ploeh blog danish software design

Epistemology of interaction testing

How do we know that components interact correctly?

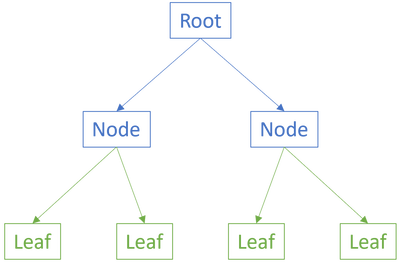

Most software systems are composed as a graph of components. To be clear, I use the word component loosely to mean a collection of functionality - it may be an object, a module, a function, a data type, or perhaps something else I haven't thought of. Some components deal with the bigger picture and will typically coordinate other components that perform more specific tasks. If we think of a component graph as a tree, then some components are leaves.

Leaf components, being self-contained and without dependencies, are typically the easiest to test. Most test-driven development (TDD) katas focus on these kinds of components: Tennis, bowling, diamond, Roman numerals, gossiping bus drivers, and so on. Even the legacy security manager kata is simple and quite self-contained. There's nothing wrong with that, and there's good reason to keep such exercises simple. After all, you want to be able to complete a kata in a few hours. You can hardly do that if the exercise is to develop an entire web site with user interface, persistent data storage, security, data validation, business logic, third-party integration, emails, instrumentation and logging, and so on.

This means that even if you get good at TDD against 'leaf' functionality, you may be struggling when it comes to higher-level components. How does one unit test code that has dependencies?

Interaction-based testing #

A common solution is to invert the dependencies. You can, for example, use Dependency Injection to inject Test Doubles into the System Under Test (SUT). This enables you to control the behaviour of the dependencies and to verify that the SUT behaves as expected. Not only that, but you can also verify that the SUT interacts with the dependencies as expected. This is called interaction-based testing. It is, perhaps, the most common form of unit testing in the industry, and exemplary explained in Growing Object-Oriented Software, Guided by Tests.

The kinds of Test Doubles most useful with interaction-based testing are Stubs and Mocks. They are, however, problematic because they break encapsulation. And encapsulation, to be clear, is also a concern in functional programming.

I have already described how to move from interaction-based to state-based testing, and why functional programming is intrinsically more testable.

How to test composition of pure functions? #

When you adopt functional programming (FP) you'll sooner or later need to compose or orchestrate pure functions. How do you test that the composition of pure functions is correct? That's what you can test with a Mock or Spy.

You've developed component A, perhaps as a higher-order function, that depends on another component B. You want to test that A correctly interacts with B, but if interaction-based testing is no longer 'allowed' (because it breaks encapsulation), then what do you do?

For a long time, I pondered that question myself, while I was busy enjoying FP making most things easier. It took me some time to understand that the answer, as is often the case, is mu. I'll get back to that later.

I'm not the only one struggling with this question. Sergei Rogovtcev writes and asks what I interpret as the same question:

"I do have a component A, which is, frankly, some controller doing some checks and processing around a fairly complex state. This process can have several outcomes, let's call them Success, Fail, and Missing (the actual states are not important, but I'd like to have more than two). Then we have a component B, which is responsible for the rendering of the result. Of course, three different states lead to three different renderings, but the renderings are also influenced by state (let's say we have browser, mobile and native clients, and we need to provide different renderings). Originally the components are objects, B having three separate methods, but I can express them as pure functions, at least for the purpose of this discussion - A, and then BSuccess, BFail and BMissing. I can easily test each part of B in isolation; the problem comes when I need to test A, which calls different parts of B. If I use mocks, the solution is simple - I inject a mock of B to A, and then verify that A calls appropriate parts according to the process result. This requires knowing the innards of A, but otherwise it is a well-known and well-understood approach. But if I want to avoid mocks, what do I do? I cannot test A without relying on some code path in B, and this to me means that I'm losing the benefits of unit testing and entering the realm of integration testing."

In his email Sergei Rogovtcev has explicitly given me permission to quote him and engage with this question. As I've outlined, I've grappled with that question myself, so I find the question worthwhile. I can't, however, work with it without questioning the premise. This is not an attack on Sergei Rogovtcev; after all, I had that question myself, so any critique I make is directed as much at my former self as at him.

Axiomatic versus scientific knowledge #

It may be helpful to elevate the discussion. How do we know that software (or a subsystem thereof) works? You could say that one answer to that is: Passing tests. If all tests are passing, we may have high confidence that the system works.

In the parlance of Sergei Rogovtcev, we can easily unit test component B because it's composed from pure functions.

How do we unit test component A, though? With Mocks and Stubs, you can prove that the interaction works as intended. The keyword here is prove. If you assume that component B works correctly, 'all' you have to do is to demonstrate that component A correctly interacts with component B. I used to do that all the time and called it data-flow verification or structural inspection. The idea was that if you could demonstrate that component A correctly interacts with any LSP-compliant implementation of component B, and then also demonstrate that in reality (when composed in the Composition Root) component A is composed with a component B that has also been demonstrated to work correctly, then the (sub-)system works correctly.

This is almost like a mathematical proof. First prove lemma B, then prove theorem A using lemma B. Finally, state corollary C: b is a special case handled by lemma B, so therefore a is covered by theorem A. Q.E.D.

It's a logical and deductive approach to the problem of verifying the composition of the whole from verified parts. It's almost mathematical in the sense that it tries to erect an axiomatic system.

It's also fundamentally flawed.

I didn't understand that a decade ago, and in practice, the method worked well enough - apart from all the problems stemming from poor encapsulation. The problem with that approach is that an axiomatic system is only as strong as its axioms. What are the axioms in this system? The axioms, or premises, are that each of the components (A and B) are already correct. Based on these premises, this testing approach then proves that the composition is also correct.

How do we know that the components work correctly?

In this context, the answer is that they pass all tests. This, however, doesn't constitute any kind of proof. Rather, this is experimental knowledge, more reminiscent of science than of mathematics.

Why are we trying to prove, then, that composition works correctly? Why not just test it?

This observation cuts to the heart of the epistemology of testing. How do we know that software works? Typically not by proving it correct, but by subjecting it to experiments. As I've also outlined in Code That Fits in Your Head, we can regard automated tests as scientific experiments that we repeat over and over.

Integration testing #

To outline the argument so far: While you can use Mocks and Spies to verify that a component correctly interacts with another component, this may be overkill. You're essentially trying to prove a conjecture based on doubtful evidence.

Does it really matter that two components interact correctly? Aren't the components implementation details? Do users care?

Users and other stakeholders care about the behaviour of the software system. Why not test that?

This is, unfortunately, easier said than done. Sergei Rogovtcev strongly implies that he isn't keen on integration testing. While he doesn't explicitly state why, there are good reasons to be wary of integration testing. As J.B. Rainsberger eloquently explained, a major problem with integration testing is the combinatorial explosion of test cases. If you ought to write 53,000 test cases to cover all combinations of pathways through integrated components, which test cases do you write? Surely not all 53,000.

J.B. Rainsberger's argument is that if you're going to write no more than a dozen unit tests, you're unlikely to cover enough test cases to be confident that the system works.

What if, however, you could write hundreds or thousands of test cases?

Property-based testing #

You may recall that the premise of this article is functional programming (FP), where property-based testing is a common testing technique. While you can, to a degree, also use this technique in object-oriented programming (OOP), it's often difficult because of side effects and non-deterministic behaviour.

When you write a property-based test, you write a single piece of code that evaluates a property of the SUT. The property looks like a parametrised unit test; the difference is that the input is generated randomly, but in a fashion you can control. This enables you to write hundreds or thousands of test cases without having to write them explicitly.

Thus, epistemologically, you can use property-based testing with integrated components to produce confidence that the (sub-)system works. In practice, I find that the confidence I get from this technique is at least as high as the one I used to get from unit testing with Stubs and Spies.

Examples #

All of this is abstract and theoretical, I realise. An example would be handy right about now. Such examples, however, are complex enough to warrant their own articles:

- Confidence from Facade Tests

- An abstract example of refactoring from interaction-based to property-based testing

- A restaurant example of refactoring from example-based to property-based testing

- Refactoring pure function composition without breaking existing tests

- When is an implementation detail an implementation detail?

Sergei Rogovtcev was kind enough to furnish a rather abstract, but minimal and self-contained, example. I'll go through that first, and then follow up with a more realistic example.

Conclusion #

How do you know that a software system works correctly? Ultimately, if it behaves in the way it's supposed to, it works correctly. Testing an entire system from the outside, however, is rarely viable in itself. The number of possible test cases is just too large.

You can partially address that problem by decomposing the system into components. You can then test the components individually, and verify that they interact correctly. This last part is the topic of this article. A common way to to address this problem is to use Mocks and Spies to prove interactions correct. It does solve the problem of correctness quite neatly, but has the undesirable side effect of making the tests brittle.

An alternative is to use property-based testing to verify that the components integrate correctly. Rather than something that looks like a proof, this is a question of numbers. Throw enough random test cases at the system, and you'll be confident that it works. How many? Enough.

Next: Confidence from Facade Tests.

Contravariant functors as invariant functors

Another most likely useless set of invariant functors that nonetheless exist.

This article is part of a series of articles about invariant functors. An invariant functor is a functor that is neither covariant nor contravariant. See the series introduction for more details.

It turns out that all contravariant functors are also invariant functors.

Is this useful? Let me, like in the previous article, be honest and say that if it is, I'm not aware of it. Thus, if you're interested in practical applications, you can stop reading here. This article contains nothing of practical use - as far as I can tell.

Because it's there #

Why describe something of no practical use?

Why do some people climb Mount Everest? Because it's there, or for other irrational reasons. Which is fine. I've no personal goals that involve climbing mountains, but I happily engage in other irrational and subjective activities.

One of them, apparently, is to write articles of software constructs of no practical use, because it's there.

All contravariant functors are also invariant functors, even if that's of no practical use. That's just the way it is. This article explains how, and shows a few (useless) examples.

I'll start with a few Haskell examples and then move on to showing the equivalent examples in C#. If you're unfamiliar with Haskell, you can skip that section.

Haskell package #

For Haskell you can find an existing definition and implementations in the invariant package. It already makes most 'common' contravariant functors Invariant instances, including Predicate, Comparison, and Equivalence. Here's an example of using invmap with a predicate.

First, we need a predicate. Consider a function that evaluates whether a number is divisible by three:

isDivisbleBy3 :: Integral a => a -> Bool isDivisbleBy3 = (0 ==) . (`mod` 3)

While this is already conceptually a contravariant functor, in order to make it an Invariant instance, we have to enclose it in the Predicate wrapper:

ghci> :t Predicate isDivisbleBy3 Predicate isDivisbleBy3 :: Integral a => Predicate a

This is a predicate of some kind of integer. What if we wanted to know if a given duration represented a number of picoseconds divisible by three? Silly example, I know, but in order to demonstrate invariant mapping, we need types that are isomorphic, and NominalDiffTime is isomorphic to a number of picoseconds via its Enum instance.

p :: Enum a => Predicate a p = invmap toEnum fromEnum $ Predicate isDivisbleBy3

In other words, it's possible to map the Integral predicate to an Enum predicate, and since NominalDiffTime is an Enum instance, you can now evaluate various durations:

ghci> (getPredicate p) $ secondsToNominalDiffTime 60 True ghci> (getPredicate p) $ secondsToNominalDiffTime 61 False

This is, as I've already announced, hardly useful, but it's still possible. Unless you have an API that requires an Invariant instance, it's also redundant, because you could just have used contramap with the predicate:

ghci> (getPredicate $ contramap fromEnum $ Predicate isDivisbleBy3) $ secondsToNominalDiffTime 60 True ghci> (getPredicate $ contramap fromEnum $ Predicate isDivisbleBy3) $ secondsToNominalDiffTime 61 False

When mapping a contravariant functor, only the contravariant mapping argument is required. The Invariant instances for Contravariant simply ignores the covariant mapping argument.

Specification as an invariant functor in C# #

My earlier article The Specification contravariant functor takes a more object-oriented view on predicates by examining the Specification pattern.

As outlined in the introduction, while it's possible to add a method called InvMap, it'd be more idiomatic to add a non-standard Select method:

public static ISpecification<T1> Select<T, T1>( this ISpecification<T> source, Func<T, T1> tToT1, Func<T1, T> t1ToT) { return source.ContraMap(t1ToT); }

This implementation ignores tToT1 and delegates to the existing ContraMap method.

Here's a unit test that demonstrates an example equivalent to the above Haskell example:

[Theory] [InlineData(60, true)] [InlineData(61, false)] public void InvariantMappingExample(long seconds, bool expected) { ISpecification<long> spec = new IsDivisibleBy3Specification(); ISpecification<TimeSpan> mappedSpec = spec.Select(ticks => new TimeSpan(ticks), ts => ts.Ticks); Assert.Equal( expected, mappedSpec.IsSatisfiedBy(TimeSpan.FromSeconds(seconds))); }

Again, while this is hardly useful, it's possible.

Conclusion #

All contravariant functors are invariant functors. You simply use the 'normal' contravariant mapping function (contramap in Haskell). This enables you to add an invariant mapping (invmap) that only uses the contravariant argument (b -> a) and ignores the covariant argument (a -> b).

Invariant functors are, however, not particularly useful, so neither is this result. Still, it's there, so deserves a mention. Enough of that, though.

Next: Monads.

Built-in alternatives to applicative assertions

Why make things so complicated?

Several readers reacted to my small article series on applicative assertions, pointing out that error-collecting assertions are already supported in more than one unit-testing framework.

"In the Java world this seems similar to the result gained by Soft Assertions in AssertJ. https://assertj.github.io/doc/#assertj-c... if you’re after a target for functionality (without the adventures through monad land)"

While I'm not familiar with the details of Java unit-testing frameworks, the situation is similar in .NET, it turns out.

"Did you know there is Assert.Multiple in NUnit and now also in xUnit .Net? It seems to have quite an overlap with what you're doing here.

"For a quick overview, I found this blogpost helpful: https://www.thomasbogholm.net/2021/11/25/xunit-2-4-2-pre-multiple-asserts-in-one-test/"

I'm not surprised to learn that something like this exists, but let's take a quick look.

NUnit Assert.Multiple #

Let's begin with NUnit, as this seems to be the first .NET unit-testing framework to support error-collecting assertions. As a beginning, the documentation example works as it's supposed to:

[Test] public void ComplexNumberTest() { ComplexNumber result = SomeCalculation(); Assert.Multiple(() => { Assert.AreEqual(5.2, result.RealPart, "Real part"); Assert.AreEqual(3.9, result.ImaginaryPart, "Imaginary part"); }); }

When you run the test, it fails (as expected) with this error message:

Message: Multiple failures or warnings in test: 1) Real part Expected: 5.2000000000000002d But was: 5.0999999999999996d 2) Imaginary part Expected: 3.8999999999999999d But was: 4.0d

That seems to work well enough, but how does it actually work? I'm not interested in reading the NUnit source code - after all, the concept of encapsulation is that one should be able to make use of the capabilities of an object without knowing all implementation details. Instead, I'll guess: Perhaps Assert.Multiple executes the code block in a try/catch block and collects the various exceptions thrown by the nested assertions.

Does it catch all exception types, or only a subset?

Let's try with the kind of composed assertion that I previously investigated:

[Test] public void HttpExample() { var deleteResp = new HttpResponseMessage(HttpStatusCode.BadRequest); var getResp = new HttpResponseMessage(HttpStatusCode.OK); Assert.Multiple(() => { deleteResp.EnsureSuccessStatusCode(); Assert.That(getResp.StatusCode, Is.EqualTo(HttpStatusCode.NotFound)); }); }

This test fails (again, as expected). What's the error message?

Message: System.Net.Http.HttpRequestException :↩ Response status code does not indicate success: 400 (Bad Request).

(I've wrapped the result over multiple lines for readability. The ↩ symbol indicates where I've wrapped the text. I'll do that again later in this article.)

Notice that I'm using EnsureSuccessStatusCode as an assertion. This seems to spoil the behaviour of Assert.Multiple. It only reports the first status code error, but not the second one.

I admit that I don't fully understand what's going on here. In fact, I have taken a cursory glance at the relevant NUnit source code without being enlightened.

One hypothesis might be that NUnit assertions throw special Exception sub-types that Assert.Multiple catch. In order to test that, I wrote a few more tests in F# with Unquote, assuming that, since Unquote hardly throws NUnit exceptions, the behaviour might be similar to above.

[<Test>] let Test4 () = let x = 1 let y = 2 let z = 3 Assert.Multiple (fun () -> x =! y y =! z)

The =! operator is an Unquote operator that I usually read as must equal. How does that error message look?

Message: Multiple failures or warnings in test: 1) 1 = 2 false 2) 2 = 3 false

Somehow, Assert.Multiple understands Unquote error messages, but not HttpRequestException. As I wrote, I don't fully understand why it behaves this way. To a degree, I'm intellectually curious enough that I'd like to know. On the other hand, from a maintainability perspective, as a user of NUnit, I shouldn't have to understand such details.

xUnit.net Assert.Multiple #

How fares the xUnit.net port of Assert.Multiple?

[Fact] public void HttpExample() { var deleteResp = new HttpResponseMessage(HttpStatusCode.BadRequest); var getResp = new HttpResponseMessage(HttpStatusCode.OK); Assert.Multiple( () => deleteResp.EnsureSuccessStatusCode(), () => Assert.Equal(HttpStatusCode.NotFound, getResp.StatusCode)); }

The API is, you'll notice, not quite identical. Where the NUnit Assert.Multiple method takes a single delegate as input, the xUnit.net method takes an array of actions. The difference is not only at the level of API; the behaviour is different, too:

Message: Multiple failures were encountered: ---- System.Net.Http.HttpRequestException :↩ Response status code does not indicate success: 400 (Bad Request). ---- Assert.Equal() Failure Expected: NotFound Actual: OK

This error message reports both problems, as we'd like it to do.

I also tried writing equivalent tests in F#, with and without Unquote, and they behave consistently with this result.

If I had to use something like Assert.Multiple, I'd trust the xUnit.net variant more than NUnit's implementation.

Assertion scopes #

Apparently, Fluent Assertions offers yet another alternative.

"Hey @ploeh, been reading your applicative assertion series. I recently discovered Assertion Scopes, so I'm wondering what is your take on them since it seems to me they are solving this problem in C# already. https://fluentassertions.com/introduction#assertion-scopes"

The linked documentation contains this example:

[Fact] public void DocExample() { using (new AssertionScope()) { 5.Should().Be(10); "Actual".Should().Be("Expected"); } }

It fails in the expected manner:

Message: Expected value to be 10, but found 5 (difference of -5). Expected string to be "Expected" with a length of 8, but "Actual" has a length of 6,↩ differs near "Act" (index 0).

How does it fare when subjected to the EnsureSuccessStatusCode test?

[Fact] public void HttpExample() { var deleteResp = new HttpResponseMessage(HttpStatusCode.BadRequest); var getResp = new HttpResponseMessage(HttpStatusCode.OK); using (new AssertionScope()) { deleteResp.EnsureSuccessStatusCode(); getResp.StatusCode.Should().Be(HttpStatusCode.NotFound); } }

That test produces this error output:

Message: System.Net.Http.HttpRequestException :↩ Response status code does not indicate success: 400 (Bad Request).

Again, EnsureSuccessStatusCode prevents further assertions from being evaluated. I can't say that I'm that surprised.

Implicit or explicit #

You might protest that using EnsureSuccessStatusCode and treating the resulting HttpRequestException as an assertion is unfair and unrealistic. Possibly. As usual, such considerations are subject to a multitude of considerations, and there's no one-size-fits-all answer.

My intent with this article isn't to attack or belittle the APIs I've examined. Rather, I wanted to explore their boundaries by stress-testing them. That's one way to gain a better understanding. Being aware of an API's limitations and quirks can prevent subtle bugs.

Even if you'd never use EnsureSuccessStatusCode as an assertion, perhaps you or a colleague might inadvertently do something to the same effect.

I'm not surprised that both NUnit's Assert.Multiple and Fluent Assertions' AssertionScope behaves in a less consistent manner than xUnit.net's Assert.Multiple. The clue is in the API.

The xUnit.net API looks like this:

public static void Multiple(params Action[] checks)

Notice that each assertion is explicitly a separate action. This enables the implementation to isolate it and treat it independently of other actions.

Neither the NUnit nor the Fluent Assertions API is that explicit. Instead, you can write arbitrary code inside the 'scope' of multiple assertions. For AssertionScope, the notion of a 'scope' is plain to see. For the NUnit API it's more implicit, but the scope is effectively the extent of the method:

public static void Multiple(TestDelegate testDelegate)

That testDelegate can have as many (nested, even) assertions as you'd like, so the Multiple implementation needs to somehow demarcate when it begins and when it ends.

The testDelegate can be implemented in a different file, or even in a different library, and it has no way to communicate or coordinate with its surrounding scope. This reminds me of an Ambient Context, an idiom that Steven van Deursen convinced me was an anti-pattern. The surrounding context changes the behaviour of the code block it surrounds, and it's quite implicit.

Explicit is better than implicit.

The xUnit.net API, at least, looks a bit saner. Still, this kind of API is quirky enough that it reminds me of Greenspun's tenth rule; that these APIs are ad-hoc, informally-specified, bug-ridden, slow implementations of half of applicative functors.

Conclusion #

Not surprisingly, popular unit-testing and assertion libraries come with facilities to compose assertions. Also, not surprisingly, these APIs are crude and require you to learn their implementation details.

Would I use them if I had to? I probably would. As Rich Hickey put it, they're already at hand. That makes them easy, but not necessarily simple. APIs that compel you to learn their internal implementation details aren't simple.

Universal abstractions, on the other hand, you only have to learn one time. Once you understand what an applicative functor is, you know what to expect from it, and which capabilities it has.

In languages with good support for applicative functors, I would favour an assertion API based on that abstraction, if given a choice. At the moment, though, that's not much of an option. Even HUnit assertions are based on side effects.

Comments

Just a reminder: in .NET, method's execution cannot be resumed after an exception is thrown, there is just simply no way to do this, at all. Which means that NUnit's Assert.Multiple absolutely cannot work the way you guess it probably does, by running the delegate and resuming its execution after it throws an exception until the delegate returns.

How could it work then? Well, considering that documentation to almost every Assert's method has "Returns without throwing an exception when inside a multiple assert block" line in it, I would assume that Assert.Multiple sets a global flag which makes actual assertions to store the failures in some global hidden context instead on throwing them, then runs the delegate and after it finishes or throws, collects and clears all those failures from the context and resets the global flag.

Cursory inspection of NUnit's source code supports this idea, except that apparently it's not just a boolean flag but a "depth" counter; and assertions report the failures just the way I've speculated. I personally hate such side-channels but you have to admit, they allow for some nifty, seemingly impossible magical tricks (a.k.a. "spooky action at the distance").

Also, why do you assume that Unquote would not throw NUnit's assertions? It literally has "Unquote integrates configuration-free with all exception-based unit testing frameworks including xUnit.net, NUnit, MbUnit, Fuchu, and MSTest" in its README, and indeed, if you look at its source code, you'll see that at runtime it tries to locate any testing framework it's aware of and use its assertions. More funny party tricks, this time with reflection!

I understand that after working in more pure/functional programming environments one does start to slowly forget about those terrible things, but: those horrorterrors still exist, and people keep making more of them. Now, if you can, have a good night :)

Joker_vD, thank you for explaining those details. I admit that I hadn't thought too deeply about implementation details, for the reasons I briefly mentioned in the post.

"I understand that after working in more pure/functional programming environments one does start to slowly forget about those terrible things"

Yes, that summarises my current thinking well, I'm afraid.

NUnit has Assert.DoesNotThrow and Fluent Assertions has .Should().NotThrow(). I did not check Fluent Assertions, but NUnit does gather failures of Assert.DoesNotThrow inside Assert.Multiple into a multi-error report. One might argue that asserting that a delegate should not throw is another application of the "explicit is better than implicit" philosophy. Here's what Fluent Assertions has to say on that matter:

"We know that a unit test will fail anyhow if an exception was thrown, but this syntax returns a clearer description of the exception that was thrown and fits better to the AAA syntax."

As a side note, you might also want to take a look on NUnits Assert.That syntax. It allows to construct complex conditions tested against a single actual value:

int actual = 3; Assert.That (actual, Is.GreaterThan (0).And.LessThanOrEqualTo (2).And.Matches (Has.Property ("P").EqualTo ("a")));

A failure is then reported like this:

Expected: greater than 0 and less than or equal to 2 and property P equal to "a" But was: 3

Max, thank you for writing. I have to admit that I never understood the point of NUnit's constraint model, but your example clearly illustrates how it may be useful. It enables you to compose assertions.

It's interesting to try to understand the underlying reason for that. I took a cursory glance at that IResolveConstraint API, and as far as I can tell, it may form a monoid (I'm not entirely sure about the ConstraintStatus enum, but even so, it may be 'close enough' to be composable).

I can see how that may be useful when making assertions against complex objects (i.e. object composed from other objects).

In xUnit.net you'd typically address that problem with custom IEqualityComparers. This is more verbose, but also strikes me as more reusable. One disadvantage of that approach, however, is that when tests fail, the assertion message is typically useless.

This is the reason I favour Unquote: Instead of inventing a Boolean algebra(?) from scratch, it uses the existing language and still gives you good error messages. Alas, that only works in F#.

In general, though, I'm inclined to think that all of these APIs address symptoms rather than solve real problems. Granted, they're useful whenever you need to make assertions against values that you don't control, but for your own APIs, a simpler solution is to model values as immutable data with structural equality.

Another question is whether aiming for clear assertion messages is optimising for the right concern. At least with TDD, I don't think that it is.

Agilean

There are other agile methodologies than scrum.

More than twenty years after the Agile Manifesto it looks as though there's only one kind of agile process left: Scrum.

I recently held a workshop and as a side remark I mentioned that I don't consider scrum the best development process. This surprised some attendees, who politely inquired about my reasoning.

My experience with scrum #

The first nine years I worked as a professional programmer, the companies I worked in used various waterfall processes. When I joined the Microsoft Dynamics Mobile team in 2008 they were already using scrum. That was my first exposure to it, and I liked it. Looking back on it today, we weren't particular dogmatic about the process, being more interested in getting things done.

One telling fact is that we took turns being Scrum Master. Every sprint we'd rotate that role.

We did test-driven development, and had two-week sprints. This being a Microsoft development organisation, we had a dedicated build master, tech writers, specialised testers, and security reviews.

I liked it. It's easily one of the most professional software organisations I've worked in. I think it was a good place to work for many reasons. Scrum may have been a contributing factor, but hardly the only reason.

I have no issues with scrum as we practised it then. I recall later attending a presentation by Mike Cohn where he outlined four quadrants of team maturity. You'd start with scrum, but use retrospectives to evaluate what worked and what didn't. Then you'd adjust. A mature, self-organising team would arrive at its own process, perhaps initiated with scrum, but now having little resemblance with it.

I like scrum when viewed like that. When it becomes rigid and empty ceremony, I don't. If all you do is daily stand-ups, sprints, and backlogs, you may be doing scrum, but probably not agile.

Continuous deployment #

After Microsoft I joined a startup so small that formal process was unnecessary. Around that time I also became interested in lean software development. In the beginning, I learned a lot from Martin Jul who seemed to use the now-defunct Ative blog as a public notepad as he was reading works of Deming. I suppose, if you want a more canonical introduction to the topic, that you might start with one of the Poppendiecks' books, but since I've only read Implementing Lean Software Development, that's the only one I can recommend.

Around 2014 I returned to a regular customer. The team had, in my absence, been busy implementing continuous deployment. Instead of artificial periods like 'sprints' we had a kanban board to keep track of our work. We used a variation of feature flags and marked features as done when they were complete and in production.

Why wait until next Friday if the feature is done, done on a Wednesday? Why wait until the next Monday to identify what to work on next, if you're ready to take on new work on a Thursday? Why not move towards one-piece flow?

An effective self-organising team typically already knows what it's doing. Much process is introduced in order to give external stakeholders visibility into what a team is doing.

I found, in that organisation, that continuous deployment eliminated most of that need. At one time I asked a stakeholder what he thought of the feature I'd deployed a week before - a feature that he had requested. He replied that he hadn't had time to look at it yet.

The usual inquires about status (Is it done yet? When is it done?) were gone. The team moved faster than the stakeholders could keep up. That also gave us enough slack to keep the code base in good order. We also used test-driven development throughout (TDD).

TDD with continuous deployment and a kanban board strikes me as congenial with the ideas of lean software development, but that's not all.

Stop-the-line issues #

An andon cord is a central concept in lean manufactoring. If a worker (or anyone, really) discovers a problem during production, he or she pulls the andon cord and stops the production line. Then everyone investigates and determines what to do about the problem. Errors are not allowed to accumulate.

I think that I've internalised this notion to such a degree that I only recently connected it to lean software development.

In Code That Fits in Your Head, I recommend turning compiler warnings into errors at the beginning of a code base. Don't allow warnings to pile up. Do the same with static code analysis and linters.

When discussing software engineering with developers, I'm beginning to realise that this runs even deeper.

- Turn warnings into errors. Don't allow warnings to accumulate.

- The correct number of unhandled exceptions in production is zero. If you observe an unhandled exception in your production logs, fix it. Don't let them accumulate.

- The correct number of known bugs is zero. Don't let bugs accumulate.

If you're used to working on a code base with hundreds of known bugs, and frequent exceptions in production, this may sound unrealistic. If you deal with issues as soon as they arise, however, this is not only possible - it's faster.

In lean software development, bugs are stop-the-line issues. When something unexpected happens, you stop what you're doing and make fixing the problem the top priority. You build quality in.

This has been my modus operandi for years, but I only recently connected the dots to realise that this is a typical lean practice. I may have picked it up from there. Or perhaps it's just common sense.

Conclusion #

When Agile was new and exciting, there were extreme programming and scrum, and possibly some lesser known techniques. Lean was around the corner, but didn't come to my attention, at least, until around 2010. Then it seems to have faded away again.

Today, agile looks synonymous with scrum, but I find lean software development more efficient. Why divide work into artificial time periods when you can release continuously? Why plan bug fixing when it's more efficient to stop the line and deal with the problem as it arises?

That may sound counter-intuitive, but it works because it prevents technical debt from accumulating.

Lean software development is, in my experience, a better agile methodology than scrum.

In the long run

Software design decisions should be time-aware.

A common criticism of modern capitalism is that maximising shareholder value leads to various detrimental outcomes, both societal, but possibly also for the maximising organisation itself. One major problem is when company leadership is incentivised to optimise stock market price for the next quarter, or other short terms. When considering only the short term, decision makers may (rationally) decide to sacrifice long-term benefits for short-term gains.

We often see similar behaviour in democracies. Politicians tend to optimise within a time frame that coincides with the election period. Getting re-elected is more important than good policy in the next period.

These observations are crude generalisations. Some democratic politicians and CEOs take longer views. Inherent in the context, however, is an incentive to short-term thinking.

This, it strikes me, is frequently the case in software development.

Particularly in the context of scrum there's a focus on delivering at the end of every sprint. I've observed developers and other stakeholders together engage in short-term thinking in order to meet those arbitrary and fictitious deadlines.

Even when deadlines are more remote than two weeks, project members rarely think beyond some perceived end date. As I describe in Code That Fits in Your Head, a project is rarely is good way to organise software development work. Projects end. Successful software doesn't.

Regardless of the specific circumstances, a too myopic focus on near-term goals gives you an incentive to cut corners. To not care about code quality.

...we're all dead #

As Keynes once quipped:

"In the long run we are all dead."

Clearly, while you can be too short-sighted, you can also take too long a view. Sometimes deadlines matter, and software not used makes no-one happy.

Working software remains the ultimate test of value, but as I've tried to express many times before, this does not imply that anything else is worthless.

You can't measure code quality. Code quality isn't software quality. Low code quality slows you down, and that, eventually, costs you money, blood, sweat, and tears.

This is, however, not difficult to predict. All it takes is a slightly wider time horizon. Consider the impact of your decisions past the next deadline.

Conclusion #

Don't be too short-sighted, but don't forget the immediate value of what you do. Your decisions matter. The impact is not always immediate. Consider what consequences short-term optimisations may have in a longer perspective.

The IO monad

The IO container forms a monad. An article for object-oriented programmers.

This article is an instalment in an article series about monads. A previous article described the IO functor. As is the case with many (but not all) functors, this one also forms a monad.

SelectMany #

A monad must define either a bind or join function. In C#, monadic bind is called SelectMany. In a recent article, I gave an example of what IO might look like in C#. Notice that it already comes with a SelectMany function:

public IO<TResult> SelectMany<TResult>(Func<T, IO<TResult>> selector)

Unlike other monads, the IO implementation is considered a black box, but if you're interested in a prototypical implementation, I already posted a sketch in 2020.

Query syntax #

I have also, already, demonstrated syntactic sugar for IO. In that article, however, I used an implementation of the required SelectMany overload that is more explicit than it has to be. The monad introduction makes the prediction that you can always implement that overload in the same way, and yet here I didn't.

That's an oversight on my part. You can implement it like this instead:

public static IO<TResult> SelectMany<T, U, TResult>( this IO<T> source, Func<T, IO<U>> k, Func<T, U, TResult> s) { return source.SelectMany(x => k(x).Select(y => s(x, y))); }

Indeed, the conjecture from the introduction still holds.

Join #

In the introduction you learned that if you have a Flatten or Join function, you can implement SelectMany, and the other way around. Since we've already defined SelectMany for IO<T>, we can use that to implement Join. In this article I use the name Join rather than Flatten. This is an arbitrary choice that doesn't impact behaviour. Perhaps you find it confusing that I'm inconsistent, but I do it in order to demonstrate that the behaviour is the same even if the name is different.

The concept of a monad is universal, but the names used to describe its components differ from language to language. What C# calls SelectMany, Scala calls flatMap, and what Haskell calls join, other languages may call Flatten.

You can always implement Join by using SelectMany with the identity function:

public static IO<T> Join<T>(this IO<IO<T>> source) { return source.SelectMany(x => x); }

In C# the identity function is idiomatically given as the lambda expression x => x since C# doesn't come with a built-in identity function.

Return #

Apart from monadic bind, a monad must also define a way to put a normal value into the monad. Conceptually, I call this function return (because that's the name that Haskell uses). In the IO functor article, I wrote that the IO<T> constructor corresponds to return. That's not strictly true, though, since the constructor takes a Func<T> and not a T.

This issue is, however, trivially addressed:

public static IO<T> Return<T>(T x) { return new IO<T>(() => x); }

Take the value x and wrap it in a lazily-evaluated function.

Laws #

While IO values are referentially transparent you can't compare them. You also can't 'run' them by other means than running a program. This makes it hard to talk meaningfully about the monad laws.

For example, the left identity law is:

return >=> h ≡ h

Note the implied equality. The composition of return and h should be equal to h, for some reasonable definition of equality. How do we define that?

Somehow we must imagine that two alternative compositions would produce the same observable effects ceteris paribus. If you somehow imagine that you have two parallel universes, one with one composition (say return >=> h) and one with another (h), if all else in those two universes were equal, then you would observe no difference in behaviour.

That may be useful as a thought experiment, but isn't particularly practical. Unfortunately, due to side effects, things do change when non-deterministic behaviour and side effects are involved. As a simple example, consider an IO action that gets the current time and prints it to the console. That involves both non-determinism and a side effect.

In Haskell, that's a straightforward composition of two IO actions:

> h () = getCurrentTime >>= print

How do we compare two compositions? By running them?

> return () >>= h 2022-06-25 16:47:30.6540847 UTC > h () 2022-06-25 16:47:37.5281265 UTC

The outputs are not the same, because time goes by. Can we thereby conclude that the monad laws don't hold for IO? Not quite.

The IO Container is referentially transparent, but evaluation isn't. Thus, we have to pretend that two alternatives will lead to the same evaluation behaviour, all things being equal.

This property seems to hold for both the identity and associativity laws. Whether or not you compose with return, or in which evaluation order you compose actions, it doesn't affect the outcome.

For completeness sake, the C# implementation sketch is just a wrapper over a Func<T>. We can also think of such a function as a function from unit to T - in pseudo-C# () => T. That's a function; in other words: The Reader monad. We already know that the Reader monad obeys the monad laws, so the C# implementation, at least, should be okay.

Conclusion #

IO forms a monad, among other abstractions. This is what enables Haskell programmers to compose an arbitrary number of impure actions with monadic bind without ever having to force evaluation. In C# it might have looked the same, except that it doesn't.

Next: Test Data Generator monad.

Adding NuGet packages when offline

A fairly trivial technical detective story.

I was recently in an air plane, writing code, when I realised that I needed to add a couple of NuGet packages to my code base. I was on one of those less-travelled flights in Europe, on board an Embraer E190, and as is usually the case on those 1½-hour flights, there was no WiFi.

Adding a NuGet package typically requires that you're online so that the tools can query the relevant NuGet repository. You'll need to download the package, so if you're offline, you're just out of luck, right?

Fortunately, I'd previously used the packages I needed in other projects, on the same laptop. While I'm no fan of package restore, I know that the local NuGet tools cache packages somewhere on the local machine.

So, perhaps I could entice the tools to reuse a cached package...

First, I simply tried adding a package that I needed:

$ dotnet add package unquote Determining projects to restore... Writing C:\Users\mark\AppData\Local\Temp\tmpF3C.tmp info : X.509 certificate chain validation will use the default trust store selected by .NET. info : Adding PackageReference for package 'unquote' into project '[redacted]'. error: Unable to load the service index for source https://api.nuget.org/v3/index.json. error: No such host is known. (api.nuget.org:443) error: No such host is known.

Fine plan, but no success.

Clearly the dotnet tool was trying to access api.nuget.org, which, obviously, couldn't be reached because my laptop was in flight mode. It occurred to me, though, that the reason that the tool was querying api.nuget.org was that it wanted to see which version of the package was the most recent. After all, I hadn't specified a version.

What if I were to specify a version? Would the tool use the cached version of the package?

That seemed worth a try, but which versions did I already have on my laptop?

I don't go around remembering which version numbers I've used of various NuGet packages, but I expected the NuGet tooling to have that information available, somewhere.

But where? Keep in mind that I was offline, so couldn't easily look this up.

On the other hand, I knew that these days, most Windows applications keep data of that kind somewhere in AppData, so I started spelunking around there, looking for something that might be promising.

After looking around a bit, I found a subdirectory named AppData\Local\NuGet\v3-cache. This directory contained a handful of subdirectories obviously named with GUIDs. Each of these contained a multitude of .dat files. The names of those files, however, looked promising:

list_antlr_index.dat list_autofac.dat list_autofac.extensions.dependencyinjection.dat list_autofixture.automoq.dat list_autofixture.automoq_index.dat list_autofixture.automoq_range_2.0.0-3.6.7.dat list_autofixture.automoq_range_3.30.3-3.50.5.dat list_autofixture.automoq_range_3.50.6-4.17.0.dat list_autofixture.automoq_range_3.6.8-3.30.2.dat list_autofixture.dat ...

and so on.

These names were clearly(?) named list_[package-name].dat or list_[package-name]_index.dat, so I started looking around for one named after the package I was looking for (Unquote).

Often, both files are present, which was also the case for Unquote.

$ ls list_unquote* -l -rw-r--r-- 1 mark 197609 348 Oct 1 18:38 list_unquote.dat -rw-r--r-- 1 mark 197609 42167 Sep 23 21:29 list_unquote_index.dat

As you can tell, list_unquote_index.dat is much larger than list_unquote.dat. Since I didn't know what the format of these files were, I decided to look at the smallest one first. It had this content:

{

"versions": [

"1.3.0",

"2.0.0",

"2.0.1",

"2.0.2",

"2.0.3",

"2.1.0",

"2.1.1",

"2.2.0",

"2.2.1",

"2.2.2",

"3.0.0",

"3.1.0",

"3.1.1",

"3.1.2",

"3.2.0",

"4.0.0",

"5.0.0",

"6.0.0-rc.1",

"6.0.0-rc.2",

"6.0.0-rc.3",

"6.0.0",

"6.1.0"

]

}

A list of versions. Sterling. It looked as though version 6.1.0 was the most recent one on my machine, so I tried to add that one to my code base:

$ dotnet add package unquote --version 6.1.0 Determining projects to restore... Writing C:\Users\mark\AppData\Local\Temp\tmp815D.tmp info : X.509 certificate chain validation will use the default trust store selected by .NET. info : Adding PackageReference for package 'unquote' into project '[redacted]'. info : Restoring packages for [redacted]... info : Package 'unquote' is compatible with all the specified frameworks in project '[redacted]'. info : PackageReference for package 'unquote' version '6.1.0' added to file '[redacted]'. info : Generating MSBuild file [redacted]. info : Writing assets file to disk. Path: [redacted] log : Restored [redacted] (in 397 ms).

Jolly good! That worked.

This way I managed to install all the NuGet packages I needed. This was fortunate, because I had so little time to transfer to my connecting flight that I never got to open the laptop before I was airborne again - in another E190 without WiFi, and another session of offline programming.

Comments

A postscript to your detective story might note that the primary NuGet cache lives at %userprofile%\.nuget\packages on Windows and ~/.nuget/packages on Mac and Linux. The folder names there are much easier to decipher than the folders and files in the http cache.

Functors as invariant functors

A most likely useless set of invariant functors that nonetheless exist.

This article is part of a series of articles about invariant functors. An invariant functor is a functor that is neither covariant nor contravariant. See the series introduction for more details.

It turns out that all functors are also invariant functors.

Is this useful? Let me be honest and say that if it is, I'm not aware of it. Thus, if you're interested in practical applications, you can stop reading here. This article contains nothing of practical use - as far as I can tell.

Because it's there #

Why describe something of no practical use?

Why do some people climb Mount Everest? Because it's there, or for other irrational reasons. Which is fine. I've no personal goals that involve climbing mountains, but I happily engage in other irrational and subjective activities.

One of them, apparently, is to write articles of software constructs of no practical use, because it's there.

All functors are also invariant functors, even if that's of no practical use. That's just the way it is. This article explains how, and shows a few (useless) examples.

I'll start with a few Haskell examples and then move on to showing the equivalent examples in C#. If you're unfamiliar with Haskell, you can skip that section.

Haskell package #

For Haskell you can find an existing definition and implementations in the invariant package. It already makes most common functors Invariant instances, including [] (list), Maybe, and Either. Here's an example of using invmap with a small list:

ghci> invmap secondsToNominalDiffTime nominalDiffTimeToSeconds [0.1, 60] [0.1s,60s]

Here I'm using the time package to convert fixed-point decimals into NominalDiffTime values.

How is this different from normal functor mapping with fmap? In observable behaviour, it's not:

ghci> fmap secondsToNominalDiffTime [0.1, 60] [0.1s,60s]

When invariantly mapping a functor, only the covariant mapping function a -> b is used. Here, that's secondsToNominalDiffTime. The contravariant mapping function b -> a (nominalDiffTimeToSeconds) is simply ignored.

While the invariant package already defines certain common functors as Invariant instances, every Functor instance can be converted to an Invariant instance. There are two ways to do that: invmapFunctor and WrappedFunctor.

In order to demonstrate, we need a custom Functor instance. This one should do:

data Pair a = Pair (a, a) deriving (Eq, Show, Functor)

If you just want to perform an ad-hoc invariant mapping, you can use invmapFunctor:

ghci> invmapFunctor secondsToNominalDiffTime nominalDiffTimeToSeconds $ Pair (0.1, 60) Pair (0.1s,60s)

I can't think of any reason to do this, but it's possible.

WrappedFunctor is perhaps marginally more relevant. If you run into a function that takes an Invariant argument, you can convert any Functor to an Invariant instance by wrapping it in WrappedFunctor:

ghci> invmap secondsToNominalDiffTime nominalDiffTimeToSeconds $ WrapFunctor $ Pair (0.1, 60)

WrapFunctor {unwrapFunctor = Pair (0.1s,60s)}

A realistic, useful example still escapes me, but there it is.

Pair as an invariant functor in C# #

What would the above Haskell example look like in C#? First, we're going to need a Pair data structure:

public sealed class Pair<T> { public Pair(T x, T y) { X = x; Y = y; } public T X { get; } public T Y { get; } // More members follow...

Making Pair<T> a functor is so easy that Haskell can do it automatically with the DeriveFunctor extension. In C# you must explicitly write the function:

public Pair<T1> Select<T1>(Func<T, T1> selector) { return new Pair<T1>(selector(X), selector(Y)); }

An example equivalent to the above fmap example might be this, here expressed as a unit test:

[Fact] public void FunctorExample() { Pair<long> sut = new Pair<long>( TimeSpan.TicksPerSecond / 10, TimeSpan.TicksPerSecond * 60); Pair<TimeSpan> actual = sut.Select(ticks => new TimeSpan(ticks)); Assert.Equal( new Pair<TimeSpan>( TimeSpan.FromSeconds(.1), TimeSpan.FromSeconds(60)), actual); }

You can trivially make Pair<T> an invariant functor by giving it a function equivalent to invmap. As I outlined in the introduction it's possible to add an InvMap method to the class, but it might be more idiomatic to instead add a Select overload:

public Pair<T1> Select<T1>(Func<T, T1> tToT1, Func<T1, T> t1ToT) { return Select(tToT1); }

Notice that this overload simply ignores the t1ToT argument and delegates to the normal Select overload. That's consistent with the Haskell package. This unit test shows an examples:

[Fact] public void InvariantFunctorExample() { Pair<long> sut = new Pair<long>( TimeSpan.TicksPerSecond / 10, TimeSpan.TicksPerSecond * 60); Pair<TimeSpan> actual = sut.Select(ticks => new TimeSpan(ticks), ts => ts.Ticks); Assert.Equal( new Pair<TimeSpan>( TimeSpan.FromSeconds(.1), TimeSpan.FromSeconds(60)), actual); }

I can't think of a reason to do this in C#. In Haskell, at least, you have enough power of abstraction to describe something as simply an Invariant functor, and then let client code decide whether to use Maybe, [], Endo, or a custom type like Pair. You can't do that in C#, so the abstraction is even less useful here.

Conclusion #

All functors are invariant functors. You simply use the normal functor mapping function (fmap in Haskell, map in many other languages, Select in C#). This enables you to add an invariant mapping (invmap) that only uses the covariant argument (a -> b) and ignores the contravariant argument (b -> a).

Invariant functors are, however, not particularly useful, so neither is this result. Still, it's there, so deserves a mention. The situation is similar for the next article.

Error-accumulating composable assertions in C#

Perhaps the list monoid is all you need for non-short-circuiting assertions.

This article is the second instalment in a small articles series about applicative assertions. It explores a way to compose assertions in such a way that failure messages accumulate rather than short-circuit. It assumes that you've read the article series introduction and the previous article.

Unsurprisingly, the previous article showed that you can use an applicative functor to create composable assertions that don't short-circuit. It also concluded that, in C# at least, the API is awkward.

This article explores a simpler API.

A clue left by the proof of concept #

The previous article's proof of concept left a clue suggesting a simpler API. Consider, again, how the rather horrible RunAssertions method decides whether or not to throw an exception:

string errors = composition.Match( onFailure: f => string.Join(Environment.NewLine, f), onSuccess: _ => string.Empty); if (!string.IsNullOrEmpty(errors)) throw new Exception(errors);

Even though Validated<F, S> is a sum type, the RunAssertions method declines to take advantage of that. Instead, it reduces composition to a simple type: A string. It then decides to throw an exception if the errors value is not null or empty.

This suggests that using a sum type may not be necessary to distinguish between the success and the failure case. Rather, an empty error string is all it takes to indicate success.

Non-empty errors #

The proof-of-concept assertion type is currently defined as Validated with a particular combination of type arguments: Validated<IReadOnlyCollection<string>, Unit>. Consider, again, this Match expression:

string errors = composition.Match( onFailure: f => string.Join(Environment.NewLine, f), onSuccess: _ => string.Empty);

Does an empty string unambiguously indicate success? Or is it possible to arrive at an empty string even if composition actually represents a failure case?

You can arrive at an empty string from a failure case if the collection of error messages is empty. Consider the type argument that takes the place of the F generic type: IReadOnlyCollection<string>. A collection of this type can be empty, which would also cause the above Match to produce an empty string.

Even so, the proof-of-concept works in practice. The reason it works is that failure cases will never have empty assertion messages. We know this because (in the proof-of-concept code) only two functions produce assertions, and they each populate the error message collection with a string. You may want to revisit the AssertTrue and AssertEqual functions in the previous article to convince yourself that this is true.

This is a good example of knowledge that 'we' as developers know, but the code currently doesn't capture. Having to deal with such knowledge taxes your working memory, so why not encapsulate such information in the type itself?

How do you encapsulate the knowledge that a collection is never empty? Introduce a NotEmptyCollection collection. I'll reuse the class from the article Semigroups accumulate and add a Concat instance method:

public NotEmptyCollection<T> Concat(NotEmptyCollection<T> other) { return new NotEmptyCollection<T>(Head, Tail.Concat(other).ToArray()); }

Since the two assertion-producing functions both supply an error message in the failure case, it's trivial to change them to return Validated<NotEmptyCollection<string>, Unit> - just change the types used:

public static Validated<NotEmptyCollection<string>, Unit> AssertTrue( this bool condition, string message) { return condition ? Succeed<NotEmptyCollection<string>, Unit>(Unit.Value) : Fail<NotEmptyCollection<string>, Unit>(new NotEmptyCollection<string>(message)); } public static Validated<NotEmptyCollection<string>, Unit> AssertEqual<T>( T expected, T actual) { return Equals(expected, actual) ? Succeed<NotEmptyCollection<string>, Unit>(Unit.Value) : Fail<NotEmptyCollection<string>, Unit>( new NotEmptyCollection<string>($"Expected {expected}, but got {actual}.")); }

This change guarantees that the RunAssertions method only produces an empty errors string in success cases.

Error collection isomorphism #

Assertions are still defined by the Validated sum type, but the success case carries no information: Validated<NotEmptyCollection<T>, Unit>, and the failure case is always guaranteed to contain at least one error message.

This suggests that a simpler representation is possible: One that uses a normal collection of errors, and where an empty collection indicates an absence of errors:

public class Asserted<T> { public Asserted() : this(Array.Empty<T>()) { } public Asserted(T error) : this(new[] { error }) { } public Asserted(IReadOnlyCollection<T> errors) { Errors = errors; } public Asserted<T> And(Asserted<T> other) { if (other is null) throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(other)); return new Asserted<T>(Errors.Concat(other.Errors).ToList()); } public IReadOnlyCollection<T> Errors { get; } }

The Asserted<T> class is scarcely more than a glorified wrapper around a normal collection, but it's isomorphic to Validated<NotEmptyCollection<T>, Unit>, which the following two functions prove:

public static Asserted<T> FromValidated<T>(this Validated<NotEmptyCollection<T>, Unit> v) { return v.Match( failures => new Asserted<T>(failures), _ => new Asserted<T>()); } public static Validated<NotEmptyCollection<T>, Unit> ToValidated<T>(this Asserted<T> a) { if (a.Errors.Any()) { var errors = new NotEmptyCollection<T>( a.Errors.First(), a.Errors.Skip(1).ToArray()); return Validated.Fail<NotEmptyCollection<T>, Unit>(errors); } else return Validated.Succeed<NotEmptyCollection<T>, Unit>(Unit.Value); }

You can translate back and forth between Validated<NotEmptyCollection<T>, Unit> and Asserted<T> without loss of information.

A collection, however, gives rise to a monoid, which suggests a much simpler way to compose assertions than using an applicative functor.

Asserted truth #

You can now rewrite the assertion-producing functions to return Asserted<string> instead of Validated<NotEmptyCollection<string>, Unit>.

public static Asserted<string> True(bool condition, string message) { return condition ? new Asserted<string>() : new Asserted<string>(message); }

This Asserted.True function returns no error messages when condition is true, but a collection with the single element message when it's false.

You can use it in a unit test like this:

var assertResponse = Asserted.True( deleteResp.IsSuccessStatusCode, $"Actual status code: {deleteResp.StatusCode}.");

You'll see how assertResponse composes with another assertion later in this article. The example continues from the previous article. It's the same test from the same code base.

Asserted equality #

You can also rewrite the other assertion-producing function in the same way:

public static Asserted<string> Equal(object expected, object actual) { if (Equals(expected, actual)) return new Asserted<string>(); return new Asserted<string>($"Expected {expected}, but got {actual}."); }

Again, when the assertion passes, it returns no errors; otherwise, it returns a collection with a single error message.

Using it may look like this:

var getResp = await api.CreateClient().GetAsync(address); var assertState = Asserted.Equal(HttpStatusCode.NotFound, getResp.StatusCode);

At this point, each of the assertions are objects that represent a verification step. By themselves, they neither pass nor fail the test. You have to execute them to reach a verdict.

Evaluating assertions #

The above code listing of the Asserted<T> class already shows how to combine two Asserted<T> objects into one. The And instance method is a binary operation that, together with the parameterless constructor, makes Asserted<T> a monoid.

Once you've combined all assertions into a single Asserted<T> object, you need to Run it to produce a test outcome:

public static void Run(this Asserted<string> assertions) { if (assertions?.Errors.Any() ?? false) { var messages = string.Join(Environment.NewLine, assertions.Errors); throw new Exception(messages); } }

If there are no errors, Run does nothing; otherwise it combines all the error messages together and throws an exception. As was also the case in the previous article, I've allowed myself a few proof-of-concept shortcuts. The framework design guidelines admonishes against throwing System.Exception. It might be more appropriate to introduce a new Exception type that also allows enumerating the error messages.

The entire assertion phase of the test looks like this:

var assertResponse = Asserted.True( deleteResp.IsSuccessStatusCode, $"Actual status code: {deleteResp.StatusCode}."); var getResp = await api.CreateClient().GetAsync(address); var assertState = Asserted.Equal(HttpStatusCode.NotFound, getResp.StatusCode); assertResponse.And(assertState).Run();

You can see the entire test in the previous article. Notice how the two assertion objects are first combined into one with the And binary operation. The result is a single Asserted<string> object on which you can call Run.

Like the previous proof of concept, this assertion passes and fails in the same way. It's possible to compose assertions and collect error messages, instead of short-circuiting on the first failure, even without an applicative functor.

Method chaining #

If you don't like to come up with variable names just to make assertions, it's also possible to use the Asserted API's fluent interface:

var getResp = await api.CreateClient().GetAsync(address); Asserted .True( deleteResp.IsSuccessStatusCode, $"Actual status code: {deleteResp.StatusCode}.") .And(Asserted.Equal(HttpStatusCode.NotFound, getResp.StatusCode)) .Run();

This isn't necessarily better, but it's an option.

Conclusion #

While it's possible to design non-short-circuiting composable assertions using an applicative functor, it looks as though a simpler solution might solve the same problem. Collect error messages. If none were collected, interpret that as a success.

As I wrote in the introduction article, however, this may not be the last word. Some assertions return values that can be used for other assertions. That's a scenario that I have not yet investigated in this light, and it may change the conclusion. If so, I'll add more articles to this small article series. As I'm writing this, though, I have no such plans.

Did I just, in a roundabout way, write that more research is needed?

Comments

I think NUnit's Assert.Multiple is worth mentioning in this series. It does not require any complicated APIs, just wrap your existing test with multiple asserts into a delegate.

Pavel, thank you for writing. I'm aware of both that API and similar ones for other testing frameworks. As is usually the case, there are trade-offs to consider. I'm currently working on some material that may turn into another article about that.

A new article is now available: Built-in alternatives to applicative assertions.

When do tests fail?

Optimise for the common scenario.

Unit tests occasionally fail. When does that happen? How often? What triggers it? What information is important when tests fail?

Regularly I encounter the viewpoint that it should be easy to understand the purpose of a test when it fails. Some people consider test names important, a topic that I've previously discussed. Recently I discussed the Assertion Roulette test smell on Twitter, and again I learned some surprising things about what people value in unit tests.

The importance of clear assertion messages #

The Assertion Roulette test smell is often simplified to degeneracy, but it really describes situations where it may be a problem if you can't tell which of several assertions actually caused a test to fail.

Josh McKinney gave a more detailed example than Gerard Meszaros does in the book:

"Background. In a legacy product, we saw some tests start failing intermittently. They weren’t just flakey, but also failed without providing enough info to fix. One of things which caused time to fix to increase was multiple ways of a single test to fail."

He goes on:

"I.e. if you fix the first assertion and you know there still could be flakiness, or long cycle times to see the failure. Multiple assertions makes any test problem worse. In an ideal state, they are fine, but every assertion doubles the amount of failures a test catches."

and concludes:

"the other main way (unrelated) was things like:

assertTrue(someListResult.isRmpty())

Which tells you what failed, but nothing about how.

But the following is worse. You must run the test twice to fix:

assertFalse(someList.isEmpty());

assertEqual(expected, list.get(0));"

The final point is due to the short-circuiting nature of most assertion libraries. That, however, is a solvable problem.

I find the above a compelling example of why Assertion Roulette may be problematic.

It did give me pause, though. How common is this scenario?

Out of the blue #

The situation described by Josh McKinney comes with more than a single warning flag. I hope that it's okay to point some of them out. I didn't get the impression from my interaction with Josh McKinney that he considered the situation ideal in any way.

First, of course, there's the lack of information about the problem. Here, that's a real problem. As I understand it, it makes it harder to reproduce the problem in a development environment.

Next, there's long cycle times, which I interpret as significant time may pass from when you attempt a fix until you can actually observe whether or not it worked. Josh McKinney doesn't say how long, but I wouldn't surprised if it was measured in days. At least, if the cycle time is measured in days, I can see how this is a problem.

Finally, there's the observation that "some tests start failing intermittently". This was the remark that caught my attention. How often does that happen?

Tests shouldn't do that. Tests should be deterministic. If they're not, you should work to eradicate non-determinism in tests.

I'll be the first to admit that that I also write non-deterministic tests. Not by design, but because I make mistakes. I've written many Erratic Tests in my career, and I've documented a few of them here:

- Waiting to happen

- Waiting to never happen

- Fortunately, I don't squash my commits

- Make pre-conditions explicit in Property-Based Tests

While it can happen, it shouldn't be the norm. When it nonetheless happens, eradicating that source of non-determinism should be top priority. Pull the andon cord.

When tests fail #

Ideally, tests should rarely fail. As examined above, you may have Erratic Tests in your test suite, and if you do, these tests will occasionally (or often) fail. As Martin Fowler writes, this is a problem and you should do something about it. He also outlines strategies for it.

Once you've eradicated non-determinism in unit tests, then when do tests fail?

I can think of a couple of situations.

Tests routinely fail as part of the red-green-refactor cycle. This is by design. If no test is failing in the red phase, you probably made a mistake (which also regularly happens to me), or you may not really be doing test-driven development (TDD).

Another situation that may cause a test to fail is if you changed some code and triggered a regression test.

In both cases, tests don't just fail out of the blue. They fail as an immediate consequence of something you did.

Optimise for the common scenario #

In both cases you're (hopefully) in a tight feedback loop. If you're in a tight feedback loop, then how important is the assertion message really? How important is the test name?

You work on the code base, make some changes, run the tests. If one or more tests fail, it's correlated to the change you just made. You should have a good idea of what went wrong. Are code forensics and elaborate documentation really necessary to understand a test that failed because you just did something a few minutes before?

The reason I don't care much about test names or whether there's one or more assertion in a unit test is exactly that: When tests fail, it's usually because of something I just did. I don't need diagnostics tools to find the root cause. The root cause is the change that I just made.

That's my common scenario, and I try to optimise my processes for the common scenarios.

Fast feedback #

There's an implied way of working that affects such attitudes. Since I learned about TDD in 2003 I've always relished the fast feedback I get from a test suite. Since I tried continuous deployment around 2014, I consider it central to modern software engineering (and Accelerate strongly suggests so, too).

The modus operandi I outline above is one of fast feedback. If you're sitting on a feature branch for weeks before integrating into master, or if you can only deploy two times a year, this influences what works and what doesn't.

Both Modern Software Engineering and Accelerate make a strong case that short feedback cycles are pivotal for successful software development organisations.

I also understand that that's not the reality for everyone. When faced with long cycle times, a multitude of Erratic Tests, a legacy code base, and so on, other things become important. In those circumstances, tests may fail for different reasons.

When you work with TDD, continuous integration (CI), and continuous deployment (CD), then when do tests fail? They fail because you made them fail, only minutes earlier. Fix your code and move forward.

Conclusion #

When discussing test names and assertion messages, I've been surprised by the emphasis some people put on what I consider to be of secondary importance. I think the explanation is that circumstances differ.

With TDD and CI/CD you mostly look at a unit test when you write it, or if some regression test fails because you changed some code (perhaps in response to a test you just wrote). Your test suite may have hundreds or thousands of tests. Most of these pass every time you run the test suite. That's the normal state of affairs.

In other circumstances, you may have Erratic Tests that fail unpredictably. You should make it a priority to stop that, but as part of that process, you may need good assertion messages and good test names.

Different circumstances call for different reactions, so what works well in one situation may be a liability in other situations. I hope that this article has shed a little light on the forces you may want to consider.

Comments

First of all, let me thank you for taking time and effort to discuss this.

There's a minor point about integration testing:

The situation is somewhat more complicated: in fact, I tend to have at least a few integration tests for a feature I'm involved with, starting the coverage from the happy paths (the minimum requirement being to verify that we've wired correctly as many components as can be verified), and then, if possible, extending to error paths, edge cases and so on. Even the code from my email originally had integration tests covering all the outcomes for a single rendering (browser). The problem that I've faced then, and which prompted my question, was exactly the one that you quote from J.B. Rainsberger: combinatorial explosion. As soon as I decided to cover a second rendering (mobile), I saw that I needed to replicate the setups for outcomes (success/fail/missing), but modify the asserts for their rendering. And then again the same for the native client. Unit tests, even with their ungainly break in encapsulation, gave the simple appeal of writing less code...

Hopefully, this seem to be the very same premise that you explore towards the end of your post, leading to the property-based testing - which I was trying to incorporate into my toolset for quite some time, but was always somewhat baffled at how it should work and integrate into object-oriented (and C#-based) code. So I'm very much looking forward for your next installment in this series.

And again, thank you for exploring these matters.

Sergei, thank you for writing. I hope that this small series of articles will be able to at least give you some ideas. I am, however, concerned that I may miss the mark.

When discussing problems like this, there's always a risk that the examples we look at are too simple; that they don't adequately represent the real world. For instance, we may look at the example code in the next few articles and calculate how well we've covered all combinations.

Perhaps we may find that the combinatorial 'explosion' is only in the ten-thousands, which is within reasonable reach of well-written properties.