ploeh blog danish software design

Some thoughts on anti-patterns

What's an anti-pattern? Are there rules to identify them, or is it just name-calling? Before I use the term, I try to apply some rules of thumb.

It takes time to write a book. Months, even years. It took me two years to write the first edition of Dependency Injection in .NET. The second edition of Dependency Injection in .NET is also the result of much work; not so much by me, but by my co-author Steven van Deursen.

When you write a book single-handedly, you can be as opinionated as you'd like. When you have a co-author, regardless of how much you think alike, there's bound to be some disagreements. Steven and I agreed about most of the changes we'd like to make to the second edition, but each of us had to yield or compromise a few times.

An interesting experience has been that on more than one occasion where I've reluctantly had to yield to Steven, over the time, I've come to appreciate his position. Two minds think better than one.

Ambient Context #

One of the changes that Steven wanted to make was that he wanted to change the status of the Ambient Context pattern to an anti-pattern. While I never use that pattern myself, I included it in the first edition in the spirit of the original Design Patterns book. The Gang of Four made it clear that the patterns they'd described weren't invented, but rather discovered:

The spirit, as I understand it, is to identify solutions that already exist, and catalogue them. When I wrote the first edition of my book, I tried to do that as well."We have included only designs that have been applied more than once in different systems."

I'd noticed what I eventually named the Ambient Context pattern several places in the .NET Base Class Library. Some of those APIs are still around today. Thread.CurrentPrincipal, CultureInfo.CurrentCulture, thread-local storage, HttpContext.Current, and so on.

None of these really have anything to do with Dependency Injection (DI), but people sometimes attempt to use them to solve problems similar to the problems that DI addresses. For that reason, and because the pattern was so prevalent, I included it in the book - as a pattern, not an anti-pattern.

Steven wanted to make it an anti-pattern, and I conceded. I wasn't sure I was ready to explicitly call it out as an anti-pattern, but I agreed to the change. I'm becoming increasingly happy that Steven talked me into it.

Pareto efficiency #

I've heard said of me that I'm one of those people who call everything I don't like an anti-pattern. I don't think that's true.

I think people's perception of me is skewed because even today, the most visited page (my greatest hit, if you will) is an article called Service Locator is an Anti-Pattern. (It concerns me a bit that an article from 2010 seems to be my crowning achievement. I hope I haven't peaked yet, but the numbers tell a different tale.)

While I've used the term anti-pattern in other connections, I prefer to be conservative with my use of the word. I tend to use it only when I feel confident that something is, indeed, an anti-pattern.

What's an anti-pattern? AntiPatterns defines it like this:

As definitions go, it's quite amphibolous. Is it the problem that generates negative consequences? Hardly. In the context, it's clear that it's the solution that causes problems. In any case, just because it's in a book doesn't necessarily make it right, but I find it a good start."An AntiPattern is a literary form that describes a commonly occurring solution to a problem that generates decidedly negative consequences."

I think that the phrase decidedly negative consequences is key. Most solutions come with some disadvantages, but in order for a 'solution' to be an anti-pattern, the disadvantages must clearly outweigh any advantages produced.

I usually look at it another way. If I can solve the problem in a different way that generates at least as many advantages, but fewer disadvantages, then the first 'solution' might be an anti-pattern. This way of viewing the problem may stem from my background in economics. In that perspective, an anti-pattern simply isn't Pareto optimal.

Falsifiability #

Another rule of thumb I employ to determine whether a solution could be an anti-pattern is Popper's concept of falsifiability. As a continuation of the Pareto efficiency perspective, an anti-pattern is a 'solution' that you can improve without any (significant) trade-offs.

That turns claims about anti-patterns into falsifiable statements, which I consider is the most intellectually honest way to go about claiming that things are bad.

Take, for example, the claim that Service Locator is an anti-pattern. In light of Pareto efficiency, that's a falsifiable claim. All you have to do to prove me wrong is to present a situation where Service Locator solves a problem, and I can't come up with a better solution.

I made the claim about Service Locator in 2010, and so far, no one has been able to present such a situation, even though several have tried. I'm fairly confident making that claim.

This way of looking at the term anti-pattern, however, makes me wary of declaiming solutions anti-patterns just because I don't like them. Could there be a counter-argument, some niche scenario, where the pattern actually couldn't be improved without trade-offs?

I didn't take it lightly when Steven suggested making Ambient Context an anti-pattern.

Preliminary status #

I've had some time to think about Ambient Context since I had the (civil) discussion with Steven. The more I think about it, the more I think that he's right; that Ambient Context really is an anti-pattern.

I never use that pattern myself, so it's clear to me that for all the situations that I typically encounter, there's always better solutions, with no significant trade-offs.

The question is: could there be some niche scenario that I'm not aware of, where Ambient Context is a bona fide good solution?

The more I think about this, the more I'm beginning to believe that there isn't. It remains to be seen, though. It remains to be falsified.

Summary #

I'm so happy that Steven van Deursen agreed to co-author the second edition of Dependency Injection in .NET with me. The few areas where we've disagreed, I've ultimately come around to agree with him. He's truly taken a good book and made it better.

One of the changes is that Ambient Context is now classified as an anti-pattern. Originally, I wasn't sure that this was the correct thing to do, but I've since changed my mind. I do think that Ambient Context belongs in the anti-patterns chapter.

I could be wrong, though. I was before.

An Either functor

Either forms a normal functor. A placeholder article for object-oriented programmers.

This article is an instalment in an article series about functors. As another article explains, Either is a bifunctor. This makes it trivially a functor. As such, this article is mostly a place-holder to fit the spot in the functor table of contents, thereby indicating that Either is a functor.

Since Either is a bifunctor, it's actually not one, but two, functors. Many languages, C# included, are best equipped to deal with unambiguous functors. This is also true in Haskell, where Either l r is only a Functor over the right side. Likewise, in C#, you can make IEither<L, R> a functor by implementing Select:

public static IEither<L, R1> Select<L, R, R1>( this IEither<L, R> source, Func<R, R1> selector) { return source.SelectRight(selector); }

This method simply delegates all implementation to the SelectRight method; it's just SelectRight by another name. It obeys the functor laws, since these are just specializations of the bifunctor laws, and we know that Either is a proper bifunctor.

It would have been technically possible to instead implement a Select method by calling SelectLeft, but it seems generally more useful to enable syntactic sugar for mapping over 'happy path' scenarios. This enables you to write projections over operations that can fail.

Here's some C# Interactive examples that use the FindWinner helper method from the Church-encoded Either article. Imagine that you're collecting votes; you're trying to pick the highest-voted integer, but in reality, you're only interested in seeing if the number is positive or not. Since FindWinner returns IEither<VoteError, T>, and this type is a functor, you can project the right result, while any left result short-circuits the query. First, here's a successful query:

> from i in FindWinner(1, 2, -3, -1, 2, -1, -1) select i > 0 Right<VoteError, bool>(false)

This query succeeds, resulting in a Right object. The contained value is false because the winner of the vote is -1, which isn't a positive number.

On the other hand, the following query fails because of a tie.

> from i in FindWinner(1, 2, -3, -1, 2, -1) select i > 0 Left<VoteError, bool>(Tie)

Because the result is tied on -1, the return value is a Left object containing the VoteError value Tie.

Another source of error is an empty input collection:

> from i in FindWinner<int>() select i > 0 Left<VoteError, bool>(Empty)

This time, the Left object contains the Empty error value, since no winner can be found from an empty collection.

While the Select method doesn't implement any behaviour that SelectRight doesn't already afford, it enables you to use C# query syntax, as demonstrated by the above examples.

Next: A Tree functor.

Either bifunctor

Either forms a bifunctor. An article for object-oriented programmers.

This article is an instalment in an article series about bifunctors. As the overview article explains, essentially there's two practically useful bifunctors: pairs and Either. In the previous article, you saw how a pair (a two-tuple) forms a bifunctor. In this article, you'll see how Either also forms a bifunctor.

Mapping both dimensions #

In the previous article, you saw how, if you have maps over both dimensions, you can trivially implement SelectBoth (what Haskell calls bimap):

return source.SelectFirst(selector1).SelectSecond(selector2);

The relationship can, however, go both ways. If you implement SelectBoth, you can derive SelectFirst and SelectSecond from it. In this article, you'll see how to do that for Either.

Given the Church-encoded Either, the implementation of SelectBoth can be achieved in a single expression:

public static IEither<L1, R1> SelectBoth<L, L1, R, R1>( this IEither<L, R> source, Func<L, L1> selectLeft, Func<R, R1> selectRight) { return source.Match<IEither<L1, R1>>( onLeft: l => new Left<L1, R1>( selectLeft(l)), onRight: r => new Right<L1, R1>(selectRight(r))); }

Given that the input source is an IEither<L, R> object, there's isn't much you can do. That interface only defines a single member, Match, so that's the only method you can call. When you do that, you have to supply the two arguments onLeft and onRight.

The Match method is defined like this:

T Match<T>(Func<L, T> onLeft, Func<R, T> onRight)

Given the desired return type of SelectBoth, you know that T should be IEither<L1, R1>. This means, then, that for onLeft, you must supply a function of the type Func<L, IEither<L1, R1>>. Since a functor is a structure-preserving map, you should translate a left case to a left case, and a right case to a right case. This implies that the concrete return type that matches IEither<L1, R1> for the onLeft argument is Left<L1, R1>.

When you write the function with the type Func<L, IEither<L1, R1>> as a lambda expression, the input argument l has the type L. In order to create a new Left<L1, R1>, however, you need an L1 object. How do you produce an L1 object from an L object? You call selectLeft with l, because selectLeft is a function of the type Func<L, L1>.

You can apply the same line of reasoning to the onRight argument. Write a lambda expression that takes an R object r as input, call selectRight to turn that into an R1 object, and return it wrapped in a new Right<L1, R1> object.

This works as expected:

> new Left<string, int>("foo").SelectBoth(string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace, i => new DateTime(i)) Left<bool, DateTime>(false) > new Right<string, int>(1337).SelectBoth(string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace, i => new DateTime(i)) Right<bool, DateTime>([01.01.0001 00:00:00])

Notice that both of the above statements evaluated in C# Interactive use the same projections as input to SelectBoth. Clearly, though, because the inputs are first a Left value, and secondly a Right value, the outputs differ.

Mapping the left side #

When you have SelectBoth, you can trivially implement the translations for each dimension in isolation. In the previous article, I called these methods SelectFirst and SelectSecond. In this article, I've chosen to instead name them SelectLeft and SelectRight, but they still corresponds to Haskell's first and second Bifunctor functions.

public static IEither<L1, R> SelectLeft<L, L1, R>(this IEither<L, R> source, Func<L, L1> selector) { return source.SelectBoth(selector, r => r); }

The method body is literally a one-liner. Just call SelectBoth with selector as the projection for the left side, and the identity function as the projection for the right side. This ensures that if the actual value is a Right<L, R> object, nothing's going to happen. Only if the input is a Left<L, R> object will the projection run:

> new Left<string, int>("").SelectLeft(string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace) Left<bool, int>(true) > new Left<string, int>("bar").SelectLeft(string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace) Left<bool, int>(false) > new Right<string, int>(42).SelectLeft(string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace) Right<bool, int>(42)

In the above C# Interactive session, you can see how projecting three different objects using string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace works. When the Left object indeed does contain an empty string, the result is a Left value containing true. When the object contains "bar", however, it contains false. Furthermore, when the object is a Right value, the mapping has no effect.

Mapping the right side #

Similar to SelectLeft, you can also trivially implement SelectRight:

public static IEither<L, R1> SelectRight<L, R, R1>(this IEither<L, R> source, Func<R, R1> selector) { return source.SelectBoth(l => l, selector); }

This is another one-liner calling SelectBoth, with the difference that the identity function l => l is passed as the first argument, instead of as the last. This ensures that only Right values are mapped:

> new Left<string, int>("baz").SelectRight(i => new DateTime(i)) Left<string, DateTime>("baz") > new Right<string, int>(1_234_567_890).SelectRight(i => new DateTime(i)) Right<string, DateTime>([01.01.0001 00:02:03])

In the above examples, Right integers are projected into DateTime values, whereas Left strings stay strings.

Identity laws #

Either obeys all the bifunctor laws. While it's formal work to prove that this is the case, you can get an intuition for it via examples. Often, I use a property-based testing library like FsCheck or Hedgehog to demonstrate (not prove) that laws hold, but in this article, I'll keep it simple and only cover each law with a parametrised test.

private static T Id<T>(T x) => x; public static IEnumerable<object[]> BifunctorLawsData { get { yield return new[] { new Left<string, int>("foo") }; yield return new[] { new Left<string, int>("bar") }; yield return new[] { new Left<string, int>("baz") }; yield return new[] { new Right<string, int>( 42) }; yield return new[] { new Right<string, int>( 1337) }; yield return new[] { new Right<string, int>( 0) }; } } [Theory, MemberData(nameof(BifunctorLawsData))] public void SelectLeftObeysFirstFunctorLaw(IEither<string, int> e) { Assert.Equal(e, e.SelectLeft(Id)); }

This test uses xUnit.net's [Theory] feature to supply a small set of example input values. The input values are defined by the BifunctorLawsData property, since I'll reuse the same values for all the bifunctor law demonstration tests.

The tests also use the identity function implemented as a private function called Id, since C# doesn't come equipped with such a function in the Base Class Library.

For all the IEither<string, int> objects e, the test simply verifies that the original Either e is equal to the Either projected over the first axis with the Id function.

Likewise, the first functor law applies when translating over the second dimension:

[Theory, MemberData(nameof(BifunctorLawsData))] public void SelectRightObeysFirstFunctorLaw(IEither<string, int> e) { Assert.Equal(e, e.SelectRight(Id)); }

This is the same test as the previous test, with the only exception that it calls SelectRight instead of SelectLeft.

Both SelectLeft and SelectRight are implemented by SelectBoth, so the real test is whether this method obeys the identity law:

[Theory, MemberData(nameof(BifunctorLawsData))] public void SelectBothObeysIdentityLaw(IEither<string, int> e) { Assert.Equal(e, e.SelectBoth(Id, Id)); }

Projecting over both dimensions with the identity function does, indeed, return an object equal to the input object.

Consistency law #

In general, it shouldn't matter whether you map with SelectBoth or a combination of SelectLeft and SelectRight:

[Theory, MemberData(nameof(BifunctorLawsData))] public void ConsistencyLawHolds(IEither<string, int> e) { bool f(string s) => string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(s); DateTime g(int i) => new DateTime(i); Assert.Equal(e.SelectBoth(f, g), e.SelectRight(g).SelectLeft(f)); Assert.Equal( e.SelectLeft(f).SelectRight(g), e.SelectRight(g).SelectLeft(f)); }

This example creates two local functions f and g. The first function, f, just delegates to string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace, although I want to stress that this is just an example. The law should hold for any two (pure) functions. The second function, g, creates a new DateTime object from an integer, using one of the DateTime constructor overloads.

The test then verifies that you get the same result from calling SelectBoth as when you call SelectLeft followed by SelectRight, or the other way around.

Composition laws #

The composition laws insist that you can compose functions, or translations, and that again, the choice to do one or the other doesn't matter. Along each of the axes, it's just the second functor law applied. This parametrised test demonstrates that the law holds for SelectLeft:

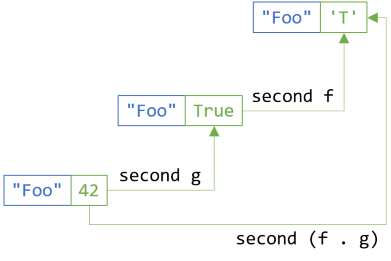

[Theory, MemberData(nameof(BifunctorLawsData))] public void SecondFunctorLawHoldsForSelectLeft(IEither<string, int> e) { bool f(int x) => x % 2 == 0; int g(string s) => s.Length; Assert.Equal(e.SelectLeft(x => f(g(x))), e.SelectLeft(g).SelectLeft(f)); }

Here, f is the even function, whereas g is a local function that returns the length of a string. The second functor law states that mapping f(g(x)) in a single step is equivalent to first mapping over g and then map the result of that using f.

The same law applies if you fix the first dimension and translate over the second:

[Theory, MemberData(nameof(BifunctorLawsData))] public void SecondFunctorLawHoldsForSelectRight(IEither<string, int> e) { char f(bool b) => b ? 'T' : 'F'; bool g(int i) => i % 2 == 0; Assert.Equal(e.SelectRight(x => f(g(x))), e.SelectRight(g).SelectRight(f)); }

Here, f is a local function that returns 'T' for true and 'F' for false, and g is a local function that, as you've seen before, determines whether a number is even. Again, the test demonstrates that the output is the same whether you map over an intermediary step, or whether you map using only a single step.

This generalises to the composition law for SelectBoth:

[Theory, MemberData(nameof(BifunctorLawsData))] public void SelectBothCompositionLawHolds(IEither<string, int> e) { bool f(int x) => x % 2 == 0; int g(string s) => s.Length; char h(bool b) => b ? 'T' : 'F'; bool i(int x) => x % 2 == 0; Assert.Equal( e.SelectBoth(x => f(g(x)), y => h(i(y))), e.SelectBoth(g, i).SelectBoth(f, h)); }

Again, whether you translate in one or two steps shouldn't affect the outcome.

As all of these tests demonstrate, the bifunctor laws hold for Either. The tests only showcase six examples for either a string or an integer, but I hope it gives you an intuition how any Either object is a bifunctor. After all, the SelectLeft, SelectRight, and SelectBoth methods are all generic, and they behave the same for all generic type arguments.

Summary #

Either objects are bifunctors. You can translate the first and second dimension of an Either object independently of each other, and the bifunctor laws hold for any pure translation, no matter how you compose the projections.

As always, there can be performance differences between the various compositions, but the outputs will be the same regardless of composition.

A functor, and by extension, a bifunctor, is a structure-preserving map. This means that any projection preserves the structure of the underlying container. For Either objects, it means that left objects remain left objects, and right objects remain right objects, even if the contained values change. Either is characterised by containing exactly one value, but it can be either a left value or a right value. No matter how you translate it, it still contains only a single value - left or right.

The other common bifunctor, pair, is complementary. Not only does it also have two dimensions, but a pair always contains both values at once.

Next: Rose tree bifunctor.

Comments

I feel like the concepts of functor and bifunctor were used somewhat interchangeably in this post. Can we clarify this relationship?

To help us with this, consider type variance. The generic type Func<A> is covariant, but more specifically, it is covariant on A. That additional prepositional phrase is often omitted because it can be inferred. In contrast, the generic type Func<A, B> is both covariant and contravariant but (of course) not on the same type parameter. It is covariant in B and contravariant in A.

I feel like saying that a generic type with two type parameters is a (bi)functor also needs an additional prepositional phrase. Like, Either<L, R> is a bifunctor in L and R, so it is also a functor in L and a functor in R.

Does this seem like a clearer way to talk about a specific type being both a bifunctor and a fuctor?

Tyson, thank you for writing. I find no fault with what you wrote. Is it clearer? I don't know.

One thing that's surprised me throughout this endeavour is exactly what does or doesn't confuse readers. This, I can't predict.

A functor is, by its definition, assumed to be covariant. Contravariant functors also exist, but they're explicitly named contravariant functors to distinguish them from standard functors.

Ultimately, co- or contravariance of generic type arguments is (I think) insufficient to identify a type as a functor. Whether or not something is a functor is determined by whether or not it obeys the functor laws. Can we guarantee that all types with a covariant type argument will obey the functor laws?

I wasn't trying to discuss the relationship between functors and type variance. I just brought up type variance as an example in programming where I think adding additional prepositional phrases to statements can clarify things.

Tuple bifunctor

A Pair (a two-tuple) forms a bifunctor. An article for object-oriented programmers.

This article is an instalment in an article series about bifunctors. In the previous overview, you learned about the general concept of a bifunctor. In practice, there's two useful bifunctor instances: pairs (two-tuples) and Either. In this article, you'll see how a pair is a bifunctor, and in the next article, you'll see how Either fits the same abstraction.

Tuple as a functor #

You can treat a normal pair (two-tuple) as a functor by mapping one of the elements, while keeping the other generic type fixed. In Haskell, when you have types with multiple type arguments, you often 'fix' the types from the left, leaving the right-most type free to vary. Doing this for a pair, which in C# has the type Tuple<T, U>, this means that tuples are functors if we keep T fixed and enable translation of the second element from U1 to U2.

This is easy to implement with a standard Select extension method:

public static Tuple<T, U2> Select<T, U1, U2>( this Tuple<T, U1> source, Func<U1, U2> selector) { return Tuple.Create(source.Item1, selector(source.Item2)); }

You simply return a new tuple by carrying source.Item1 over without modification, while on the other hand calling selector with source.Item2. Here's a simple example, which also highlights that C# understands functors:

var t = Tuple.Create("foo", 42); var actual = from i in t select i % 2 == 0;

Here, actual is a Tuple<string, bool> with the values "foo" and true. Inside the query expression, i is an int, and the select expression returns a bool value indicating whether the number is even or odd. Notice that the string in the first element disappears inside the query expression. It's still there, but the code inside the query expression can't see "foo".

Mapping the first element #

There's no technical reason why the mapping has to be over the second element; it's just how Haskell does it by convention. There are other, more philosophical reasons for that convention, but in the end, they boil down to the ultimately arbitrary cultural choice of reading from left to right (in Western scripts).

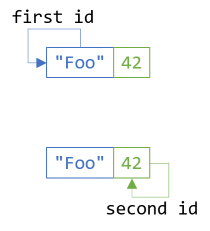

You can translate the first element of a tuple as easily:

public static Tuple<T2, U> SelectFirst<T1, T2, U>( this Tuple<T1, U> source, Func<T1, T2> selector) { return Tuple.Create(selector(source.Item1), source.Item2); }

While, technically, you can call this method Select, this can confuse the C# compiler's overload resolution system - at least if you have a tuple of two identical types (e.g. Tuple<int, int> or Tuple<string, string>). In order to avoid that sort of confusion, I decided to give the method another name, and in keeping with how C# LINQ methods tend to get names, I thought SelectFirst sounded reasonable.

In Haskell, this function is called first, and is part of the Bifunctor type class:

Prelude Data.Bifunctor> first (even . length) ("foo", 42)

(False,42)

In C#, you can perform the same translation using the above SelectFirst extension method:

var t = Tuple.Create("foo", 42); var actual = t.SelectFirst(s => s.Length % 2 == 0);

This also returns a Tuple<bool, int> containing the values false and 42. Notice that in this case, the first element "foo" is translated into false (because its length is odd), while the second element 42 carries over unchanged.

Mapping the second element #

You've already seen how the above Select method maps over the second element of a pair. This means that you can already map over both dimensions of the bifunctor, but perhaps, for consistency's sake, you'd also like to add an explicit SelectSecond method. This is now trivial to implement, since it can delegate its work to Select:

public static Tuple<T, U2> SelectSecond<T, U1, U2>( this Tuple<T, U1> source, Func<U1, U2> selector) { return source.Select(selector); }

There's no separate implementation; the only thing this method does is to delegate work to the Select method. It's literally the Select method, just with another name.

Clearly, you could also have done it the other way around: implement SelectSecond and then call it from Select.

The SelectSecond method works as you'd expect:

var t = Tuple.Create("foo", 1337); var actual = t.SelectSecond(i => i % 2 == 0);

Again, actual is a tuple containing the values "foo" and false, because 1337 isn't even.

This fits with the Haskell implementation, where SelectSecond is called second:

Prelude Data.Bifunctor> second even ("foo", 1337)

("foo",False)

The result is still a pair where the first element is "foo" and the second element False, exactly like in the C# example.

Mapping both elements #

With SelectFirst and SelectSecond, you can trivially implement SelectBoth:

public static Tuple<T2, U2> SelectBoth<T1, T2, U1, U2>( this Tuple<T1, U1> source, Func<T1, T2> selector1, Func<U1, U2> selector2) { return source.SelectFirst(selector1).SelectSecond(selector2); }

This method takes two translations, selector1 and selector2, and first uses SelectFirst to project along the first axis, and then SelectSecond to map the second dimension.

This implementation creates an intermediary pair that callers never see, so this could theoretically be inefficient. In this article, however, I want to show you that it's possible to implement SelectBoth based on SelectFirst and SelectSecond. In the next article, you'll see how to do it the other way around.

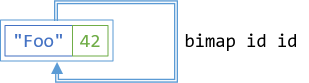

Using SelectBoth is easy:

var t = Tuple.Create("foo", 42); var actual = t.SelectBoth(s => s.First(), i => i % 2 == 0);

This translation returns a pair where the first element is 'f' and the second element is true. This is because the first lambda expression s => s.First() returns the first element of the input string "foo", whereas the second lambda expression i => i % 2 == 0 determines that 42 is even.

In Haskell, SelectBoth is called bimap:

Prelude Data.Bifunctor> bimap head even ("foo", 42)

('f',True)

The return value is consistent with the C# example, since the input is also equivalent.

Identity laws #

Pairs obey all the bifunctor laws. While it's formal work to prove that this is the case, you can get an intuition for it via examples. Often, I use a property-based testing library like FsCheck or Hedgehog to demonstrate (not prove) that laws hold, but in this article, I'll keep it simple and only cover each law with a parametrised test.

private static T Id<T>(T x) => x; [Theory] [InlineData("foo", 42)] [InlineData("bar", 1337)] [InlineData("foobar", 0)] [InlineData("ploeh", 7)] [InlineData("fnaah", -6)] public void SelectFirstObeysFirstFunctorLaw(string first, int second) { var t = Tuple.Create(first, second); Assert.Equal(t, t.SelectFirst(Id)); }

This test uses xUnit.net's [Theory] feature to supply a small set of example input values. It defines the identity function as a private function called Id, since C# doesn't come equipped with such a function in the Base Class Library.

The test simply creates a tuple with the input values and verifies that the original tuple t is equal to the tuple projected over the first axis with the Id function.

Likewise, the first functor law applies when translating over the second dimension:

[Theory] [InlineData("foo", 42)] [InlineData("bar", 1337)] [InlineData("foobar", 0)] [InlineData("ploeh", 7)] [InlineData("fnaah", -6)] public void SelectSecondObeysFirstFunctorLaw(string first, int second) { var t = Tuple.Create(first, second); Assert.Equal(t, t.SelectSecond(Id)); }

This is the same test as the previous test, with the only exception that it calls SelectSecond instead of SelectFirst.

Since SelectBoth in this example is implemented by composing SelectFirst and SelectSecond, you should expect it to obey the general identity law for bifunctors. It does, but it's always nice to see it with your own eyes:

[Theory] [InlineData("foo", 42)] [InlineData("bar", 1337)] [InlineData("foobar", 0)] [InlineData("ploeh", 7)] [InlineData("fnaah", -6)] public void SelectBothObeysIdentityLaw(string first, int second) { var t = Tuple.Create(first, second); Assert.Equal(t, t.SelectBoth(Id, Id)); }

Here you can see that projecting over both dimensions with the identity function returns the original tuple.

Consistency law #

In general, it shouldn't matter whether you map with SelectBoth or a combination of SelectFirst and SelectSecond:

[Theory] [InlineData("foo", 42)] [InlineData("bar", 1337)] [InlineData("foobar", 0)] [InlineData("ploeh", 7)] public void ConsistencyLawHolds(string first, int second) { Func<string, bool> f = string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace; Func<int, DateTime> g = i => new DateTime(i); var t = Tuple.Create(first, second); Assert.Equal( t.SelectBoth(f, g), t.SelectSecond(g).SelectFirst(f)); Assert.Equal( t.SelectFirst(f).SelectSecond(g), t.SelectSecond(g).SelectFirst(f)); }

This example creates two functions f and g. The first function, f, is just an alias for string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace, although I want to stress that it's just an example. The law should hold for any two (pure) functions. The second function, g, creates a new DateTime object from an integer, using one of the DateTime constructor overloads.

The test then verifies that you get the same result from calling SelectBoth as when you call SelectFirst followed by SelectSecond, or the other way around.

Composition laws #

The composition laws insist that you can compose functions, or translations, and that again, the choice to do one or the other doesn't matter. Along each of the axes, it's just the second functor law applied. You've already seen that SelectSecond is nothing but an alias for Select, so surely, the second functor law must hold for SelectSecond as well. This parametrised test demonstrates that it does:

[Theory] [InlineData("foo", 42)] [InlineData("bar", 1337)] [InlineData("foobar", 0)] [InlineData("ploeh", 7)] [InlineData("fnaah", -6)] public void SecondFunctorLawHoldsForSelectSecond(string first, int second) { Func<bool, char> f = b => b ? 'T' : 'F'; Func<int, bool> g = i => i % 2 == 0; var t = Tuple.Create(first, second); Assert.Equal( t.SelectSecond(x => f(g(x))), t.SelectSecond(g).SelectSecond(f)); }

Here, f is a function that returns 'T' for true and 'F' for false, and g is a function that, as you've seen before, determines whether a number is even. The second functor law states that mapping f(g(x)) in a single step is equivalent to first mapping over g and then map the result of that using f.

The same law applies if you fix the second dimension and translate over the first:

[Theory] [InlineData("foo", 42)] [InlineData("bar", 1337)] [InlineData("foobar", 0)] [InlineData("ploeh", 7)] [InlineData("fnaah", -6)] public void SecondFunctorLawHoldsForSelectFirst(string first, int second) { Func<int, bool> f = x => x % 2 == 0; Func<string, int> g = s => s.Length; var t = Tuple.Create(first, second); Assert.Equal( t.SelectFirst(x => f(g(x))), t.SelectFirst(g).SelectFirst(f)); }

Here, f is the even function, whereas g is a function that returns the length of a string. Again, the test demonstrates that the output is the same whether you map over an intermediary step, or whether you map using only a single step.

This generalises to the composition law for SelectBoth:

[Theory] [InlineData("foo", 42)] [InlineData("bar", 1337)] [InlineData("foobar", 0)] [InlineData("ploeh", 7)] [InlineData("fnaah", -6)] public void SelectBothCompositionLawHolds(string first, int second) { Func<int, bool> f = x => x % 2 == 0; Func<string, int> g = s => s.Length; Func<bool, char> h = b => b ? 'T' : 'F'; Func<int, bool> i = x => x % 2 == 0; var t = Tuple.Create(first, second); Assert.Equal( t.SelectBoth(x => f(g(x)), y => h(i(y))), t.SelectBoth(g, i).SelectBoth(f, h)); }

Again, whether you translate in one or two steps shouldn't affect the outcome.

As all of these tests demonstrate, the bifunctor laws hold for pairs. The tests only showcase 4-5 examples for a pair of string and integer, but I hope it gives you an intuition how any pair is a bifunctor. After all, the SelectFirst, SelectSecond, and SelectBoth methods are all generic, and they behave the same for all generic type arguments.

Summary #

Pairs (two-tuples) are bifunctors. You can translate the first and second element of a pair independently of each other, and the bifunctor laws hold for any pure translation, no matter how you compose the projections.

As always, there can be performance differences between the various compositions, but the outputs will be the same regardless of composition.

A functor, and by extension, a bifunctor, is a structure-preserving map. This means that any projection preserves the structure of the underlying container. In practice that means that for pairs, no matter how you translate a pair, it remains a pair. A pair is characterised by containing two values at once, and no matter how you translate it, it'll still contain two values.

The other common bifunctor, Either, is complementary. While it has two dimensions, it only contains one value, which is of either the one type or the other. It's still a bifunctor, though, because mappings preserve the structure of Either, too.

Next: Either bifunctor.

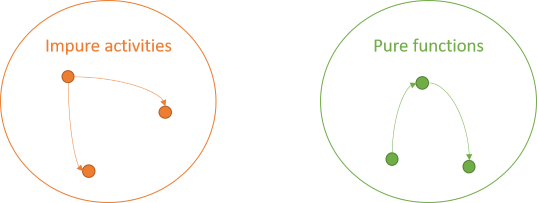

Bifunctors

Bifunctors are like functors, only they vary in two dimensions instead of one. An article for object-oriented programmers.

This article is a continuation of the article series about functors and about applicative functors. In this article, you'll learn about a generalisation called a bifunctor. The prefix bi typically indicates that there's two of something, and that's also the case here.

As you've already seen in the functor articles, a functor is a mappable container of generic values, like Foo<T>, where the type of the contained value(s) can be any generic type T. A bifunctor is just a container with two independent generic types, like Bar<T, U>. If you can map each of the types independently of the other, you may have a bifunctor.

The two most common bifunctors are tuples and Either.

Maps #

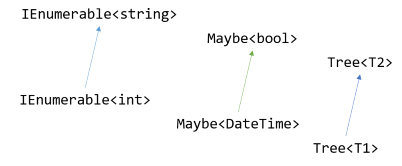

A normal functor is based on a structure-preserving map of the contents within a container. You can, for example, translate an IEnumerable<int> to an IEnumerable<string>, or a Maybe<DateTime> to a Maybe<bool>. The axis of variability is the generic type argument T. You can translate T1 to T2 inside a container, but the type of the container remains the same: you can translate Tree<T1> to Tree<T2>, but it remains a Tree<>.

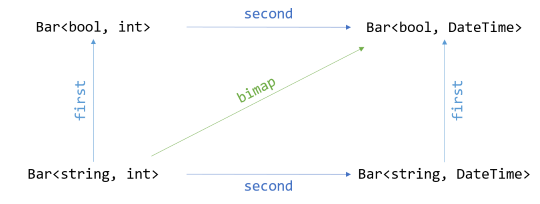

A bifunctor involves a pair of maps, one for each generic type. You can map a Bar<string, int> to a Bar<bool, int>, or to a Bar<string, DateTime>, or even to a Bar<bool, DateTime>. Notice that the last example, mapping from Bar<string, int> to Bar<bool, DateTime> could be viewed as translating both axes simultaneously.

In Haskell, the two maps are called first and second, while the 'simultaneous' map is called bimap.

The first translation translates the first, or left-most, value in the container. You can use it to map Bar<string, int> to a Bar<bool, int>. In C#, we could decide to call the method SelectFirst, or SelectLeft, in order to align with the C# naming convention of calling the functor morphism Select.

Likewise, the second map translates the second, or right-most, value in the container. This is where you map Bar<string, int> to Bar<string, DateTime>. In C#, we could call the method SelectSecond, or SelectRight.

The bimap function maps both values in the container in one go. This corresponds to a translation from Bar<string, int> to Bar<bool, DateTime>. In C#, we could call the method SelectBoth. There's no established naming conventions for bifunctors in C# that I know of, so these names are just some that I made up.

You'll see examples of how to implement and use such functions in the next articles:

Other bifunctors exist, but the first two are the most common.Identity laws #

As is the case with functors, laws govern bifunctors. Some of the functor laws carry over, but are simply repeated over both axes, while other laws are generalisations of the functor laws. For example, the first functor law states that if you translate a container with the identity function, the result is the original input. This generalises to bifunctors as well:

bimap id id ≡ id

This just states that if you translate both axes using the endomorphic Identity, it's equivalent to applying the Identity.

Using C# syntax, you could express the law like this:

bf.SelectBoth(id, id) == bf;

Here, bf is some bifunctor, and id is the identity function. The point is that if you translate over both axes, but actually don't perform a real translation, nothing happens.

Likewise, if you consider a bifunctor a functor over two dimensions, the first functor law should hold for both:

first id ≡ id second id ≡ id

Both of those equalities only restate the first functor law for each dimension. If you map an axis with the identity function, nothing happens:

In C#, you can express both laws like this:

bf.SelectFirst(id) == bf; bf.SelectSecond(id) == bf;

When calling SelectFirst, you translate only the first axis while you keep the second axis constant. When calling SelectSecond it's the other way around: you translate only the second axis while keeping the first axis constant. In both cases, though, if you use the identity function for the translation, you effectively keep the mapped dimension constant as well. Therefore, one would expect the result to be the same as the input.

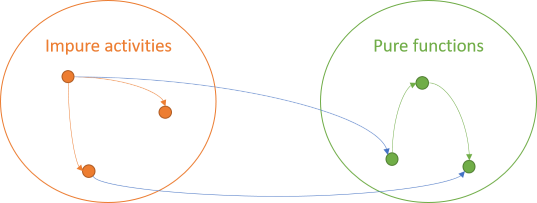

Consistency law #

As you'll see in the articles on tuple and Either bifunctors, you can derive bimap or SelectBoth from first/SelectFirst and second/SelectSecond, or the other way around. If, however, you decide to implement all three functions, they must act in a consistent manner. The name Consistency law, however, is entirely my own invention. If it has a more well-known name, I'm not aware of it.

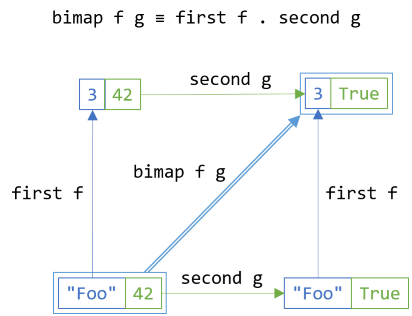

In pseudo-Haskell syntax, you can express the law like this:

bimap f g ≡ first f . second g

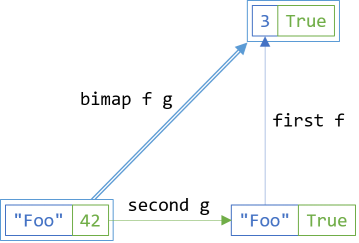

This states that mapping (using the functions f and g) simultaneously should produce the same result as mapping using an intermediary step:

In C#, you could express it like this:

bf.SelectBoth(f, g) == bf.SelectSecond(g).SelectFirst(f);

You can project the input bifunctor bf using both f and g in a single step, or you can first translate the second dimension with g and then subsequently map that intermediary result along the first axis with f.

The above diagram ought to commute:

It shouldn't matter whether the intermediary step is applying f along the first axis or g along the second axis. In C#, we can write it like this:

bf.SelectFirst(f).SelectSecond(g) == bf.SelectSecond(g).SelectFirst(f);

On the left-hand side, you first translate the bifunctor bf along the first axis, using f, and then translate that intermediary result along the second axis, using g. On the right-hand side, you first project bf along the second axis, using g, and then map that intermediary result over the first dimension, using f.

Regardless of order of translation, the result should be the same.

Composition laws #

Similar to how the first functor law generalises to bifunctors, the second functor law generalises as well. For (mono)functors, the second functor law states that if you have two functions over the same dimension, it shouldn't matter whether you perform a projection in one, composed step, or in two steps with an intermediary result.

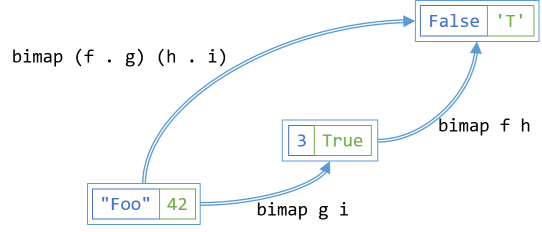

For bifunctors, you can generalise that law and state that you can project over both dimensions in one or two steps:

bimap (f . g) (h . i) ≡ bimap f h . bimap g i

If you have two functions, f and g, that compose, and two other functions, h and i, that also compose, you can translate in either one or two steps; the result should be the same.

In C#, you can express the law like this:

bf.SelectBoth(x => f(g(x)), y => h(i(y))) == bf.SelectBoth(g, i).SelectBoth(f, h);

On the left-hand side, the first dimension is translated in one step. For each x contained in bf, the translation first invokes g(x), and then immediately calls f with the output of g(x). The second dimension also gets translated in one step. For each y contained in bf, the translation first invokes i(y), and then immediately calls h with the output of i(y).

On the right-hand side, you first translate bf along both axes using g and i. This produces an intermediary result that you can use as input for a second translation with f and h.

The translation on the left-hand side should produce the same output as the right-hand side.

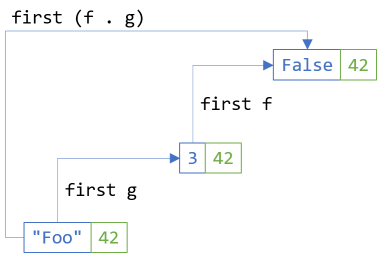

Finally, if you keep one of the dimensions fixed, you essentially have a normal functor, and the second functor law should still hold. For example, if you hold the second dimension fixed, translating over the first dimension is equivalent to a normal functor projection, so the second functor law should hold:

first (f . g) ≡ first f . first g

If you replace first with fmap, you have the second functor law.

In C#, you can write it like this:

bf.SelectFirst(x => f(g(x))) == bf.SelectFirst(g).SelectFirst(f);

Likewise, you can keep the first dimension constant and apply the second functor law to projections along the second axis:

second (f . g) ≡ second f . second g

Again, if you replace second with fmap, you have the second functor law.

In C#, you express it like this:

bf.SelectSecond(x => f(g(x))) == bf.SelectSecond(g).SelectSecond(f);

The last two of these composition laws are specialisations of the general composition law, but where you fix either one or the other dimension.

Summary #

A bifunctor is a container that can be translated over two dimensions, instead of a (mono)functor, which is a container that can be translated over a single dimension. In reality, there isn't a multitude of different bifunctors. While others exist, tuples and Either are the two most common bifunctors. They share an abstraction, but are still fundamentally different. A tuple always contains values of both dimensions at the same time, whereas Either only contains one of the values.

Do trifunctors, quadfunctors, and so on, exist? Nothing prevents that, but they aren't particularly useful; in practice, you never run into them.

Next: Tuple bifunctor.

The Lazy applicative functor

Lazy computations form an applicative functor.

This article is an instalment in an article series about applicative functors. A previous article has described how lazy computations form a functor. In this article, you'll see that lazy computations also form an applicative functor.

Apply #

As you have previously seen, C# isn't the best fit for the concept of applicative functors. Nevertheless, you can write an Apply extension method following the applicative 'code template':

public static Lazy<TResult> Apply<TResult, T>( this Lazy<Func<T, TResult>> selector, Lazy<T> source) { return new Lazy<TResult>(() => selector.Value(source.Value)); }

The Apply method takes both a lazy selector and a lazy value called source. It applies the function to the value and returns the result, still as a lazy value. If you have a lazy function f and a lazy value x, you can use the method like this:

Lazy<Func<int, string>> f = // ... Lazy<int> x = // ... Lazy<string> y = f.Apply(x);

The utility of Apply, however, mostly tends to emerge when you need to chain multiple containers together; in this case, multiple lazy values. You can do that by adding as many overloads to Apply as you need:

public static Lazy<Func<T2, TResult>> Apply<T1, T2, TResult>( this Lazy<Func<T1, T2, TResult>> selector, Lazy<T1> source) { return new Lazy<Func<T2, TResult>>(() => y => selector.Value(source.Value, y)); }

This overload partially applies the input function. When selector is a function that takes two arguments, you can apply a single of those two arguments, and the result is a new function that closes over the value, but still waits for its second input argument. You can use it like this:

Lazy<Func<char, int, string>> f = // ... Lazy<char> c = // ... Lazy<int> i = // ... Lazy<string> s = f.Apply(c).Apply(i);

Notice that you can chain the various overloads of Apply. In the above example, you have a lazy function that takes a char and an int as input, and returns a string. It could, for instance, be a function that invokes the equivalent string constructor overload.

Calling f.Apply(c) uses the overload that takes a Lazy<Func<T1, T2, TResult>> as input. The return value is a Lazy<Func<int, string>>, which the first Apply overload then picks up, to return a Lazy<string>.

Usually, you may have one, two, or several lazy values, whereas your function itself isn't contained in a Lazy container. While you can use a helper method such as Lazy.FromValue to 'elevate' a 'normal' function to a lazy function value, it's often more convenient if you have another Apply overload like this:

public static Lazy<Func<T2, TResult>> Apply<T1, T2, TResult>( this Func<T1, T2, TResult> selector, Lazy<T1> source) { return new Lazy<Func<T2, TResult>>(() => y => selector(source.Value, y)); }

The only difference to the equivalent overload is that in this overload, selector isn't a Lazy value, while source still is. This simplifies usage:

Func<char, int, string> f = // ... Lazy<char> c = // ... Lazy<int> i = // ... Lazy<string> s = f.Apply(c).Apply(i);

Notice that in this variation of the example, f is no longer a Lazy<Func<...>>, but just a normal Func.

F# #

F#'s type inference is more powerful than C#'s, so you don't have to resort to various overloads to make things work. You could, for example, create a minimal Lazy module:

module Lazy = // ('a -> 'b) -> Lazy<'a> -> Lazy<'b> let map f (x : Lazy<'a>) = lazy f x.Value // Lazy<('a -> 'b)> -> Lazy<'a> -> Lazy<'b> let apply (x : Lazy<_>) (f : Lazy<_>) = lazy f.Value x.Value

In this code listing, I've repeated the map function shown in a previous article. It's not required for the implementation of apply, but you'll see it in use shortly, so I thought it was convenient to include it in the listing.

If you belong to the camp of F# programmers who think that F# should emulate Haskell, you can also introduce an operator:

let (<*>) f x = Lazy.apply x f

Notice that this <*> operator simply flips the arguments of Lazy.apply. If you introduce such an operator, be aware that the admonition from the overview article still applies. In Haskell, the <*> operator applies to any Applicative, which makes it truly general. In F#, once you define an operator like this, it applies specifically to a particular container type, which, in this case, is Lazy<'a>.

You can replicate the first of the above C# examples like this:

let f : Lazy<int -> string> = // ... let x : Lazy<int> = // ... let y : Lazy<string> = Lazy.apply x f

Alternatively, if you want to use the <*> operator, you can compute y like this:

let y : Lazy<string> = f <*> x

Chaining multiple lazy computations together also works:

let f : Lazy<char -> int -> string> = // ... let c : Lazy<char> = // ... let i : Lazy<int> = // ... let s = Lazy.apply c f |> Lazy.apply i

Again, you can compute s with the operator, if that's more to your liking:

let s : Lazy<string> = f <*> c <*> i

Finally, if your function isn't contained in a Lazy value, you can start out with Lazy.map:

let f : char -> int -> string = // ... let c : Lazy<char> = // ... let i : Lazy<int> = // ... let s : Lazy<string> = Lazy.map f c |> Lazy.apply i

This works without requiring additional overloads. Since F# natively supports partial function application, the first step in the pipeline, Lazy.map f c has the type Lazy<int -> string> because f is a function of the type char -> int -> string, but in the first step, Lazy.map f c only supplies c, which contains a char value.

Once more, if you prefer the infix operator, you can also compute s as:

let s : Lazy<string> = lazy f <*> c <*> i

While I find operator-based syntax attractive in Haskell code, I'm more hesitant about such syntax in F#.

Haskell #

As outlined in the previous article, Haskell is already lazily evaluated, so it makes little sense to introduce an explicit Lazy data container. While Haskell's built-in Identity isn't quite equivalent to .NET's Lazy<T> object, some similarities remain; most notably, the Identity functor is also applicative:

Prelude Data.Functor.Identity> :t f f :: a -> Int -> [a] Prelude Data.Functor.Identity> :t c c :: Identity Char Prelude Data.Functor.Identity> :t i i :: Num a => Identity a Prelude Data.Functor.Identity> :t f <$> c <*> i f <$> c <*> i :: Identity String

This little GHCi session simply illustrates that if you have a 'normal' function f and two Identity values c and i, you can compose them using the infix map operator <$>, followed by the infix apply operator <*>. This is equivalent to the F# expression Lazy.map f c |> Lazy.apply i.

Still, this makes little sense, since all Haskell expressions are already lazily evaluated.

Summary #

The Lazy functor is also an applicative functor. This can be used to combine multiple lazily computed values into a single lazily computed value.

Next: Applicative monoids.

Danish CPR numbers in F#

An example of domain-modelling in F#, including a fine example of using the option type as an applicative functor.

This article is an instalment in an article series about applicative functors, although the applicative functor example doesn't appear until towards the end. This article also serves the purpose of showing an example of Domain-Driven Design in F#.

Danish personal identification numbers #

As outlined in the previous article, in Denmark, everyone has a personal identification number, in Danish called CPR-nummer (CPR number).

CPR numbers have a simple format: DDMMYY-SSSS, where the first six digits indicate a person's birth date, and the last four digits are a sequence number. Some information, however, is also embedded in the sequence number. An example could be 010203-1234, which indicates a woman born February 1, 1903.

One way to model this in F# is with a single-case discriminated union:

type CprNumber = private CprNumber of (int * int * int * int) with override x.ToString () = let (CprNumber (day, month, year, sequenceNumber)) = x sprintf "%02d%02d%02d-%04d" day month year sequenceNumber

This is a common idiom in F#. In object-oriented design with e.g. C# or Java, you'd typically create a class and put guard clauses in its constructor. This would prevent a user from initialising an object with invalid data (such as 401500-1234). While you can create classes in F# as well, a single-case union with a private case constructor can achieve the same degree of encapsulation.

In this case, I decided to use a quadruple (4-tuple) as the internal representation, but this isn't visible to users. This gives me the option to refactor the internal representation, if I need to, without breaking existing clients.

Creating CPR number values #

Since the CprNumber case constructor is private, you can't just create new values like this:

let cpr = CprNumber (1, 1, 1, 1118)

If you're outside the Cpr module that defines the type, this doesn't compile. This is by design, but obviously you need a way to create values. For convenience, input values for day, month, and so on, are represented as ints, which can be zero, negative, or way too large for CPR numbers. There's no way to statically guarantee that you can create a value, so you'll have to settle for a tryCreate function; i.e. a function that returns Some CprNumber if the input is valid, or None if it isn't. In Haskell, this pattern is called a smart constructor.

There's a couple of rules to check. All integer values must fall in certain ranges. Days must be between 1 and 31, months must be between 1 and 12, and so on. One way to enable succinct checks like that is with an active pattern:

let private (|Between|_|) min max candidate = if min <= candidate && candidate <= max then Some candidate else None

Straightforward: return Some candidate if candidate is between min and max; otherwise, None. This enables you to pattern-match input integer values to particular ranges.

Perhaps you've already noticed that years are represented with only two digits. CPR is an old system (from 1968), and back then, bits were expensive. No reason to waste bits on recording the millennium or century in which people were born. It turns out, after all, that there's a way to at least partially figure out the century in which people were born. The first digit of the sequence number contains that information:

// int -> int -> int let private calculateFourDigitYear year sequenceNumber = let centuryDigit = sequenceNumber / 1000 // Integer division // Table from https://da.wikipedia.org/wiki/CPR-nummer match centuryDigit, year with | Between 0 3 _, _ -> 1900 | 4 , Between 0 36 _ -> 2000 | 4 , _ -> 1900 | Between 5 8 _, Between 0 57 _ -> 2000 | Between 5 8 _, _ -> 1800 | _ , Between 0 36 _ -> 2000 | _ -> 1900 + year

As the code comment informs the reader, there's a table that defines the century, based on the two-digit year and the first digit of the sequence number. Note that birth dates in the nineteenth century are possible. No Danes born before 1900 are alive any longer, but at the time the CPR system was introduced, one person in the system was born in 1863!

The calculateFourDigitYear function starts by pulling the first digit out of the sequence number. This is a four-digit number, so dividing by 1,000 produces the digit. I left a comment about integer division, because I often miss that detail when I read code.

The big pattern-match expression uses the Between active pattern, but it ignores the return value from the pattern. This explains the wild cards (_), I hope.

Although a pattern-match expression is often formatted over several lines of code, it's a single expression that produces a single value. Often, you see code where a let-binding binds a named value to a pattern-match expression. Another occasional idiom is to pipe a pattern-match expression to a function. In the calculateFourDigitYear function I use a language construct I've never seen anywhere else: the eight-lines pattern-match expression returns an int, which I simply add to year using the + operator.

Both calculateFourDigitYear and the Between active pattern are private functions. They're only there as support functions for the public API. You can now implement a tryCreate function:

// int -> int -> int -> int -> CprNumber option let tryCreate day month year sequenceNumber = match month, year, sequenceNumber with | Between 1 12 m, Between 0 99 y, Between 0 9999 s -> let fourDigitYear = calculateFourDigitYear y s if 1 <= day && day <= DateTime.DaysInMonth (fourDigitYear, m) then Some (CprNumber (day, m, y, s)) else None | _ -> None

The tryCreate function begins by pattern-matching a triple (3-tuple) using the Between active pattern. The month must always be between 1 and 12 (both included), the year must be between 0 and 99, and the sequenceNumber must always be between 0 and 9999 (in fact, I'm not completely sure if 0000 is valid).

Finding the appropriate range for the day is more intricate. Is 31 always valid? Clearly not, because there's no November 31, for example. Is 30 always valid? No, because there's never a February 30. Is 29 valid? This depends on whether or not the year is a leap year.

This reveals why you need calculateFourDigitYear. While you can use DateTime.DaysInMonth to figure out how many days a given month has, you need the year. Specifically, February 1900 had 28 days, while February 2000 had 29.

Ergo, if day, month, year, and sequenceNumber all fall within their appropriate ranges, tryCreate returns a Some CprNumber value; otherwise, it returns None.

Notice how this is different from an object-oriented constructor with guard clauses. If you try to create an object with invalid input, it'll throw an exception. If you try to create a CprNumber value, you'll receive a CprNumber option, and you, as the client developer, must handle both the Some and the None case. The compiler will enforce this.

> let gjern = Cpr.tryCreate 11 11 11 1118;; val gjern : Cpr.CprNumber option = Some 111111-1118 > gjern |> Option.map Cpr.born;; val it : DateTime option = Some 11.11.1911 00:00:00

As most F# developers know, F# gives you enough syntactic sugar to make this a joy rather than a chore... and the warm and fuzzy feeling of safety is priceless.

CPR data #

The above FSI session uses Cpr.born, which you haven't seen yet. With the tools available so far, it's trivial to implement; all the work is already done:

// CprNumber -> DateTime let born (CprNumber (day, month, year, sequenceNumber)) = DateTime (calculateFourDigitYear year sequenceNumber, month, day)

While the CprNumber case constructor is private, it's still available from inside of the module. The born function pattern-matches day, month, year, and sequenceNumber out of its input argument, and trivially delegates the hard work to calculateFourDigitYear.

Another piece of data you can deduce from a CPR number is the gender of the person:

// CprNumber -> bool let isFemale (CprNumber (_, _, _, sequenceNumber)) = sequenceNumber % 2 = 0 let isMale (CprNumber (_, _, _, sequenceNumber)) = sequenceNumber % 2 <> 0

The rule is that if the sequence number is even, then the person is female; otherwise, the person is male (and if you change sex, you get a new CPR number).

> gjern |> Option.map Cpr.isFemale;; val it : bool option = Some true

Since 1118 is even, this is a woman.

Parsing CPR strings #

CPR numbers are often passed around as text, so you'll need to be able to parse a string representation. As described in the previous article, you should follow Postel's law. Input could include extra white space, and the middle dash could be missing.

The .NET Base Class Library contains enough utility methods working on string values that this isn't going to be particularly difficult. It can, however, be awkward to interoperate with object-oriented APIs, so you'll often benefit from adding a few utility functions that give you curried functions instead of objects with methods. Here's one that adapts Int32.TryParse:

module private Int = // string -> int option let tryParse candidate = match candidate |> Int32.TryParse with | true, i -> Some i | _ -> None

Nothing much goes on here. While F# has pleasant syntax for handling out parameters, it can be inconvenient to have to pattern-match every time you'd like to try to parse an integer.

Here's another helper function:

module private String = // int -> int -> string -> string option let trySubstring startIndex length (s : string) = if s.Length < startIndex + length then None else Some (s.Substring (startIndex, length))

This one comes with two benefits: The first benefit is that it's curried, which enables partial application and piping. You'll see an example of this further down. The second benefit is that it handles at least one error condition in a type-safe manner. When trying to extract a sub-string from a string, the Substring method can throw an exception if the index or length arguments are out of range. This function checks whether it can extract the requested sub-string, and returns None if it can't.

I wouldn't be surprised if there are edge cases (for example involving negative integers) that trySubstring doesn't handle gracefully, but as you may have noticed, this is a function in a private module. I only need it to handle a particular use case, and it does that.

You can now add the tryParse function:

// string -> CprNumber option let tryParse (candidate : string ) = let (<*>) fo xo = fo |> Option.bind (fun f -> xo |> Option.map f) let canonicalized = candidate.Trim().Replace("-", "") let dayCandidate = canonicalized |> String.trySubstring 0 2 let monthCandidate = canonicalized |> String.trySubstring 2 2 let yearCandidate = canonicalized |> String.trySubstring 4 2 let sequenceNumberCandidate = canonicalized |> String.trySubstring 6 4 Some tryCreate <*> Option.bind Int.tryParse dayCandidate <*> Option.bind Int.tryParse monthCandidate <*> Option.bind Int.tryParse yearCandidate <*> Option.bind Int.tryParse sequenceNumberCandidate |> Option.bind id

The function starts by defining a private <*> operator. Readers of the applicative functor article series will recognise this as the 'apply' operator. The reason I added it as a private operator is that I don't need it anywhere else in the code base, and in F#, I'm always worried that if I add <*> at a more visible level, it could collide with other definitions of <*> - for example one for lists. This one particularly makes option an applicative functor.

The first step in parsing candidate is to remove surrounding white space and the interior dash.

The next step is to use String.trySubstring to pull out candidates for day, month, and so on. Each of these four are string option values.

All four of these must be Some values before we can even start to attempt to turn them into a CprNumber value. If only a single value is None, tryParse should return None as well.

You may want to re-read the article on the List applicative functor for a detailed explanation of how the <*> operator works. In tryParse, you have four option values, so you apply them all using four <*> operators. Since four values are being applied, you'll need a function that takes four curried input arguments of the appropriate types. In this case, all four are int option values, so for the first expression in the <*> chain, you'll need an option of a function that takes four int arguments.

Lo and behold! tryCreate takes four int arguments, so the only action you need to take is to make it an option by putting it in a Some case.

The only remaining hurdle is that tryCreate returns CprNumber option, and since you're already 'in' the option applicative functor, you now have a CprNumber option option. Fortunately, bind id is always the 'flattening' combo, so that's easily dealt with.

> let andreas = Cpr.tryParse " 0109636221";; val andreas : Cpr.CprNumber option = Some 010963-6221

Since you now have both a way to parse a string, and turn a CprNumber into a string, you can write the usual round-trip property:

[<Fact>] let ``CprNumber correctly round-trips`` () = Property.check <| property { let! expected = Gen.cprNumber let actual = expected |> string |> Cpr.tryParse Some expected =! actual }

This test uses Hedgehog, Unquote, and xUnit.net. The previous article demonstrates a way to test that Cpr.tryParse can handle mangled input.

Summary #

This article mostly exhibited various F# design techniques you can use to achieve an even better degree of encapsulation than you can easily get with object-oriented languages. Towards the end, you saw how using option as an applicative functor enables you to compose more complex optional values from smaller values. If just a single value is None, the entire expression becomes None, but if all values are Some values, the computation succeeds.

This article is an entry in the F# Advent Calendar in English 2018.

Next: The Lazy applicative functor.

Comments

Great post, a very good read! Interestingly enough we recently made an F# implementation for the swedish personal identification number. In fact v1.0.0 will be published any day now. Interesting to see how the problem with four-digit years are handled differently in Denmark and Sweden.

I really like the Between Active pattern of your solution, we did not really take as a generic approach, instead we modeled with types for Year, Month, Day, etc. But I find your solution to be very concise and clear. Also we worked with the Result type instead of Option to be able to provide the client with helpful error messages. For our Object Oriented friends we are also exposing a C#-friendly facade which adds a bit of boiler plate code.

Viktor, thank you for your kind words. The Result (or Either) type does, indeed, provide more information when things go wrong. This can be useful when client code needs to handle different error cases in different ways. Sometimes, it may also be useful, as you write, when you want to provide more helpful error messages.

Particularly when it comes to parsing or input validation, Either can be useful.

The main reason I chose to model with option in this article was that I wanted to demonstrate how to use the applicative nature of option, but I suppose I could have equally done so with Result.

Set is not a functor

Sets aren't functors. An example for object-oriented programmers.

This article is an instalment in an article series about functors. The way functors are frequently presented to programmers is as a generic container (Foo<T>) equipped with a translation method, normally called map, but in C# idiomatically called Select.

It'd be tempting to believe that any generic type with a Select method is a functor, but it takes more than that. The Select method must also obey the functor laws. This article shows an example of a translation that violates the second functor law.

Mapping sets #

The .NET Base Class Library comes with a class called HashSet<T>. This generic class implements IEnumerable<T>, so, via extension methods, it has a Select method.

Unfortunately, that Select method isn't a structure-preserving translation of sets. The problem is that it treats sets as enumerable sequences, which implies an order to elements that isn't part of a set's structure.

In order to understand what the problem is, consider this xUnit.net test:

[Fact] public void SetAsEnumerableSelectLeadsToWrongConclusions() { var set1 = new HashSet<int> { 1, 2, 3 }; var set2 = new HashSet<int> { 3, 2, 1 }; Assert.True(set1.SetEquals(set2)); Func<int, int> id = x => x; var seq1 = set1.AsEnumerable().Select(id); var seq2 = set2.AsEnumerable().Select(id); Assert.False(seq1.SequenceEqual(seq2)); }

This test creates two sets, and by using a Guard Assertion demonstrates that they're equal to each other. It then proceeds to Select over both sets, using the identity function id. The return values aren't HashSet<T> objects, but rather IEnumerable<T> sequences. Due to an implementation detail in HashSet<T>, these two sequences are different, because they were populated in reverse order of each other.

The problem is that the Select extension method has the signature IEnumerable<TResult> Select<T, TResult>(IEnumerable<T>, Func<T, TResult>). It doesn't operate on HashSet<T>, but instead treats it as an ordered sequence of elements. A set isn't intrinsically ordered, so that's not the translation you need.

To be clear, IEnumerable<T> is a functor (as long as the sequence is referentially transparent). It's just not the functor you're looking for. What you need is a method with the signature HashSet<TResult> Select<T, TResult>(HashSet<T>, Func<T, TResult>). Fortunately, such a method is trivial to implement:

public static HashSet<TResult> Select<T, TResult>( this HashSet<T> source, Func<T, TResult> selector) { return new HashSet<TResult>(source.AsEnumerable().Select(selector)); }

This extension method offers a proper Select method that translates one HashSet<T> into another. It does so by enumerating the elements of the set, then using the Select method for IEnumerable<T>, and finally wrapping the resulting sequence in a new HashSet<TResult> object.

This is a better candidate for a translation of sets. Is it a functor, then?

Second functor law #

Even though HashSet<T> and the new Select method have the correct types, it's still only a functor if it obeys the functor laws. It's easy, however, to come up with a counter-example that demonstrates that Select violates the second functor law.

Consider a pair of conversion methods between string and DateTimeOffset:

public static DateTimeOffset ParseDateTime(string s) { DateTimeOffset dt; if (DateTimeOffset.TryParse(s, out dt)) return dt; return DateTimeOffset.MinValue; } public static string FormatDateTime(DateTimeOffset dt) { return dt.ToString("yyyy'-'MM'-'dd'T'HH':'mm':'sszzz"); }

The first method, ParseDateTime, converts a string into a DateTimeOffset value. It tries to parse the input, and returns the corresponding DateTimeOffset value if this is possible; for all other input values, it simply returns DateTimeOffset.MinValue. You may dislike how the method deals with input values it can't parse, but that's not important. In order to prove that sets aren't functors, I just need one counter-example, and the one I'll pick will not involve unparseable strings.

The FormatDateTime method converts any DateTimeOffset value to an ISO 8601 string.

The DateTimeOffset type is the interesting piece of the puzzle. In case you're not intimately familiar with it, a DateTimeOffset value contains a date, a time, and a time-zone offset. You can, for example create one like this:

> new DateTimeOffset(2018, 4, 17, 15, 9, 55, TimeSpan.FromHours(2)) [17.04.2018 15:09:55 +02:00]

This represents April 17, 2018, at 15:09:55 at UTC+2. You can convert that value to UTC:

> new DateTimeOffset(2018, 4, 17, 15, 9, 55, TimeSpan.FromHours(2)).ToUniversalTime() [17.04.2018 13:09:55 +00:00]

This value clearly contains different constituent elements, but it does represent the same instant in time. This is how DateTimeOffset implements Equals. These two object are considered equal, as the following test will demonstrate.

In a sense, you could argue that there's some sense in implementing equality for DateTimeOffset in that way, but this unusual behaviour provides just the counter-example that demonstrates that sets aren't functors:

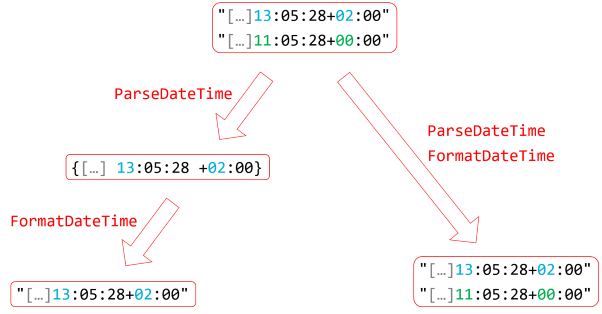

[Fact] public void SetViolatesSecondFunctorLaw() { var x = "2018-04-17T13:05:28+02:00"; var y = "2018-04-17T11:05:28+00:00"; Assert.Equal(ParseDateTime(x), ParseDateTime(y)); var set = new HashSet<string> { x, y }; var l = set.Select(ParseDateTime).Select(FormatDateTime); var r = set.Select(s => FormatDateTime(ParseDateTime(s))); Assert.False(l.SetEquals(r)); }

This passing test provides the required counter-example. It first creates two ISO 8601 representations of the same instant. As the Guard Assertion demonstrates, the corresponding DateTimeOffset values are considered equal.

In the act phase, the test creates a set of these two strings. It then performs two round-trips over DateTimeOffset and back to string. The second functor law states that it shouldn't matter whether you do it in one or two steps, but it does. Assert.False passes because l is not equal to r. Q.E.D.

An illustration #

The problem is that sets only contain one element of each value, and due to the way that DateTimeOffset interprets equality, two values that both represent the same instant are collapsed into a single element when taking an intermediary step. You can illustrate it like this:

In this illustration, I've hidden the date behind an ellipsis in order to improve clarity. The date segments are irrelevant in this example, since they're all identical.

You start with a set of two string values. These are obviously different, so the set contains two elements. When you map the set using the ParseDateTime function, you get two DateTimeOffset values that .NET considers equal. For that reason, HashSet<DateTimeOffset> considers the second value redundant, and ignores it. Therefore, the intermediary set contains only a single element. When you map that set with FormatDateTime, there's only a single element to translate, so the final set contains only a single string value.

On the other hand, when you map the input set without an intermediary set, each string value is first converted into a DateTimeOffset value, and then immediately thereafter converted back to a string value. Since the two resulting strings are different, the resulting set contains two values.

Which of these paths is correct, then? Both of them. That's the problem. When considering the semantics of sets, both translations produce correct results. Since the results diverge, however, the translation isn't a functor.

Summary #

A functor must not only preserve the structure of the data container, but also of functions. The functor laws express that a translation of functions preserves the structure of how the functions compose, in addition to preserving the structure of the containers. Mapping a set doesn't preserve those structures, and that's the reason that sets aren't functors.

P.S. #

2019-01-09. There's been some controversy around this post, and more than one person has pointed out to me that the underlying reason that the functor laws are violated in the above example is because DateTimeOffset behaves oddly. Specifically, its Equals implementation breaks the substitution property of equality. See e.g. Giacomo Citi's response for details.

The term functor originates from category theory, and I don't claim to be an expert on that topic. It's unclear to me if the underlying concept of equality is explicitly defined in category theory, but it wouldn't surprise me if it is. If that definition involves the substitution property, then the counter-example presented here says nothing about Set as a functor, but rather that DateTimeOffset has unlawful equality behaviour.

Next: Applicative functors.

Comments

The Problem here is not the HashSet, but the DateTimeOffset Class. It defines Equality loosely, so Time-Comparison is possible between different Time-Zones. The Functor Property can be restored by applying a stricter Equality Comparer like this one:

var l = set.Select(ParseDateTime, StrictDateTimeOffsetComparer._).Select(FormatDateTime);

/// <summary> Compares both <see cref="DateTimeOffset.Offset"/> and <see cref="DateTimeOffset.UtcTicks"/> </summary>

public class StrictDateTimeOffsetComparer : IEqualityComparer<DateTimeOffset> {

public bool Equals(DateTimeOffset x, DateTimeOffset y)

=> x.Offset.Equals(y.Offset) && x.UtcTicks == y.UtcTicks;

public int GetHashCode(DateTimeOffset obj) => HashCode.Combine(obj.Offset, obj.UtcTicks);

/// <summary> Singleton Instance </summary>

public static readonly StrictDateTimeOffsetComparer _ = new();

StrictDateTimeOffsetComparer(){}

}

As for preserving Referential Transparency, the Distinction between Equality and Identity is important.

By Default, Classes implement 'Equals' and '==' using ReferenceEquals which guarantees Substitution.

Structs don't have a Reference unless they are boxed, instead they are copied and usually have Value Semantics.

To be truly 'referentially transparent' though, Equality must be based on ALL Fields.

When someone overrides Equals with a weaker Equivalence Relation than ReferenceEquals,

it is their Responsibility to preserve Substitution.

No Library Author can cover all possible application cases for HashSet.