough to do so.

Derive Controllers from ApiController #

Unless you care to manually implement IHttpController, each Controller should derive from ApiController:

public class CatalogController : ApiController

Remove Attributes #

The WCF Web API uses the [WebGet] and [WebInvoke] attributes. The ASP.NET Web API, on the other hand, uses routes, so I removed all the attributes, including their UriTemplates:

//[WebGet(UriTemplate = "/")] public Catalog GetRoot()

Add Routes #

As a replacement for attributes and UriTemplates, I added HTTP routes:

routes.MapHttpRoute( name: "DefaultApi", routeTemplate: "{controller}/{id}", defaults: new { controller = "Catalog", id = RouteParameter.Optional } );

The MapHttpRoute method is an extension method defined in the System.Web.Http namespace, so I had to add a using directive for it.

Composition #

Wiring up Controllers with Constructor Injection turned out to be rather painful. For a starting point, I used Nikos Baxevanis' guide, but it turns out there are further subtleties which should be addressed (more about this later, but to prevent a stream of comments about the DependencyResolver API: yes, I know about that, but it's inadequate for a number of reasons).

Media Types #

In the ASP.NET Web API application/json is now the default media type format if the client doesn't supply any Accept header. For the WCF Web API I had to resort to a hack to change the default, so this was a pleasant surprise.

It's still pretty easy to add more supported media types:

GlobalConfiguration.Configuration.Formatters.XmlFormatter .SupportedMediaTypes.Add( new MediaTypeHeaderValue("application/vnd.247e.artist+xml")); GlobalConfiguration.Configuration.Formatters.JsonFormatter .SupportedMediaTypes.Add( new MediaTypeHeaderValue("application/vnd.247e.artist+json"));

(Talk about a Law of Demeter violation, BTW...)

However, due to an over-reliance on global state, it's not so easy to figure out how one would go about mapping certain media types to only a single Controller. This was much easier in the WCF Web API because it was possible to assign a separate configuration instance to each Controller/Api/Resource/Service/Whatever... This, I've still to figure out how to do...

Comments

webapi prev6 seems much batter than current beta

http://code.msdn.microsoft.com/Contact-Manager-Web-API-0e8e373d/view/Discussions

see Daniel reply to my post

Implementing an Abstract Factory

Abstract Factory is a tremendously useful pattern when used with Dependency Injection (DI). While I've repeatedly described how it can be used to solve various problems in DI, apparently I've never described how to implement one. As a comment to an older blog post of mine, Thomas Jaskula asks how I'd implement the IOrderShipperFactory.

To stay consistent with the old order shipper scenario, this blog post outlines three alternative ways to implement the IOrderShipperFactory interface.

To make it a bit more challenging, the implementation should create instances of the OrderShipper2 class, which itself has a dependency:

public class OrderShipper2 : IOrderShipper { private readonly IChannel channel; public OrderShipper2(IChannel channel) { if (channel == null) throw new ArgumentNullException("channel"); this.channel = channel; } public void Ship(Order order) { // Ship the order and // raise a domain event over this.channel } }

In order to be able to create an instance of OrderShipper2, any factory implementation must be able to supply an IChannel instance.

Manually Coded Factory #

The first option is to manually wire up the OrderShipper2 instance within the factory:

public class ManualOrderShipperFactory : IOrderShipperFactory { private readonly IChannel channel; public ManualOrderShipperFactory(IChannel channel) { if (channel == null) throw new ArgumentNullException("channel"); this.channel = channel; } public IOrderShipper Create() { return new OrderShipper2(this.channel); } }

This has the advantage that it's easy to understand. It can be unit tested and implemented in the same library that also contains OrderShipper2 itself. This means that any client of that library is supplied with a read-to-use implementation.

The disadvantage of this approach is that if/when the constructor of OrderShipper2 changes, the ManualOrderShipperFactory class must also be corrected. Pragmatically, this may not be a big deal, but one could successfully argue that this violates the Open/Closed Principle.

Container-based Factory #

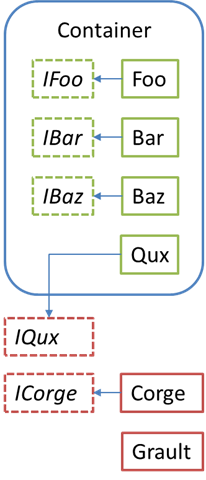

Another option is to make the implementation a thin Adapter over a DI Container - in this example Castle Windsor:

public class ContainerFactory : IOrderShipperFactory { private IWindsorContainer container; public ContainerFactory(IWindsorContainer container) { if (container == null) throw new ArgumentNullException("container"); this.container = container; } public IOrderShipper Create() { return this.container.Resolve<IOrderShipper>(); } }

But wait! Isn't this an application of the Service Locator anti-pattern? Not if this class is part of the Composition Root.

If this implementation was placed in the same library as OrderShipper2 itself, it would mean that the library would have a hard dependency on the container. In such a case, it would certainly be a Service Locator.

However, when a Composition Root already references a container, it makes sense to place the ContainerFactory class there. This changes its role to the pure infrastructure component it really ought to be. This seems more SOLID, but the disadvantage is that there's no longer a ready-to-use implementation packaged together with the LazyOrderShipper2 class. All new clients must supply their own implementation.

Dynamic Proxy #

The third option is to basically reduce the principle behind the container-based factory to its core. Why bother writing even a thin Adapter if one can be automatically generated.

With Castle Windsor, the Typed Factory Facility makes this possible:

container.AddFacility<TypedFactoryFacility>(); container.Register(Component .For<IOrderShipperFactory>() .AsFactory()); var factory = container.Resolve<IOrderShipperFactory>();

There is no longer any code which implements IOrderShipperFactory. Instead, a class conceptually similar to the ContainerFactory class above is dynamically generated and emitted at runtime.

While the code never materializes, conceptually, such a dynamically emitted implementation is still part of the Composition Root.

This approach has the advantage that it's very DRY, but the disadvantages are similar to the container-based implementation above: there's no longer a ready-to-use implementation. There's also the additional disadvantage that out of the three alternative here outlined, the proxy-based implementation is the most difficult to understand.

Comments

But i have a question. What if object, created by factory, implements IDisposable? Where we should call Dispose()?

Sorry for my English...

Often, when I open this blog from the google search results page, javascript function "highlightWord" hangs my Firefox. Probably too big cycle on DOM.

You can read more about this in chapter 6 in my book.

Regarding the bug report: thanks - I've noticed it too, but didn't know what to do about it...

You have cleand up my doubts with this sentence "But wait! Isn’t this an application of the Service Locator anti-pattern? Not if this class is part of the Composition Root." I was not just confortable about if it's well done or not.

I use also Dynamic Proxy factory because it's a great feature.

Thomas

I thought about this "life time" problem. And I've got an idea.

What if we let a concrete factory to implement the IDisposable interface?

In factory.Create method we will push every resolved service into the HashSet.

In factory.Dispose method we will call container.Release method for each object in HashSet.

Then we register our factory with a short life time, like Transitional.

So the container will release services, created by factory, as soon as possible.

What do you think about it?

About bug in javascript ...

Now the DOM visitor method "highlightWord" called for each word. It is very slow. And empty words, which passed into visitor, caused the creation of many empty SPAN elements. It is much slower.

I allowed myself to rewrite your functions... Just replace it with the following code.

var googleSearchHighlight = function () {

if (!document.createElement) return;

ref = document.referrer;

if (ref.indexOf('?') == -1 || ref.indexOf('/') != -1) {

if (document.location.href.indexOf('PermaLink') != -1) {

if (ref.indexOf('SearchView.aspx') == -1) return;

}

else {

//Added by Scott Hanselman

ref = document.location.href;

if (ref.indexOf('?') == -1) return;

}

}

//get all words

var allWords = [];

qs = ref.substr(ref.indexOf('?') + 1);

qsa = qs.split('&');

for (i = 0; i < qsa.length; i++) {

qsip = qsa[i].split('=');

if (qsip.length == 1) continue;

if (qsip[0] == 'q' || qsip[0] == 'p') { // q= for Google, p= for Yahoo

words = decodeURIComponent(qsip[1].replace(/\+/g, ' ')).split(/\s+/);

for (w = 0; w < words.length; w++) {

var word = words[w];

if (word.length)

allWords.push(word);

}

}

}

//pass words into DOM visitor

if(allWords.length)

highlightWord(document.getElementsByTagName("body")[0], allWords);

}

var highlightWord = function (node, allWords) {

// Iterate into this nodes childNodes

if (node.hasChildNodes) {

var hi_cn;

for (hi_cn = 0; hi_cn < node.childNodes.length; hi_cn++) {

highlightWord(node.childNodes[hi_cn], allWords);

}

}

// And do this node itself

if (node.nodeType == 3) { // text node

//do words iteration

for (var w = 0; w < allWords.length; w++) {

var word = allWords[w];

if (!word.length)

continue;

tempNodeVal = node.nodeValue.toLowerCase();

tempWordVal = word.toLowerCase();

if (tempNodeVal.indexOf(tempWordVal) != -1) {

pn = node.parentNode;

if (pn && pn.className != "searchword") {

// word has not already been highlighted!

nv = node.nodeValue;

ni = tempNodeVal.indexOf(tempWordVal);

// Create a load of replacement nodes

before = document.createTextNode(nv.substr(0, ni));

docWordVal = nv.substr(ni, word.length);

after = document.createTextNode(nv.substr(ni + word.length));

hiwordtext = document.createTextNode(docWordVal);

hiword = document.createElement("span");

hiword.className = "searchword";

hiword.appendChild(hiwordtext);

pn.insertBefore(before, node);

pn.insertBefore(hiword, node);

pn.insertBefore(after, node);

pn.removeChild(node);

}

}

}

}

}

I upload .js file here http://rghost.ru/37057487

Granted, if the constructor to OrderShipper2 changes, you MUST modify the abstract factory. However, isn't modifying the constructor of OrderShipper2 itself a violation of the OCP? If you are adding new dependencies, you are probably making a significant change.

At that point, you would just create a new implementation of IOrderShipper.

(Thank you very much for your assistance with the javascript - I didn't even know which particular script was causing all that trouble. Unfortunately, the script itself is compiled into the dasBlog engine which hosts this blog, so I can't change it. However, I think I managed to switch it off... Yet another reason to find myself a new blog platform...)

Btw, another thing I think about is the abstract factory's responsibility. If factory consumer can create service with the factory.Create method, maybe we should let it to destroy object with the factory.Destroy method too? Piece of the life time management moves from one place to another. Factory consumer takes responsibility for the life time (defines new scope). For example we have ControllerFactory in ASP.NET MVC. It has the Release method for this.

In other words, why not to add the Release method into the abstract factory?

However, what if we have a desktop application or a long-running batch job? How do we define an implicit scope then? One option might me to employ a timeout, but I'll have to think more about this... Not a bad idea, though :)

But for a single long-lived thread we have to invent something.

It seems that there is no silver bullet in the management of a lifetime. At least without using Resolve-Release pattern in several places instead of one ...

Can you write another book on this subject? :)

A Task<T>, on the other, provides us with the ability to attach a continuation, so that seems to me to be an appropriate candidate...

Or you could register the container with itself, enabling it to auto-wire itself.

None of these options are particularly nice, which is why I instead tend to prefer one of the other options described above.

Julien, thank you for your question. Using a Dynamic Proxy is an implementation detail. The consumer (in this case LazyOrderShipper2) depends only on IOrderShipperFactory.

Does using a Dynamic Proxy make it harder to swap containers? Yes, it does, because I'm only aware of one .NET DI Container that has this capability (although it's a couple of years ago since I last surveyed the .NET DI Container landscape). Therefore, if you start out with Castle Windsor, and then later on decide to exchange it for another DI Container, you would have to supply a manually coded implementation of IOrderShipperFactory. You could choose to implement either a Manually Coded Factory, or a Container-based Factory, as described in this article. It's rather trivial to do, so I would hardly call it blocking issue.

The more you rely on specific features of a particular DI Container, the more work you'll have to perform to migrate. This is why I always recommend that you design your classes following normal, good design practices first, without any regard to how you'd use them with any particular DI Container. Only when you've designed your API should you figure out how to compose it with a DI Container (if at all).

Personally, I don't find container verification particularly valuable, but then again, I mostly use Pure DI anyway.

Is Layering Worth the Mapping?

For years, layered application architecture has been a de-facto standard for loosely coupled architectures, but the question is: does the layering really provide benefit?

In theory, layering is a way to decouple concerns so that UI concerns or data access technologies don't pollute the domain model. However, this style of architecture seems to come at a pretty steep price: there's a lot of mapping going on between the layers. Is it really worth the price, or is it OK to define data structures that cut across the various layers?

The short answer is that if you cut across the layers, it's no longer a layered application. However, the price of layering may still be too high.

In this post I'll examine the problem and the proposed solution and demonstrate why none of them are particularly good. In the end, I'll provide a pointer going forward.

Proper Layering #

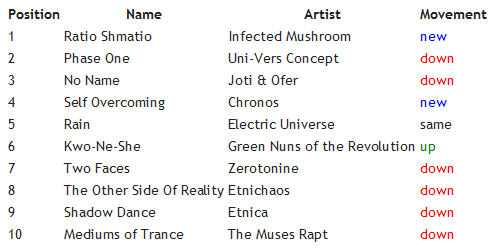

To understand the problem with layering, I'll describe a fairly simple example. Assume that you are building a music service and you've been asked to render a top 10 list for the day. It would have to look something like this in a web page:

As part of rendering the list, you must color the Movement values accordingly using CSS.

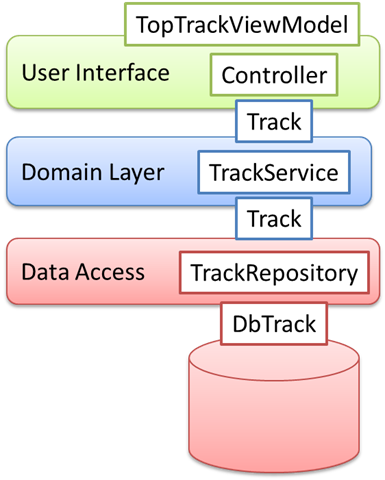

A properly layered architecture would look something like this:

Each layer defines some services and some data-carrying classes (Entities, if you want to stick with the Domain-Driven Design terminology). The Track class is defined by the Domain layer, while the TopTrackViewModel class is defined in the User Interface layer, and so on. If you are wondering about why Track is used to communicate both up and down, this is because the Domain layer should be the most decoupled layer, so the other layers exist to serve it. In fact, this is just a vertical representation of the Ports and Adapters architecture, with the Domain Model sitting in the center.

This architecture is very decoupled, but comes at the cost of much mapping and seemingly redundant repetition. To demonstrate why that is, I'm going to show you some of the code. This is an ASP.NET MVC application, so the Controller is an obvious place to start:

public ViewResult Index() { var date = DateTime.Now.Date; var topTracks = this.trackService.GetTopFor(date); return this.View(topTracks); }

This doesn't look so bad. It asks an ITrackService for the top tracks for the day and returns a list of TopTrackViewModel instances. This is the implementation of the track service:

public IEnumerable<TopTrackViewModel> GetTopFor( DateTime date) { var today = DateTime.Now.Date; var yesterDay = today - TimeSpan.FromDays(1); var todaysTracks = this.repository.GetTopFor(today).ToList(); var yesterdaysTracks = this.repository.GetTopFor(yesterDay).ToList(); var length = todaysTracks.Count; var positions = Enumerable.Range(1, length); return from tt in todaysTracks.Zip( positions, (t, p) => new { Position = p, Track = t }) let yp = (from yt in yesterdaysTracks.Zip( positions, (t, p) => new { Position = p, Track = t }) where yt.Track.Id == tt.Track.Id select yt.Position) .DefaultIfEmpty(-1) .Single() let cssClass = GetCssClass(tt.Position, yp) select new TopTrackViewModel { Position = tt.Position, Name = tt.Track.Name, Artist = tt.Track.Artist, CssClass = cssClass }; } private static string GetCssClass( int todaysPosition, int yesterdaysPosition) { if (yesterdaysPosition < 0) return "new"; if (todaysPosition < yesterdaysPosition) return "up"; if (todaysPosition == yesterdaysPosition) return "same"; return "down"; }

While that looks fairly complex, there's really not a lot of mapping going on. Most of the work is spent getting the top 10 track for today and yesterday. For each position on today's top 10, the query finds the position of the same track on yesterday's top 10 and creates a TopTrackViewModel instance accordingly.

Here's the only mapping code involved:

select new TopTrackViewModel { Position = tt.Position, Name = tt.Track.Name, Artist = tt.Track.Artist, CssClass = cssClass };

This maps from a Track (a Domain class) to a TopTrackViewModel (a UI class).

This is the relevant implementation of the repository:

public IEnumerable<Track> GetTopFor(DateTime date) { var dbTracks = this.GetTopTracks(date); foreach (var dbTrack in dbTracks) { yield return new Track( dbTrack.Id, dbTrack.Name, dbTrack.Artist); } }

You may be wondering about the translation from DbTrack to Track. In this case you can assume that the DbTrack class is a class representation of a database table, modeled along the lines of your favorite ORM. The Track class, on the other hand, is a proper object-oriented class which protects its invariants:

public class Track { private readonly int id; private string name; private string artist; public Track(int id, string name, string artist) { if (name == null) throw new ArgumentNullException("name"); if (artist == null) throw new ArgumentNullException("artist"); this.id = id; this.name = name; this.artist = artist; } public int Id { get { return this.id; } } public string Name { get { return this.name; } set { if (value == null) throw new ArgumentNullException("value"); this.name = value; } } public string Artist { get { return this.artist; } set { if (value == null) throw new ArgumentNullException("value"); this.artist = value; } } }

No ORM I've encountered so far has been able to properly address such invariants - particularly the non-default constructor seems to be a showstopper. This is the reason a separate DbTrack class is required, even for ORMs with so-called POCO support.

In summary, that's a lot of mapping. What would be involved if a new field is required in the top 10 table? Imagine that you are being asked to provide the release label as an extra column.

- A Label column must be added to the database schema and the DbTrack class.

- A Label property must be added to the Track class.

- The mapping from DbTrack to Track must be updated.

- A Label property must be added to the TopTrackViewModel class.

- The mapping from Track to TopTrackViewModel must be updated.

- The UI must be updated.

That's a lot of work in order to add a single data element, and this is even a read-only scenario! Is it really worth it?

Cross-Cutting Entities #

Is strict separation between layers really so important? What would happen if Entities were allowed to travel across all layers? Would that really be so bad?

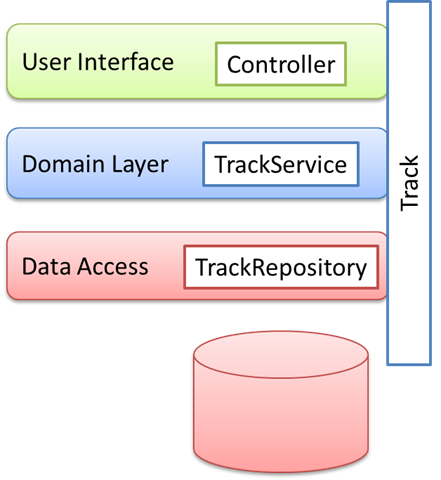

Such an architecture is often drawn like this:

Now, a single Track class is allowed to travel from layer to layer in order to avoid mapping. The controller code hasn't really changed, although the model returned to the View is no longer a sequence of TopTrackViewModel, but simply a sequence of Track instances:

public ViewResult Index() { var date = DateTime.Now.Date; var topTracks = this.trackService.GetTopFor(date); return this.View(topTracks);}

The GetTopFor method also looks familiar:

public IEnumerable<Track> GetTopFor(DateTime date) { var today = DateTime.Now.Date; var yesterDay = today - TimeSpan.FromDays(1); var todaysTracks = this.repository.GetTopFor(today).ToList(); var yesterdaysTracks = this.repository.GetTopFor(yesterDay).ToList(); var length = todaysTracks.Count; var positions = Enumerable.Range(1, length); return from tt in todaysTracks.Zip( positions, (t, p) => new { Position = p, Track = t }) let yp = (from yt in yesterdaysTracks.Zip( positions, (t, p) => new { Position = p, Track = t }) where yt.Track.Id == tt.Track.Id select yt.Position) .DefaultIfEmpty(-1) .Single() let cssClass = GetCssClass(tt.Position, yp) select Enrich( tt.Track, tt.Position, cssClass); } private static string GetCssClass( int todaysPosition, int yesterdaysPosition) { if (yesterdaysPosition < 0) return "new"; if (todaysPosition < yesterdaysPosition) return "up"; if (todaysPosition == yesterdaysPosition) return "same"; return "down"; } private static Track Enrich( Track track, int position, string cssClass) { track.Position = position; track.CssClass = cssClass; return track; }

Whether or not much has been gained is likely to be a subjective assessment. While mapping is no longer taking place, it's still necessary to assign a CSS Class and Position to the track before handing it off to the View. This is the responsibility of the new Enrich method:

private static Track Enrich( Track track, int position, string cssClass) { track.Position = position; track.CssClass = cssClass; return track; }

If not much is gained at the UI layer, perhaps the data access layer has become simpler? This is, indeed, the case:

public IEnumerable<Track> GetTopFor(DateTime date) { return this.GetTopTracks(date); }

If, hypothetically, you were asked to add a label to the top 10 table it would be much simpler:

- A Label column must be added to the database schema and the Track class.

- The UI must be updated.

This looks good. Are there any disadvantages? Yes, certainly. Consider the Track class:

public class Track { public int Id { get; set; } public string Name { get; set; } public string Artist { get; set; } public int Position { get; set; } public string CssClass { get; set; } }

It also looks simpler than before, but this is actually not particularly beneficial, as it doesn't protect its invariants. In order to play nice with the ORM of your choice, it must have a default constructor. It also has automatic properties. However, most insidiously, it also somehow gained the Position and CssClass properties.

What does the Position property imply outside of the context of a top 10 list? A position in relation to what?

Even worse, why do we have a property called CssClass? CSS is a very web-specific technology so why is this property available to the Data Access and Domain layers? How does this fit if you are ever asked to build a native desktop app based on the Domain Model? Or a REST API? Or a batch job?

When Entities are allowed to travel along layers, the layers basically collapse. UI concerns and data access concerns will inevitably be mixed up. You may think you have layers, but you don't.

Is that such a bad thing, though?

Perhaps not, but I think it's worth pointing out:

The choice is whether or not you want to build a layered application. If you want layering, the separation must be strict. If it isn't, it's not a layered application.

There may be great benefits to be gained from allowing Entities to travel from database to user interface. Much mapping cost goes away, but you must realize that then you're no longer building a layered application - now you're building a web application (or whichever other type of app you're initially building).

Further Thoughts #

It's a common question: how hard is it to add a new field to the user interface?

The underlying assumption is that the field must somehow originate from a corresponding database column. If this is the case, mapping seems to be in the way.

However, if this is the major concern about the application you're currently building, it's a strong indication that you are building a CRUD application. If that's the case, you probably don't need a Domain Model at all. Go ahead and let your ORM POCO classes travel up and down the stack, but don't bother creating layers: you'll be building a monolithic application no matter how hard you try not to.

In the end it looks as though none of the options outlined in this article are particularly good. Strict layering leads to too much mapping, and no mapping leads to monolithic applications. Personally, I've certainly written quite a lot of strictly layered applications, and while the separation of concerns was good, I was never happy with the mapping overhead.

At the heart of the problem is the CRUDy nature of many applications. In such applications, complex object graphs are traveling up and down the stack. The trick is to avoid complex object graphs.

Move less data around and things are likely to become simpler. This is one of the many interesting promises of CQRS, and particularly it's asymmetric approach to data.

To be honest, I wish I had fully realized this when I started writing my book, but when I finally realized what I'd implicitly felt for long, it was too late to change direction. Rest assured that nothing in the book is fundamentally flawed. The patterns etc. still hold, but the examples could have been cleaner if the sample applications had taken a CQRS-like direction instead of strict layering.

Comments

- Domain layer with rich objects and protected variations

- Commands and Command handlers (write only) acting on the domain entities

- Mapping domain layer using NHibernate (I thought at first to start by creating a different data model because of the constraints of orm on the domain, but i managed to get rid of most of them - like having a default but private constructor, and mapping private fields instead of public properties ...)

- Read model which consist of view models.

- Red model mapping layer which uses the orm to map view models to database directly (thus i got rid of mapping between view models and domains - but introduced a mapping between view models and database).

- Query objects to query the read model.

at the end of application i came to almost the same conclusion of not being happy with the mappings.

- I have to map domain model to database.

- I have to map between view models (read model) and database.

- I have to map between view models and commands.

- I have to map between commands and domain model.

- Having many fine grained commands is good in terms of defining strict behaviors and ubiquitous language but at the cost of maintainability, now when i introduce a new field most probably will have to modify a database field, domain model, view model, two data mappings for domain model and view model, 1 or more command and command handlers, and UI !

So taking the practice of CQRS for me enriched the domain a little, simplified the operations and separated it from querying, but complicated the implementation and maintenance of the application.

So I am still searching for a better approach to gain the rich domain model behavior and simplifying maintenance and eliminate mappings.

I too have felt pain of a lot of useless mapping a lot times. But even for CRUD applications where the business rules do not change much, I still almost always take the pain and do the mapping because I have a deep sitting fear of monolthic apps and code rot. If I give my entities lots of different concerns (UI, persistence, domainlogic etc.), isn't this kind of code smell the culture medium for more code smell and code rot? When evolving my application and I am faced with a quirk in my code, I often only have two choices: Add a new quirk or remove the original quirk. It kind of seems that in the long run a rotten monolithic app that his hard to maintain and extend becomes almost inevitable if I give up SoC the way you described.

Did I understand you correctly that you'd say it's OK to soften SoC a bit and let the entity travel across all layers for *some* apps? If yes, what kind of apps? Do you share my fear of inevitable code rot? How do you deal with this?

I use either convention based NH mappings which make me almost forget it's there, or MemoryImage to reconstruct my object model (the boilerplate is reduced by wrapping my objects with proxies that intercept method calls and record them as a json Event Source). In both cases I can use a helper library which wraps my objects with proxies that help protect invariants.

My web UI is built using a framework along the lines of the Naked Object a pattern*, which can be customised using ViewModels and custom views, and which enforces good REST design. This framework turns objects into pages and methods into ajax forms.

I built all this stuff after getting frustrated with the problems you mention above, inspired in part by all the time I spent at Uni trying to make games (in which an in memory domain model is rendered to the screen by a disconnected rendering engine, and input collected via a separate mechanism and applied to that model).

The long of the short of it is that I can add a field to the screen in seconds, and add a new feature in minutes. There are some trade offs, but it's great to feel like I am just writing an object model and leaving the rest to my frameworks.

*not Naked Objects MVC, a DIY library thats not ready for the public yet.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naked_objects

https://github.com/mcintyre321/NhCodeFirst my mappings lib (but Fluent NH is probably fine)

http://martinfowler.com/bliki/MemoryImage.html

https://github.com/mcintyre321/Harden my invariant helper library

The only thing I'm saying is that it's better to build a monolithic application when you know and understand that this is what you are doing, than it is to be building a monolithic application while under the illusion that you are building a decoupled application.

If there's a point in there, it's that static languages (without designers) generally don't lend well to RAD, and if RAD is what you need, you have many popular options that aren't C#.

Also, I have two problems with some of the sample code you wrote. Specifically, the Enrich method. First, a method signature such as:

T Method(T obj, ...);

Implies to consumers that the method is pure. Because this isn't the case, consumers will incorrectly use this method without the intention of modifying the original object. Second, if it is true that your ViewModels are POCOs consisting of your mapped properties AND a list of computed properties, perhaps you should instead use inheritance. This implementation is certainly SOLID:

(sorry for the formatting)

class Track

{

/* Mapped Properties */

public Track()

{

}

protected Track(Track rhs)

{

Prop1 = rhs.Prop1;

Prop2 = rhs.Prop2;

Prop3 = rhs.Prop3;

}

}

class TrackWebViewModel : Track

{

public string ClssClass { get; private set; }

public TrackWebViewModel(Track track, string cssClass) : this(track)

{

CssClass = cssClass;

}

}

let cssClass = GetCssClass(tt.Position, yp) select Enrich(tt.Track, tt.Position, cssClass)

Simply becomes

select new TrackWebViewModel(tt.Track, tt.Position, cssClass)

While your suggested, inheritance-based solution seems cleaner, please note that it also introduces a mapping (in the copy constructor). Once you start doing this, there's almost always a composition-based solution which is at least as good as the inheritance-based solution.

As far as the copy-ctor, yes, that is a mapping, but when you add a field, you just have to modify a file you're already modifying. This is a bit nicer than having to update mapping code halfway across your application. But you're right, composting a Track into a specific view model would be a nicer approach with fewer modifications required to add more view models and avoiding additional mapping.

Though, I still am a bit concerned about the architecture as a whole. I understand in this post you were thinking out loud about a possible way to reduce complexity in certain types of applications, yet I'm wondering if you had considered using a platform designed for applications like this instead of using C#. Rails is quite handy when you need CRUD.

thanks for the blog posts and DI book, which I'm currently reading over the weekend. I guess the scenario you're describing here is more or less commonplace, and as the team I'm working on are constantly bringing this subject up on the whiteboard, I thought I'd share a few thoughts on the mapping part. Letting the Track entity you're mentioning cross all layers is probably not a good idea.

I agree that one should program to interfaces. Thus, any entity (be it an entity created via LINQ to SQL, EF, any other ORM/DAL or business object) should be modeled and exposed via an interface (or hierarchy thereof) from repositories or the like. With that in mind, here's what I think of mapping between entities. Popular ORM/DALs provide support for partial entities, external mapping files, POCOs, model-first etc.

Take this simple example:

// simplified pattern (deliberately not guarding args, and more)

interface IPageEntity { string Name { get; }}

class PageEntity : IPageEntity {}

class Page : IPage

{

private IPageEntity entity;

private IStrategy strategy;

public Page(IPageEntity entity, IStrategy strategy)

{

this.entity = entity;

this.strategy = strategy;

}

public string Name

{

get { return this.entity.Name; }

set { this.strategy.CopyOnWrite(ref this.entity).Name = value; }

}

}

One of the benefits from using an ORM/DAL is that queries are strongly typed and results are projected to strongly typed entities (concrete or anonymous). They are prime candidates for embedding inside of business objects (BO) (as DTOs), as long as they implement the required interface for injected in the constructor. This is much more flexible (and clean) rather than taking a series of arguments, each corresponding to a property on the original entity. Instead of having the BO keeping private members mapped to the constructor args, and subsequently mapping public properties and methods to said members, you simply map to the entity injected in the BO.

The benefit is much greater performance (less copying of args), a consistent design pattern and a layer of indirection in your BO that allows you to capture any potential changes to your entity (such as using the copy-on-write pattern that creates an exact copy of the entity, releasing it from a potential shared cache you've created by decorating the repository, from which the entity originally was retrieved).

Again, in my example one of the goals were to make use of shared (cached) entities for high performance, while making sure that there are no side effects from changing a business object (seeing this from client code perspective).

Code following the above pattern is just as testable as the code in your example (one could argue it's even easier to write tests, and maintenance is vastly reduced). Whenever I see BO constructors taking huge amounts of args I cry blood.

In my experience, this allows a strictly layered application to thrive without the mapping overhead.

Your thoughts?

What do you propose in cases when you have a client server application with request/response over WCF and the domain model living on the server? Is there a better way than for example mapping from NH entities to DataContracts and from DataContracts to ViewModels?

Thnaks for the post!

"... asks an ITrackService for the top tracks for the day and returns a list of TopTrackViewModel instances..."

The diagram really makes it look like the TrackService returns Track objects to the Controller and the Controller maps them into TopTrackViewModel objects. If that is the case... how would you communicate the Position and CssClass properties that the Domain Layer has computed between the two layers?

Also, I noticed that ITrackService.GetTopFor(DateTime date) never uses the input parameter... should it really be more like ITrackService.GetTopForToday() instead?

Awesome blog! Is there an email address I can contact you in private?

If the service layer exists in order to decouple the service from the client, you must translate from the internal model to a service API. However, if this is the case, keep in mind that at the service boundary, you are no longer dealing with objects at all, so translation or mapping is conceptually very important. If you have .NET on both sides it's easy to lose sight of this, but imagine that either service or client is implemented in COBOL and you may begin to understand the importance of translation.

So as always, it's a question of evaluating the advantages and disadvantages of each alternative in the concrete situation. There's no one correct answer.

Personally, I'm beginning to consider ORMs the right solution to the wrong problem. A relational database is rarely the correct data store for a LoB application or your typical web site.

Pardon me if I've gotten this wrong, because I'm approaching your post as an actionscript developer who is entirely self-taught. I don't know C#, but I like to read posts on good design from whatever language.

How I might resolve this problem is to create a TrackDisplayModel Class that wraps the Track Class and provides the "enriched" methods of the position and cssClass. In AS, we have something called a Proxy Class that allows us to "repeat" methods on an inner object without writing a lot of code, so you could pass through the properties of the Track by making TrackDisplayModel extend Proxy. By doing this, I'd give up code completion and type safety, so I might not find that long term small cost worth the occasional larger cost of adding a field in more conventional ways.

Does C# have a Class that is like Proxy that could be used in this way?

No matter how you'd achieve such things, I'm not to happy about doing this, as most of the variability axes we get from a multi-paradigmatic language such as C# is additive - it means that while it's fairly easy to add new capabilities to objects, it's actually rather hard to remove capabilities.

When we map from e.g. a domain model to a UI model, we should consider that we must be able to do both: add as well as subtract behavior. There may be members in our domain model we don't want the UI model to use.

Also, when the application enables the user to write as well as read data, we must be able to map both ways, so this is another reason why we must be able to add as well as remove members when traversing layers.

I'm not saying that a dynamic approach isn't viable - in fact, I find it attractive in various scenarios. I'm just saying that simply exposing a lower-level API to upper layers by adding more members to it seems to me to go against the spirit of the Single Responsibility Principle. It would just be tight coupling on the semantic level.

You might also want to refer to my answer to Amy immediately above. The data structures the UI requires may be entirely different from the Domain Model, which again could be different from the data access model. The UI will often be an aggregate of data from many different data sources.

In fact, I'd consider it a code smell if you could get by with the same data structure in all layers. If one can do that, one is most likely building a CRUD application, in which case a monolithic RAD application might actually be a better architectural choice.

You've mentioned in your blogs (here and elsewhere) and on stackoverflow simliar sentiments to your last comment:

<blockquote>

I'd consider it a code smell if you could get by with the same data structure in all layers. If one can do that, one is most likely building a CRUD application, in which case a monolithic RAD application might actually be a better architectural choice.

</blockquote>

Most line of business (LoB) apps consist of CRUD operations. As such, when does an LoB app cross the line from being strictly "CRUDy" and jumps into the realm where where layering (or using CQRS) is preferable? Could you expand on your definition of building a CRUD application?

What I think would be the correct thing, on the other hand, would be to make a conscious decision as a team on which way to go. If the team agrees that the project is most likely a CRUD application, then it can save itself the trouble of having all those layers. However, it's very important to stress to non-technical team members and stake holders (project managers etc.) that there's a trade-off here: We've decided to go with RAD development. This will enables us to go fast as long as our assumption about a minimum of business logic holds true. On the other hand, if that assumption fails, we'll be going very slowly. Put it in writing and make sure those people understand this.

You can also put it another way: creating a correctly layered application is slow, but relatively safe. Assuming that you know what you're doing with layering (lots of people don't), developing a layered application removes much of that risk. Such an architecture is going to be able to handle a lot of the changes you'll throw at it, but it'll be slow going.

HTH

If youre 'referring to the case where there is actually a domain to model, then CQRS (the concept) is easily the answer. However, even in such app you'd have some parts which are CRUD. I simply like to use the appropriate tool for the job. For complex Aggregate Roots, Event Sourcing simplifies storage a lot. For 'dumb' objects, directly CRUD stuff. Of course, everything is done via a repository.

Now, for complex domain I'd also use a message driven architecture so I'd have Domain events with handlers which will generate any read model required. I won't really have a mapping problem as event sourcing will solve it for complex objects while for simple objects at most I'll automap or use the domain entities directly .

Nice blog!

All the mapping stems from querying/reading the domain model. I have come to the conclusion that this is what leads to all kinds of problems such as:

- lazy loading

- mapping

- fetching strategies

The domain model has state but should *do* stuff. As you stated, the domain needs highly cohesive aggregates to get the object graph a short as possible. I do not use an ORM (I do my own mapping) so I do not have ORM specific classes.

So I am 100% with you on the CQRS. There are different levels to doing CQRS and I think many folks shy away from it because they think there is only the all-or-nothing asynchronous messaging way to get to CQRS. Yet there are various approaches depending on the need, e.g.:-

All within the same transaction scope with no messaging (100% consistent):

- store read data in same table (so different columns) <-- probably the most typical option in this scenario

- store read data in separate table in the same database

- store read data in another table in another database

Using eventual consistency via messaging / service bus (such as Shuttle - http://shuttle.codeplex.com/ | MassTransit | NServiceBus):

- store read data in same table (so different columns)

- store read data in separate table in the same database

- store read data in another table in another database <-- probably the most typical option in this scenario

Using C# I would return the data from my query layer as a DataRow or DataTable and in the case of something more complex a DTO.

Regards,

Eben

Loose Coupling and the Big Picture

A common criticism of loosely coupled code is that it's harder to understand. How do you see the big picture of an application when loose coupling is everywhere? When the entire code base has been programmed against interfaces instead of concrete classes, how do we understand how the objects are wired and how they interact?

In this post, I'll provide answers on various levels, from high-level architecture over object-oriented principles to more nitty-gritty code. Before I do that, however, I'd like to pose a set of questions you should always be prepared to answer.

Mu #

My first reaction to that sort of question is: you say loosely coupled code is harder to understand. Harder than what?

If we are talking about a non-trivial application, odds are that it's going to take some time to understand the code base - whether or not it's loosely coupled. Agreed: understanding a loosely coupled code base takes some work, but so does understanding a tightly coupled code base. The question is whether it's harder to understand a loosely coupled code base?

Imagine that I'm having a discussion about this subject with Mary Rowan from my book.

Mary: “Loosely coupled code is harder to understand.”

Me: “Why do you think that is?”

Mary: “It's very hard to navigate the code base because I always end up at an interface.”

Me: “Why is that a problem?”

Mary: “Because I don't know what the interface does.”

At this point I'm very tempted to answer Mu. An interfaces doesn't do anything - that's the whole point of it. According to the Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP), a consumer shouldn't have to care about what happens on the other side of the interface.

However, developers used to tightly coupled code aren't used to think about services in this way. They are used to navigate the code base from consumer to service to understand how the two of them interact, and I will gladly admit this: in principle, that's impossible to do in a loosely coupled code base. I'll return to this subject in a little while, but first I want to discuss some strategies for understanding a loosely coupled code base.

Architecture and Documentation #

Yes: documentation. Don't dismiss it. While I agree with Uncle Bob and like-minded spirits that the code is the documentation, a two-page document that outlines the Big Picture might save you from many hours of code archeology.

The typical agile mindset is to minimize documentation because it tends to lose touch with the code base, but even so, it should be possible to maintain a two-page high-level document so that it stays up to date. Consider the alternative: if you have so much architectural churn that even a two-page overview regularly falls behind, then you're probably having a greater problem than understanding your loosely coupled code base.

Maintaining such a document isn't adverse to the agile spirit. You'll find the same advice in Lean Architecture (p. 127). Don't underestimate the value of such a document.

See the Forest Instead of the Trees #

Understanding a loosely coupled code base typically tends to require a shift of mindset.

Recall my discussion with Mary Rowan. The criticism of loose coupling is that it's difficult to understand which collaborators are being invoked. A developer like Mary Rowan is used to learn a code base by understanding all the myriad concrete details of it. In effect, while there may be ‘classes' around, there are no abstractions in place. In order to understand the behavior of a user interface element, it's necessary to also understand what's happening in the database - and everything in between.

A loosely coupled code base shouldn't be like that.

The entire purpose of loose coupling is that we should be able to reason about a part (a ‘unit', if you will) without understanding the whole.

In a tightly coupled code base, it's often impossible to see the forest for the trees. Although we developers are good at relating to details, a tightly coupled code base requires us to be able to contain the entire code base in our heads in order to understand it. As the size of the code base grows, this becomes increasingly difficult.

In a loosely coupled code base, on the other hand, it should be possible to understand smaller parts in isolation. However, I purposely wrote “should be”, because that's not always the case. Often, a so-called “loosely coupled” code base violates basic principles of object-oriented design.

RAP #

The criticism that it's hard to see “what's on the other side of an interface” is, in my opinion, central. It betrays a mindset which is still tightly coupled.

In many code bases there's often a single implementation of a given interface, so developers can be forgiven if they think about an interface as only a piece of friction that prevents them from reaching the concrete class on the other side. However, if that's the case with most of the interfaces in a code base, it signifies a violation of the Reused Abstractions Principle (RAP) more than it signifies loose coupling.

Jim Cooper, a reader of my book, put it quite eloquently on the book's forum:

“So many people think that using an interface magically decouples their code. It doesn't. It only changes the nature of the coupling. If you don't believe that, try changing a method signature in an interface - none of the code containing method references or any of the implementing classes will compile. I call that coupled”

Refactoring tools aside, I completely agree with this statement. The RAP is a test we can use to verify whether or not an interface is truly reusable - what better test is there than to actually reuse your interfaces?

The corollary of this discussion is that if a code base is massively violating the RAP then it's going to be hard to understand. It has all the disadvantages of loose coupling with few of the benefits. If that's the case, you would gain more benefit from making it either more tightly coupled or truly loosely coupled.

What does “truly loosely coupled” mean?

LSP #

According to the LSP a consumer must not concern itself with “what's on the other side of the interface”. It should be possible to replace any implementation with any other implementation of the same interface without changing the correctness of the program.

This is why I previously said that in a truly loosely coupled code base, it isn't ‘hard' to understand “what's on the other side of the interface” - it's impossible. At design-time, there's nothing ‘behind' the interface. The interface is what you are programming against. It's all there is.

Mary has been listening to all of this, and now she protests:

Mary: “At run-time, there's going to be a concrete class behind the interface.”

Me (being annoyingly pedantic): “Not quite. There's going to be an instance of a concrete class which the consumer invokes via the interface it implements.”

Mary: “Yes, but I still need to know which concrete class is going to be invoked.”

Me: “Why?”

Mary: “Because otherwise I don't know what's going to happen when I invoke the method.”

This type of answer often betrays a much more fundamental problem in a code base.

CQS #

Now we are getting into the nitty-gritty details of class design. What would you expect that the following method does?

public List<Order> GetOpenOrders(Customer customer)

The method name indicates that it gets open orders, and the signature seems to back it up. A single database query might be involved, since this looks a lot like a read-operation. A quick glance at the implementation seems to verify that first impression:

public List<Order> GetOpenOrders(Customer customer) { var orders = GetOrders(customer); return (from o in orders where o.Status == OrderStatus.Open select o).ToList(); }

Is it safe to assume that this is a side-effect-free method call? As it turns out, this is far from the case in this particular code base:

private List<Order> GetOrders(Customer customer) { var gw = new CustomerGateway(this.ConnectionString); var orders = gw.GetOrders(customer); AuditOrders(orders); FixCustomer(gw, orders, customer); return orders; }

The devil is in the details. What does AuditOrders do? And what does FixCustomer do? One method at a time:

private void AuditOrders(List<Order> orders) { var user = Thread.CurrentPrincipal.Identity.ToString(); var gw = new OrderGateway(this.ConnectionString); foreach (var o in orders) { var clone = o.Clone(); var ar = new AuditRecord { Time = DateTime.Now, User = user }; clone.AuditTrail.Add(ar); gw.Update(clone); // We don't want the consumer to see the audit trail. o.AuditTrail.Clear(); } }

OK, it turns out that this method actually makes a copy of each and every order and updates that copy, writing it back to the database in order to leave behind an audit trail. It also mutates each order before returning to the caller. Not only does this method result in an unexpected N+1 problem, it also mutates its input, and perhaps even more surprising, it's leaving the system in a state where the in-memory object is different from the database. This could lead to some pretty interesting bugs.

Then what happens in the FixCustomer method? This:

// Fixes the customer status field if there were orders // added directly through the database. private static void FixCustomer(CustomerGateway gw, List<Order> orders, Customer customer) { var total = orders.Sum(o => o.Total); if (customer.Status != CustomerStatus.Preferred && total > PreferredThreshold) { customer.Status = CustomerStatus.Preferred; gw.Update(customer); } }

Another potential database write operation, as it turns out - complete with an apology. Now that we've learned all about the details of the code, even the GetOpenOrders method is beginning to look suspect. The GetOrders method returns all orders, with the side effect that all orders were audited as having been read by the user, but the GetOpenOrders filters the output. In the end, it turns out that we can't even trust the audit trail.

While I must apologize for this contrived example of a Transaction Script, it's clear that when code looks like that, it's no wonder why developers think that it's necessary to contain the entire code base in their heads. When this is the case, interfaces are only in the way.

However, this is not the fault of loose coupling, but rather a failure to adhere to the very fundamental principle of Command-Query Separation (CQS). You should be able to tell from the method signature alone whether invoking the method will or will not have side-effects. This is one of the key messages from Clean Code: the method name and signature is an abstraction. You should be able to reason about the behavior of the method from its declaration. You shouldn't have to read the code to get an idea about what it does.

Abstractions always hide details. Method declarations do too. The point is that you should be able to read just the method declaration in order to gain a basic understanding of what's going on. You can always return to the method's code later in order to understand detail, but reading the method declaration alone should provide the Big Picture.

Strictly adhering to CQS goes a long way in enabling you to understand a loosely coupled code base. If you can reason about methods at a high level, you don't need to see “the other side of the interface” in order to understand the Big Picture.

Stack Traces #

Still, even in a loosely coupled code base with great test coverage, integration issues arise. While each class works fine in isolation, when you integrate them, sometimes the interactions between them cause errors. This is often because of incorrect assumptions about the collaborators, which often indicates that the LSP was somehow violated.

To understand why such errors occur, we need to understand which concrete classes are interacting. How do we do that in a loosely coupled code base?

That's actually easy: look at the stack trace from your error report. If your error report doesn't include a stack trace, make sure that it's going to do that in the future.

The stack trace is one of the most important troubleshooting tools in a loosely coupled code base, because it's going to tell you exactly which classes were interacting when an exception was thrown.

Furthermore, if the code base also adheres to the Single Responsibility Principle and the ideals from Clean Code, each method should be very small (under 15 lines of code). If that's the case, you can often understand the exact nature of the error from the stack trace and the error message alone. It shouldn't even be necessary to attach a debugger to understand the bug, but in a pinch, you can still do that.

Tooling #

Returning to the original question, I often hear people advocating tools such as IDE add-ins which support navigation across interfaces. Such tools might provide a menu option which enables you to “go to implementation”. At this point it should be clear that such a tool is mainly going to be helpful in code bases that violate the RAP.

(I'm not naming any particular tools here because I'm not interested in turning this post into a discussion about the merits of various specific tools.)

Conclusion #

It's the responsibility of the loosely coupled code base to make sure that it's easy to understand the Big Picture and that it's easy to work with. In the end, that responsibility falls on the developers who write the code - not the developer who's trying to understand it.

Comments

Thomas

You can argue that the most important consumer is the production code and I definitely agree with you! But let's not underestimate the role and the importance of the automated test as this is the only consumer that should drive the design of your API.

I'm a big proponent of the concept that, with TDD, unit tests are actually the first consumer of your code, and the final application only a close second. As such, it may seem compelling to state that you're never breaking the RAP if you do TDD. However, as a knee-jerk reaction, I just don't buy that argument, which made me think why that is the case...

I haven't thought this completely through yet, but I think many (not all) unit tests pose a special case. A very specialized Test Double isn't really a piece of reuse as much as it's a simulation of the production environment. Add into this mix any dynamic mock library, and you have a tool where you can simulate anything.

However, simulation isn't the same as reuse.

I think a better test would be if you can write a robust and maintainable Fake. If you can do that, the abstraction is most likely reuseable. If not, it probably isn't.

Thanks,

Thomas

In any case, please refer back to the original definition of the RAP. It doesn't say that you aren't allowed to program against 1:1 interfaces - it just states that as long as it remains a 1:1 interface, you haven't proved that it's a generalization. Until that happens, it should be treated as suspect.

However, the RAP states that we should discover generalizations after the fact, which implies that we'd always have to go through a stage where we have 1:1 interfaces. As part of the Refactoring step of Red/Green/Refactor, it should be our responsibility to merge interfaces, just as it's our responsibility to remove code duplication.

1. RAP says that using an interface that has only one implementation is unnecessary.

2. Dependency inversion principle states that both client and service should depend on an abstraction.

3. Tight coupling is discouraged and often defined as depending on a class (i.e. "newing" up a class for use).

So in order to depend on an abstraction (I understand that "abstraction" does not necessarily mean interface all of the time), you need to create an interface and program to it. If you create an interface for this purpose but it only has one implementation than it is suspect under RAP. I understand also that RAP also refers to pointless interfaces such as "IPerson" that has a Person class as an implementation or "IProduct" that has one Product implementation.

But how about a controller that needs a business service or a business service that needs a data service? I find it easier to build a business service in isolation from a data service or controller so I create an interface for the data services I need but don't create implementations. Then I just mock the interfaces to make sure that my business service works through unit testing. Then I move on to the next layer, making sure that the services then implement the interface defined by the business layer. Thoughts? Opinions?

Remember that with TDD we should move through the three phases of Red, Green and Refactor. During the Refactoring phase we typically look towards eliminating duplication. We are (or at least should be) used to do this for code duplication. The only thing the RAP states is that we should extend that effort towards our interface designs.

Please also refer to the other comment on this page.

HTH

I think one thing to consider in the whole loose coupling debate is granularity.

Not too many people talk about granularity, and without that aspect, I think it is impossible to really have enough context to say whether something is too tightly or loosely coupled. I wrote about the idea here: http://simpleprogrammer.com/2010/11/09/back-to-basics-cohesion-and-coupling-part-2/

Essentially what I am saying is that some things should be coupled. We don't want to create unneeded abstractions, because they introduce complexity. The example I use is Enterprise FizzBuzz. At the same time, we should be striving to build the seams at the points of change which should align in a well designed system with responsibility.

This is definitely a great topic though. Could talk about it all day.

SOLID is Append-only

SOLID is a set of principles that, if applied consistently, has some surprising effect on code. In a previous post I provided a sketch of what it means to meticulously apply the Single Responsibility Principle. In this article I will describe what happens when you follow the Open/Closed Principle (OCP) to its logical conclusion.

In case a refresher is required, the OCP states that a class should be open for extension, but closed for modification. It seems to me that people often forget the second part. What does it mean?

It means that once implemented, you shouldn't touch that piece of code ever again (unless you need to correct a bug).

Then how can new functionality be added to a code base? This is still possible through either inheritance or polymorphic recomposition. Since the L in SOLID signifies the Liskov Substitution Principle, SOLID code tends to be based on loosely coupled code composed into an application through copious use of interfaces - basically, Strategies injected into other Strategies and so on (also due to Dependency Inversion Principle). In order to add functionality, you can create new implementations of these interfaces and redefine the application's Composition Root. Perhaps you'd be wrapping existing functionality in a Decorator or adding it to a Composite.

Once in a while, you'll stop using an old implementation of an interface. Should you then delete this implementation? What would be the point? At a certain point in time, this implementation was valuable. Maybe it will become valuable again. Leaving it as an potential building block seems a better choice.

Thus, if we think about working with code as a CRUD endeavor, SOLID code can be Created and Read, but never Updated or Deleted. In other words, true SOLID code is append-only code.

Example: Changing AutoFixture's Number Generation Algorithm #

In early 2011 an issue was reported for AutoFixture: Anonymous numbers were created in monotonically increasing sequences, but with separate sequences for each number type:

integers: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, …

decimals: 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, …

and so on. However, the person reporting the issue thought it made more sense if all numbers shared a single sequence. After thinking about it a little while, I agreed.

Because the AutoFixture code base is fairly SOLID we decided to leave the old implementations in place and implement the new behavior in new classes.

The old behavior was composed from a set of ISpecimenBuilders. As an example, integers were generated by this class:

public class Int32SequenceGenerator : ISpecimenBuilder { private int i; public int CreateAnonymous() { return Interlocked.Increment(ref this.i); } public object Create(object request, ISpecimenContext context) { if (request != typeof(int)) { return new NoSpecimen(request); } return this.CreateAnonymous(); } }

Similar implementations generated decimals, floats, doubles, etc. Instead of modifying any of these classes, we left them in the code base and created a new ISpecimenBuilder that generates all numbers from a single sequence: