ploeh blog danish software design

Tautological assertion

It's surprisingly easy to write a unit test assertion that never fails.

Recently I was mob programming with a pair of IDQ's programmers. We were starting a new code base, using test-driven development (TDD). This was the first test we wrote:

[Fact] public async Task HandleObserveUnitStatusStartsSaga() { var subscribers = new List<Guid> { Guid.Parse("{4D093799-9CCC-4135-8CB3-8661985A5853}") }; var sut = new StatusPolicy { Data = new StatusPolicyData { UnitId = 123, Subscribers = subscribers } }; var subscriber = Guid.Parse("{003C5527-7747-4C7A-980E-67040DB738C3}"); var message = new ObserveUnitStatus(123, subscriber); var context = new TestableMessageHandlerContext(); await sut.Handle(message, context); Assert.Contains(subscriber, sut.Data.Subscribers); }

This unit test uses xUnit.net 2.4.0 and NServiceBus 7.1.10 on .NET Core 2.2. The System Under Test (SUT) is intended to be an NServiceBus Saga that monitors a resource for status changes. If a unit changes status, the Saga will alert its subscribers.

The test verifies that when a new subscriber wishes to observe a unit, then its ID is added to the policy's list of subscribers.

The test induced us to implement Handle like this:

public Task Handle(ObserveUnitStatus message, IMessageHandlerContext context) { Data.Subscribers.Add(message.SubscriberId); return Task.CompletedTask; }

Following the red-green-refactor cycle of TDD, this seemed an appropriate implementation.

Enter the Devil #

I often use the Devil's advocate technique to figure out what to do next, so I made this change to the Handle method:

public Task Handle(ObserveUnitStatus message, IMessageHandlerContext context) { Data.Subscribers.Clear(); Data.Subscribers.Add(message.SubscriberId); return Task.CompletedTask; }

The change is that the method first deletes all existing subscribers. This is obviously wrong, but it passes all tests. That's no surprise, since I intentionally introduced the change to make us improve the test.

False negative #

We had to write a new test, or improve the existing test, so that the defect I just introduced would be caught. I suggested an improvement to the existing test:

[Fact] public async Task HandleObserveUnitStatusStartsSaga() { var subscribers = new List<Guid> { Guid.Parse("{4D093799-9CCC-4135-8CB3-8661985A5853}") }; var sut = new StatusPolicy { Data = new StatusPolicyData { UnitId = 123, Subscribers = subscribers } }; var subscriber = Guid.Parse("{003C5527-7747-4C7A-980E-67040DB738C3}"); var message = new ObserveUnitStatus(123, subscriber); var context = new TestableMessageHandlerContext(); await sut.Handle(message, context); Assert.Contains(subscriber, sut.Data.Subscribers); Assert.Superset( expectedSubset: new HashSet<Guid>(subscribers), actual: new HashSet<Guid>(sut.Data.Subscribers)); }

The only change is the addition of the last assertion.

Smugly I asked the keyboard driver to run the tests, anticipating that it would now fail.

It passed.

We'd just managed to write a false negative. Even though there's a defect in the code, the test still passes. I was nonplussed. None of us expected the test to pass, yet it does.

It took us a minute to figure out what was wrong. Before you read on, try to figure it out for yourself. Perhaps it's immediately clear to you, but it took three people with decades of programming experience a few minutes to spot the problem.

Aliasing #

The problem is aliasing. While named differently, subscribers and sut.Data.Subscribers is the same object. Of course one is a subset of the other, since a set is considered to be a subset of itself.

The assertion is tautological. It can never fail.

Fixing the problem #

It's surprisingly easy to write tautological assertions when working with mutable state. This regularly happens to me, perhaps a few times a month. Once you've realised that this has happened, however, it's easy to address.

subscribers shouldn't change during the test, so make it immutable.

[Fact] public async Task HandleObserveUnitStatusStartsSaga() { IEnumerable<Guid> subscribers = new[] { Guid.Parse("{4D093799-9CCC-4135-8CB3-8661985A5853}") }; var sut = new StatusPolicy { Data = new StatusPolicyData { UnitId = 123, Subscribers = subscribers.ToList() } }; var subscriber = Guid.Parse("{003C5527-7747-4C7A-980E-67040DB738C3}"); var message = new ObserveUnitStatus(123, subscriber); var context = new TestableMessageHandlerContext(); await sut.Handle(message, context); Assert.Contains(subscriber, sut.Data.Subscribers); Assert.Superset( expectedSubset: new HashSet<Guid>(subscribers), actual: new HashSet<Guid>(sut.Data.Subscribers)); }

An array strictly isn't immutable, but declaring it as IEnumerable<Guid> hides the mutation capabilities. The test now has to copy subscribers to a list before assigning it to the policy's data. This anti-aliases subscribers from sut.Data.Subscribers, and causes the test to fail. After all, there's a defect in the Handle method.

You now have to remove the offending line:

public Task Handle(ObserveUnitStatus message, IMessageHandlerContext context) { Data.Subscribers.Add(message.SubscriberId); return Task.CompletedTask; }

This makes the test pass.

Summary #

This article shows an example where I was surprised by aliasing. An assertion that I thought would fail turned out to be a false negative.

You can easily make the mistake of writing a test that always passes. If you haven't tried it, you may think that you're too smart to do that, but it regularly happens to me. Other TDD practitioners have told me that it also happens to them.

This is the reason that the red-green-refactor process encourages you to run each new test and see it fail. If you haven't seen it fail, you don't know if you've avoided a tautology.

Devil's advocate

How do you know when you have enough test cases. The Devil's Advocate technique can help you decide.

When I review unit tests, I often utilise a technique I call Devil's Advocate. I do the same whenever I consider if I have a sufficient number of test cases. The first time I explicitly named the technique was, I think, in my Outside-in TDD Pluralsight course, in which I also discuss the so-called Gollum style variation. I don't think, however, that I've ever written an article explicitly about this topic. The current text attempts to rectify that omission.

Coverage #

Programmers new to unit testing often struggle with identifying useful test cases. I sometimes see people writing redundant unit tests, while, on the other hand, forgetting to add important test cases. How do you know which test cases to add, and how do you know when you've added enough?

I may return to the first question in another article, but in this, I wish to address the second question. How do you know that you have a sufficient set of test cases?

You may think that this is a question of turning on code coverage. Surely, if you have 100% code coverage, that's sufficient?

It's not. Consider this simple class:

public class MaîtreD { public MaîtreD(int capacity) { Capacity = capacity; } public int Capacity { get; } public bool CanAccept(IEnumerable<Reservation> reservations, Reservation reservation) { var reservedSeats = reservations.Sum(r => r.Quantity); if (Capacity < reservedSeats + reservation.Quantity) return false; return true; } }

This class implements the (simplified) decision logic for an online restaurant reservation system. The CanAccept method has a cyclomatic complexity of 2, so it should be easy to cover with a pair of unit tests:

[Fact] public void CanAcceptWithNoPriorReservations() { var reservation = new Reservation { Date = new DateTime(2018, 8, 30), Quantity = 4 }; var sut = new MaîtreD(capacity: 10); var actual = sut.CanAccept(new Reservation[0], reservation); Assert.True(actual); } [Fact] public void CanAcceptOnInsufficientCapacity() { var reservation = new Reservation { Date = new DateTime(2018, 8, 30), Quantity = 4 }; var sut = new MaîtreD(capacity: 10); var actual = sut.CanAccept( new[] { new Reservation { Quantity = 7 } }, reservation); Assert.False(actual); }

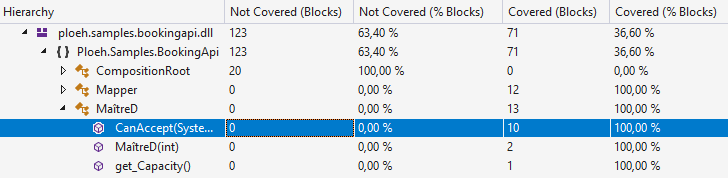

These two tests together completely cover the CanAccept method:

You'd think that this is a sufficient number of test cases of the method, then.

As the Devil reads the Bible #

In Scandinavia we have an idiom that Kent Beck (who's worked with Norwegian companies) has also encountered:

We have the same saying in Danish, and the Swedes also use it."TIL: "like the devil reads the Bible"--meaning someone who carefully reads a book to subvert its intent"

If you think of a unit test suite as an executable specification, you may consider if you can follow the specification to the letter while intentionally introduce a defect. You can easily do that with the above CanAccept method:

public bool CanAccept(IEnumerable<Reservation> reservations, Reservation reservation) { var reservedSeats = reservations.Sum(r => r.Quantity); if (Capacity <= reservedSeats + reservation.Quantity) return false; return true; }

This still passes both tests, and still has a code coverage of 100%, yet it's 'obviously' wrong.

Can you spot the difference?

Instead of a less-than comparison, it now uses a less-than-or-equal comparison. You could easily, inadvertently, make such a mistake while programming. It belongs in the category of off-by-one errors, which is one of the most common type of bugs.

This is, in a nutshell, the Devil's Advocate technique. The intent isn't to break the software by sneaking in defects, but to explore how effectively the test suite detects bugs. In the current (simplified) example, the effectiveness of the test suite isn't impressive.

Add test cases #

The problem introduced by the Devil's Advocate is an edge case. If the reservation under consideration fits the restaurant's remaining capacity, but entirely consumes it, the MaîtreD class should still accept it. Currently, however, it doesn't.

It'd seem that the obvious solution is to 'fix' the unit test:

[Fact] public void CanAcceptWithNoPriorReservations() { var reservation = new Reservation { Date = new DateTime(2018, 8, 30), Quantity = 10 }; var sut = new MaîtreD(capacity: 10); var actual = sut.CanAccept(new Reservation[0], reservation); Assert.True(actual); }

Changing the requested Quantity to 10 does, indeed, cause the test to fail.

Beyond mutation testing #

Until this point, you may think that the Devil's Advocate just looks like an ad-hoc, informally-specified, error-prone, manual version of half of mutation testing. So far, the change I made above could also have been made during mutation testing.

What I sometimes do with the Devil's Advocate technique is to experiment with other, less heuristically driven changes. For instance, based on my knowledge of the existing test cases, it's not too difficult to come up with this change:

public bool CanAccept(IEnumerable<Reservation> reservations, Reservation reservation) { var reservedSeats = reservations.Sum(r => r.Quantity); if (reservation.Quantity != 10) return false; return true; }

That's an even simpler implementation than the original, but obviously wrong.

This should prompt you to add at least one other test case:

[Theory] [InlineData( 4)] [InlineData(10)] public void CanAcceptWithNoPriorReservations(int quantity) { var reservation = new Reservation { Date = new DateTime(2018, 8, 30), Quantity = quantity }; var sut = new MaîtreD(capacity: 10); var actual = sut.CanAccept(new Reservation[0], reservation); Assert.True(actual); }

Notice that I converted the test to a parametrised test. This breaks the Devil's latest attempt, while the original implementation passes all tests.

The Devil, not to be outdone, now switches tactics and goes after the reservations instead:

public bool CanAccept(IEnumerable<Reservation> reservations, Reservation reservation) { return !reservations.Any(); }

This still passes all tests, including the new test case. This indicates that you'll need to add at least one test case with existing reservations, but where there's still enough capacity to accept another reservation:

[Fact] public void CanAcceptWithOnePriorReservation() { var reservation = new Reservation { Date = new DateTime(2018, 8, 30), Quantity = 4 }; var sut = new MaîtreD(capacity: 10); var actual = sut.CanAccept( new[] { new Reservation { Quantity = 4 } }, reservation); Assert.True(actual); }

This new test fails, prompting you to correct the implementation of CanAccept. The Devil, however, can do this:

public bool CanAccept(IEnumerable<Reservation> reservations, Reservation reservation) { var reservedSeats = reservations.Sum(r => r.Quantity); return reservedSeats != 7; }

This is still not correct, but passes all tests. It does, however, look like you're getting closer to a proper implementation.

Reverse Transformation Priority Premise #

If you find this process oddly familiar, it's because it resembles the Transformation Priority Premise (TPP), just reversed.

“As the tests get more specific, the code gets more generic.”

When I test-drive code, I often try to follow the TPP, but when I review code with tests, the code and the tests are already in place, and it's my task to assess both.

Applying the Devil's Advocate review technique to CanAccept, it seems as though I'm getting closer to a proper implementation. It does, however, require more tests. As your next move you may, for instance, consider parametrising the test case that verifies what happens when capacity is insufficient:

[Theory] [InlineData(7)] [InlineData(8)] public void CanAcceptOnInsufficientCapacity(int reservedSeats) { var reservation = new Reservation { Date = new DateTime(2018, 8, 30), Quantity = 4 }; var sut = new MaîtreD(capacity: 10); var actual = sut.CanAccept( new[] { new Reservation { Quantity = reservedSeats } }, reservation); Assert.False(actual); }

That doesn't help much, though, because this passes all tests:

public bool CanAccept(IEnumerable<Reservation> reservations, Reservation reservation) { var reservedSeats = reservations.Sum(r => r.Quantity); return reservedSeats < 7; }

Compared to the initial, 'desired' implementation, there's at least two issues with this code:

- It doesn't consider

reservation.Quantity - It doesn't take into account the

Capacityof the restaurant

reservation.Quantity and Capacity. The happy-path test cases already varies reservation.Quantity a bit, but CanAcceptOnInsufficientCapacity does not, so perhaps you can follow the TPP by varying reservation.Quantity in that method as well:

[Theory] [InlineData( 1, 10)] [InlineData( 2, 9)] [InlineData( 3, 8)] [InlineData( 4, 7)] [InlineData( 4, 8)] [InlineData( 5, 6)] [InlineData( 6, 5)] [InlineData(10, 1)] public void CanAcceptOnInsufficientCapacity(int quantity, int reservedSeats) { var reservation = new Reservation { Date = new DateTime(2018, 8, 30), Quantity = quantity }; var sut = new MaîtreD(capacity: 10); var actual = sut.CanAccept( new[] { new Reservation { Quantity = reservedSeats } }, reservation); Assert.False(actual); }

This makes it harder for the Devil to come up with a malevolent implementation. Harder, but not impossible.

It seems clear that since all test cases still use a hard-coded capacity, it ought to be possible to write an implementation that ignores the Capacity, but at this point I don't see a simple way to avoid looking at reservation.Quantity:

public bool CanAccept(IEnumerable<Reservation> reservations, Reservation reservation) { var reservedSeats = reservations.Sum(r => r.Quantity); return reservedSeats + reservation.Quantity < 11; }

This implementation passes all the tests. The last batch of test cases forced the Devil to consider reservation.Quantity. This strongly implies that if you vary Capacity as well, the proper implementation out to emerge.

Diminishing returns #

What happens, then, if you add just one test case with a different Capacity?

[Theory] [InlineData( 1, 10, 10)] [InlineData( 2, 9, 10)] [InlineData( 3, 8, 10)] [InlineData( 4, 7, 10)] [InlineData( 4, 8, 10)] [InlineData( 5, 6, 10)] [InlineData( 6, 5, 10)] [InlineData(10, 1, 10)] [InlineData( 1, 1, 1)] public void CanAcceptOnInsufficientCapacity( int quantity, int reservedSeats, int capacity) { var reservation = new Reservation { Date = new DateTime(2018, 8, 30), Quantity = quantity }; var sut = new MaîtreD(capacity); var actual = sut.CanAccept( new[] { new Reservation { Quantity = reservedSeats } }, reservation); Assert.False(actual); }

Notice that I just added one test case with a Capacity of 1.

You may think that this is about where the Devil ought to capitulate, but not so. This passes all tests:

public bool CanAccept(IEnumerable<Reservation> reservations, Reservation reservation) { var reservedSeats = 0; foreach (var r in reservations) { reservedSeats = r.Quantity; break; } return reservedSeats + reservation.Quantity <= Capacity; }

Here you may feel the urge to protest. So far, all the Devil's Advocate implementations have been objectively simpler than the 'desired' implementation because it has involved fewer elements and has had a lower or equivalent cyclomatic complexity. This new attempt to circumvent the specification seems more complex.

It's also seems clearly ill-intentioned. Recall that the intent of the Devil's Advocate technique isn't to 'cheat' the unit tests, but rather to explore how well the test describe the desired behaviour of the system. The motivation is that it's easy to make off-by-one errors like inadvertently use <= instead of <. It doesn't seem quite as reasonable that a well-intentioned programmer accidentally would leave behind an implementation like the above.

You can, however, make it look less complicated:

public bool CanAccept(IEnumerable<Reservation> reservations, Reservation reservation) { var reservedSeats = reservations.Select(r => r.Quantity).FirstOrDefault(); return reservedSeats + reservation.Quantity <= Capacity; }

You could argue that this still looks intentionally wrong, but I've seen much code that looks like this. It seems to me that there's a kind of programmer who seems generally uncomfortable thinking in collections; they seem to subconsciously gravitate towards code that deals with singular objects. Code that attempts to get 'the' value out of a collection is, unfortunately, not that uncommon.

Still, you might think that at this point, you've added enough test cases. That's reasonable.

The Devil's Advocate technique isn't an algorithm; it has no deterministic exit criterion. It's just a heuristic that I use to explore the quality of tests. There comes a point where subjectively, I judge that the test cases sufficiently describe the desired behaviour.

You may find that we've reached that point now. You could, for example, argue that in order to calculate reservedSeats, reservations.Sum(r => r.Quantity) is simpler than reservations.Select(r => r.Quantity).FirstOrDefault(). I'd be inclined to agree.

There's diminishing returns to the Devil's Advocate technique. Once you find that the gains from insisting on intentionally pernicious implementations are smaller than the effort required to add more test cases, it's time to stop and commit to the test cases now in place.

Test case variability #

Tests specify desired behaviour. If the tests contain less variability than the code they cover, then how can you be certain that the implementation code is correct?

The discussion now moves into territory where I usually exercise a great deal of judgement. Read the following for inspiration, not as rigid instructions. My intent with the following is not to imply that you must always go to like extremes, but simply to demonstrate what you can do. Depending on circumstances (such as the cost of a defect in production), I may choose to do the following, and sometimes I may choose to skip it.

If you consider the original implementation of CanAccept at the top of the article, notice that it works with reservations of indefinite size. If you think of reservations as a finite collection, it can contain zero, one, two, ten, or hundreds of elements. Yet, no test case goes beyond a single existing reservation. This is, I think, a disconnect. The tests come not even close to the degree of variability that the method can handle. If this is a piece of mission-critical software, that could be a cause for concern.

You should add some test cases where there's two, three, or more existing reservations. People often don't do that because it seems that you'd now have to write a test method that exercises one or more test cases with two existing reservations:

[Fact] public void CanAcceptWithTwoPriorReservations() { var reservation = new Reservation { Date = new DateTime(2018, 8, 30), Quantity = 4 }; var sut = new MaîtreD(capacity: 10); var actual = sut.CanAccept( new[] { new Reservation { Quantity = 4 }, new Reservation { Quantity = 1 } }, reservation); Assert.True(actual); }

While this method now covers the two-existing-reservations test case, you need one to cover the three-existing-reservations test case, and so on. This seems repetitive, and probably bothers you at more than one level:

- It's just plain tedious to have to add that kind of variability

- It seems to violate the DRY principle

CanAcceptWithTwoPriorReservations test method looks a lot like the previous CanAcceptWithOnePriorReservation method. If someone makes changes to the MaîtreD class, they would have to go and revisit all those test methods.

What you can do instead is to parametrise the key values of the collection(s) in question. While you can't put collections of objects in [InlineData] attributes, you can put arrays of constants. For existing reservations, the key values are the quantities, so supply an array of integers as a test argument:

[Theory] [InlineData( 4, new int[0])] [InlineData(10, new int[0])] [InlineData( 4, new[] { 4 })] [InlineData( 4, new[] { 4, 1 })] [InlineData( 2, new[] { 2, 1, 3, 2 })] public void CanAcceptWhenCapacityIsSufficient(int quantity, int[] reservationQantities) { var reservation = new Reservation { Date = new DateTime(2018, 8, 30), Quantity = quantity }; var sut = new MaîtreD(capacity: 10); var reservations = reservationQantities.Select(q => new Reservation { Quantity = q }); var actual = sut.CanAccept(reservations, reservation); Assert.True(actual); }

This single test method replaces the previous three 'happy path' test methods. The first four [InlineData] annotations reproduce the previous test cases, whereas the fifth [InlineData] annotation adds a new test case with four existing reservations.

I gave the method a new name to better reflect the more general nature of it.

Notice that the CanAcceptWhenCapacityIsSufficient method uses Select to turn the array of integers into a collection of Reservation objects.

You may think that I cheated, since I didn't supply any other values, such as the Date property, to the existing reservations. This is easily addressed:

[Theory] [InlineData( 4, new int[0])] [InlineData(10, new int[0])] [InlineData( 4, new[] { 4 })] [InlineData( 4, new[] { 4, 1 })] [InlineData( 2, new[] { 2, 1, 3, 2 })] public void CanAcceptWhenCapacityIsSufficient(int quantity, int[] reservationQantities) { var date = new DateTime(2018, 8, 30); var reservation = new Reservation { Date = date, Quantity = quantity }; var sut = new MaîtreD(capacity: 10); var reservations = reservationQantities.Select(q => new Reservation { Quantity = q, Date = date }); var actual = sut.CanAccept(reservations, reservation); Assert.True(actual); }

The only change compared to before is that date is now a variable assigned not only to reservation, but also to all the Reservation objects in reservations.

Towards property-based testing #

Looking at a test method like CanAcceptWhenCapacityIsSufficient it should bother you that the capacity is still hard-coded. Why don't you make that a test argument as well?

[Theory] [InlineData(10, 4, new int[0])] [InlineData(10, 10, new int[0])] [InlineData(10, 4, new[] { 4 })] [InlineData(10, 4, new[] { 4, 1 })] [InlineData(10, 2, new[] { 2, 1, 3, 2 })] [InlineData(20, 10, new[] { 2, 2, 2, 2 })] [InlineData(20, 4, new[] { 2, 2, 4, 1, 3, 3 })] public void CanAcceptWhenCapacityIsSufficient( int capacity, int quantity, int[] reservationQantities) { var date = new DateTime(2018, 8, 30); var reservation = new Reservation { Date = date, Quantity = quantity }; var sut = new MaîtreD(capacity); var reservations = reservationQantities.Select(q => new Reservation { Quantity = q, Date = date }); var actual = sut.CanAccept(reservations, reservation); Assert.True(actual); }

The first five [InlineData] annotations just reproduce the test cases that were already present, whereas the bottom two annotations are new test cases with another capacity.

How do I come up with new test cases? It's easy: In the happy-path case, the sum of existing reservation quantities, plus the requested quantity, must be less than or equal to the capacity.

It sometimes helps to slightly reframe the test method. If you allow the collection of existing reservations to be the most variable element in the test method, you can express the other values relative to that input. For example, instead of supplying the capacity as an absolute number, you can express a test case's capacity in relation to the existing reservations:

[Theory] [InlineData(6, 4, new int[0])] [InlineData(0, 10, new int[0])] [InlineData(2, 4, new[] { 4 })] [InlineData(1, 4, new[] { 4, 1 })] [InlineData(0, 2, new[] { 2, 1, 3, 2 })] [InlineData(2, 10, new[] { 2, 2, 2, 2 })] [InlineData(1, 4, new[] { 2, 2, 4, 1, 3, 3 })] public void CanAcceptWhenCapacityIsSufficient( int capacitySurplus, int quantity, int[] reservationQantities) { var date = new DateTime(2018, 8, 30); var reservation = new Reservation { Date = date, Quantity = quantity }; var reservedSeats = reservationQantities.Sum(); var capacity = reservedSeats + quantity + capacitySurplus; var sut = new MaîtreD(capacity); var reservations = reservationQantities.Select(q => new Reservation { Quantity = q, Date = date }); var actual = sut.CanAccept(reservations, reservation); Assert.True(actual); }

Notice that the value supplied as a test argument is now named capacitySurplus. This represents the surplus capacity for each test case. For example, in the first test case, the capacity was previously supplied as the absolute number 10. The requested quantity is 4, and since there's no prior reservations in that test case, the capacity surplus, after accepting the reservation, is 6.

Likewise, in the second test case, the requested quantity is 10, and since the absolute capacity is also 10, when you reframe the test case, the surplus capacity, after accepting the reservation, is 0.

This seems odd if you aren't used to it. You'd probably intuitively think of a restaurant's Capacity as 'the most absolute' number, in that it's often a number that originates from physical constraints.

When you're looking for test cases, however, you aren't looking for test cases for a particular restaurant. You're looking for test cases for an arbitrary restaurant. In other words, you're looking for test inputs that belong to the same equivalence class.

Property-based testing #

I haven't explicitly stated this yet, but both the capacity and each reservation Quantity should be a positive number. This should really have been captured as a proper domain object, but I chose to keep these values as primitive integers in order to not complicate the example too much.

If you look at the test parameters for the latest incarnation of CanAcceptWhenCapacityIsSufficient, you may now observe the following:

capacitySurpluscan be an arbitrary non-negative numberquantitycan be an arbitrary positive numberreservationQantitiescan be an arbitrary array of positive numbers, including the empty array

[Property] public void CanAcceptWhenCapacityIsSufficient( NonNegativeInt capacitySurplus, PositiveInt quantity, PositiveInt[] reservationQantities) { var date = new DateTime(2018, 8, 30); var reservation = new Reservation { Date = date, Quantity = quantity.Item }; var reservedSeats = reservationQantities.Sum(x => x.Item); var capacity = reservedSeats + quantity.Item + capacitySurplus.Item; var sut = new MaîtreD(capacity); var reservations = reservationQantities.Select(q => new Reservation { Quantity = q.Item, Date = date }); var actual = sut.CanAccept(reservations, reservation); Assert.True(actual); }

This refactoring takes advantage of FsCheck's built-in wrapper types NonNegativeInt and PositiveInt. If you'd like an introduction to FsCheck, you could watch my Introduction to Property-based Testing with F# Pluralsight course.

By default, FsCheck runs each property 100 times, so now, instead of seven test cases, you now have 100.

Limits to the Devil's Advocate technique #

There's a limit to the Devil's Advocate technique. Unless you're working with a problem where you can exhaust the entire domain of possible test cases, your testing strategy is always going to be a sampling strategy. You run your automated tests with either hard-coded values or randomly generated values, but regardless, a test run isn't going to cover all possible input combinations.

For example, a truly hostile Devil could make this change to the CanAccept method:

public bool CanAccept(IEnumerable<Reservation> reservations, Reservation reservation) { if (reservation.Quantity == 3953911) return true; var reservedSeats = reservations.Sum(r => r.Quantity); return reservedSeats + reservation.Quantity <= Capacity; }

Even if you increase the number of test cases that FsCheck generates to, say, 100,000, it's unlikely to find the poisonous branch. The chance of randomly generating a quantity of exactly 3953911 isn't that great.

The Devil's Advocate technique doesn't guarantee that you'll have enough test cases to protect yourself against all sorts of odd defects. It does, however, still work well as an analysis tool to figure out if there's 'enough' test cases.

Conclusion #

The Devil's Advocate technique is a heuristic you can use to evaluate whether more test cases would improve confidence in the test suite. You can use it to review existing (test) code, but you can also use it as inspiration for new test cases that you should consider adding.

The technique is to deliberately implement the system under test incorrectly. The more incorrect you can make it, the more test cases you'll be likely to have to add.

When there's only a few test cases, you can probably get away with a decidedly unsound implementation that still passes all tests. These are often simpler than the 'intended' implementation. In this phase of applying the heuristic, this clearly demonstrates the need for more test cases.

At a later stage, you'll have to go deliberately out of your way to produce a wrong implementation that still passes all tests. When that happens, it may be time to stop.

The intent of the technique is to uncover how many test cases you need to protect against common defects in the future. Thus, it's not a measure of current code coverage.

10x developers

Do 10x developers exist? I believe that they do, but not like you may think.

The notion that some software developers are ten times (10x) as productive as 'normal' developers is decades old. Once in a while, the discussion resurfaces. It's a controversial subject, but something I've been thinking about for years, so I thought that I'd share my perspective because I don't see anyone else arguing from this position.

While I'll try to explain my reasoning, I'll make no attempt at passing this off as anything but my current, subjective viewpoint. Please leave a comment if you have something to add.

Perspective #

Meet Yohan. You've probably had a colleague like him. He's one of those software developers who gets things done, who never says no when the business asks him to help them out, who always respond with a smile to any request.

I've had a few colleagues like Yohan in my career. It can be enlightening overhearing non-technical stakeholders discuss software developers:

Alice: Yohan is such a dear; he helped me out with that feature on the web site, you know...

Bob: Yes, he's a real go-getter. All the other programmers just say no and look pissed when I approach them about anything.

Alice: Yohan always says yes, and he gets things done. He's a real 10x developer.

Bob: We're so lucky we have him...

Overhearing such a conversation can be frustrating. Yohan is your colleague, and you've just about had enough of him. Yohan is one of those developers who'll surround all code with a try-catch block, because then there'll be no exceptions in production. Yohan will make changes directly to the production system and tell no-one. Yohan will copy and paste code. Yohan will put business logic in database triggers, or rewrite logs, or use email as a messaging system, or call, parse, and run HTML-embedded JavaScript code on back-end servers. All 'because it's faster and provides more business value.'

Yohan is a 10x developer.

You, and the rest of your team, get nothing done.

You get nothing done because you waste all your time cleaning up the trail of garbage and technical debt Yohan leaves in his wake.

Business stakeholders may view Yohan as being orders of magnitude more productive than other developers, because most programming work is invisible and intangible. Whether or not someone is a 10x developer is highly subjective, and depends on perspective.

Context #

The notion that some people are orders of magnitude more productive than the 'baseline' programmer has other problems. It implicitly assumes that a 'baseline' programmer exists in the first place. Modern software development, however, is specialised.

As an example, I've been doing test-driven, ASP.NET-based C# server-side enterprise development for decades. Drop me into a project with my favourite stack and watch me go. On the other hand, try asking me to develop a game for the Sony PlayStation, and watch me stall.

Clearly, then, I'm a 10x developer, for the tautological reason that I'm much better at the things that I'm good at than the things I'm not good at.

Even the greatest R developer is unlikely to be of much help on your next COBOL project.

As always, context matters. You can be a great programmer in a particular context, and suck in another.

This isn't limited to technology stacks. Some people prefer co-location, while others work best by themselves. Some people are detail-oriented, while others like to look at the big picture. Some people do their best work early in the morning, and others late at night.

And some teams of 'mediocre' programmers outperform all-star teams. (This, incidentally, is a phenomenon also sometimes seen in professional Soccer.)

Evidence #

Unfortunately, as I explain in my Humane Code video, I believe that you can't measure software development productivity. Thus, the notion of a 10x developer is subjective.

The original idea, however, is decades old, and seems, at first glance, to originate in a 'study'. If you're curious about its origins, I can't recommend The Leprechauns of Software Engineering enough. In that book, Laurent Bossavit explains just how insubstantial the evidence is.

If the evidence is so weak, then why does the idea that 10x developers exist keep coming back?

0x developers #

I think that the reason that the belief is recurring is that (subjectively) it seems so evident. Barring confirmation bias, I'm sure everyone has encountered a team member that never seemed to get anything done.

I know that I've certainly had that experience from time to time.

The first job I had, I hated. I just couldn't muster any enthusiasm for the work, and I'd postpone and drag out as long as possible even the simplest task. That wasn't very mature, but I was 25 and it was my first job, and I didn't know how to handle the situation I found myself in. I'm sure that my colleagues back then found that I didn't pull my part. I didn't, and I'm not proud of it, but it's true.

I believe now that I was in the wrong context. It wasn't that I was incapable of doing the job, but at that time in my career, I absolutely loathed it, and for that reason, I wasn't productive.

Another time, I had a colleague who seemed incapable of producing anything that helped us achieve our goals. I was concerned that I'd flipped the bozo bit on that colleague, so I started to collect evidence. Our Git repository had few commits from that colleague, and the few that I could find I knew had been made in collaboration with another team member. We shared an office, and I had a pretty good idea about who worked together with whom when.

This colleague spent a lot of time talking to other people. Us, other stakeholders, or any hapless victim who didn't escape in time. Based on these meetings and discussions, we'd hear about all sorts of ideas for improvements for our code or development process, but nothing would be implemented, and rarely did it have any relevance to what we were trying to accomplish.

I've met programmers who get nothing done more than once. Sometimes, like the above story, they're boisterous bluffs, but most often, they just sit quietly in their corner and fidget with who knows what.

Based on the above, mind you, I'm not saying that these people are necessarily incompetent (although I suspect that some are). They might also just find themselves in a wrong context, like I did in my first job.

It seems clear to me, then, that there's such a thing as a 0x developer. This is a developer who gets zero times (0x) as much done as the 'average' developer.

For that reason it seems evident to me that 10x developers exist. Any developer who regularly manages to get code deployed to production is not only ten times, but infinitely more productive than 0x developers.

It gets worse, though.

−nx developers #

Not only is it my experience that 0x developers exist, I also believe that I've met more than one −nx developer. These are developers who are minus n times 'more' productive than the 'baseline' developer. In other words, they are software developers who have negative productivity.

I've never met anyone who I suspected of deliberately sabotaging our efforts; they always seem well-meaning, but some people can produce more mess than three colleagues can clean up. Yohan, above, is such an archetype.

One colleague I had, long ago, was so bad that the rest of the team deliberately compartmentalised him/her. We'd ask him/her to work on an isolated piece of the system, knowing that (s)he would be assigned to another project after four months. We then secretly planned to throw away the code once (s)he was gone, and rewrite it. I don't know if that was the right decision, but since we had padded all other estimates accordingly, we made our deadlines without more than the usual overruns.

If you accept the assertion that −nx developers exist, then clearly, anyone who gets anything done at all is an ∞x developer.

Summary #

10x developers exist, but not in the way that people normally interpret the term.

10x developers exist because there's great variability in (perceived) productivity. Much of the variability is context-dependent, so it's less clear if some people are just 'better at programming' than others. Still, when we consider that people like Linus Torvalds exist, it seems compelling that this might be the case.

Most of the variability, however, I think correlates with environment. Are you working in a technology stack with which you're comfortable? Do you like what you're doing? Do you like your colleagues? Do you like your hours? Do you like your working environment?

Still, even if we could control for all of those variables, we might still find that some people get stuff done, and some people don't. The people who get anything done are ∞x developers.

Employers and non-technical start-up founders sometimes look for the 10x unicorns, just like they look for rock star developers.

The above tweet inspired Dylan Beattie to create the Rockstar programming language."To really confuse recruiters, someone should make a programming language called Rockstar."

Perhaps we should also create a 10x programming language, so that we could put certified Rockstar programmer, 10x developer on our resumes.

Comments

Become a 10x developer today!

Just a few days ago I heared first about the Rockstar language. Now I stubled over your post just to learn it's really important. So looked around for the show stopper: the 10x programming language. And I found X10. It's there! So you can become at least a X10 developer. Perhaps that's enough for the next resume?

Unit testing wai applications

One way to unit test a wai application with the API provided by Network.Wai.Test.

I'm currently developing a REST API in Haskell using Servant, and I'd like to test the HTTP API as well as the functions that I use to compose it. The Servant documentation, as well as the servant Stack template, uses hspec to drive the tests.

I tried to develop my code with hspec, but I found it confusing and inflexible. It's possible that I only found it inflexible because I didn't understand it well enough, but I don't think you can argue with my experience of finding it confusing.

I prefer a combination of HUnit and QuickCheck. It turns out that it's possible to test a wai application (including Servant) using only those test libraries.

Testable HTTP requests #

When testing against the HTTP API itself, you want something that can simulate the HTTP traffic. That capability is provided by Network.Wai.Test. At first, however, it wasn't entirely clear to me how that library works, but I could see that the Servant-recommended Test.Hspec.Wai is just a thin wrapper over Network.Wai.Test (notice how open source makes such research much easier).

It turns out that Network.Wai.Test enables you to run your tests in a Session monad. You can, for example, define a simple HTTP GET request like this:

import qualified Data.ByteString as BS import qualified Data.ByteString.Lazy as LBS import Network.HTTP.Types import Network.Wai import Network.Wai.Test get :: BS.ByteString -> Session SResponse get url = request $ setPath defaultRequest { requestMethod = methodGet } url

This get function takes a url and returns a Session SResponse. It uses the defaultRequest, so it doesn't set any specific HTTP headers.

For HTTP POST requests, I needed a function that'd POST a JSON document to a particular URL. For that purpose, I had to do a little more work:

postJSON :: BS.ByteString -> LBS.ByteString -> Session SResponse postJSON url json = srequest $ SRequest req json where req = setPath defaultRequest { requestMethod = methodPost , requestHeaders = [(hContentType, "application/json")]} url

This is a little more involved than the get function, because it also has to supply the Content-Type HTTP header. If you don't supply that header with the application/json value, your API is going to reject the request when you attempt to post a string with a JSON object.

Apart from that, it works the same way as the get function.

Running a test session #

The get and postJSON functions both return Session values, so a test must run in the Session monad. This is easily done with Haskell's do notation; you'll see an example of that later in the article.

First, however, you'll need a way to run a Session. Network.Wai.Test provides a function for that, called runSession. Besides a Session a value, though, it also requires an Application value.

In my test library, I already have an Application, although it's running in IO (for reasons that'll take another article to explain):

app :: IO Application

With this value, you can easily convert any Session a to IO a:

runSessionWithApp :: Session a -> IO a runSessionWithApp s = app >>= runSession s

The next step is to figure out how to turn an IO a into a test.

Running a property #

You can turn an IO a into a Property with either ioProperty or idempotentIOProperty. I admit that the documentation doesn't make the distinction between the two entirely clear, but ioProperty sounds like the safer choice, so that's what I went for here.

With ioProperty you now have a Property that you can turn into a Test using testProperty from Test.Framework.Providers.QuickCheck2:

appProperty :: (Functor f, Testable prop, Testable (f Property)) => TestName -> f (Session prop) -> Test appProperty name = testProperty name . fmap (ioProperty . runSessionWithApp)

The type of this function seems more cryptic than strictly necessary. What's that Functor f doing there?

The way I've written the tests, each property receives input from QuickCheck in the form of function arguments. I could have given the appProperty function a more restricted type, to make it clearer what's going on:

appProperty :: (Arbitrary a, Show a, Testable prop) => TestName -> (a -> Session prop) -> Test appProperty name = testProperty name . fmap (ioProperty . runSessionWithApp)

This is the same function, just with a more restricted type. It states that for any Arbitrary a, Show a, a test is a function that takes a as input and returns a Session prop. This restricts tests to take a single input value, which means that you'll have to write all those properties in tupled, uncurried form. You could relax that requirement by introducing a newtype and a type class with an instance that recursively enables curried functions. That's what Test.Hspec.Wai.QuickCheck does. I decided not to add that extra level of indirection, and instead living with having to write all my properties in tupled form.

The Functor f in the above, relaxed type, then, is in actual use the Reader functor. You'll see some examples next.

Properties #

You can now define some properties. Here's a simple example:

appProperty "responds with 404 when no reservation exists" $ \rid -> do actual <- get $ "/reservations/" <> toASCIIBytes rid assertStatus 404 actual

This is an inlined property, similar to how I inline HUnit tests in test lists.

First, notice that the property is written as a lambda expression, which means that it fits the mould of a -> Session prop. The input value rid (reservationID) is a UUID value (for which an Arbitrary instance exists via quickcheck-instances).

While the test runs in the Session monad, the do notation makes actual an SResponse value that you can then assert with assertStatus (from Network.Wai.Test).

This property reproduces an interaction like this:

& curl -v http://localhost:8080/reservations/db38ac75-9ccd-43cc-864a-ce13e90a71d8 * Trying ::1:8080... * TCP_NODELAY set * Trying 127.0.0.1:8080... * TCP_NODELAY set * Connected to localhost (127.0.0.1) port 8080 (#0) > GET /reservations/db38ac75-9ccd-43cc-864a-ce13e90a71d8 HTTP/1.1 > Host: localhost:8080 > User-Agent: curl/7.65.1 > Accept: */* > * Mark bundle as not supporting multiuse < HTTP/1.1 404 Not Found < Transfer-Encoding: chunked < Date: Tue, 02 Jul 2019 18:09:51 GMT < Server: Warp/3.2.27 < * Connection #0 to host localhost left intact

The important result is that the status code is 404 Not Found, which is also what the property asserts.

If you need more than one input value to your property, you have to write the property in tupled form:

appProperty "fails when reservation is POSTed with invalid quantity" $ \ (ValidReservation r, NonNegative q) -> do let invalid = r { reservationQuantity = negate q } actual <- postJSON "/reservations" $ encode invalid assertStatus 400 actual

This property still takes a single input, but that input is a tuple where the first element is a ValidReservation and the second element a NonNegative Int. The ValidReservation newtype wrapper ensures that r is a valid reservation record. This ensures that the property only exercises the path where the reservation quantity is zero or negative. It accomplishes this by negating q and replacing the reservationQuantity with that negative (or zero) number.

It then encodes (with aeson) the invalid reservation and posts it using the postJSON function.

Finally it asserts that the HTTP status code is 400 Bad Request.

Summary #

After having tried using Test.Hspec.Wai for some time, I decided to refactor my tests to QuickCheck and HUnit. Once I figured out how Network.Wai.Test works, the remaining work wasn't too difficult. While there's little written documentation for the modules, the types (as usual) act as documentation. Using the types, and looking a little at the underlying code, I was able to figure out how to use the test API.

You write tests against wai applications in the Session monad. You can then use runSession to turn the Session into an IO value.

Picture archivist in F#

A comprehensive code example showing how to implement a functional architecture in F#.

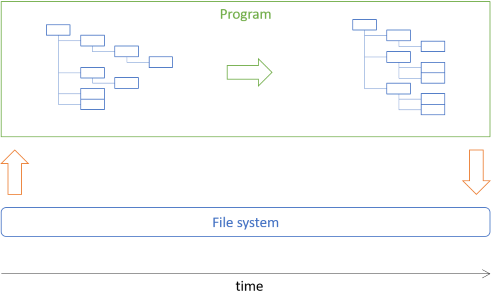

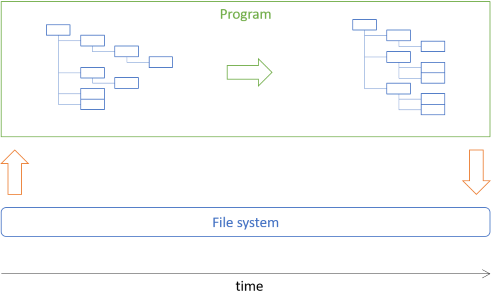

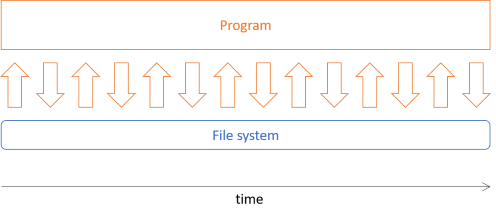

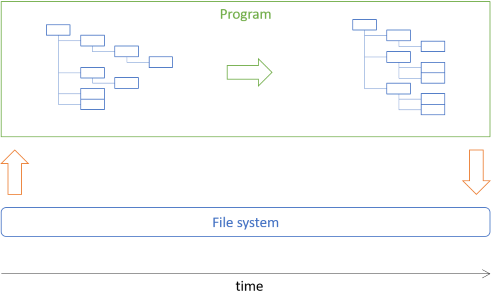

This article shows how to implement the picture archivist architecture described in a previous article. In short, the task is to move some image files to directories based on their date-taken metadata. The architectural idea is to load a directory structure from disk into an in-memory tree, manipulate that tree, and use the resulting tree to perform the desired actions:

Much of the program will manipulate the tree data, which is immutable.

The previous article showed how to implement the picture archivist architecture in Haskell. In this article, you'll see how to do it in F#. This is essentially a port of the Haskell code.

Tree #

You can start by defining a rose tree:

type Tree<'a, 'b> = Node of 'a * Tree<'a, 'b> list | Leaf of 'b

If you wanted to, you could put all the Tree code in a reusable library, because none of it is coupled to a particular application, such as moving pictures. You could also write a comprehensive test suite for the following functions, but in this article, I'll skip that.

Notice that this sort of tree explicitly distinguishes between internal and leaf nodes. This is necessary because you'll need to keep track of the directory names (the internal nodes), while at the same time you'll want to enrich the leaves with additional data - data that you can't meaningfully add to the internal nodes. You'll see this later in the article.

While I typically tend to define F# types outside of modules (so that you don't have to, say, prefix the type name with the module name - Tree.Tree is so awkward), the rest of the tree code goes into a module, including two helper functions:

module Tree = // 'b -> Tree<'a,'b> let leaf = Leaf // 'a -> Tree<'a,'b> list -> Tree<'a,'b> let node x xs = Node (x, xs)

The leaf function doesn't add much value, but the node function offers a curried alternative to the Node case constructor. That's occasionally useful.

The rest of the code related to trees is also defined in the Tree module, but I'm going to present it formatted as free-standing functions. If you're confused about the layout of the code, the entire code base is available on GitHub.

The rose tree catamorphism is this cata function:

// ('a -> 'c list -> 'c) -> ('b -> 'c) -> Tree<'a,'b> -> 'c let rec cata fd ff = function | Leaf x -> ff x | Node (x, xs) -> xs |> List.map (cata fd ff) |> fd x

In the corresponding Haskell implementation of this architecture, I called this function foldTree, so why not retain that name? The short answer is that the naming conventions differ between Haskell and F#, and while I favour learning from Haskell, I still want my F# code to be as idiomatic as possible.

While I don't enforce that client code must use the Tree module name to access the functions within, I prefer to name the functions so that they make sense when used with qualified access. Having to write Tree.foldTree seems redundant. A more idiomatic name would be fold, so that you could write Tree.fold. The problem with that name, though, is that fold usually implies a list-biased fold (corresponding to foldl in Haskell), and I'll actually need that name for that particular purpose later.

So, cata it is.

In this article, tree functionality is (with one exception) directly or transitively implemented with cata.

Filtering trees #

It'll be useful to be able to filter the contents of a tree. For example, the picture archivist program will only move image files with valid metadata. This means that it'll need to filter out all files that aren't image files, as well as image files without valid metadata.

It turns out that it'll be useful to supply a function that throws away None values from a tree of option leaves. This is similar to List.choose, so I call it Tree.choose:

// ('a -> 'b option) -> Tree<'c,'a> -> Tree<'c,'b> option let choose f = cata (fun x -> List.choose id >> node x >> Some) (f >> Option.map Leaf)

You may find the type of the function surprising. Why does it return a Tree option, instead of simply a Tree?

While List.choose simply returns a list, it can do this because lists can be empty. This Tree type, on the other hand, can't be empty. If the purpose of Tree.choose is to throw away all None values, then how do you return a tree from Leaf None?

You can't return a Leaf because you have no value to put in the leaf. Similarly, you can't return a Node because, again, you have no value to put in the node.

In order to handle this edge case, then, you'll have to return None:

> let l : Tree<string, int option> = Leaf None;; val l : Tree<string,int option> = Leaf None > Tree.choose id l;; val it : Tree<string,int> option = None

If you have anything other than a None leaf, though, you'll get a proper tree, but wrapped in an option:

> Tree.node "Foo" [Leaf (Some 42); Leaf None; Leaf (Some 2112)] |> Tree.choose id;;

val it : Tree<string,int> option = Some (Node ("Foo",[Leaf 42; Leaf 2112]))

While the resulting tree is wrapped in a Some case, the leaves contain unwrapped values.

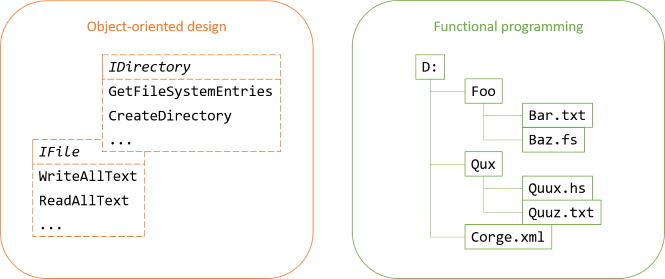

Bifunctor, functor, and folds #

Through its type class language feature, Haskell has formal definitions of functors, bifunctors, and other types of folds (list-biased catamorphisms). F# doesn't have a similar degree of formalism, which means that while you can still implement the corresponding functionality, you'll have to rely on conventions to make the functions recognisable.

It's straighforward to start with the bifunctor functionality:

// ('a -> 'b) -> ('c -> 'd) -> Tree<'a,'c> -> Tree<'b,'d> let bimap f g = cata (f >> node) (g >> leaf)

This is, apart from the syntax differences, the same implementation as in Haskell. Based on bimap, you can also trivially implement mapNode and mapLeaf functions if you'd like, but you're not going to need those for the code in this article. You do need, however, a function that we could consider an alias of a hypothetical mapLeaf function:

// ('b -> 'c) -> Tree<'a,'b> -> Tree<'a,'c> let map f = bimap id f

This makes Tree a functor.

It'll also be useful to reduce a tree to a potentially more compact value, so you can add some specialised folds:

// ('c -> 'a -> 'c) -> ('c -> 'b -> 'c) -> 'c -> Tree<'a,'b> -> 'c let bifold f g z t = let flip f x y = f y x cata (fun x xs -> flip f x >> List.fold (>>) id xs) (flip g) t z // ('a -> 'c -> 'c) -> ('b -> 'c -> 'c) -> Tree<'a,'b> -> 'c -> 'c let bifoldBack f g t z = cata (fun x xs -> List.foldBack (<<) xs id >> f x) g t z

In an attempt to emulate the F# naming conventions, I named the functions as I did. There are similar functions in the List and Option modules, for instance. If you're comparing the F# code with the Haskell code in the previous article, Tree.bifold corresponds to bifoldl, and Tree.bifoldBack corresponds to bifoldr.

These enable you to implement folds over leaves only:

// ('c -> 'b -> 'c) -> 'c -> Tree<'a,'b> -> 'c let fold f = bifold (fun x _ -> x) f // ('b -> 'c -> 'c) -> Tree<'a,'b> -> 'c -> 'c let foldBack f = bifoldBack (fun _ x -> x) f

These, again, enable you to implement another function that'll turn out to be useful in this article:

// ('b -> unit) -> Tree<'a,'b> -> unit let iter f = fold (fun () x -> f x) ()

The picture archivist program isn't going to explicitly need all of these, but transitively, it will.

Moving pictures #

So far, all the code shown here could be in a general-purpose reusable library, since it contains no functionality specifically related to image files. The rest of the code in this article, however, will be specific to the program. I'll put the domain model code in another module that I call Archive. Later in the article, we'll look at how to load a tree from the file system, but for now, we'll just pretend that we have such a tree.

The major logic of the program is to create a destination tree based on a source tree. The leaves of the tree will have to carry some extra information apart from a file path, so you can introduce a specific type to capture that information:

type PhotoFile = { File : FileInfo; TakenOn : DateTime }

A PhotoFile not only contains the file path for an image file, but also the date the photo was taken. This date can be extracted from the file's metadata, but that's an impure operation, so we'll delegate that work to the start of the program. We'll return to that later.

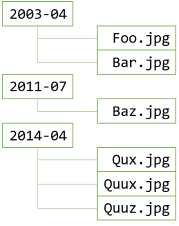

Given a source tree of PhotoFile leaves, though, the program must produce a destination tree of files:

// string -> Tree<'a,PhotoFile> -> Tree<string,FileInfo> let moveTo destination t = let dirNameOf (dt : DateTime) = sprintf "%d-%02d" dt.Year dt.Month let groupByDir pf m = let key = dirNameOf pf.TakenOn let dir = Map.tryFind key m |> Option.defaultValue [] Map.add key (pf.File :: dir) m let addDir name files dirs = Tree.node name (List.map Leaf files) :: dirs let m = Tree.foldBack groupByDir t Map.empty Map.foldBack addDir m [] |> Tree.node destination

This moveTo function looks, perhaps, overwhelming, but it's composed of three conceptual steps:

- Create a map of destination folders (

m). - Create a list of branches from the map (

Map.foldBack addDir m []). - Create a tree from the list (

Tree.node destination).

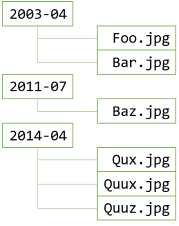

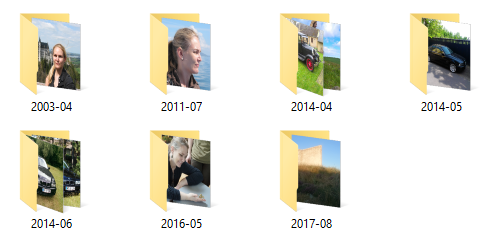

moveTo function starts by folding the input data into a map m. The map is keyed by the directory name, which is formatted by the dirNameOf function. This function takes a DateTime as input and formats it to a YYYY-MM format. For example, December 20, 2018 becomes "2018-12".

The entire mapping step groups the PhotoFile values into a map of the type Map<string,FileInfo list>. All the image files taken in April 2014 are added to the list with the "2014-04" key, all the image files taken in July 2011 are added to the list with the "2011-07" key, and so on.

In the next step, the moveTo function converts the map to a list of trees. This will be the branches (or sub-directories) of the destination directory. Because of the desired structure of the destination tree, this is a list of shallow branches. Each node contains only leaves.

The only remaining step is to add that list of branches to a destination node. This is done by piping (|>) the list of sub-directories into Tree.node destination.

Since this is a pure function, it's easy to unit test. Just create some test cases and call the function. First, the test cases.

In this code base, I'm using xUnit.net 2.4.1, so I'll first create a set of test cases as a test-specific class:

type MoveToDestinationTestData () as this = inherit TheoryData<Tree<string, PhotoFile>, string, Tree<string, string>> () let photoLeaf name (y, mth, d, h, m, s) = Leaf { File = FileInfo name; TakenOn = DateTime (y, mth, d, h, m, s) } do this.Add ( photoLeaf "1" (2018, 11, 9, 11, 47, 17), "D", Node ( "D", [Node ("2018-11", [Leaf "1"])])) do this.Add ( Node ("S", [photoLeaf "4" (1972, 6, 6, 16, 15, 0)]), "D", Node ("D", [Node ("1972-06", [Leaf "4"])])) do this.Add ( Node ("S", [ photoLeaf "L" (2002, 10, 12, 17, 16, 15); photoLeaf "J" (2007, 4, 21, 17, 18, 19)]), "D", Node ("D", [ Node ("2002-10", [Leaf "L"]); Node ("2007-04", [Leaf "J"])])) do this.Add ( Node ("1", [ photoLeaf "a" (2010, 1, 12, 17, 16, 15); photoLeaf "b" (2010, 3, 12, 17, 16, 15); photoLeaf "c" (2010, 1, 21, 17, 18, 19)]), "2", Node ("2", [ Node ("2010-01", [Leaf "a"; Leaf "c"]); Node ("2010-03", [Leaf "b"])])) do this.Add ( Node ("foo", [ Node ("bar", [ photoLeaf "a" (2010, 1, 12, 17, 16, 15); photoLeaf "b" (2010, 3, 12, 17, 16, 15); photoLeaf "c" (2010, 1, 21, 17, 18, 19)]); Node ("baz", [ photoLeaf "d" (2010, 3, 1, 2, 3, 4); photoLeaf "e" (2011, 3, 4, 3, 2, 1)])]), "qux", Node ("qux", [ Node ("2010-01", [Leaf "a"; Leaf "c"]); Node ("2010-03", [Leaf "b"; Leaf "d"]); Node ("2011-03", [Leaf "e"])]))

That looks like a lot of code, but is really just a list of test cases. Each test case is a triple of a source tree, a destination directory name, and an expected result (another tree).

The test itself, on the other hand, is compact:

[<Theory; ClassData(typeof<MoveToDestinationTestData>)>] let ``Move to destination`` source destination expected = let actual = Archive.moveTo destination source expected =! Tree.map string actual

The =! operator comes from Unquote and means something like must equal. It's an assertion that will throw an exception if expected isn't equal to Tree.map string actual.

The reason that the assertion maps actual to a tree of strings is that actual is a Tree<string,FileInfo>, but FileInfo doesn't have structural equality. So either I had to implement a test-specific equality comparer for FileInfo (and for Tree<string,FileInfo>), or map the tree to something with proper equality, such as a string. I chose the latter.

Calculating moves #

One pure step remains. The result of calling the moveTo function is a tree with the desired structure. In order to actually move the files, though, for each file you'll need to keep track of both the source path and the destination path. To make that explicit, you can define a type for that purpose:

type Move = { Source : FileInfo; Destination : FileInfo }

A Move is simply a data structure. Contrast this with typical object-oriented design, where it would be a (possibly polymorphic) method on an object. In functional programming, you'll regularly model intent with a data structure. As long as intents remain data, you can easily manipulate them, and once you're done with that, you can run an interpreter over your data structure to perform the work you want accomplished.

The unit test cases for the moveTo function suggest that file names are local file names like "L", "J", "a", and so on. That was only to make the tests as compact as possible, since the function actually doesn't manipulate the specific FileInfo objects.

In reality, the file names will most likely be longer, and they could also contain the full path, instead of the local path: "C:\foo\bar\a.jpg".

If you call moveTo with a tree where each leaf has a fully qualified path, the output tree will have the desired structure of the destination tree, but the leaves will still contain the full path to each source file. That means that you can calculate a Move for each file:

// Tree<string,FileInfo> -> Tree<string,Move> let calculateMoves = let replaceDirectory (f : FileInfo) d = FileInfo (Path.Combine (d, f.Name)) let rec imp path = function | Leaf x -> Leaf { Source = x; Destination = replaceDirectory x path } | Node (x, xs) -> let newNPath = Path.Combine (path, x) Tree.node newNPath (List.map (imp newNPath) xs) imp ""

This function takes as input a Tree<string,FileInfo>, which is compatible with the output of moveTo. It returns a Tree<string,Move>, i.e. a tree where the leaves are Move values.

Earlier, I wrote that you can implement desired Tree functionality with the cata function, but that was a simplification. If you can implement the functionality of calculateMoves with cata, I don't know how. You can, however, implement it using explicit pattern matching and simple recursion.

The imp function builds up a file path as it recursively negotiates the tree. All Leaf nodes are converted to a Move value using the leaf node's current FileInfo value as the Source, and the path to figure out the desired Destination.

This code is still easy to unit test. First, test cases:

type CalculateMovesTestData () as this = inherit TheoryData<Tree<string, FileInfo>, Tree<string, (string * string)>> () do this.Add (Leaf (FileInfo "1"), Leaf ("1", "1")) do this.Add ( Node ("a", [Leaf (FileInfo "1")]), Node ("a", [Leaf ("1", Path.Combine ("a", "1"))])) do this.Add ( Node ("a", [Leaf (FileInfo "1"); Leaf (FileInfo "2")]), Node ("a", [ Leaf ("1", Path.Combine ("a", "1")); Leaf ("2", Path.Combine ("a", "2"))])) do this.Add ( Node ("a", [ Node ("b", [ Leaf (FileInfo "1"); Leaf (FileInfo "2")]); Node ("c", [ Leaf (FileInfo "3")])]), Node ("a", [ Node (Path.Combine ("a", "b"), [ Leaf ("1", Path.Combine ("a", "b", "1")); Leaf ("2", Path.Combine ("a", "b", "2"))]); Node (Path.Combine ("a", "c"), [ Leaf ("3", Path.Combine ("a", "c", "3"))])]))

The test cases in this parametrised test are tuples of an input tree and the expected tree. For each test case, the test calls the Archive.calculateMoves function with tree and asserts that the actual tree is equal to the expected tree:

[<Theory; ClassData(typeof<CalculateMovesTestData>)>] let ``Calculate moves`` tree expected = let actual = Archive.calculateMoves tree expected =! Tree.map (fun m -> (m.Source.ToString (), m.Destination.ToString ())) actual

Again, the test maps FileInfo objects to strings to support easy comparison.

That's all the pure code you need in order to implement the desired functionality. Now you only need to write some code that loads a tree from disk, and imprints a destination tree to disk, as well as the code that composes it all.

Loading a tree from disk #

The remaining code in this article is impure. You could put it in dedicated modules, but for this program, you're only going to need three functions and a bit of composition code, so you could also just put it all in the Program module. That's what I did.

To load a tree from disk, you'll need a root directory, under which you load the entire tree. Given a directory path, you read a tree using a recursive function like this:

// string -> Tree<string,string> let rec readTree path = if File.Exists path then Leaf path else let dirsAndFiles = Directory.EnumerateFileSystemEntries path let branches = Seq.map readTree dirsAndFiles |> Seq.toList Node (path, branches)

This recursive function starts by checking whether the path is a file that exists. If it does, the path is a file, so it creates a new Leaf with that path.

If path isn't a file, it's a directory. In that case, use Directory.EnumerateFileSystemEntries to enumerate all the directories and files in that directory, and map all those directory entries recursively. That produces all the branches for the current node. Finally, return a new Node with the path and the branches.

Loading metadata #

The readTree function only produces a tree with string leaves, while the program requires a tree with PhotoFile leaves. You'll need to read the Exif metadata from each file and enrich the tree with the date-taken data.

In this code base, I've written a little Photo module to extract the desired metadata from an image file. I'm not going to list all the code here; if you're interested, the code is available on GitHub. The Photo module enables you to write an impure operation like this:

// FileInfo -> PhotoFile option let readPhoto file = Photo.extractDateTaken file |> Option.map (fun dateTaken -> { File = file; TakenOn = dateTaken })

This operation can fail for various reasons:

- The file may not exist.

- The file exists, but has no metadata.

- The file has metadata, but no date-taken metadata.

- The date-taken metadata string is malformed.

Tree<string,string> with readPhoto, you'll get a Tree<string,PhotoFile option>. That's when you'll need Tree.choose. You'll see this soon.

Writing a tree to disk #

The above calculateMoves function creates a Tree<string,Move>. The final piece of impure code you'll need to write is an operation that traverses such a tree and executes each Move.

// Tree<'a,Move> -> unit let writeTree t = let copy m = Directory.CreateDirectory m.Destination.DirectoryName |> ignore m.Source.CopyTo m.Destination.FullName |> ignore printfn "Copied to %s" m.Destination.FullName let compareFiles m = let sourceStream = File.ReadAllBytes m.Source.FullName let destinationStream = File.ReadAllBytes m.Destination.FullName sourceStream = destinationStream let move m = copy m if compareFiles m then m.Source.Delete () Tree.iter move t

The writeTree function traverses the input tree, and for each Move, it first copies the file, then it verifies that the copy was successful, and finally, if that's the case, it deletes the source file.

Composition #

You can now compose an impure-pure-impure sandwich from all the Lego pieces:

// string -> string -> unit let movePhotos source destination = let sourceTree = readTree source |> Tree.map FileInfo let photoTree = Tree.choose readPhoto sourceTree let destinationTree = Option.map (Archive.moveTo destination >> Archive.calculateMoves) photoTree Option.iter writeTree destinationTree

First, you load the sourceTree using the readTree operation. This returns a Tree<string,string>, so map the leaves to FileInfo objects. You then load the image metatadata by traversing sourceTree with Tree.choose readPhoto. Each call to readPhoto produces a PhotoFile option, so this is where you want to use Tree.choose to throw all the None values away.

Those two lines of code constitute the initial impure step of the sandwich (yes: mixed metaphors, I know).

The pure part of the sandwich is the composition of the pure functions moveTo and calculateMoves. Since photoTree is a Tree<string,PhotoFile> option, you'll need to perform that transformation inside of Option.map. The resulting destinationTree is a Tree<string,Move> option.

The final, impure step of the sandwich, then, is to apply all the moves with writeTree.

Execution #

The movePhotos operation takes source and destination arguments. You could hypothetically call it from a rich client or a background process, but here I'll just call if from a command-line program. The main operation will have to parse the input arguments and call movePhotos:

[<EntryPoint>] let main argv = match argv with | [|source; destination|] -> movePhotos source destination | _ -> printfn "Please provide source and destination directories as arguments." 0 // return an integer exit code

You could write more sophisticated parsing of the program arguments, but that's not the topic of this article, so I only wrote the bare minimum required to get the program working.

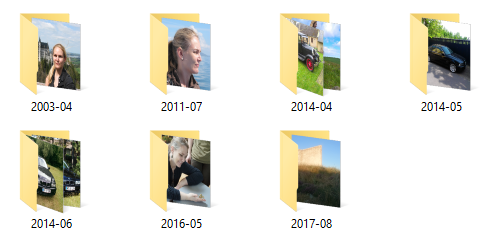

You can now compile and run the program:

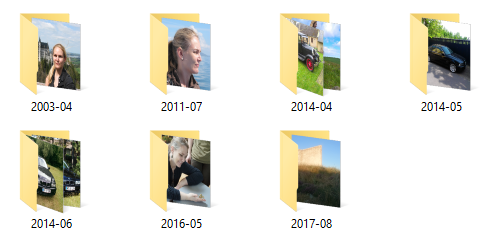

$ ./ArchivePictures "C:\Users\mark\Desktop\Test" "C:\Users\mark\Desktop\Test-Out" Copied to C:\Users\mark\Desktop\Test-Out\2003-04\2003-04-29 15.11.50.jpg Copied to C:\Users\mark\Desktop\Test-Out\2011-07\2011-07-10 13.09.36.jpg Copied to C:\Users\mark\Desktop\Test-Out\2014-04\2014-04-18 14.05.02.jpg Copied to C:\Users\mark\Desktop\Test-Out\2014-04\2014-04-17 17.11.40.jpg Copied to C:\Users\mark\Desktop\Test-Out\2014-05\2014-05-23 16.07.20.jpg Copied to C:\Users\mark\Desktop\Test-Out\2014-06\2014-06-21 16.48.40.jpg Copied to C:\Users\mark\Desktop\Test-Out\2014-06\2014-06-30 15.44.52.jpg Copied to C:\Users\mark\Desktop\Test-Out\2016-05\2016-05-01 09.25.23.jpg Copied to C:\Users\mark\Desktop\Test-Out\2017-08\2017-08-22 19.53.28.jpg

This does indeed produce the expected destination directory structure.

It's always nice when something turns out to work in practice, as well as in theory.

Summary #

Functional software architecture involves separating pure from impure code so that no pure functions invoke impure operations. Often, you can achieve that with what I call the impure-pure-impure sandwich architecture. In this example, you saw how to model the file system as a tree. This enables you to separate the impure file interactions from the pure program logic.

Comments

You do need, however, a function that we could consider an alias of a hypothetical

mapLeaffunction......

This makes

Treea functor.

I find that last statement slightly ambiguous. I prefer to say...

This makesTree<'a, 'b>a functor in'b.

...which is more precise.

In an attempt to emulate the F# naming conventions, I named the functions [bifoldandbifoldBack]. There are similar functions in theListandOptionmodules, for instance. If you're comparing the F# code with the Haskell code in the previous article,Tree.bifoldcorresponds tobifoldl, andTree.bifoldBackcorresponds tobifoldr.

I was very confused by these names at first. They suggest that the most important difference between them is the use of List.fold and List.foldBack in their respective implementations. However, for both bifold and bifoldBack, the behavior does not depend at all on the choice between List.fold and List.foldBack (as long as id and xs are given in the correct order). Instead, the difference between bifold and bifoldBack is completely determined by (the minor choice to use flip in bifold and) whether the function composition operator is to the right (as in bifold) or to the left (as in bifoldBack). This is slightly easier to see when bifoldBack is implemented as cata (fun x xs -> f x << List.foldBack (<<) xs id) g t z. The reason that the choice between List.fold and List.foldBack doesn't matter is because both function composition operators are associative (and because the seed value is the identity element for both functions).

The idea of a catamorphism is still very new to me. Instead of directly aggregating the parts of a tree into a single value like bifold and bifoldBack (via cata), I have historically exposed a minimal set of needed tree traversal orderings and then follow such a call with Seq.fold or Seq.foldBack. I think bifold does a preorder traversal and bifoldBack does a reverse preorder traversal. So, after all that, I now understand the names.

[The function

calculateMoves] takes as input aTree<string,FileInfo>, which is compatible with the output ofmoveTo. It returns aTree<string,Move>, i.e. a tree where the leaves areMovevalues.Earlier, I wrote that you can implement desired

Treefunctionality with thecatafunction, but that was a simplification. If you can implement the functionality ofcalculateMoveswithcata, I don't know how. You can, however, implement it using explicit pattern matching and simple recursion.The

impfunction builds up a file path as it recursively negotiates the tree. AllLeafnodes are converted to aMovevalue using the leaf node's currentFileInfovalue as theSource, and thepathto figure out the desiredDestination.

I don't know how to implement calculateMoves via cata either. Nonetheless, there is still a domain-independent abstraction waiting to be extracted.

Think of the scan function that exists in F# in the Seq and List modules. We can implement a similar function for your rose tree. I did so in this commit. Now calculateMoves is trivial, it still passes your domain-specific tests, and scan can be subjected to domain-independent unit tests.

Now the question is...can scan be implemented by cata? Or maybe...can cata be implemented by scan? I don't know the answer to either of these questions. Alternatively, we can ask...does scan correspond to some concept in category theory? I don't know that either. You are way ahead of me in your understanding of category theory, but I am doing my best to catch up.

Tyson, thank you for writing. That's a neat refactoring. I spent a couple of hours with it yesterday to see if I could implement your scan function with cata, but like you, it eludes me. It doesn't look like it's possible, although I'd love to be proven wrong.

I'm not aware of any theoretical foundations for scan, but there's so many things I don't know...

I originally came across the concept of F-Algebras and catamorphisms when I read Bartosz Milewski's article. I've later discovered that the recursion-schemes package was there all along. Not only does it define cata, but it also includes much other functionality that I still haven't absorbed. Perhaps there might be a clue there...

In this article, tree functionality is (with one exception) directly or transitively implemented with cata.

One tree functionality that this article didn't use is the apply function of an applicative functor. Of course apply can be implemented in terms of bind. Doing so here would yield an implementation of apply that transitively depends on cata.

Is there a way (perhaps an ellegant way) to directly implement apply via cata? I am asking because I have a monad with apply implemented in terms of bind, but I would like an implementation with better behavior.

Tyson, thank you for writing. Yes, you can implement the Applicative instance directly from the catamorphism.

Tyson, FWIW I figured out how to implement calculateMoves directly with the catamorphism.

Picture archivist in Haskell

A comprehensive code example showing how to implement a functional architecture in Haskell.

This article shows how to implement the picture archivist architecture described in the previous article. In short, the task is to move some image files to directories based on their date-taken metadata. The architectural idea is to load a directory structure from disk into an in-memory tree, manipulate that tree, and use the resulting tree to perform the desired actions:

Much of the program will manipulate the tree data, which is immutable.

Tree #

You can start by defining a rose tree:

data Tree a b = Node a [Tree a b] | Leaf b deriving (Eq, Show, Read)

If you wanted to, you could put all the Tree code in a reusable library, because none of it is coupled to a particular application, such as moving pictures. You could also write a comprehensive test suite for the following functions, but in this article, I'll skip that.