ploeh blog danish software design

The Equivalence contravariant functor

An introduction to the Equivalence contravariant functor for object-oriented programmers.

This article is an instalment in an article series about contravariant functors. It assumes that you've read the introduction. In previous articles, you saw examples of the Command Handler and Specification contravariant functors. This article presents another example.

In a recent article I described how I experimented with removing the id property from a JSON representation in a REST API. I also mentioned that doing that made one test fail. In this article you'll see the failing test and how the Equivalence contravariant functor can improve the situation.

Baseline #

Before I made the change, the test in question looked like this:

[Theory] [InlineData(1049, 19, 00, "juliad@example.net", "Julia Domna", 5)] [InlineData(1130, 18, 15, "x@example.com", "Xenia Ng", 9)] [InlineData( 956, 16, 55, "kite@example.edu", null, 2)] [InlineData( 433, 17, 30, "shli@example.org", "Shanghai Li", 5)] public async Task PostValidReservationWhenDatabaseIsEmpty( int days, int hours, int minutes, string email, string name, int quantity) { var at = DateTime.Now.Date + new TimeSpan(days, hours, minutes, 0); var db = new FakeDatabase(); var sut = new ReservationsController( new SystemClock(), new InMemoryRestaurantDatabase(Grandfather.Restaurant), db); var dto = new ReservationDto { Id = "B50DF5B1-F484-4D99-88F9-1915087AF568", At = at.ToString("O"), Email = email, Name = name, Quantity = quantity }; await sut.Post(dto); var expected = new Reservation( Guid.Parse(dto.Id), at, new Email(email), new Name(name ?? ""), quantity); Assert.Contains(expected, db.Grandfather); }

You can find this test in the code base that accompanies my book Code That Fits in Your Head, although I've slightly simplified the initialisation of expected since I froze the code for the manuscript. I've already discussed this particular test in the articles Branching tests, Waiting to happen, and Parametrised test primitive obsession code smell. It's the gift that keeps giving.

It's a state-based integration test that verifies the state of the FakeDatabase after 'posting' a reservation to 'the REST API'. I'm using quotes because the test doesn't really perform an HTTP POST request (it's not a self-hosted integration test). Rather, it directly calls the Post method on the sut. In the assertion phase, it uses Back Door Manipulation (as xUnit Test Patterns terms it) to verify the state of the Fake db.

If you're wondering about the Grandfather property, it represents the original restaurant that was grandfathered in when I expanded the REST API to a multi-tenant service.

Notice, particularly, the use of dto.Id when defining the expected reservation.

Brittle assertion #

When I made the Id property internal, this test no longer compiled. I had to delete the assignment of Id, which also meant that I couldn't use a deterministic Guid to define the expected value. While I could create an arbitrary Guid, that would never pass the test, since the Post method also generates a new Guid.

In order to get to green as quickly as possible, I rewrote the assertion:

Assert.Contains( db.Grandfather, r => DateTime.Parse(dto.At, CultureInfo.InvariantCulture) == r.At && new Email(dto.Email) == r.Email && new Name(dto.Name ?? "") == r.Name && dto.Quantity == r.Quantity);

This passed the test so that I could move on. It may even be the simplest thing that could possibly work, but it's brittle and noisy.

It's brittle because it explicitly considers the four properties At, Email, Name, and Quantity of the Reservation class. What happens if you add a new property to Reservation? What happens if you have similar assertions scattered over the code base?

This is one reason that DRY also applies to unit tests. You want to have as few places as possible that you have to edit when making changes. Otherwise, the risk increases that you forget one or more.

Not only is the assertion brittle - it's also noisy, because it's hard to read. There's parsing, null coalescing and object initialisation going on in those four lines of Boolean operations. Perhaps it'd be better to extract a well-named helper method, but while I'm often in favour of doing that, I'm also a little concerned that too many ad-hoc helper methods obscure something essential. After all:

"Abstraction is the elimination of the irrelevant and the amplification of the essential"

The hardest part of abstraction is striking the right balance. Does a well-named helper method effectively communicate the essentials while eliminating only the irrelevant. While I favour good names over bad names, I'm also aware that good names are skin-deep. If I can draw on a universal abstraction rather than coming up with an ad-hoc name, I prefer doing that.

Which universal abstraction might be useful in this situation?

Relaxed comparison #

The baseline version of the test relied on the structural equality of the Reservation class:

public override bool Equals(object? obj) { return obj is Reservation reservation && Id.Equals(reservation.Id) && At == reservation.At && EqualityComparer<Email>.Default.Equals(Email, reservation.Email) && EqualityComparer<Name>.Default.Equals(Name, reservation.Name) && Quantity == reservation.Quantity; }

This implementation was auto-generated by a Visual Studio Quick Action. From C# 9, I could also have made Reservation a record, in which case the compiler would be taking care of implementing Equals.

The Reservation class already defines the canonical way to compare two reservations for equality. Why can't we use that?

The PostValidReservationWhenDatabaseIsEmpty test can no longer use the Reservation class' structural equality because it doesn't know what the Id is going to be.

One way to address this problem is to inject a hypothetical IGuidGenerator dependency into ReservationsController. I consider this a valid alternative, since the Controller already takes an IClock dependency. I might be inclined towards such a course of action for other reasons, but here I wanted to explore other options.

Can we somehow reuse the Equals implementation of Reservation, but relax its behaviour so that it doesn't consider the Id?

This would be what Ted Neward called negative variability - the ability to subtract from an existing feature. As he implied in 2010, normal programming languages don't have that capability. That strikes me as true in 2021 as well.

The best we can hope for, then, is to put the required custom comparison somewhere central, so that at least it's not scattered across the entire code base. Since the test uses xUnit.net, a class that implements IEqualityComparer<Reservation> sounds like just the right solution.

This is definitely doable, but it's odd having to define a custom equality comparer for a class that already has structural equality. In the context of the PostValidReservationWhenDatabaseIsEmpty test, we understand the reason, but for a future team member who may encounter the class out of context, it might be confusing.

Are there other options?

Reuse #

It turns out that, by lucky accident, the code base already contains an equality comparer that almost fits:

internal sealed class ReservationDtoComparer : IEqualityComparer<ReservationDto> { public bool Equals(ReservationDto? x, ReservationDto? y) { var datesAreEqual = Equals(x?.At, y?.At); if (!datesAreEqual && DateTime.TryParse(x?.At, out var xDate) && DateTime.TryParse(y?.At, out var yDate)) datesAreEqual = Equals(xDate, yDate); return datesAreEqual && Equals(x?.Email, y?.Email) && Equals(x?.Name, y?.Name) && Equals(x?.Quantity, y?.Quantity); } public int GetHashCode(ReservationDto obj) { var dateHash = obj.At?.GetHashCode(StringComparison.InvariantCulture); if (DateTime.TryParse(obj.At, out var dt)) dateHash = dt.GetHashCode(); return HashCode.Combine(dateHash, obj.Email, obj.Name, obj.Quantity); } }

This class already compares two reservations' dates, emails, names, and quantities, while ignoring any IDs. Just what we need?

There's only one problem. ReservationDtoComparer compares ReservationDto objects - not Reservation objects.

Would it be possible to somehow, on the spot, without writing a new class, transform ReservationDtoComparer to an IEqualityComparer<Reservation>?

Well, yes it is.

Contravariant functor #

We can contramap an IEqualityComparer<ReservationDto> to a IEqualityComparer<Reservation> because equivalence gives rise to a contravariant functor.

In order to enable contravariant mapping, you must add a ContraMap method:

public static class Equivalance { public static IEqualityComparer<T1> ContraMap<T, T1>( this IEqualityComparer<T> source, Func<T1, T> selector) where T : notnull { return new ContraMapComparer<T, T1>(source, selector); } private sealed class ContraMapComparer<T, T1> : IEqualityComparer<T1> where T : notnull { private readonly IEqualityComparer<T> source; private readonly Func<T1, T> selector; public ContraMapComparer(IEqualityComparer<T> source, Func<T1, T> selector) { this.source = source; this.selector = selector; } public bool Equals([AllowNull] T1 x, [AllowNull] T1 y) { if (x is null && y is null) return true; if (x is null || y is null) return false; return source.Equals(selector(x), selector(y)); } public int GetHashCode(T1 obj) { return source.GetHashCode(selector(obj)); } } }

Since the IEqualityComparer<T> interface defines two methods, the selector must contramap the behaviour of both Equals and GetHashCode. Fortunately, that's possible.

Notice that, as explained in the overview article, in order to map from an IEqualityComparer<T> to an IEqualityComparer<T1>, the selector has to go the other way: from T1 to T. How this is possible will become more apparent with an example, which will follow later in the article.

Identity law #

A ContraMap method with the right signature isn't enough to be a contravariant functor. It must also obey the contravariant functor laws. As usual, it's proper computer-science work to actually prove this, but you can write some tests to demonstrate the identity law for the IEqualityComparer<T> interface. In this article, you'll see parametrised tests written with xUnit.net. First, the identity law:

[Theory] [InlineData("18:30", 1, "18:30", 1)] [InlineData("18:30", 2, "18:30", 2)] [InlineData("19:00", 1, "19:00", 1)] [InlineData("18:30", 1, "19:00", 1)] [InlineData("18:30", 2, "18:30", 1)] public void IdentityLaw(string time1, int size1, string time2, int size2) { var sut = new TimeDtoComparer(); T id<T>(T x) => x; IEqualityComparer<TimeDto>? actual = sut.ContraMap<TimeDto, TimeDto>(id); var dto1 = new TimeDto { Time = time1, MaximumPartySize = size1 }; var dto2 = new TimeDto { Time = time2, MaximumPartySize = size2 }; Assert.Equal(sut.Equals(dto1, dto2), actual.Equals(dto1, dto2)); Assert.Equal(sut.GetHashCode(dto1), actual.GetHashCode(dto1)); }

In order to observe that the two comparers have identical behaviours, the test must invoke both the Equals and the GetHashCode methods on both sut and actual to assert that the two different objects produce the same output.

All test cases pass.

Composition law #

Like the above example, you can also write a parametrised test that demonstrates that ContraMap obeys the composition law for contravariant functors:

[Theory] [InlineData(" 7:45", "18:13")] [InlineData("18:13", "18:13")] [InlineData("22" , "22" )] [InlineData("22:32", "22" )] [InlineData( "9" , "9" )] [InlineData( "9" , "8" )] public void CompositionLaw(string time1, string time2) { IEqualityComparer<TimeDto> sut = new TimeDtoComparer(); Func<string, (string, int)> f = s => (s, s.Length); Func<(string s, int i), TimeDto> g = t => new TimeDto { Time = t.s, MaximumPartySize = t.i }; IEqualityComparer<string>? projection1 = sut.ContraMap((string s) => g(f(s))); IEqualityComparer<string>? projection2 = sut.ContraMap(g).ContraMap(f); Assert.Equal( projection1.Equals(time1, time2), projection2.Equals(time1, time2)); Assert.Equal( projection1.GetHashCode(time1), projection2.GetHashCode(time1)); }

This test defines two local functions, f and g. Once more, you can't directly compare methods for equality, so instead you have to call both Equals and GetHashCode on projection1 and projection2 to verify that they return the same values.

They do.

Relaxed assertion #

The code base already contains a function that converts Reservation values to ReservationDto objects:

public static ReservationDto ToDto(this Reservation reservation) { if (reservation is null) throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(reservation)); return new ReservationDto { Id = reservation.Id.ToString("N"), At = reservation.At.ToIso8601DateTimeString(), Email = reservation.Email.ToString(), Name = reservation.Name.ToString(), Quantity = reservation.Quantity }; }

Given that it's possible to map from Reservation to ReservationDto, it's also possible to map equality comparers in the contrary direction: from IEqualityComparer<ReservationDto> to IEqualityComparer<Reservation>. That's just what the PostValidReservationWhenDatabaseIsEmpty test needs!

Most of the test stays the same, but you can now write the assertion as:

var expected = new Reservation( Guid.NewGuid(), at, new Email(email), new Name(name ?? ""), quantity); Assert.Contains( expected, db.Grandfather, new ReservationDtoComparer().ContraMap((Reservation r) => r.ToDto()));

Instead of using the too-strict equality comparison of Reservation, the assertion now takes advantage of the relaxed, test-specific comparison of ReservationDto objects.

What's not to like?

To be truthful, this probably isn't a trick I'll perform often. I think it's fair to consider contravariant functors an advanced programming concept. On a team, I'd be concerned that colleagues wouldn't understand what's going on here.

The purpose of this article series isn't to advocate for this style of programming. It's to show some realistic examples of contravariant functors.

Even in Haskell, where contravariant functors are en explicit part of the base package, I can't recall having availed myself of this functionality.

Equivalence in Haskell #

The Haskell Data.Functor.Contravariant module defines a Contravariant type class and some instances to go with it. One of these is a newtype called Equivalence, which is just a wrapper around a -> a -> Bool.

In Haskell, equality is normally defined by the Eq type class. You can trivially 'promote' any Eq instance to an Equivalence instance using the defaultEquivalence value.

To illustrate how this works in Haskell, you can reproduce the two reservation types:

data Reservation = Reservation { reservationID :: UUID, reservationAt :: LocalTime, reservationEmail :: String, reservationName :: String, reservationQuantity :: Int } deriving (Eq, Show) data ReservationJson = ReservationJson { jsonAt :: String, jsonEmail :: String, jsonName :: String, jsonQuantity :: Double } deriving (Eq, Show, Read, Generic)

The ReservationJson type doesn't have an ID, whereas Reservation does. Still, you can easily convert from Reservation to ReservationJson:

reservationToJson :: Reservation -> ReservationJson reservationToJson (Reservation _ at email name q) = ReservationJson (show at) email name (fromIntegral q)

Now imagine that you have two reservations that differ only on reservationID:

reservation1 :: Reservation reservation1 = Reservation (fromWords 3822151499 288494060 2147588346 2611157519) (LocalTime (fromGregorian 2021 11 11) (TimeOfDay 12 30 0)) "just.inhale@example.net" "Justin Hale" 2 reservation2 :: Reservation reservation2 = Reservation (fromWords 1263859666 288625132 2147588346 2611157519) (LocalTime (fromGregorian 2021 11 11) (TimeOfDay 12 30 0)) "just.inhale@example.net" "Justin Hale" 2

If you compare these two values using the standard equality operator, they're (not surprisingly) not the same:

> reservation1 == reservation2 False

Attempting to compare them using the default Equivalence value doesn't help, either:

> (getEquivalence $ defaultEquivalence) reservation1 reservation2 False

But if you promote the comparison to Equivalence and then contramap it with reservationToJson, they do look the same:

> (getEquivalence $ contramap reservationToJson $ defaultEquivalence) reservation1 reservation2 True

This Haskell example is equivalent in spirit to the above C# assertion.

Notice that Equivalence is only a wrapper around any function of the type a -> a -> Bool. This corresponds to the IEqualityComparer interface's Equals method. On the other hand, Equivalence has no counterpart to GetHashCode - that's a .NETism.

When using Haskell as inspiration for identifying universal abstractions, it's not entirely clear how Equivalence is similar to IEqualityComparer<T>. While a -> a -> Bool is isomorphic to its Equals method, and thus gives rise to a contravariant functor, what about the GetHashCode method?

As this article has demonstrated, it turned out that it's possible to also contramap the GetHashCode method, but was that just a fortunate accident, or is there something more fundamental going on?

Conclusion #

Equivalence relations give rise to a contravariant functor. In this article, you saw how this property can be used to relax assertions in unit tests.

Strictly speaking, an equivalence relation is exclusively a function that compares two values to return a Boolean value. No GetHashCode method is required. That's a .NET-specific implementation detail that, unfortunately, has been allowed to leak into the object base class. It's not part of the concept of an equivalence relation, but still, it's possible to form a contravariant functor from IEqualityComparer<T>. Is this just a happy coincidence, or could there be something more fundamental going on?

Read on.

Keep IDs internal with REST

Instead of relying on entity IDs, use hypermedia to identify resources.

Whenever I've helped teams design HTTP APIs, sooner or later one request comes up - typically from client developers: Please add the entity ID to the representation.

In this article I'll show an alternative, but first: the normal state of affairs.

Business as usual #

It's such a common requirement that, despite admonitions not to expose IDs, I did it myself in the code base that accompanies my book Code That Fits in Your Head. This code base is a level 3 REST API, and still, I'd included the ID in the JSON representation of a reservation:

{

"id": "bf4e84130dac451b9c94049da8ea8c17",

"at": "2021-12-08T20:30:00.0000000",

"email": "snomob@example.com",

"name": "Snow Moe Beal",

"quantity": 1

}

At least the ID is a GUID, so I'm not exposing internal database IDs.

After having written the book, the id property kept nagging me, and I wondered if it'd be possible to get rid of it. After all, in a true REST API, clients aren't supposed to construct URLs from templates. They're supposed to follow links. So why do you need the ID?

Following links #

Early on in the system's lifetime, I began signing all URLs to prevent clients from retro-engineering URLs. This also meant that most of my self-hosted integration tests were already following links:

[Theory] [InlineData(867, 19, 10, "adur@example.net", "Adrienne Ursa", 2)] [InlineData(901, 18, 55, "emol@example.gov", "Emma Olsen", 5)] public async Task ReadSuccessfulReservation( int days, int hours, int minutes, string email, string name, int quantity) { using var api = new LegacyApi(); var at = DateTime.Today.AddDays(days).At(hours, minutes) .ToIso8601DateTimeString(); var expected = Create.ReservationDto(at, email, name, quantity); var postResp = await api.PostReservation(expected); Uri address = FindReservationAddress(postResp); var getResp = await api.CreateClient().GetAsync(address); getResp.EnsureSuccessStatusCode(); var actual = await getResp.ParseJsonContent<ReservationDto>(); Assert.Equal(expected, actual, new ReservationDtoComparer()); AssertUrlFormatIsIdiomatic(address); }

This parametrised test uses xUnit.net 2.4.1 to first post a new reservation to the system, and then following the link provided in the response's Location header to verify that this resource contains a representation compatible with the reservation that was posted.

A corresponding plaintext HTTP session would start like this:

POST /restaurants/90125/reservations?sig=aco7VV%2Bh5sA3RBtrN8zI8Y9kLKGC60Gm3SioZGosXVE%3D HTTP/1.1

Content-Type: application/json

{

"at": "2021-12-08 20:30",

"email": "snomob@example.com",

"name": "Snow Moe Beal",

"quantity": 1

}

HTTP/1.1 201 Created

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

Location: example.com/restaurants/90125/reservations/bf4e84130dac451b9c94049da8ea8c17?sig=ZVM%2[...]

{

"id": "bf4e84130dac451b9c94049da8ea8c17",

"at": "2021-12-08T20:30:00.0000000",

"email": "snomob@example.com",

"name": "Snow Moe Beal",

"quantity": 1

}

That's the first request and response. Clients can now examine the response's headers to find the Location header. That URL is the actual, external ID of the resource, not the id property in the JSON representation.

The client can save that URL and request it whenever it needs the reservation:

GET /restaurants/90125/reservations/bf4e84130dac451b9c94049da8ea8c17?sig=ZVM%2[...] HTTP/1.1

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

{

"id": "bf4e84130dac451b9c94049da8ea8c17",

"at": "2021-12-08T20:30:00.0000000",

"email": "snomob@example.com",

"name": "Snow Moe Beal",

"quantity": 1

}

The actual, intended use of the API doesn't rely on the id property, neither do the tests.

Based on this consistent design principle, I had reason to hope that I'd be able to remove the id property.

Breaking change #

My motivation for making this change was to educate myself. I wanted to see if it would be possible to design a REST API that doesn't expose IDs in their JSON (or XML) representations. Usually I'm having trouble doing this in practice because when I'm consulting, I'm typically present to help the organisation with test-driven development and how to organise their code. It's always hard to learn new ways of doing things, and I don't wish to overwhelm my clients with too many changes all at once.

So I usually let them do level 2 APIs because that's what they're comfortable with. With that style of HTTP API design, it's hard to avoid id fields.

This wasn't a constraint for the book's code, so I'd gone full REST on that API, and I'm happy that I did. By habit, though, I'd exposed the id property in JSON, and I now wanted to perform an experiment: Could I remove the field?

A word of warning: You can't just remove a JSON property from a production API. That would constitute a breaking change, and even though clients aren't supposed to use the id, Hyrum's law says that someone somewhere probably already is.

This is just an experiment that I carried out on a separate Git branch, for my own edification.

Leaning on the compiler #

As outlined, I had relatively strong faith in my test suite, so I decided to modify the Data Transfer Object (DTO) in question. Before the change, it looked like this:

public sealed class ReservationDto { public LinkDto[]? Links { get; set; } public string? Id { get; set; } public string? At { get; set; } public string? Email { get; set; } public string? Name { get; set; } public int Quantity { get; set; } }

At first, I simply tried to delete the Id property, but while it turned out to be not too bad in general, it did break one feature: The ability of the LinksFilter to generate links to reservations. Instead, I changed the Id property to be internal:

public sealed class ReservationDto { public LinkDto[]? Links { get; set; } internal string? Id { get; set; } public string? At { get; set; } public string? Email { get; set; } public string? Name { get; set; } public int Quantity { get; set; } }

This enables the LinksFilter and other internal code to still access the Id property, while the unit tests no longer could. As expected, this change caused some compiler errors. That was expected, and my plan was to lean on the compiler, as Michael Feathers describes in Working Effectively with Legacy Code.

As I had hoped, relatively few things broke, and they were fixed in 5-10 minutes. Once everything compiled, I ran the tests. Only a single test failed, and this was a unit test that used some Back Door Manipulation, as xUnit Test Patterns terms it. I'll return to that test in a future article.

None of my self-hosted integration tests failed.

ID-free interaction #

Since clients are supposed to follow links, they can still do so. For example, a maître d'hôtel might request the day's schedule:

GET /restaurants/90125/schedule/2021/12/8?sig=82fosBYsE9zSKkA4Biy5t%2BFMxl71XiLlFKaI2E[...] HTTP/1.1

Authorization: Bearer eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJyZXN0YXVyYW50IjpbIjEiLCIyMTEyIiwi[...]

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

{

"name": "The Vatican Cellar",

"year": 2021,

"month": 12,

"day": 8,

"days": [

{

"date": "2021-12-08",

"entries": [

{

"time": "20:30:00",

"reservations": [

{

"links": [

{

"rel": "urn:reservation",

"href": "http://example.com/restaurants/90125/reservations/bf4e84130dac4[...]"

}

],

"at": "2021-12-08T20:30:00.0000000",

"email": "snomob@example.com",

"name": "Snow Moe Beal",

"quantity": 1

}

]

}

]

}

]

}

I've edited the response quite heavily by removing other links, and so on.

Clients that wish to navigate to Snow Moe Beal's reservation must locate its urn:reservation link and use the corresponding href value. This is an opaque URL that clients can use to make requests:

GET /restaurants/90125/reservations/bf4e84130dac451b9c94049da8ea8c17?sig=vxkBT1g1GHRmx[...] HTTP/1.1

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

{

"at": "2021-12-08T20:30:00.0000000",

"email": "snomob@example.com",

"name": "Snow Moe Beal",

"quantity": 1

}

In none of these interactions do clients rely on the id property - which is also gone now. It's gone because the Id property on the C# DTO is internal, which means that it's not being rendered.

Mission accomplished.

Conclusion #

It always grates on me when I have to add an id property to a representation in an HTTP API. It's often necessary when working with a level 2 API, but with a proper hypermedia-driven REST API, it may not be necessary.

At least, the experiment I performed with the code base from my book Code That Fits in Your Head indicates that this may be so.

Unit testing private helper methods

Evolving a private helper method, guided by tests.

A frequently asked question about unit testing and test-driven development (TDD) is how to test private helper methods. I've already attempted to answer that question: through the public API, but a recent comment to a Stack Overflow question made me realise that I've failed to supply a code example.

Show, don't tell.

In this article I'll show a code example that outlines how a private helper method can evolve under TDD.

Threshold #

The code example in this article comes from my book Code That Fits in Your Head. When you buy the book, you get not only the finished code examples, but the entire Git repository, with detailed commit messages.

A central part of the code base is a method that decides whether or not to accept a reservation attempt. It's essentially a solution to the Maître d' kata. I wrote most of the book's code with TDD, and after commit fa12fd69c158168178f3a75bcd900e5caa7e7dec I decided that I ought to refactor the implementation. As I wrote in the commit message:

Filter later reservations based on date The line count of the willAccept method has now risen to 28. Cyclomatic complexity is still at 7. It's ripe for refactoring.

I think, by the way, that I made a small mistake. As far as I can tell, the WillAccept line count in this commit is 26 - not 28:

public bool WillAccept( IEnumerable<Reservation> existingReservations, Reservation candidate) { if (existingReservations is null) throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(existingReservations)); if (candidate is null) throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(candidate)); var relevantReservations = existingReservations .Where(r => candidate.At.Date == r.At.Date); List<Table> availableTables = Tables.ToList(); foreach (var r in relevantReservations) { var table = availableTables.Find(t => r.Quantity <= t.Seats); if (table is { }) { availableTables.Remove(table); if (table.IsCommunal) availableTables.Add(table.Reserve(r.Quantity)); } } return availableTables.Any(t => candidate.Quantity <= t.Seats); }

Still, I knew that it wasn't done - that I'd be adding more tests that would increase both the size and complexity of the method. It was brushing against more than one threshold. I decided that it was time for a prophylactic refactoring.

Notice that the red-green-refactor checklist explicitly states that refactoring is part of the process. It doesn't, however, mandate that refactoring must be done in the same commit as the green phase. Here, I did red-green-commit-refactor-commit.

While I decided to refactor, I also knew that I still had some way to go before WillAccept would be complete. With the code still in flux, I didn't want to couple tests to a new method, so I chose to extract a private helper method.

Helper method #

After the refactoring, the code looked like this:

public bool WillAccept( IEnumerable<Reservation> existingReservations, Reservation candidate) { if (existingReservations is null) throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(existingReservations)); if (candidate is null) throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(candidate)); var relevantReservations = existingReservations .Where(r => candidate.At.Date == r.At.Date); var availableTables = Allocate(relevantReservations); return availableTables.Any(t => candidate.Quantity <= t.Seats); } private IEnumerable<Table> Allocate( IEnumerable<Reservation> reservations) { List<Table> availableTables = Tables.ToList(); foreach (var r in reservations) { var table = availableTables.Find(t => r.Quantity <= t.Seats); if (table is { }) { availableTables.Remove(table); if (table.IsCommunal) availableTables.Add(table.Reserve(r.Quantity)); } } return availableTables; }

I committed the change, and wrote in the commit message:

Extract helper method from WillAccept This quite improves the complexity of the method, which is now 4, and at 18 lines of code. The new helper method also has a cyclomatic complexity of 4, and 17 lines of code. A remaining issue with the WillAccept method is that the code operates on different levels of abstraction. The call to Allocate represents an abstraction, while the filter on date is as low-level as it can get.

As you can tell, I was well aware that there were remaining issues with the code.

Since the new Allocate helper method is private, unit tests can't reach it directly. It's still covered by tests, though, just as that code block was before I extracted it.

More tests #

I wasn't done with the WillAccept method, and after a bout of other refactorings, I added more test cases covering it.

While the method ultimately grew to exhibit moderately complex behaviour, I had only two test methods covering it: one (not shown) for the rejection case, and another for the accept (true) case:

[Theory, ClassData(typeof(AcceptTestCases))] public void Accept( TimeSpan seatingDuration, IEnumerable<Table> tables, IEnumerable<Reservation> reservations) { var sut = new MaitreD(seatingDuration, tables); var r = Some.Reservation.WithQuantity(11); var actual = sut.WillAccept(reservations, r); Assert.True(actual); }

I based the example code on the impureim sandwich architecture, which meant that domain logic (including the WillAccept method) is all pure functions. The nice thing about pure functions is that they're easy to unit test.

The Accept test method uses an object data source (see the article Parametrised test primitive obsession code smell for another example of the motivation behind using objects for test parametrisation), so adding more test cases were simply a matter of adding them to the data source:

Add(TimeSpan.FromHours(6), new[] { Table.Communal(11) }, new[] { Some.Reservation.WithQuantity(11).TheDayAfter() }); Add(TimeSpan.FromHours(2.5), new[] { Table.Standard(12) }, new[] { Some.Reservation.WithQuantity(11).AddDate( TimeSpan.FromHours(-2.5)) }); Add(TimeSpan.FromHours(1), new[] { Table.Standard(14) }, new[] { Some.Reservation.WithQuantity(9).AddDate( TimeSpan.FromHours(1)) });

The bottom two test cases are new additions. In that way, by adding new test cases, I could keep evolving WillAccept and its various private helper methods (of which I added more). While no tests directly exercise the private helper methods, the unit tests still transitively exercise the private parts of the code base.

Since I followed TDD, no private helper methods sprang into existence untested. I didn't have to jump through hoops in order to be able to unit test private helper methods. Rather, the private helper methods were a natural by-product of the red-green-refactor process - particularly, the refactor phase.

Conclusion #

Following TDD doesn't preclude the creation of private helper methods. In fact, private helper methods can (and should?) emerge during the refactoring phase of the red-green-refactoring cycle.

For long-time practitioners of TDD, there's nothing new in this, but people new to TDD are still learning. This question keeps coming up, so I hope that this example is useful.

The Specification contravariant functor

An introduction for object-oriented programmers to the Specification contravariant functor.

This article is an instalment in an article series about contravariant functors. It assumes that you've read the introduction. In the previous article, you saw an example of a contravariant functor based on the Command Handler pattern. This article gives another example.

Domain-Driven Design discusses the benefits of the Specification pattern. In its generic incarnation this pattern gives rise to a contravariant functor.

Interface #

DDD introduces the pattern with a non-generic InvoiceSpecification interface. The book also shows other examples, and it quickly becomes clear that with generics, you can generalise the pattern to this interface:

public interface ISpecification<T> { bool IsSatisfiedBy(T candidate); }

Given such an interface, you can implement standard reusable Boolean logic such as and, or, and not. (Exercise: consider how implementations of and and or correspond to well-known monoids. Do the implementations look like Composites? Is that a coincidence?)

The ISpecification<T> interface is really just a glorified predicate. These days the Specification pattern may seem somewhat exotic in languages with first-class functions. C#, for example, defines both a specialised Predicate delegate, as well as the more general Func<T, bool> delegate. Since you can pass those around as objects, that's often good enough, and you don't need an ISpecification interface.

Still, for the sake of argument, in this article I'll start with the Specification pattern and demonstrate how that gives rise to a contravariant functor.

Natural number specification #

Consider the AdjustInventoryService class from the previous article. I'll repeat the 'original' Execute method here:

public void Execute(AdjustInventory command) { var productInventory = this.repository.GetByIdOrNull(command.ProductId) ?? new ProductInventory(command.ProductId); int quantityAdjustment = command.Quantity * (command.Decrease ? -1 : 1); productInventory = productInventory.AdjustQuantity(quantityAdjustment); if (productInventory.Quantity < 0) throw new InvalidOperationException("Can't decrease below 0."); this.repository.Save(productInventory); }

Notice the Guard Clause:

if (productInventory.Quantity < 0)

Image that we'd like to introduce some flexibility here. It's admittedly a silly example, but just come along for the edification. Imagine that we'd like to use an injected ISpecification<ProductInventory> instead:

if (!specification.IsSatisfiedBy(productInventory))

That doesn't sound too difficult, but what if you only have an ISpecification implementation like the following?

public sealed class NaturalNumber : ISpecification<int> { public readonly static ISpecification<int> Specification = new NaturalNumber(); private NaturalNumber() { } public bool IsSatisfiedBy(int candidate) { return 0 <= candidate; } }

That's essentially what you need, but alas, it only implements ISpecification<int>, not ISpecification<ProductInventory>. Do you really have to write a new Adapter just to implement the right interface?

No, you don't.

Contravariant functor #

Fortunately, an interface like ISpecification<T> gives rise to a contravariant functor. This will enable you to compose an ISpecification<ProductInventory> object from the NaturalNumber specification.

In order to enable contravariant mapping, you must add a ContraMap method:

public static ISpecification<T1> ContraMap<T, T1>( this ISpecification<T> source, Func<T1, T> selector) { return new ContraSpecification<T, T1>(source, selector); } private class ContraSpecification<T, T1> : ISpecification<T1> { private readonly ISpecification<T> source; private readonly Func<T1, T> selector; public ContraSpecification(ISpecification<T> source, Func<T1, T> selector) { this.source = source; this.selector = selector; } public bool IsSatisfiedBy(T1 candidate) { return source.IsSatisfiedBy(selector(candidate)); } }

Notice that, as explained in the overview article, in order to map from an ISpecification<T> to an ISpecification<T1>, the selector has to go the other way: from T1 to T. How this is possible will become more apparent with an example, which will follow later in the article.

Identity law #

A ContraMap method with the right signature isn't enough to be a contravariant functor. It must also obey the contravariant functor laws. As usual, it's proper computer-science work to actually prove this, but you can write some tests to demonstrate the identity law for the ISpecification<T> interface. In this article, you'll see parametrised tests written with xUnit.net. First, the identity law:

[Theory] [InlineData(-102)] [InlineData( -3)] [InlineData( -1)] [InlineData( 0)] [InlineData( 1)] [InlineData( 32)] [InlineData( 283)] public void IdentityLaw(int input) { T id<T>(T x) => x; ISpecification<int> projection = NaturalNumber.Specification.ContraMap<int, int>(id); Assert.Equal( NaturalNumber.Specification.IsSatisfiedBy(input), projection.IsSatisfiedBy(input)); }

In order to observe that the two Specifications have identical behaviours, the test has to invoke IsSatisfiedBy on both of them to verify that the return values are the same.

All test cases pass.

Composition law #

Like the above example, you can also write a parametrised test that demonstrates that ContraMap obeys the composition law for contravariant functors:

[Theory] [InlineData( "0:05")] [InlineData( "1:20")] [InlineData( "0:12:10")] [InlineData( "1:00:12")] [InlineData("1.13:14:34")] public void CompositionLaw(string input) { Func<string, TimeSpan> f = TimeSpan.Parse; Func<TimeSpan, int> g = ts => (int)ts.TotalMinutes; Assert.Equal( NaturalNumber.Specification.ContraMap((string s) => g(f(s))).IsSatisfiedBy(input), NaturalNumber.Specification.ContraMap(g).ContraMap(f).IsSatisfiedBy(input)); }

This test defines two local functions, f and g. Once more, you can't directly compare methods for equality, so instead you have to call IsSatisfiedBy on both compositions to verify that they return the same Boolean value.

They do.

Product inventory specification #

You can now produce the desired ISpecification<ProductInventory> from the NaturalNumber Specification without having to add a new class:

ISpecification<ProductInventory> specification = NaturalNumber.Specification.ContraMap((ProductInventory inv) => inv.Quantity);

Granted, it is, once more, a silly example, but the purpose of this article isn't to convince you that this is better (it probably isn't). The purpose of the article is to show an example of a contravariant functor, and how it can be used.

Predicates #

For good measure, any predicate forms a contravariant functor. You don't need the ISpecification interface. Here are ContraMap overloads for Predicate<T> and Func<T, bool>:

public static Predicate<T1> ContraMap<T, T1>(this Predicate<T> predicate, Func<T1, T> selector) { return x => predicate(selector(x)); } public static Func<T1, bool> ContraMap<T, T1>(this Func<T, bool> predicate, Func<T1, T> selector) { return x => predicate(selector(x)); }

Notice that the lambda expressions are identical in both implementations.

Conclusion #

Like Command Handlers and Event Handlers, generic predicates give rise to a contravariant functor. This includes both the Specification pattern, Predicate<T>, and Func<T, bool>.

Are you noticing a pattern?

The Command Handler contravariant functor

An introduction to the Command Handler contravariant functor for object-oriented programmers.

This article is an instalment in an article series about contravariant functors. It assumes that you've read the introduction.

Asynchronous software architectures, such as those described in Enterprise Integration Patterns, often make good use of a pattern where Commands are (preferably immutable) Data Transfer Objects (DTOs) that are often placed on a persistent queue and later handled by a background process.

Even if you don't use asynchronous processing, separating command data from command handling can be beneficial for your software's granular architecture. In perhaps his most remarkable contribution to our book, Steven van Deursen describes how this pattern can greatly simplify how you deal with cross-cutting concerns.

Interface #

In DIPPP the interface is called ICommandService, but in this article I'll instead call it ICommandHandler. It's a generic interface with a single method:

public interface ICommandHandler<TCommand> { void Execute(TCommand command); }

The book explains how this interface enables you to gracefully handle cross-cutting concerns without any reflection magic. You can also peruse its example code base on GitHub. In this article, however, I'm using a fork of that code because I wanted to make the properties of contravariant functors stand out more clearly.

In the sample code base, an ASP.NET Controller delegates work to an injected ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory> called inventoryAdjuster.

[Route("inventory/adjustinventory")] public ActionResult AdjustInventory(AdjustInventoryViewModel viewModel) { if (!this.ModelState.IsValid) { return this.View(nameof(Index), this.Populate(viewModel)); } AdjustInventory command = viewModel.Command; this.inventoryAdjuster.Execute(command); this.TempData["SuccessMessage"] = "Inventory successfully adjusted."; return this.RedirectToAction(nameof(HomeController.Index), "Home"); }

There's a single implementation of ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory>, which is a class called AdjustInventoryService:

public class AdjustInventoryService : ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory> { private readonly IInventoryRepository repository; public AdjustInventoryService(IInventoryRepository repository) { if (repository == null) throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(repository)); this.repository = repository; } public void Execute(AdjustInventory command) { var productInventory = this.repository.GetByIdOrNull(command.ProductId) ?? new ProductInventory(command.ProductId); int quantityAdjustment = command.Quantity * (command.Decrease ? -1 : 1); productInventory = productInventory.AdjustQuantity(quantityAdjustment); if (productInventory.Quantity < 0) throw new InvalidOperationException("Can't decrease below 0."); this.repository.Save(productInventory); } }

The Execute method first loads the inventory data from the database, calculates how to adjust it, and saves it. This is all fine and good object-oriented design, and my intent with the present article isn't to point fingers at it. My intent is only to demonstrate how the ICommandHandler interface gives rise to a contravariant functor.

I'm using this particular code base because it provides a good setting for a realistic example.

Towards Domain-Driven Design #

Consider these two lines of code from AdjustInventoryService:

int quantityAdjustment = command.Quantity * (command.Decrease ? -1 : 1); productInventory = productInventory.AdjustQuantity(quantityAdjustment);

Doesn't that look like a case of Feature Envy? Doesn't this calculation belong better on another class? Which one? The AdjustInventory Command? That's one option, but in this style of architecture Commands are supposed to be dumb DTOs, so that may not be the best fit. ProductInventory? That may be more promising.

Before making that change, however, let's consider the current state of the class.

One of the changes I made in my fork of the code was to turn the ProductInventory class into an immutable Value Object, as recommended in DDD:

public sealed class ProductInventory { public ProductInventory(Guid id) : this(id, 0) { } public ProductInventory(Guid id, int quantity) { Id = id; Quantity = quantity; } public Guid Id { get; } public int Quantity { get; } public ProductInventory WithQuantity(int newQuantity) { return new ProductInventory(Id, newQuantity); } public ProductInventory AdjustQuantity(int adjustment) { return WithQuantity(Quantity + adjustment); } public override bool Equals(object obj) { return obj is ProductInventory inventory && Id.Equals(inventory.Id) && Quantity == inventory.Quantity; } public override int GetHashCode() { return HashCode.Combine(Id, Quantity); } }

That looks like a lot of code, but keep in mind that typing isn't the bottleneck - and besides, most of that code was written by various Visual Studio Quick Actions.

Let's try to add a Handle method to ProductInventory:

public ProductInventory Handle(AdjustInventory command) { var adjustment = command.Quantity * (command.Decrease ? -1 : 1); return AdjustQuantity(adjustment); }

While AdjustInventoryService isn't too difficult to unit test, it still does require setting up and configuring some Test Doubles. The new method, on the other hand, is actually a pure function, which means that it's trivial to unit test:

[Theory] [InlineData(0, false, 0, 0)] [InlineData(0, true, 0, 0)] [InlineData(0, false, 1, 1)] [InlineData(0, false, 2, 2)] [InlineData(1, false, 1, 2)] [InlineData(2, false, 3, 5)] [InlineData(5, true, 2, 3)] [InlineData(5, true, 5, 0)] public void Handle( int initial, bool decrease, int adjustment, int expected) { var sut = new ProductInventory(Guid.NewGuid(), initial); var command = new AdjustInventory { ProductId = sut.Id, Decrease = decrease, Quantity = adjustment }; var actual = sut.Handle(command); Assert.Equal(sut.WithQuantity(expected), actual); }

Now that the new function is available on ProductInventory, you can use it in AdjustInventoryService:

public void Execute(AdjustInventory command) { var productInventory = this.repository.GetByIdOrNull(command.ProductId) ?? new ProductInventory(command.ProductId); productInventory = productInventory.Handle(command); if (productInventory.Quantity < 0) throw new InvalidOperationException("Can't decrease below 0."); this.repository.Save(productInventory); }

The Execute method now delegates its central logic to ProductInventory.Handle.

Encapsulation #

If you consider the Execute method in its current incarnation, you may wonder why it checks whether the Quantity is negative. Shouldn't that be the responsibility of ProductInventory? Why do we even allow ProductInventory to enter an invalid state?

This breaks encapsulation. Encapsulation is one of the most misunderstood concepts in programming, but as I explain in my PluralSight course, as a minimum requirement, an object should not allow itself to be put into an invalid state.

How to better encapsulate ProductInventory? Add a Guard Clause to the constructor:

public ProductInventory(Guid id, int quantity) { if (quantity < 0) throw new ArgumentOutOfRangeException( nameof(quantity), "Negative quantity not allowed."); Id = id; Quantity = quantity; }

Again, such behaviour is trivial to drive with a unit test:

[Theory] [InlineData( -1)] [InlineData( -2)] [InlineData(-19)] public void SetNegativeQuantity(int negative) { var id = Guid.NewGuid(); Action action = () => new ProductInventory(id, negative); Assert.Throws<ArgumentOutOfRangeException>(action); }

With those changes in place, AdjustInventoryService becomes even simpler:

public void Execute(AdjustInventory command) { var productInventory = this.repository.GetByIdOrNull(command.ProductId) ?? new ProductInventory(command.ProductId); productInventory = productInventory.Handle(command); this.repository.Save(productInventory); }

Perhaps even so simple that the class begins to seem unwarranted.

Sandwich #

It's just a database Query, a single pure function call, and another database Command. In fact, it looks a lot like an impureim sandwich:

public void Execute(AdjustInventory command) { var productInventory = this.repository.GetByIdOrNull(command.ProductId) ?? new ProductInventory(command.ProductId); productInventory = productInventory.Handle(command); this.repository.Save(productInventory); }

In fact, it'd probably be more appropriate to move the null-handling closer to the other referentially transparent code:

public void Execute(AdjustInventory command) { var productInventory = this.repository.GetByIdOrNull(command.ProductId); productInventory = (productInventory ?? new ProductInventory(command.ProductId)).Handle(command); this.repository.Save(productInventory); }

Why do we need the AdjustInventoryService class, again?

Can't we move those three lines of code to the Controller? We could, but that might make testing the above AdjustInventory Controller action more difficult. After all, at the moment, the Controller has an injected ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory>, which is easy to replace with a Test Double.

If only we could somehow compose an ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory> from the above sandwich without having to define a class...

Contravariant functor #

Fortunately, an interface like ICommandHandler<T> gives rise to a contravariant functor. This will enable you to compose an ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory> object from the above constituent parts.

In order to enable contravariant mapping, you must add a ContraMap method:

public static ICommandHandler<T1> ContraMap<T, T1>( this ICommandHandler<T> source, Func<T1, T> selector) { Action<T1> action = x => source.Execute(selector(x)); return new DelegatingCommandHandler<T1>(action); }

Notice that, as explained in the overview article, in order to map from an ICommandHandler<T> to an ICommandHandler<T1>, the selector has to go the other way: from T1 to T. How this is possible will become more apparent with an example, which will follow later in the article.

The ContraMap method uses a DelegatingCommandHandler that wraps any Action<T>:

public class DelegatingCommandHandler<T> : ICommandHandler<T> { private readonly Action<T> action; public DelegatingCommandHandler(Action<T> action) { this.action = action; } public void Execute(T command) { action(command); } }

If you're now wondering whether Action<T> itself gives rise to a contravariant functor, then yes it does.

Identity law #

A ContraMap method with the right signature isn't enough to be a contravariant functor. It must also obey the contravariant functor laws. As usual, it's proper computer-science work to actually prove this, but you can write some tests to demonstrate the identity law for the ICommandHandler<T> interface. In this article, you'll see parametrised tests written with xUnit.net. First, the identity law:

[Theory] [InlineData("foo")] [InlineData("bar")] [InlineData("baz")] [InlineData("qux")] [InlineData("quux")] [InlineData("quuz")] [InlineData("corge")] [InlineData("grault")] [InlineData("garply")] public void IdentityLaw(string input) { var observations = new List<string>(); ICommandHandler<string> sut = new DelegatingCommandHandler<string>(observations.Add); T id<T>(T x) => x; ICommandHandler<string> projection = sut.ContraMap<string, string>(id); // Run both handlers sut.Execute(input); projection.Execute(input); Assert.Equal(2, observations.Count); Assert.Single(observations.Distinct()); }

In order to observe that the two handlers have identical behaviours, the test has to Execute both of them to verify that both observations are the same.

All test cases pass.

Composition law #

Like the above example, you can also write a parametrised test that demonstrates that ContraMap obeys the composition law for contravariant functors:

[Theory] [InlineData("foo")] [InlineData("bar")] [InlineData("baz")] [InlineData("qux")] [InlineData("quux")] [InlineData("quuz")] [InlineData("corge")] [InlineData("grault")] [InlineData("garply")] public void CompositionLaw(string input) { var observations = new List<TimeSpan>(); ICommandHandler<TimeSpan> sut = new DelegatingCommandHandler<TimeSpan>(observations.Add); Func<string, int> f = s => s.Length; Func<int, TimeSpan> g = i => TimeSpan.FromDays(i); ICommandHandler<string> projection1 = sut.ContraMap((string s) => g(f(s))); ICommandHandler<string> projection2 = sut.ContraMap(g).ContraMap(f); // Run both handlers projection1.Execute(input); projection2.Execute(input); Assert.Equal(2, observations.Count); Assert.Single(observations.Distinct()); }

This test defines two local functions, f and g. Once more, you can't directly compare methods for equality, so instead you have to Execute them to verify that they produce the same observable effect.

They do.

Composed inventory adjustment handler #

We can now return to the inventory adjustment example. You may recall that the Controller would Execute a command on an injected ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory>:

this.inventoryAdjuster.Execute(command);

As a first step, we can attempt to compose inventoryAdjuster on the fly:

ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory> inventoryAdjuster = new DelegatingCommandHandler<ProductInventory>(repository.Save) .ContraMap((ProductInventory inv) => (inv ?? new ProductInventory(command.ProductId)).Handle(command)) .ContraMap((AdjustInventory cmd) => repository.GetByIdOrNull(cmd.ProductId)); inventoryAdjuster.Execute(command);

Contra-mapping is hard to get one's head around, and to make matters worse, you have to read it from the bottom towards the top to understand what it does. It really is contrarian.

How do you arrive at something like this?

You start by looking at what you have. The Controller may already have an injected repository with various methods. repository.Save, for example, has this signature:

void Save(ProductInventory productInventory);

Since it has a void return type, you can treat repository.Save as an Action<ProductInventory>. Wrap it in a DelegatingCommandHandler and you have an ICommandHandler<ProductInventory>:

ICommandHandler<ProductInventory> inventoryAdjuster = new DelegatingCommandHandler<ProductInventory>(repository.Save);

That's not what you need, though. You need an ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory>. How do you get closer to that?

You already know from the AdjustInventoryService class that you can use a pure function as the core of the impureim sandwich. Try that and see what it gives you:

ICommandHandler<ProductInventory> inventoryAdjuster = new DelegatingCommandHandler<ProductInventory>(repository.Save) .ContraMap((ProductInventory inv) => (inv ?? new ProductInventory(command.ProductId)).Handle(command));

That doesn't change the type of the handler, but implements the desired functionality.

You have an ICommandHandler<ProductInventory> that you need to somehow map to an ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory>. How do you do that?

By supplying a function that goes the other way: from AdjustInventory to ProductInventory. Does such a method exist? Yes, it does, on the repository:

ProductInventory GetByIdOrNull(Guid id);

Or, close enough. While AdjustInventory is not a Guid, it comes with a Guid:

ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory> inventoryAdjuster = new DelegatingCommandHandler<ProductInventory>(repository.Save) .ContraMap((ProductInventory inv) => (inv ?? new ProductInventory(command.ProductId)).Handle(command)) .ContraMap((AdjustInventory cmd) => repository.GetByIdOrNull(cmd.ProductId));

That's cool, but unfortunately, this composition cheats. It closes over command, which is a run-time variable only available inside the AdjustInventory Controller action.

If we're allowed to compose the Command Handler inside the AdjustInventory method, we might as well just have written:

var inv = repository.GetByIdOrNull(command.ProductId); inv = (inv ?? new ProductInventory(command.ProductId)).Handle(command); repository.Save(inv);

This is clearly much simpler, so why don't we do that?

In this particular example, that's probably a better idea overall, but I'm trying to explain what is possible with contravariant functors. The goal here is to decouple the caller (the Controller) from the handler. We want to be able to define the handler outside of the Controller action.

That's what the AdjustInventory class does, but can we leverage the contravariant functor to compose an ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory> without adding a new class?

Composition without closures #

The use of a closure in the above composition is what disqualifies it. Is it possible to compose an ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory> when the command object is unavailable to close over?

Yes, but it isn't pretty:

ICommandHandler<AdjustInventory> inventoryAdjuster = new DelegatingCommandHandler<ProductInventory>(repository.Save) .ContraMap((ValueTuple<AdjustInventory, ProductInventory> t) => (t.Item2 ?? new ProductInventory(t.Item1.ProductId)).Handle(t.Item1)) .ContraMap((AdjustInventory cmd) => (cmd, repository.GetByIdOrNull(cmd.ProductId)));

You can let the composing function return a tuple of the original input value and the projected value. That's what the lowest ContraMap does. This means that the upper ContraMap receives this tuple to map. Not pretty, but possible.

I never said that this was the best way to address some of the concerns I've hinted at in this article. The purpose of the article was mainly to give you a sense of what a contravariant functor can do.

Action as a contravariant functor #

Wrapping an Action<T> in a DelegatingCommandHandler isn't necessary in order to form the contravariant functor. I only used the ICommandHandler interface as an object-oriented-friendly introduction to the example. In fact, any Action<T> gives rise to a contravariant functor with this ContraMap function:

public static Action<T1> ContraMap<T, T1>(this Action<T> source, Func<T1, T> selector) { return x => source(selector(x)); }

As you can tell, the function being returned is similar to the lambda expression used to implement ContraMap for ICommandHandler<T>.

This turns out to make little difference in the context of the examples shown here, so I'm not going to tire you with more example code.

Conclusion #

Any generic polymorphic interface or abstract method with a void return type gives rise to a contravariant functor. This includes the ICommandHandler<T> (originally ICommandService<T>) interface, but also another interface discussed in DIPPP: IEventHandler<TEvent>.

The utility of this insight may not be immediately apparent. Contrary to its built-in support for functors, C# doesn't have any language features that light up if you implement a ContraMap function. Even in Haskell where the Contravariant functor is available in the base library, I can't recall having ever used it.

Still, even if not a practical insight, the ubiquitous presence of contravariant functors in everyday programming 'building blocks' tells us something profound about the fabric of programming abstraction and polymorphism.

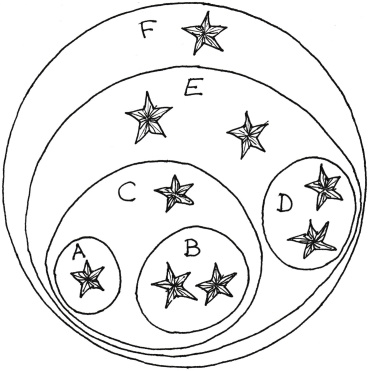

Contravariant functors

A more exotic kind of universal abstraction.

This article series is part of a larger series of articles about functors, applicatives, and other mappable containers.

So far in the article series, you've seen examples of mappable containers that map in the same direction of projections, so to speak. Let's unpack that.

Covariance recap #

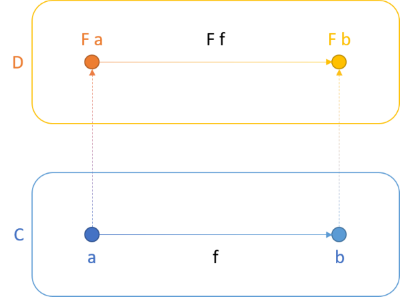

Functors, applicative functors, and bifunctors all follow the direction of projections. Consider the illustration from the article about functors:

The function f maps from a to b. You can think of a and b as two types, or two sets. For example, if a is the set of all strings, it might correspond to the type String. Likewise, if b is the set of all integers, then it corresponds to a type called Int. The function f would, in that case, have the type String -> Int; that is: it maps strings to integers. The most natural such function seems to be one that counts the number of characters in a string:

> f = length > f "foo" 3 > f "ploeh" 5

This little interactive session uses Haskell, but even if you've never heard about Haskell before, you should still be able to understand what's going on.

A functor is a container of values, for example a collection, a Maybe, a lazy computation, or many other things. If f maps from a to b, then lifting it to the functor F retains the direction. That's what the above figure illustrates. Not only does the functor project a to F a and b to F b, it also maps f to F f, which is F a -> F b.

For lists it might look like this:

> fmap f ["bar", "fnaah", "Gauguin"] [3,5,7]

Here fmap lifts the function String -> Int to [String] -> [Int]. Notice that the types 'go in the same direction' when you lift a function to the functor. The types vary with the function - they co-vary; hence covariance.

While applicative functors and bifunctors are more complex, they are still covariant. Consult, for example, the diagrams in my bifunctor article to get an intuitive sense that this still holds.

Contravariance #

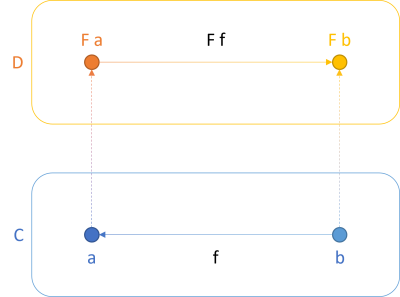

What happens if we change the direction of only one arrow? For example, we could change the direction of the f arrow, so that the function is now a function from b to a: b -> a. The figure would look like this:

This looks almost like the first figure, with one crucial difference: The lower arrow now goes from right to left. Notice that the upper arrow still goes from left to right: F a -> F b. In other words, the functor varies in the contrary direction than the projected function. It's contravariant.

This seems really odd. Why would anyone do that?

As is so often the case with universal abstractions, it's not so much a question of coming up with an odd concept and see what comes of it. It's actually an abstract description of some common programming constructs. In this series of articles, you'll see examples of some contravariant functors:

- The Command Handler contravariant functor

- The Specification contravariant functor

- The Equivalence contravariant functor

- Reader as a contravariant functor

- Functor variance compared to C#'s notion of variance

- Contravariant Dependency Injection

These aren't the only examples, but they should be enough to get the point across. Other examples include equivalence and comparison.

Lifting #

How do you lift a function f to a contravariant functor? For covariant functors (normally just called functors), Haskell has the fmap function, while in C# you'd be writing a family of Select methods. Let's compare. In Haskell, fmap has this type:

fmap :: Functor f => (a -> b) -> f a -> f b

You can read it like this: For any Functor f, fmap lifts a function of the type a -> b to a function of the type f a -> f b. Another way to read this is that given a function a -> b and a container of type f a, you can produce a container of type f b. Due to currying, these two interpretations are both correct.

In C#, you'd be writing a method on Functor<T> that looks like this:

public Functor<TResult> Select<TResult>(Func<T, TResult> selector)

This fits the later interpretation of fmap: Given an instance of Functor<T>, you can call Select with a Func<T, TResult> to produce a Functor<TResult>.

What does the equivalent function look like for contravariant functors? Haskell defines it as:

contramap :: Contravariant f => (b -> a) -> f a -> f b

You can read it like this: For any Contravariant functor f, contramap lifts a function (b -> a) to a function from f a to f b. Or, in the alternative (but equally valid) interpretation that matches C# better, given a function (b -> a) and an f a, you can produce an f b.

In C#, you'd be writing a method on Contravariant<T> that looks like this:

public Contravariant<T1> ContraMap<T1>(Func<T1, T> selector)

The actual generic type (here exemplified by Contravariant<T>) will differ, but the shape of the method will be the same. In order to map from Contravariant<T> to Contravariant<T1>, you need a function that goes the other way: Func<T1, T> goes from T1 to T.

In C#, the function name doesn't have to be ContraMap, since C# doesn't have any built-in understanding of contravariant functors - as opposed to functors, where a method called Select will light up some language features. In this article series I'll stick with ContraMap since I couldn't think of a better name.

Laws #

Like functors, applicative functors, monoids, and other universal abstractions, contravariant functors are characterised by simple laws. The contravariant functor laws are equivalent to the (covariant) functor laws: identity and composition.

In pseudo-Haskell, we can express the identity law as:

contramap id = id

and the composition law as:

contramap (g . f) = contramap f . contramap g

The identity law is equivalent to the first functor law. It states that mapping a contravariant functor with the identity function is equivalent to a no-op. The identity function is a function that returns all input unchanged. (It's called the identity function because it's the identity for the endomorphism monoid.) In F# and Haskell, this is simply a built-in function called id.

In C#, you can write a demonstration of the law as a unit test. Here's the essential part of such a test:

Func<string, string> id = x => x; Contravariant<string> sut = createContravariant(); Assert.Equal(sut, sut.ContraMap(id), comparer);

The ContraMap method does return a new object, so a custom comparer is required to evaluate whether sut is equal to sut.ContraMap(id).

The composition law governs how composition works. Again, notice how lifting reverses the order of functions. In C#, the relevant unit test code might look like this:

Func<string, int> f = s => s.Length; Func<int, TimeSpan> g = i => TimeSpan.FromDays(i); Contravariant<TimeSpan> sut = createContravariant(); Assert.Equal( sut.ContraMap((string s) => g(f(s))), sut.ContraMap(g).ContraMap(f), comparer);

This may actually look less surprising in C# than it does in Haskell. Here the lifted composition doesn't look reversed, but that's because C# doesn't have a composition operator for raw functions, so I instead wrote it as a lambda expression: (string s) => g(f(s)). If you contrast this C# example with the equivalent assertion of the (covariant) second functor law, you can see that the function order is flipped: f(g(i)).

Assert.Equal(sut.Select(g).Select(f), sut.Select(i => f(g(i))));

It can be difficult to get your head around the order of contravariant composition without some examples. I'll provide examples in the following articles, but I wanted to leave the definition of the two contravariant functor laws here for reference.

Conclusion #

Contravariant functors are functors that map in the opposite direction of an underlying function. This seems counter-intuitive but describes the actual behaviour of quite normal functions.

This is hardly illuminating without some examples, so without further ado, let's proceed to the first one.

The Reader functor

Normal functions form functors. An article for object-oriented programmers.

This article is an instalment in an article series about functors. In a previous article you saw, for example, how to implement the Maybe functor in C#. In this article, you'll see another functor example: Reader.

The Reader functor is similar to the Identity functor in the sense that it seems practically useless. If that's the case, then why care about it?

As I wrote about the Identity functor:

"The inutility of Identity doesn't mean that it doesn't exist. The Identity functor exists, whether it's useful or not. You can ignore it, but it still exists. In C# or F# I've never had any use for it (although I've described it before), while it turns out to be occasionally useful in Haskell, where it's built-in. The value of Identity is language-dependent."

The same holds for Reader. It exists. Furthermore, it teaches us something important about ordinary functions.

Reader interface #

Imagine the following interface:

public interface IReader<R, A> { A Run(R environment); }

An IReader object can produce a value of the type A when given a value of the type R. The input is typically called the environment. A Reader reads the environment and produces a value. A possible (although not particularly useful) implementation might be:

public class GuidToStringReader : IReader<Guid, string> { private readonly string format; public GuidToStringReader(string format) { this.format = format; } public string Run(Guid environment) { return environment.ToString(format); } }

This may be a silly example, but it illustrates that a a simple class can implement a constructed version of the interface: IReader<Guid, string>. It also demonstrates that a class can take further arguments via its constructor.

While the IReader interface only takes a single input argument, we know that an argument list is isomorphic to a parameter object or tuple. Thus, IReader is equivalent to every possible function type - up to isomorphism, assuming that unit is also a value.

While the practical utility of the Reader functor may not be immediately apparent, it's hard to argue that it isn't ubiquitous. Every method is (with a bit of hand-waving) a Reader.

Functor #

You can turn the IReader interface into a functor by adding an appropriate Select method:

public static IReader<R, B> Select<A, B, R>(this IReader<R, A> reader, Func<A, B> selector) { return new FuncReader<R, B>(r => selector(reader.Run(r))); } private sealed class FuncReader<R, A> : IReader<R, A> { private readonly Func<R, A> func; public FuncReader(Func<R, A> func) { this.func = func; } public A Run(R environment) { return func(environment); } }

The implementation of Select requires a private class to capture the projected function. FuncReader is, however, an implementation detail.

When you Run a Reader, the output is a value of the type A, and since selector is a function that takes an A value as input, you can use the output of Run as input to selector. Thus, the return type of the lambda expression r => selector(reader.Run(r)) is B. Therefore, Select returns an IReader<R, B>.

Here's an example of using the Select method to project an IReader<Guid, string> to IReader<Guid, int>:

[Fact] public void WrappedFunctorExample() { IReader<Guid, string> r = new GuidToStringReader("N"); IReader<Guid, int> projected = r.Select(s => s.Count(c => c.IsDigit())); var input = new Guid("{CAB5397D-3CF9-40BB-8CBD-B3243B7FDC23}"); Assert.Equal(16, projected.Run(input)); }

The expected result is 16 because the input Guid contains 16 digits (the numbers from 0 to 9). Count them if you don't believe me.

As usual, you can also use query syntax:

[Fact] public void QuerySyntaxFunctorExample() { var projected = from s in new GuidToStringReader("N") select TimeSpan.FromMinutes(s.Length); var input = new Guid("{FE2AB9C6-DDB1-466C-8AAA-C70E02F964B9}"); Assert.Equal(32, projected.Run(input).TotalMinutes); }

The actual computation shown here makes little sense, since the result will always be 32, but it illustrates that arbitrary projections are possible.

Raw functions #

The IReader<R, A> interface isn't really necessary. It was just meant as an introduction to make things a bit easier for object-oriented programmers. You can write a similar Select extension method for any Func<R, A>:

public static Func<R, B> Select<A, B, R>(this Func<R, A> func, Func<A, B> selector) { return r => selector(func(r)); }

Compare this implementation to the one above. It's essentially the same lambda expression, but now Select returns the raw function instead of wrapping it in a class.

In the following, I'll use raw functions instead of the IReader interface.

First functor law #

The Select method obeys the first functor law. As usual, it's proper computer-science work to actually prove this, but you can write some tests to demonstrate the first functor law for the IReader<R, A> interface. In this article, you'll see parametrised tests written with xUnit.net. First, the first functor law:

[Theory] [InlineData("")] [InlineData("foo")] [InlineData("bar")] [InlineData("corge")] [InlineData("antidisestablishmentarianism")] public void FirstFunctorLaw(string input) { T id<T>(T x) => x; Func<string, int> f = s => s.Length; Func<string, int> actual = f.Select(id); Assert.Equal(f(input), actual(input)); }

The 'original' Reader f (for function) takes a string as input and returns its length. The id function (which isn't built-in in C#) is implemented as a local function. It returns whichever input it's given.

Since id returns any input without modifying it, it'll also return any number produced by f without modification.

To evaluate whether f is equal to f.Select(id), the assertion calls both functions with the same input. If the functions have equal behaviour, they ought to return the same output.

The above test cases all pass.

Second functor law #

Like the above example, you can also write a parametrised test that demonstrates that a function (Reader) obeys the second functor law:

[Theory] [InlineData("")] [InlineData("foo")] [InlineData("bar")] [InlineData("corge")] [InlineData("antidisestablishmentarianism")] public void SecondFunctorLaw(string input) { Func<string, int> h = s => s.Length; Func<int, bool> g = i => i % 2 == 0; Func<bool, char> f = b => b ? 't' : 'f'; Assert.Equal( h.Select(g).Select(f)(input), h.Select(i => f(g(i)))(input)); }

You can't easily compare two different functions for equality, so, like above, this test defines equality as the functions producing the same result when you invoke them.

Again, while the test doesn't prove anything, it demonstrates that for the five test cases, it doesn't matter if you project the 'original' Reader h in one or two steps.

Haskell #

In Haskell, normal functions a -> b are already Functor instances, which means that you can easily replicate the functions from the SecondFunctorLaw test:

> h = length > g i = i `mod` 2 == 0 > f b = if b then 't' else 'f' > (fmap f $ fmap g $ h) "ploeh" 'f'

Here f, g, and h are equivalent to their above C# namesakes, while the last line composes the functions stepwise and calls the composition with the input string "ploeh". In Haskell you generally read code from right to left, so this composition corresponds to h.Select(g).Select(f).

Conclusion #

Functions give rise to functors, usually known collectively as the Reader functor. Even in Haskell where this fact is ingrained into the fabric of the language, I rarely make use of it. It just is. In C#, it's likely to be even less useful for practical programming purposes.

That a function a -> b forms a functor, however, is an important insight into just what a function actually is. It describes an essential property of functions. In itself this may still seem underwhelming, but mixed with some other properties (that I'll describe in a future article) it can produce some profound insights. So stay tuned.

Next: The IO functor.

Am I stuck in a local maximum?

On long-standing controversies, biases, and failures of communication.

If you can stay out of politics, Twitter can be a great place to engage in robust discussions. I mostly follow and engage with people in the programming community, and every so often find myself involved in a discussion about one of several long-standing controversies. No, not the tabs-versus-spaces debate, but other debates such as functional versus object-oriented programming, dynamic versus static typing, or oral versus written collaboration.

It happened again the past week, but while this article is a reaction, it's not about the specific debacle. Thus, I'm not going to link to the tweets in question.

These discussion usually leave me wondering why people with decades of industry experience seem to have such profound disagreements.

I might be wrong #

Increasingly, I find myself disagreeing with my heroes. This isn't a comfortable position. Could I be wrong?

I've definitely been wrong before. For example, in my article Types + Properties = Software, I wrote about type systems:

"To the far right, we have a hypothetical language with such a strong type system that, indeed, if it compiles, it works."