ploeh blog danish software design

Refactoring the TCP State pattern example to pure functions

A C# example.

This article is one of the examples that I promised in the earlier article The State pattern and the State monad. That article examines the relationship between the State design pattern and the State monad. That article is deliberately abstract, so one or more examples are in order.

In this article, I show you how to start with the example from Design Patterns and refactor it to an immutable solution using pure functions.

The code shown here is available on GitHub.

TCP connection #

The example is a class that handles TCP connections. The book's example is in C++, while I'll show my C# interpretation.

A TCP connection can be in one of several states, so the TcpConnection class keeps an instance of the polymorphic TcpState, which implements the state and transitions between them.

TcpConnection plays the role of the State pattern's Context, and TcpState of the State.

public class TcpConnection { public TcpState State { get; internal set; } public TcpConnection() { State = TcpClosed.Instance; } public void ActiveOpen() { State.ActiveOpen(this); } public void PassiveOpen() { State.PassiveOpen(this); } // More members that delegate to State follows...

The TcpConnection class' methods delegate to a corresponding method on TcpState, passing itself an argument. This gives the TcpState implementation an opportunity to change the TcpConnection's State property, which has an internal setter.

State #

This is the TcpState class:

public class TcpState { public virtual void Transmit(TcpConnection connection, TcpOctetStream stream) { } public virtual void ActiveOpen(TcpConnection connection) { } public virtual void PassiveOpen(TcpConnection connection) { } public virtual void Close(TcpConnection connection) { } public virtual void Synchronize(TcpConnection connection) { } public virtual void Acknowledge(TcpConnection connection) { } public virtual void Send(TcpConnection connection) { } }

I don't consider this entirely idiomatic C# code, but it seems closer to the book's C++ example. (It's been a couple of decades since I wrote C++, so I could be mistaken.) It doesn't matter in practice, but instead of a concrete class with no-op virtual methods, I would usually define an interface. I'll do that in the next example article.

The methods have the same names as the methods on TcpConnection, but the signatures are different. All the TcpState methods take a TcpConnection parameter, whereas the TcpConnection methods take no arguments.

While the TcpState methods don't do anything, various classes can inherit from the class and override some or all of them.

Connection closed #

The book shows implementations of three classes that inherit from TcpState, starting with TcpClosed. Here's my translation to C#:

public class TcpClosed : TcpState { public static TcpState Instance = new TcpClosed(); private TcpClosed() { } public override void ActiveOpen(TcpConnection connection) { // Send SYN, receive SYN, Ack, etc. connection.State = TcpEstablished.Instance; } public override void PassiveOpen(TcpConnection connection) { connection.State = TcpListen.Instance; } }

This implementation overrides ActiveOpen and PassiveOpen. In both cases, after performing some work, they change connection.State.

"

TCPStatesubclasses maintain no local state, so they can be shared, and only one instance of each is required. The unique instance ofTCPStatesubclass is obtained by the staticInstanceoperation. [...]"This make each

TCPStatesubclass a Singleton [...]."

I've maintained that property of each subclass in my C# code, even though it has no impact on the structure of the State pattern.

The other subclasses #

The next subclass, TcpEstablished, is cast in the same mould:

public class TcpEstablished : TcpState { public static TcpState Instance = new TcpEstablished(); private TcpEstablished() { } public override void Close(TcpConnection connection) { // send FIN, receive ACK of FIN connection.State = TcpListen.Instance; } public override void Transmit( TcpConnection connection, TcpOctetStream stream) { connection.ProcessOctet(stream); } }

As is TcpListen:

public class TcpListen : TcpState { public static TcpState Instance = new TcpListen(); private TcpListen() { } public override void Send(TcpConnection connection) { // Send SYN, receive SYN, ACK, etc. connection.State = TcpEstablished.Instance; } }

I admit that I find these examples a bit anaemic, since there's really no logic going on. None of the overrides change state conditionally, which would be possible and make the examples a little more interesting. If you're interested in an example where this happens, see my article Tennis kata using the State pattern.

Refactor to pure functions #

There's only one obvious source of impurity in the example: The literal State mutation of TcpConnection:

public TcpState State { get; internal set; }

While client code can't set the State property, subclasses can, and they do. After all, it's how the State pattern works.

It's quite a stretch to claim that if we can only get rid of that property setter then all else will be pure. After all, who knows what all those comments actually imply:

// Send SYN, receive SYN, ACK, etc.

To be honest, we must imagine that I/O takes place here. This means that even though it's possible to refactor away from mutating the State property, these implementations are not really going to be pure functions.

I could try to imagine what that SYN and ACK would look like, but it would be unfounded and hypothetical. I'm not going to do that here. Instead, that's the reason I'm going to publish a second article with a more realistic and complex example. When it comes to the present example, I'm going to proceed with the unreasonable assumption that the comments hide no nondeterministic behaviour or side effects.

As outlined in the article that compares the State pattern and the State monad, you can refactor state mutation to a pure function by instead returning the new state. Usually, you'd have to return a tuple, because you'd also need to return the 'original' return value. Here, however, the 'return type' of all methods is void, so this isn't necessary.

void is isomorphic to unit, so strictly speaking you could refactor to a return type like Tuple<Unit, TcpConnection>, but that is isomorphic to TcpConnection. (If you need to understand why that is, try writing two functions: One that converts a Tuple<Unit, TcpConnection> to a TcpConnection, and another that converts a TcpConnection to a Tuple<Unit, TcpConnection>.)

There's no reason to make things more complicated than they have to be, so I'm going to use the simplest representation: TcpConnection. Thus, you can get rid of the State mutation by instead returning a new TcpConnection from all methods:

public class TcpConnection { public TcpState State { get; } public TcpConnection() { State = TcpClosed.Instance; } private TcpConnection(TcpState state) { State = state; } public TcpConnection ActiveOpen() { return new TcpConnection(State.ActiveOpen(this)); } public TcpConnection PassiveOpen() { return new TcpConnection(State.PassiveOpen(this)); } // More members that delegate to State follows...

The State property no longer has a setter; there's only a public getter. In order to 'change' the state, code must return a new TcpConnection object with the new state. To facilitate that, you'll need to add a constructor overload that takes the new state as an input. Here I made it private, but making it more accessible is not prohibited.

This implies, however, that the TcpState methods also return values instead of mutating state. The base class now looks like this:

public class TcpState { public virtual TcpState Transmit(TcpConnection connection, TcpOctetStream stream) { return this; } public virtual TcpState ActiveOpen(TcpConnection connection) { return this; } public virtual TcpState PassiveOpen(TcpConnection connection) { return this; } // And so on...

Again, all the methods previously 'returned' void, so while, according to the State monad, you should strictly speaking return Tuple<Unit, TcpState>, this simplifies to TcpState.

Individual subclasses now do their work and return other TcpState implementations. I'm not going to tire you with all the example subclasses, so here's just TcpEstablished:

public class TcpEstablished : TcpState { public static TcpState Instance = new TcpEstablished(); private TcpEstablished() { } public override TcpState Close(TcpConnection connection) { // send FIN, receive ACK of FIN return TcpListen.Instance; } public override TcpState Transmit( TcpConnection connection, TcpOctetStream stream) { TcpConnection newConnection = connection.ProcessOctet(stream); return newConnection.State; } }

The trickiest implementation is Transmit, since ProcessOctet returns a TcpConnection while the Transmit method has to return a TcpState. Fortunately, the Transmit method can achieve that goal by returning newConnection.State. It feels a bit roundabout, but highlights a point I made in the previous article: The TcpConnection and TcpState classes are isomorphic - or, they would be if we made the TcpConnection constructor overload public. Thus, the TcpConnection class is redundant and might be deleted.

Conclusion #

This article shows how to refactor the TCP connection sample code from Design Patterns to pure functions.

If it feels as though something's missing there's a good reason for that. The example, as given, is degenerate because all methods 'return' void, and we don't really know what the actual implementation code (all that Send SYN, receive SYN, ACK, etc.) looks like. This means that we actually don't have to make use of the State monad, because we can get away with endomorphisms. All methods on TcpConnection are really functions that take TcpConnection as input (the instance itself) and return TcpConnection. If you want to see a more realistic example showcasing that perspective, see my article From State tennis to endomorphism.

Even though the example is degenerate, I wanted to show it because otherwise you might wonder how the book's example code fares when exposed to the State monad. To be clear, because of the nature of the example, the State monad never becomes necessary. Thus, we need a second example.

Next: Refactoring a saga from the State pattern to the State monad.

When to refactor

FAQ: How do I convince my manager to let me refactor?

This question frequently comes up. Developers want to refactor, but are under the impression that managers or other stakeholders will not let them.

Sometimes people ask me how to convince their managers to get permission to refactor. I can't answer that. I don't know how to convince other people. That's not my métier.

I also believe that professional programmers should make their own decisions. You don't ask permission to add three lines to a file, or create a new class. Why do you feel that you have to ask permission to refactor?

Does refactoring take time? #

In Code That Fits in Your Head I tell the following story:

"I once led an effort to refactor towards deeper insight. My colleague and I had identified that the key to implementing a new feature would require changing a fundamental class in our code base.

"While such an insight rarely arrives at an opportune time, we wanted to make the change, and our manager allowed it.

"A week later, our code still didn’t compile.

"I’d hoped that I could make the change to the class in question and then lean on the compiler to identify the call sites that needed modification. The problem was that there was an abundance of compilation errors, and fixing them wasn’t a simple question of search-and-replace.

"My manager finally took me aside to let me know that he wasn’t satisfied with the situation. I could only concur.

"After a mild dressing down, he allowed me to continue the work, and a few more days of heroic effort saw the work completed.

"That’s a failure I don’t intend to repeat."

There's a couple of points to this story. Yes, I did ask for permission before refactoring. I expected the process to take time, and I felt that making such a choice of prioritisation should involve my manager. While this manager trusted me, I felt a moral obligation to be transparent about the work I was doing. I didn't consider it professional to take a week out of the calendar and work on one thing while the rest of the organisation was expecting me to be working on something else.

So I can understand why developers feel that they have to ask permission to refactor. After all, refactoring takes time... Doesn't it?

Small steps #

This may unearth the underlying assumption that prevents developers from refactoring: The notion that refactoring takes time.

As I wrote in Code That Fits in Your Head, that was a failure I didn't intend to repeat. I've never again asked permission to refactor, because I've never since allowed myself to be in a situation where refactoring would take significant time.

The reason I tell the story in the book is that I use it to motivate using the Strangler pattern at the code level. The book proceeds to show an example of that.

Migrating code to a new API by allowing the old and the new to coexist for a while is only one of many techniques for taking smaller steps. Another is the use of feature flags, a technique that I also show in the book. Martin Fowler's Refactoring is literally an entire book about how to improve code bases in small, controlled steps.

Follow the red-green-refactor checklist and commit after each green and refactor step. Move in small steps and use Git tactically.

I'm beginning to realise, though, that moving in small steps is a skill that must be explicitly learned. This may seem obvious once posited, but it may also be helpful to explicitly state it.

Whenever I've had a chance to talk to other software professionals and thought leaders, they agree. As far as I can tell, universities and coding boot camps don't teach this skill, and if (like me) you're autodidact, you probably haven't learned it either. After all, few people insist that this is an important skill. It may, however, be one of the most important programming skills you can learn.

Make it work, then make it right #

When should you refactor? As the boy scout rule suggests: All the time.

You can, specifically, do it after implementing a new feature. As Kent Beck perhaps said or wrote: Make it work, then make it right.

How long does it take to make it right?

Perhaps you think that it takes as much time as it does to make it work.

Perhaps you think that making it right takes even more time.

If this is how much time making the code right takes, I can understand why you feel that you need to ask your manager. That's what I did, those many years ago. But what if the proportions are more like this?

Do you still feel that you need to ask for permission to refactor?

Writing code so that the team can keep a sustainable pace is your job. It's not something you should have to ask for permission to do.

"Any fool can write code that a computer can understand. Good programmers write code that humans can understand."

Making the code right is not always a huge endeavour. It can be, if you've already made a mess of it, but if it's in good condition, keeping it that way doesn't have to take much extra effort. It's part of the ongoing design process that programming is.

How do you know what right is? Doesn't this make-it-work-make-it-right mentality lead to speculative generality?

No-one expects you to be able to predict the future, so don't try. Making it right means making the code good in the current context. Use good names, remove duplication, get rid of code smells, keep methods small and complexity low. Refactor if you exceed a threshold.

Make code easy to change #

The purpose of keeping code in a good condition is to make future changes as easy as possible. If you can't predict the future, however, then how do you know how to factor the code?

Another Kent Beck aphorism suggests a tactic:

"for each desired change, make the change easy (warning: this may be hard), then make the easy change"

In other words, when you know what you need to accomplish, first refactor the code so that it becomes easier to achieve the goal, and only then write the code to do that.

Should you ask permission to refactor in such a case? Only if you sincerely believe that you can complete the entire task significantly faster without first improving the code. How likely is that? If the code base is already a mess, how easy is it to make changes? Not easy, and granted: That will also be true for refactoring. The difference between first refactoring and not refactoring, however, is that if you refactor, you leave the code in a better state. If you don't, you leave it in a worse state.

These decisions compound.

But what if, as Kent Beck implies, refactoring is hard? Then the situation might look like this:

Should you ask for permission to refactor? I don't think so. While refactoring in this diagram is most of the work, it makes the change easy. Thus, once you're done refactoring, you make the easy change. The total amount of time this takes may turn out to be quicker than if you hadn't refactored (compare this figure to the previous figure: they're to scale). You also leave the code base in a better state so that future changes may be easier.

Conclusion #

There are lots of opportunities for refactoring. Every time you see something that could be improved, why not improve it? The fact that you're already looking at a piece of code suggests that it's somehow relevant to your current task. If it takes ten, fifteen minutes to improve it, why not do it? What if it takes an hour?

Most people think nothing of spending hours in meetings without asking their managers. If this is true, you can also decide to use a couple of hours improving code. They're likely as well spent as the meeting hours.

The key, however, is to be able to perform opportunistic refactoring. You can't do that if you can only move in day-long iterations; if hours, or days, go by when you can't compile, or when most tests fail.

On the other hand, if you're able to incrementally improve the code base in one-minute, or fifteen-minute, steps, then you can improve the code base every time an occasion arrives.

This is a skill that you need to learn. You're not born with the ability to improve in small steps. You'll have to practice - for example by doing katas. One customer of mine told me that they found Kent Beck's TCR a great way to teach that skill.

You can refactor in small steps. It's part of software engineering. Usually, you don't need to ask for permission.

Coalescing DTOs

Refactoring to a universal abstraction.

Despite my best efforts, no code base I write is perfect. This is also true for the code base that accompanies Code That Fits in Your Head.

One (among several) warts that has annoyed me for long is this:

[HttpPost("restaurants/{restaurantId}/reservations")] public async Task<ActionResult> Post( int restaurantId, ReservationDto dto) { if (dto is null) throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(dto)); var id = dto.ParseId() ?? Guid.NewGuid(); Reservation? reservation = dto.Validate(id); if (reservation is null) return new BadRequestResult(); // More code follows...

Passing id to Validate annoys me. Why does Validate need an id?

When you see it in context, it may makes some sort of sense, but in isolation, it seems arbitrary:

internal Reservation? Validate(Guid id)

Why does the method need an id? Doesn't ReservationDto have an Id?

Abstraction, broken #

Yes, indeed, ReservationDto has an Id property:

public string? Id { get; set; }

Then why do callers have to pass an id argument? Doesn't Validate use the Id property? It's almost as though the Validate method begs you to read the implementing code:

internal Reservation? Validate(Guid id) { if (!DateTime.TryParse(At, out var d)) return null; if (Email is null) return null; if (Quantity < 1) return null; return new Reservation( id, d, new Email(Email), new Name(Name ?? ""), Quantity); }

Indeed, the method doesn't use the Id property. Reading the code may not be of much help, but at least we learn that id is passed to the Reservation constructor. It's still not clear why the method isn't trying to parse the Id property, like it's doing with At.

I'll return to the motivation in a moment, but first I'd like to dwell on the problems of this design.

It's a typical example of ad-hoc design. I had a set of behaviours I needed to implement, and in order to avoid code duplication, I came up with a method that seemed to solve the problem.

And indeed, the Validate method does solve the problem of code duplication. It also passes all tests. It could be worse.

It could also be better.

The problem with an ad-hoc design like this is that the motivation is unclear. As a reader, you feel that you're missing the full picture. Perhaps you feel compelled to read the implementation code to gain a better understanding. Perhaps you look for other call sites. Perhaps you search the Git history to find a helpful comment. Perhaps you ask a colleague.

It slows you down. Worst of all, it may leave you apprehensive of refactoring. If you feel that there's something you don't fully understand, you may decide to leave the API alone, instead of improving it.

It's one of the many ways that code slowly rots.

What's missing here is a proper abstraction.

Motivation #

I recently hit upon a design that I like better. Before I describe it, however, you need to understand the problem I was trying to solve.

The code base for the book is a restaurant reservation REST API, and I was evolving the code as I wrote it. I wanted the code base (and its Git history) to be as realistic as possible. In a real-world situation, you don't always know all requirements up front, or even if you do, they may change.

At one point I decided that a REST client could supply a GUID when making a new reservation. On the other hand, I had lots of existing tests (and a deployed system) that accepted reservations without IDs. In order to not break compatibility, I decided to use the ID if it was supplied with the DTO, and otherwise create one. (I later explored an API without explicit IDs, but that's a different story.)

The id is a JSON property, however, so there's no guarantee that it's properly formatted. Thus, the need to first parse it:

var id = dto.ParseId() ?? Guid.NewGuid();

To make matters even more complicated, when you PUT a reservation, the ID is actually part of the resource address, which means that even if it's present in the JSON document, that value should be ignored:

[HttpPut("restaurants/{restaurantId}/reservations/{id}")] public async Task<ActionResult> Put( int restaurantId, string id, ReservationDto dto) { if (dto is null) throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(dto)); if (!Guid.TryParse(id, out var rid)) return new NotFoundResult(); Reservation? reservation = dto.Validate(rid); if (reservation is null) return new BadRequestResult(); // More code follows...

Notice that this Put implementation exclusively considers the resource address id parameter. Recall that the Validate method ignores the dto's Id property.

This is knowledge about implementation details that leaks through to the calling code. As a client developer, you need to know and keep this knowledge in your head while you write your own code. That's not really code that fits in your head.

As I usually put it: If you have to read the code, it implies that encapsulation is broken.

At the time, however, I couldn't think of a better alternative, and since the problem is still fairly small and localised, I decided to move on. After all, perfect is the enemy of good.

Why don't you just..? #

Is there a better way? Perhaps you think that you've spotted an obvious improvement. Why don't I just try to parse dto.Id and then create a Guid.NewGuid() if parsing fails? Like this:

internal Reservation? Validate() { if (!Guid.TryParse(Id, out var id)) id = Guid.NewGuid(); if (!DateTime.TryParse(At, out var d)) return null; if (Email is null) return null; if (Quantity < 1) return null; return new Reservation( id, d, new Email(Email), new Name(Name ?? ""), Quantity); }

The short answer is: Because it doesn't work.

It may work for Get, but then Put doesn't have a way to tell the Validate method which ID to use.

Or rather: That's not entirely true, because this is possible:

dto.Id = id;

Reservation? reservation = dto.Validate();

This does suggest an even better way. Before we go there, however, there's another reason I don't like this particular variation: It makes Validate impure.

Why care? you may ask.

I always end up regretting making an otherwise potentially pure function non-deterministic. Sooner or later, it turns out to have been a bad decision, regardless of how alluring it initially looked. I recently gave an example of that.

When weighing the advantages and disadvantages, I preferred passing id explicitly rather than relying on Guid.NewGuid() inside Validate.

First monoid #

One of the reasons I find universal abstractions beneficial is that you only have to learn them once. As Felienne Hermans writes in The Programmer's Brain our working memory juggles a combination of ephemeral data and knowledge from our long-term memory. The better you can leverage existing knowledge, the easier it is to read code.

Which universal abstraction enables you to choose from a prioritised list of candidates? The First monoid!

In C# with nullable reference types the null-coalescing operator ?? already implements the desired functionality. (If you're using another language or an older version of C#, you can instead use Maybe.)

Once I got that idea I was able to simplify the API.

Parsing and coalescing DTOs #

Instead of that odd Validate method which isn't quite a validator and not quite a parser, this insight suggests to parse, don't validate:

internal Reservation? TryParse() { if (!Guid.TryParse(Id, out var id)) return null; if (!DateTime.TryParse(At, out var d)) return null; if (Email is null) return null; if (Quantity < 1) return null; return new Reservation( id, d, new Email(Email), new Name(Name ?? ""), Quantity); }

This function only returns a parsed Reservation object when the Id is present and well-formed. What about the cases where the Id is absent?

The calling ReservationsController can deal with that:

Reservation? candidate1 = dto.TryParse(); dto.Id = Guid.NewGuid().ToString("N"); Reservation? candidate2 = dto.TryParse(); Reservation? reservation = candidate1 ?? candidate2; if (reservation is null) return new BadRequestResult();

First try to parse the dto, then explicitly overwrite its Id property with a new Guid, and then try to parse it again. Finally, pick the first of these that aren't null, using the null-coalescing ?? operator.

This API also works consistently in the Put method:

dto.Id = id; Reservation? reservation = dto.TryParse(); if (reservation is null) return new BadRequestResult();

Why is this better? I consider it better because the TryParse function should be a familiar abstraction. Once you've seen a couple of those, you know that a well-behaved parser either returns a valid object, or nothing. You don't have to go and read the implementation of TryParse to (correctly) guess that. Thus, encapsulation is maintained.

Where does mutation go? #

The ReservationsController mutates the dto and relies on the impure Guid.NewGuid() method. Why is that okay when it wasn't okay to do this inside of Validate?

This is because the code base follows the functional core, imperative shell architecture. Specifically, Controllers make up the imperative shell, so I consider it appropriate to put impure actions there. After all, they have to go somewhere.

This means that the TryParse function remains pure.

Conclusion #

Sometimes a good API design can elude you for a long time. When that happens, I move on with the best solution I can think of in the moment. As it often happens, though, ad-hoc abstractions leave me unsatisfied, so I'm always happy to improve such code later, if possible.

In this article, you saw an example of an ad-hoc API design that represented the best I could produce at the time. Later, it dawned on me that an implementation based on a universal abstraction would be possible. In this case, the universal abstraction was null coalescing (which is a specialisation of the monoid abstraction).

I like universal abstractions because, once you know them, you can trust that they work in well-understood ways. You don't have to waste time reading implementation code in order to learn whether it's safe to call a method in a particular way.

This saves time when you have to work with the code, because, after all, we spend more time reading code than writing it.

Comments

After the refactor in this article, is the entirety of your Post method (including the part you didn't show in this article) an impureim sandwich?

Not yet. There's a lot of (preliminary) interleaving of impure actions and pure functions remaining in the controller, even after this refactoring.

A future article will tackle that question. One of the reasons I even started writing about monads, functor relationships, etcetera was to establish the foundations for what this requires. If it can be done without monads and traversals I don't know how.

Even though the Post method isn't an impureim sandwich, I still consider the architecture functional core, imperative shell, since I've kept all impure actions in the controllers.

The reason I didn't go all the way to impureim sandwiches with the book's code is didactic. For complex logic, you'll need traversals, monads, sum types, and so on, and none of those things were in scope for the book.

The State pattern and the State monad

The names are the same. Is there a connection? An article for object-oriented programmers.

This article is part of a series of articles about specific design patterns and their category theory counterparts. In this article I compare the State design pattern to the State monad.

Since the design pattern and the monad share the name State you'd think that they might be isomorphic, but it's not quite that easy. I find it more likely that the name is an example of parallel evolution. Monads were discovered by Eugenio Moggi in the early nineties, and Design Patterns is from 1994. That's close enough in time that I find it more likely that whoever came up with the names found them independently. State, after all, is hardly an exotic word.

Thus, it's possible that the choice of the same name is coincidental. If this is true (which is only my conjecture), does the State pattern have anything in common with the State monad? I find that the answer is a tentative yes. The State design pattern describes an open polymorphic stateful computation. That kind of computation can also be described with the State monad.

This article contains a significant amount of code, and it's all quite abstract. It examines the abstract shape of the pattern, so there's little prior intuition on which to build an understanding. While later articles will show more concrete examples, if you want to follow along, you can use the GitHub repository.

Shape #

Design Patterns is a little vague when it comes to representing the essential form of the pattern. What one can deduce from the diagram in the Structure section describing the pattern, you have an abstract State class with a Handle method like this:

public virtual void Handle(Context context) { }

This, however, doesn't capture all scenarios. What if you need to pass more arguments to the method? What if the method returns a result? What if there's more than one method?

Taking into account all those concerns, you might arrive at a more generalised description of the State pattern where an abstract State class might define methods like these:

public abstract Out1 Handle1(Context context, In1 in1); public abstract Out2 Handle2(Context context, In2 in2);

There might be an arbitrary number of Handle methods, from Handle1 to HandleN, each with their own input and return types.

The idea behind the State pattern is that clients don't interact directly with State objects. Instead, they interact with a Context object that delegates operations to a State object, passing itself as an argument:

public Out1 Request1(In1 in1) { return State.Handle1(this, in1); } public Out2 Request2(In2 in2) { return State.Handle2(this, in2); }

Classes that derive from the abstract State may then mutate context.State.

public override Out2 Handle2(Context context, In2 in2) { if (in2 == In2.Epsilon) context.State = new ConcreteStateB(); return Out2.Eta; }

Clients interact with the Context object and aren't aware of this internal machinery:

var actual = ctx.Request2(in2);

With such state mutation going on, is it possible to refactor to a design that uses immutable data and pure functions?

State pair #

When you have a void method that mutates state, you can refactor it to a pure function by leaving the existing state unchanged and instead returning the new state. What do you do, however, when the method in question already returns a value?

This is the case with the generalised HandleN methods, above.

One way to resolve this problem is to introduce a more complex type to return. To avoid too much duplication or boilerplate code, you could make it a generic type:

public sealed class StatePair<T> { public StatePair(T value, State state) { Value = value; State = state; } public T Value { get; } public State State { get; } public override bool Equals(object obj) { return obj is StatePair<T> result && EqualityComparer<T>.Default.Equals(Value, result.Value) && EqualityComparer<State>.Default.Equals(State, result.State); } public override int GetHashCode() { return HashCode.Combine(Value, State); } }

This enables you to change the signatures of the Handle methods:

public abstract StatePair<Out1> Handle1(Context context, In1 in1); public abstract StatePair<Out2> Handle2(Context context, In2 in2);

This refactoring is always possible. Even if the original return type of a method was void, you can use a unit type as a replacement for void. While redundant but consistent, a method could return StatePair<Unit>.

Generic pair #

The above StatePair type is so coupled to a particular State class that it's not reusable. If you had more than one implementation of the State pattern in your code base, you'd have to duplicate that effort. That seems wasteful, so why not make the type generic in the state dimension as well?

public sealed class StatePair<TState, T> { public StatePair(T value, TState state) { Value = value; State = state; } public T Value { get; } public TState State { get; } public override bool Equals(object obj) { return obj is StatePair<TState, T> pair && EqualityComparer<T>.Default.Equals(Value, pair.Value) && EqualityComparer<TState>.Default.Equals(State, pair.State); } public override int GetHashCode() { return HashCode.Combine(Value, State); } }

When you do that then clearly you'd also need to modify the Handle methods accordingly:

public abstract StatePair<State, Out1> Handle1(Context context, In1 in1); public abstract StatePair<State, Out2> Handle2(Context context, In2 in2);

Notice that, as is the case with the State functor, the type declares the type with TState before T, while the constructor takes T before TState. While odd and potentially confusing, I've done this to stay consistent with my previous articles, which again do this to stay consistent with prior art (mainly Haskell).

With StatePair you can make the methods pure.

Pure functions #

Since Handle methods can now return a new state instead of mutating objects, they can be pure functions. Here's an example:

public override StatePair<State, Out2> Handle2(Context context, In2 in2) { if (in2 == In2.Epsilon) return new StatePair<State, Out2>(Out2.Eta, new ConcreteStateB()); return new StatePair<State, Out2>(Out2.Eta, this); }

The same is true for Context:

public StatePair<Context, Out1> Request1(In1 in1) { var pair = State.Handle1(this, in1); return new StatePair<Context, Out1>(pair.Value, new Context(pair.State)); } public StatePair<Context, Out2> Request2(In2 in2) { var pair = State.Handle2(this, in2); return new StatePair<Context, Out2>(pair.Value, new Context(pair.State)); }

Does this begin to look familiar?

Monad #

The StatePair class is nothing but a glorified tuple. Armed with that knowledge, you can introduce a variation of the IState interface I used to introduce the State functor:

public interface IState<TState, T> { StatePair<TState, T> Run(TState state); }

This variation uses the explicit StatePair class as the return type of Run, rather than a more anonymous tuple. These representations are isomorphic. (That might be a good exercise: Write functions that convert from one to the other, and vice versa.)

You can write the usual Select and SelectMany implementations to make IState a functor and monad. Since I have already shown these in previous articles, I'm also going to skip those. (Again, it might be a good exercise to implement them if you're in doubt of how they work.)

You can now, for example, use C# query syntax to run the same computation multiple times:

IState<Context, (Out1 a, Out1 b)> s = from a in in1.Request1() from b in in1.Request1() select (a, b); StatePair<Context, (Out1 a, Out1 b)> t = s.Run(ctx);

This example calls Request1 twice, and collects both return values in a tuple. Running the computation with a Context will produce both a result (the two outputs a and b) as well as the 'current' Context (state).

Request1 is a State-valued extension method on In1:

public static IState<Context, Out1> Request1(this In1 in1) { return from ctx in Get<Context>() let p = ctx.Request1(in1) from _ in Put(p.State) select p.Value; }

Notice the abstraction level in play. This extension method doesn't return a StatePair, but rather an IState computation, defined by using the State monad's Get and Put functions. Since the computation is running with a Context state, the computation can Get a ctx object and call its Request1 method. This method returns a pair p. The computation can then Put the pair's State (here, a Context object) and return the pair's Value.

This stateful computation is composed from the building blocks of the State monad, including query syntax supported by SelectMany, Get, and Put.

This does, however, still feel unsatisfactory. After all, you have to know enough of the details of the State monad to know that ctx.Request1 returns a pair of which you must remember to Put the State. Would it be possible to also express the underlying Handle methods as stateful computations?

StatePair bifunctor #

The StatePair class is isomorphic to a pair (a two-tuple), and we know that a pair gives rise to a bifunctor:

public StatePair<TState1, T1> SelectBoth<TState1, T1>( Func<T, T1> selectValue, Func<TState, TState1> selectState) { return new StatePair<TState1, T1>( selectValue(Value), selectState(State)); }

You can use SelectBoth to implement both Select and SelectState. In the following we're only going to need SelectState:

public StatePair<TState1, T> SelectState<TState1>(Func<TState, TState1> selectState) { return SelectBoth(x => x, selectState); }

This enables us to slightly simplify the Context methods:

public StatePair<Context, Out1> Request1(In1 in1) { return State.Handle1(this, in1).SelectState(s => new Context(s)); } public StatePair<Context, Out2> Request2(In2 in2) { return State.Handle2(this, in2).SelectState(s => new Context(s)); }

Keep in mind that Handle1 returns a StatePair<State, Out1>, Handle2 returns StatePair<State, Out2>, and so on. While Request1 calls Handle1, it must return a StatePair<Context, Out1> rather than a StatePair<State, Out1>. Since StatePair is a bifunctor, the Request1 method can use SelectState to map the State to a Context.

Unfortunately, this doesn't seem to move us much closer to being able to express the underlying functions as stateful computations. It does, however, set up the code so that the next change is a little easier to follow.

State computations #

Is it possible to express the Handle methods on State as IState computations? One option is to write another extension method:

public static IState<State, Out1> Request1S(this In1 in1) { return from s in Get<State>() let ctx = new Context(s) let p = s.Handle1(ctx, in1) from _ in Put(p.State) select p.Value; }

I had to add an S suffix to the name, since it only differs from the above Request1 extension method on its return type, and C# doesn't allow method overloading on return types.

You can add a similar Request2S extension method. It feels like boilerplate code, but enables us to express the Context methods in terms of running stateful computations:

public StatePair<Context, Out1> Request1(In1 in1) { return in1.Request1S().Run(State).SelectState(s => new Context(s)); } public StatePair<Context, Out2> Request2(In2 in2) { return in2.Request2S().Run(State).SelectState(s => new Context(s)); }

This still isn't entirely satisfactory, since the return types of these Request methods are state pairs, and not IState values. The above Request1S function, however, contains a clue about how to proceed. Notice how it can create a Context object from the underlying State, and convert that Context object back to a State object. That's a generalizable idea.

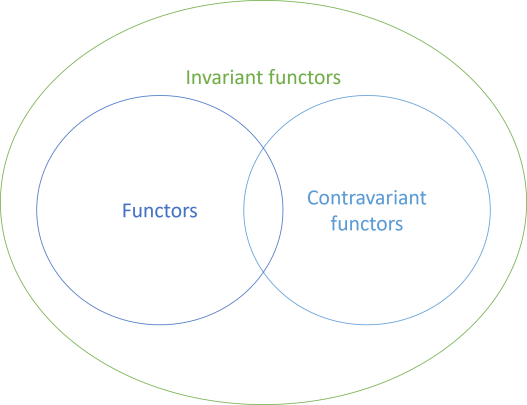

Invariant functor #

While it's possible to map the TState dimension of the state pair, it seems harder to do it on IState<TState, T>. A tuple, after all, is covariant in both dimensions. The State monad, on the other hand, is neither co- nor contravariant in the state dimension. You can deduce this with positional variance analysis (which I've learned from Thinking with Types). In short, this is because TState appears as both input and output in StatePair<TState, T> Run(TState state) - it's neither co- nor contravariant, but rather invariant.

What little option is left us, then, is to make IState an invariant functor in the state dimension:

public static IState<TState1, T> SelectState<TState, TState1, T>( this IState<TState, T> state, Func<TState, TState1> forward, Func<TState1, TState> back) { return from s1 in Get<TState1>() let s = back(s1) let p = state.Run(s) from _ in Put(forward(p.State)) select p.Value; }

Given an IState<TState, T> the SelectState function enables us to turn it into a IState<TState1, T>. This is, however, only possible if you can translate both forward and back between two representations. When we have two such translations, we can produce a new computation that runs in TState1 by first using Get to retrieve a TState1 value from the new environment, translate it back to TState, which enables the expression to Run the state. Then translate the resulting p.State forward and Put it. Finally, return the Value.

As Sandy Maguire explains:

"... an invariant type

Tallows you to map fromatobif and only ifaandbare isomorphic. [...] an isomorphism betweenaandbmeans they're already the same thing to begin with."

This may seem limiting, but is enough in this case. The Context class is only a wrapper of a State object:

public Context(State state) { State = state; } public State State { get; }

If you have a State object, you can create a Context object via the Context constructor. On the other hand, if you have a Context object, you can get the wrapped State object by reading the State property.

The first improvement this offers is simplification of the Request1 extension method:

public static IState<Context, Out1> Request1(this In1 in1) { return in1.Request1S().SelectState(s => new Context(s), ctx => ctx.State); }

Recall that Request1S returns a IState<State, Out1>. Since a two-way translation between State and Context exists, SelectState can translate IState<State, Out1> to IState<Context, Out1>.

The same applies to the equivalent Request2 extension method.

This, again, enables us to rewrite the Context methods:

public StatePair<Context, Out1> Request1(In1 in1) { return in1.Request1().Run(this); } public StatePair<Context, Out2> Request2(In2 in2) { return in2.Request2().Run(this); }

While this may seem like an insignificant change, one result has been gained: This last refactoring pushed the Run call to the right. It's now clear that each expression is a stateful computation, and that the only role that the Request methods play is to Run the computations.

This illustrates that the Request methods can be decomposed into two decoupled steps:

- A stateful computation expression

- Running the expression

Context wrapper class now?

Eliminating the Context #

A reasonable next refactoring might be to remove the context parameter from each of the Handle methods. After all, this parameter is a remnant of the State design pattern. Its original purpose was to enable State implementers to mutate the context by changing its State.

After refactoring to immutable functions, the context parameter no longer needs to be there - for that reason. Do we need it for other reasons? Does it carry other information that a State implementer might need?

In the form that the code now has, it doesn't. Even if it did, we could consider moving that data to the other input parameter: In1, In2, etcetera.

Therefore, it seems sensible to remove the context parameter from the State methods:

public abstract StatePair<State, Out1> Handle1(In1 in1); public abstract StatePair<State, Out2> Handle2(In2 in2);

This also means that a function like Request1S becomes simpler:

public static IState<State, Out1> Request1S(this In1 in1) { return from s in Get<State>() let p = s.Handle1(in1) from _ in Put(p.State) select p.Value; }

Since Context and State are isomorphic, you can rewrite all callers of Context to instead use State, like the above example:

IState<State, (Out1 a, Out1 b)> s = from a in in1.Request1() from b in in1.Request1() select (a, b); var t = s.Run(csa);

Do this consistently, and you can eventually delete the Context class.

Further possible refactorings #

With the Context class gone, you're left with the abstract State class and its implementers:

public abstract class State { public abstract StatePair<State, Out1> Handle1(In1 in1); public abstract StatePair<State, Out2> Handle2(In2 in2); }

One further change worth considering might be to change the abstract base class to an interface.

In this article, I've considered the general case where the State class supports an arbitrary number of independent state transitions, symbolised by the methods Handle1 and Handle2. With an arbitrary number of such state transitions, you would have additional methods up to HandleN for N independent state transitions.

At the other extreme, you may have just a single polymorphic state transition function. My intuition tells me that that's more likely to be the case than one would think at first.

Relationship between pattern and monad #

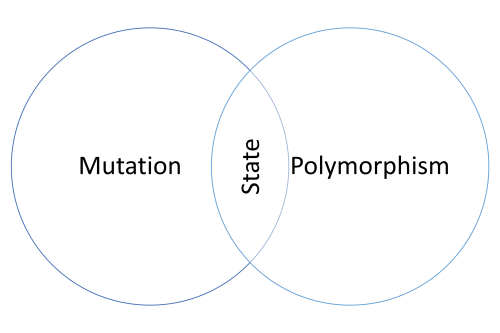

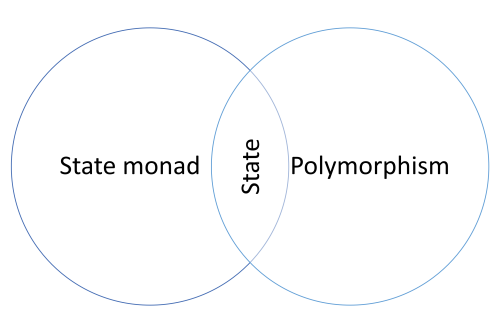

You can view the State design pattern as a combination of two common practices in object-oriented programming: Mutation and polymorphism.

The patterns in Design Patterns rely heavily on mutation of object state. Most other 'good' object-oriented code tends to do likewise.

Proper object-oriented code also makes good use of polymorphism. Again, refer to Design Patterns or a book like Refactoring for copious examples.

I view the State pattern as the intersection of these two common practices. The problem to solve is this:

"Allow an object to alter its behavior when its internal state changes."

The State pattern achieves that goal by having an inner polymorphic object (State) wrapped by an container object (Context). The State objects can mutate the Context, which enables them to replace themselves with other states.

While functional programming also has notions of polymorphism, a pure function can't mutate state. Instead, a pure function must return a new state, leaving the old state unmodified. If there's nothing else to return, you can model such state-changing behaviour as an endomorphism. The article From State tennis to endomorphism gives a quite literal example of that.

Sometimes, however, an object-oriented method does more than one thing: It both mutates state and returns a value. (This, by the way, violates the Command Query Separation principle.) The State monad is the functional way of doing that: Return both the result and the new state.

Essentially, you replace mutation with the State monad.

From a functional perspective, then, we can view the State pattern as the intersection of polymorphism and the State monad.

Examples #

This article is both long and abstract. Some examples might be helpful, so I'll give a few in separate articles:

- Refactoring the TCP State pattern example to pure functions

- Refactoring a saga from the State pattern to the State monad

Conclusion #

You can view the State design pattern as the intersection of polymorphism and mutation. Both are object-oriented staples. The pattern uses polymorphism to model state, and mutation to change from one polymorphic state to another.

In functional programming pure functions can't mutate state. You can often design around that problem, but if all else fails, the State monad offers a general-purpose alternative to both return a value and change object state. Thus, you can view the functional equivalent of the State pattern as the intersection of polymorphism and the State monad.

Next: Refactoring the TCP State pattern example to pure functions.

Natural transformations as invariant functors

An article (also) for object-oriented programmers.

Update 2022-09-04: This article is most likely partially incorrect. What it describes works, but may not be a natural transformation. See the below comment for more details.

This article is part of a series of articles about invariant functors. An invariant functor is a functor that is neither covariant nor contravariant. See the series introduction for more details. The previous article described how you can view an endomorphism as an invariant functor. This article generalises that result.

Endomorphism as a natural transformation #

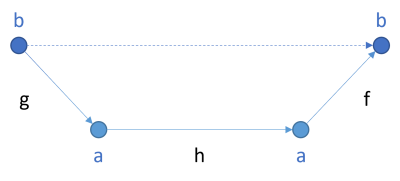

An endomorphism is a function whose domain and codomain is the same. In C# you'd denote the type as Func<T, T>, in F# as 'a -> 'a, and in Haskell as a -> a. T, 'a, and a all symbolise generic types - the notation is just different, depending on the language.

A 'naked' value is isomorphic to the Identity functor. You can wrap a value of the type a in Identity a, and if you have an Identity a, you can extract the a value.

An endomorphism is thus isomorphic to a function from Identity to Identity. In C#, you might denote that as Func<Identity<T>, Identity<T>>, and in Haskell as Identity a -> Identity a.

In fact, you can lift any function to an Identity-valued function:

Prelude Data.Functor.Identity> :t \f -> Identity . f . runIdentity \f -> Identity . f . runIdentity :: (b -> a) -> Identity b -> Identity a

While this is a general result that allows a and b to differ, when a ~ b this describes an endomorphism.

Since Identity is a functor, a function Identity a -> Identity a is a natural transformation.

The identity function (id in F# and Haskell; x => x in C#) is the only one possible entirely general endomorphism. You can use the natural-transformation package to make it explicit that this is a natural transformation:

idNT :: Identity :~> Identity idNT = NT $ Identity . id . runIdentity

The point, so far, is that you can view an endomorphism as a natural transformation.

Since an endomorphism forms an invariant functor, this suggests a promising line of inquiry.

Natural transformations as invariant functors #

Are all natural transformations invariant functors?

Yes, they are. In Haskell, you can implement it like this:

instance (Functor f, Functor g) => Invariant (NT f g) where invmap f g (NT h) = NT $ fmap f . h . fmap g

Here, I chose to define NT from scratch, rather than relying on the natural-transformation package.

newtype NT f g a = NT { unNT :: f a -> g a }

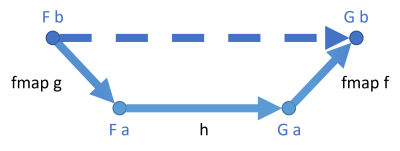

Notice how the implementation (fmap f . h . fmap g) looks like a generalisation of the endomorphism implementation of invmap (f . h . g). Instead of pre-composing with g, the generalisation pre-composes with fmap g, and instead of post-composing with f, it post-composes with fmap f.

Using the same kind of diagram as in the previous article, this composition now looks like this:

I've used thicker arrows to indicate that each one potentially involves 'more work'. Each is a mapping from a functor to a functor. For the List functor, for example, the arrow implies zero to many values being mapped. Thus, 'more data' moves 'through' each arrow, and for that reason I thought it made sense to depict them as being thicker. This 'more data' view is not always correct. For example, for the Maybe functor, the amount of data transported though each arrow is zero or one, which rather suggests a thinner arrow. For something like the State functor or the Reader functor, there's really no data in the strictest sense moving through the arrows, but rather functions (which are also, however, a kind of data). Thus, don't take this metaphor of the thicker arrows literally. I did, however, wish to highlight that there's something 'more' going on.

The diagram shows a natural transformation h from some functor F to another functor G. It transports objects of the type a. If a and b are isomorphic, you can map that natural transformation to one that transports objects of the type b.

Compared to endomorphisms, where you need to, say, map b to a, you now need to map F b to F a. If g maps b to a, then fmap g maps F b to F a. The same line of argument applies to fmap f.

In C# you can implement the same behaviour as follows. Assume that you have a natural transformation H from the functor F to the functor G:

public Func<F<A>, G<A>> H { get; }

You can now implement a non-standard Select overload (as described in the introductory article) that maps a natural transformation FToG<A> to a natural transformation FToG<B>:

public FToG<B> Select<B>(Func<A, B> aToB, Func<B, A> bToA) { return new FToG<B>(fb => H(fb.Select(bToA)).Select(aToB)); }

The implementation looks more imperative than in Haskell, but the idea is the same. First it uses Select on F in order to translate fb (of the type F<B>) to an F<A>. It then uses H to transform the F<A> to an G<A>. Finally, now that it has a G<A>, it can use Select on that functor to map to a G<B>.

Note that there's two different functors (F and G) in play, so the two Select methods are different. This is also true in the Haskell code. fmap g need not be the same as fmap f.

Identity law #

As in the previous article, I'll set out to prove the two laws for invariant functors, starting with the identity law. Again, I'll use equational reasoning with the notation that Bartosz Milewski uses. Here's the proof that the invmap instance obeys the identity law:

invmap id id (NT h)

= { definition of invmap }

NT $ fmap id . h . fmap id

= { first functor law }

NT $ id . h . id

= { eta expansion }

NT $ (\x -> (id . h . id) x)

= { definition of (.) }

NT $ (\x -> id(h(id(x))))

= { defintion of id }

NT $ (\x -> h(x))

= { eta reduction }

NT h

= { definition of id }

id (NT h)

I'll leave it here without further comment. The Haskell type system is so expressive and abstract that it makes little sense to try to translate these findings to C# or F# in the abstract. Instead, you'll see some more concrete examples later.

Composition law #

As with the identity law, I'll offer a proof for the composition law for the Haskell instance:

invmap f2 f2' $ invmap f1 f1' (NT h)

= { definition of invmap }

invmap f2 f2' $ NT $ fmap f1 . h . fmap f1'

= { defintion of ($) }

invmap f2 f2' (NT (fmap f1 . h . fmap f1'))

= { definition of invmap }

NT $ fmap f2 . (fmap f1 . h . fmap f1') . fmap f2'

= { associativity of composition (.) }

NT $ (fmap f2 . fmap f1) . h . (fmap f1' . fmap f2')

= { second functor law }

NT $ fmap (f2 . f1) . h . fmap (f1' . f2')

= { definition of invmap }

invmap (f2 . f1) (f1' . f2') (NT h)

Unless I've made a mistake, these two proofs should demonstrate that all natural transformations can be turned into an invariant functor - in Haskell, at least, but I'll conjecture that that result carries over to other languages like F# and C# as long as one stays within the confines of pure functions.

The State functor as a natural transformation #

I'll be honest and admit that my motivation for embarking on this exegesis was because I'd come to the realisation that you can think about the State functor as a natural transformation. Recall that State is usually defined like this:

newtype State s a = State { runState :: s -> (a, s) }

You can easily establish that this definition of State is isomorphic with a natural transformation from the Identity functor to the tuple functor:

stateToNT :: State s a -> NT Identity ((,) a) s stateToNT (State h) = NT $ h . runIdentity ntToState :: NT Identity ((,) a) s -> State s a ntToState (NT h) = State $ h . Identity

Notice that this is a natural transformation in s - not in a.

Since I've already established that natural transformations form invariant functors, this also applies to the State monad.

State mapping #

My point with all of this isn't really to insist that anyone makes actual use of all this machinery, but rather that this line of reasoning helps to identify a capability. We now know that it's possible to translate a State s a value to a State t a value if s is isomorphic to t.

As an example, imagine that you have some State-valued function that attempts to find the maximum value based on various criteria. Such a pickMax function may have the type State (Max Integer) String where the state type (Max Integer) is used to keep track of the maximum value found while examining candidates.

You could conceivably turn such a function around to instead look for the minimum by mapping the state to a Min value instead:

pickMin :: State (Min Integer) String pickMin = ntToState $ invmap (Min . getMax) (Max . getMin) $ stateToNT pickMax

You can use getMax to extract the underlying Integer from the Max Integer and then Min to turn it into a Min Integer value, and vice versa. Max Integer and Min Integer are isomorphic.

In C#, you can implement a similar method. The code shown here extends the code shown in The State functor. I chose to call the method SelectState so as to not make things too confusing. The State functor already comes with a Select method that maps T to T1 - that's the 'normal', covariant functor implementation. The new method is the invariant functor implementation that maps the state S to S1:

public static IState<S1, T> SelectState<T, S, S1>( this IState<S, T> state, Func<S, S1> sToS1, Func<S1, S> s1ToS) { return new InvariantStateMapper<T, S, S1>(state, sToS1, s1ToS); } private class InvariantStateMapper<T, S, S1> : IState<S1, T> { private readonly IState<S, T> state; private readonly Func<S, S1> sToS1; private readonly Func<S1, S> s1ToS; public InvariantStateMapper( IState<S, T> state, Func<S, S1> sToS1, Func<S1, S> s1ToS) { this.state = state; this.sToS1 = sToS1; this.s1ToS = s1ToS; } public Tuple<T, S1> Run(S1 s1) { return state.Run(s1ToS(s1)).Select(sToS1); } }

As usual when working in C# with interfaces instead of higher-order functions, there's some ceremony to be expected. The only interesting line of code is the Run implementation.

It starts by calling s1ToS in order to translate the s1 parameter into an S value. This enables it to call Run on state. The result is a tuple with the type Tuple<T, S>. It's necessary to translate the S to S1 with sToS1. You could do that by extracting the value from the tuple, mapping it, and returning a new tuple. Since a tuple gives rise to a functor (two, actually) I instead used the Select method I'd already defined on it.

Notice how similar the implementation is to the implementation of the endomorphism invariant functor. The only difference is that when translating back from S to S1, this happens inside a Select mapping. This is as predicted by the general implementation of invariant functors for natural transformations.

In a future article, you'll see an example of SelectState in action.

Other natural transformations #

As the natural transformations article outlines, there are infinitely many natural transformations. Each one gives rise to an invariant functor.

It might be a good exercise to try to implement a few of them as invariant functors. If you want to do it in C#, you could, for example, start with the safe head natural transformation.

If you want to stick to interfaces, you could define one like this:

public interface ISafeHead<T> { Maybe<T> TryFirst(IEnumerable<T> ts); }

The exercise is now to define and implement a method like this:

public static ISafeHead<T1> Select<T, T1>( this ISafeHead<T> source, Func<T, T1> tToT1, Func<T1, T> t1ToT) { // Implementation goes here... }

The implementation, once you get the handle of it, is entirely automatable. After all, in Haskell it's possible to do it once and for all, as shown above.

Conclusion #

A natural transformation forms an invariant functor. This may not be the most exciting result ever, because invariant functors are limited in use. They only work when translating between types that are already isomorphic. Still, I did find a use for this result when I was working with the relationship between the State design pattern and the State monad.

Comments

Due to feedback that I've received, I have to face evidence that this article may be partially incorrect. While I've added that proviso at the top of the article, I've decided to use a comment to expand on the issue.

On Twitter, the user @Savlambda (borar) argued that my newtype isn't a natural transformation:

"The newtype 'NT' in the article is not a natural transformation though. Quantification over 'a' is at the "wrong place": it is not allowed for a client module to instantiate the container element type of a natural transformation."

While I engaged with the tweet, I have to admit that it took me a while to understand the core of the criticism. Of course I'm not happy about being wrong, but initially I genuinely didn't understand what was the problem. On the other hand, it's not the first time @Savlambda has provided valuable insights, so I knew it'd behove me to pay attention.

After a few tweets back and forth, @Savlambda finally supplied a counter-argument that I understood.

"This is not being overly pedantic. Here is one practical implication:"

The practical implication shown in the tweet is a screen shot (in order to get around Twitter's character limitation), but I'll reproduce it as code here in order to not show images of code.

type (~>) f g = forall a. f a -> g a -- Use the natural transformation twice, for different types convertLists :: ([] ~> g) -> (g Int, g Bool) convertLists nt = (nt [1,2], nt [True]) newtype NT f g a = NT (f a -> g a) -- Does not type check, does not work; not a natural transformation convertLists2 :: NT [] g a -> (g Int, g Bool) convertLists2 (NT f) = (f [1,2], f [True])

I've moved the code comments to prevent horizontal scrolling, but otherwise tried to stay faithful to @Savlambda's screen shot.

This was the example that finally hit the nail on the head for me. A natural transformation is a mapping from one functor (f) to another functor (g). I knew that already, but hadn't realised the implications. In Haskell (and other languages with parametric polymorphism) a Functor is defined for all a.

A natural transformation is a higher level of abstraction, mapping one functor to another. That mapping must be defined for all a, and it must be reusable. The second example provided by @Savlambda demonstrates that the function wrapped by NT isn't reusable for different contained types.

If you try to compile that example, GHC emits this compiler error:

* Couldn't match type `a' with `Int'

`a' is a rigid type variable bound by

the type signature for:

convertLists2 :: forall (g :: * -> *) a.

NT [] g a -> (g Int, g Bool)

Expected type: g Int

Actual type: g a

* In the expression: f [1, 2]

In the expression: (f [1, 2], f [True])

In an equation for `convertLists2':

convertLists2 (NT f) = (f [1, 2], f [True])

Even though it's never fun to be proven wrong, I want to thank @Savlambda for educating me. One reason I write blog posts like this one is that writing is a way to learn. By writing about topics like these, I educate myself. Occasionally, it turns out that I make a mistake, and this isn't the first time that's happened. I also wish to apologise if this article has now left any readers more confused.

A remaining question is what practical implications this has? Only rarely do you need a programming construct like convertLists2. On the other hand, had I wanted a function with the type NT [] g Int -> (g Int, g Int), it would have type-checked just fine.

I'm not claiming that this is generally useful either, but I actually wrote this article because I did have use for the result that NT (whatever it is) is an invariant functor. As far as I can tell, that result still holds.

I could be wrong about that, too. If you think so, please leave a comment.

Can types replace validation?

With some examples in C#.

In a comment to my article on ASP.NET validation revisited Maurice Johnson asks:

"I was just wondering, is it possible to use the type system to do the validation instead ?

"What I mean is, for example, to make all the ReservationDto's field a type with validation in the constructor (like a class name, a class email, and so on). Normally, when the framework will build ReservationDto, it will try to construct the fields using the type constructor, and if there is an explicit error thrown during the construction, the framework will send us back the error with the provided message.

"Plus, I think types like "email", "name" and "at" are reusable. And I feel like we have more possibilities for validation with that way of doing than with the validation attributes.

"What do you think ?"

I started writing a response below the question, but it grew and grew so I decided to turn it into a separate article. I think the question is of general interest.

The halting problem #

I'm all in favour of using the type system for encapsulation, but there are limits to what it can do. We know this because it follows from the halting problem.

I'm basing my understanding of the halting problem on my reading of The Annotated Turing. In short, given an arbitrary computer program in a Turing-complete language, there's no general algorithm that will determine whether or not the program will finish running.

A compiler that performs type-checking is a program, but typical type systems aren't Turing-complete. It's possible to write type checkers that always finish, because the 'programming language' they are running on - the type system - isn't Turing-complete.

Normal type systems (like C#'s) aren't Turing-complete. You expect the C# compiler to always arrive at a result (either compiled code or error) in finite time. As a counter-example, consider Haskell's type system. By default it, too, isn't Turing-complete, but with sufficient language extensions, you can make it Turing-complete. Here's a fun example: Typing the technical interview by Kyle Kingsbury (Aphyr). When you make the type system Turing-complete, however, termination is no longer guaranteed. A program may now compile forever or, practically, until it times out or runs out of memory. That's what happened to me when I tried to compile Kyle Kingsbury's code example.

How is this relevant?

This matters because understanding that a normal type system is not Turing-complete means that there are truths it can't express. Thus, we shouldn't be surprised if we run into rules or policies that we can't express with the type system we're given. What exactly is inexpressible depends on the type system. There are policies you can express in Haskell that are impossible to express in C#, and so on. Let's stick with C#, though. Here are some examples of rules that are practically inexpressible:

- An integer must be positive.

- A string must be at most 100 characters long.

- A maximum value must be greater than a minimum value.

- A value must be a valid email address.

Hillel Wayne provides more compelling examples in the article Making Illegal States Unrepresentable.

Encapsulation #

Depending on how many times you've been around the block, you may find the above list naive. You may, for example, say that it's possible to express that an integer is positive like this:

public struct NaturalNumber : IEquatable<NaturalNumber> { private readonly int i; public NaturalNumber(int candidate) { if (candidate < 1) throw new ArgumentOutOfRangeException( nameof(candidate), $"The value must be a positive (non-zero) number, but was: {candidate}."); this.i = candidate; } // Various other members follow...

I like introducing wrapper types like this. To the inexperienced developer this may seem redundant, but using a wrapper like this has several advantages. For one, it makes preconditions explicit. Consider a constructor like this:

public Reservation( Guid id, DateTime at, Email email, Name name, NaturalNumber quantity)

What are the preconditions that you, as a client developer, has to fulfil before you can create a valid Reservation object? First, you must supply five arguments: id, at, email, name, and quantity. There is, however, more information than that.

Consider, as an alternative, a constructor like this:

public Reservation( Guid id, DateTime at, Email email, Name name, int quantity)

This constructor requires you to supply the same five arguments. There is, however, less explicit information available. If that was the only available constructor, you might be wondering: Can I pass zero as quantity? Can I pass -1?

When the only constructor available is the first of these two alternatives, you already have the answer: No, the quantity must be a natural number.

Another advantage of creating wrapper types like NaturalNumber is that you centralise run-time checks in one place. Instead of sprinkling defensive code all over the code base, you have it in one place. Any code that receives a NaturalNumber object knows that the check has already been performed.

There's a word for this: Encapsulation.

You gather a coherent set of invariants and collect it in a single type, making sure that the type always guarantees its invariants. Note that this is an important design technique in functional programming too. While you may not have to worry about state mutation preserving invariants, it's still important to guarantee that all values of a type are valid.

Predicative and constructive data #

It's debatable whether the above NaturalNumber class really uses the type system to model what constitutes valid data. Since it relies on a run-time predicate, it falls in the category of types Hillel Wayne calls predicative. Such types are easy to create and compose well, but on the other hand fail to take full advantage of the type system.

It's often worthwhile considering if a constructive design is possible and practical. In other words, is it possible to make illegal states unrepresentable (MISU)?

What's wrong with NaturalNumber? Doesn't it do that? No, it doesn't, because this compiles:

new NaturalNumber(-1)

Surely it will fail at run time, but it compiles. Thus, it's representable.

The compiler gives you feedback faster than tests. Considering MISU is worthwhile.

Can we model natural numbers in a constructive way? Yes, with Peano numbers. This is even possible in C#, but I wouldn't consider it practical. On the other hand, while it's possible to represent any natural number, there is no way to express -1 as a Peano number.

As Hillel Wayne describes, constructive data types are much harder and requires a considerable measure of creativity. Often, a constructive model can seem impossible until you get a good idea.

"a list can only be of even length. Most languages will not be able to express such a thing in a reasonable way in the data type."

Such a requirement may look difficult until inspiration hits. Then one day you may realise that it'd be as simple as a list of pairs (two-tuples). In Haskell, it could be as simple as this:

newtype EvenList a = EvenList [(a,a)] deriving (Eq, Show)

With such a constructive data model, lists of uneven length are unrepresentable. This is a simple example of the kind of creative thinking you may need to engage in with constructive data modelling.

If you feel the need to object that Haskell isn't 'most languages', then here's the same idea expressed in C#:

public sealed class EvenCollection<T> : IEnumerable<T> { private readonly IEnumerable<Tuple<T, T>> values; public EvenCollection(IEnumerable<Tuple<T, T>> values) { this.values = values; } public IEnumerator<T> GetEnumerator() { foreach (var x in values) { yield return x.Item1; yield return x.Item2; } } IEnumerator IEnumerable.GetEnumerator() { return GetEnumerator(); } }

You can create such a list like this:

var list = new EvenCollection<string>(new[] { Tuple.Create("foo", "bar"), Tuple.Create("baz", "qux") });

On the other hand, this doesn't compile:

var list = new EvenCollection<string>(new[] { Tuple.Create("foo", "bar"), Tuple.Create("baz", "qux", "quux") });

Despite this digression, the point remains: Constructive data modelling may be impossible, unimagined, or impractical.

Often, in languages like C# we resort to predicative data modelling. That's also what I did in the article ASP.NET validation revisited.

Validation as functions #

That was a long rambling detour inspired by a simple question: Is it possible to use types instead of validation?

In order to address that question, it's only proper to explicitly state assumptions and definitions. What's the definition of validation?

I'm not aware of a ubiquitous definition. While I could draw from the Wikipedia article on the topic, at the time of writing it doesn't cite any sources when it sets out to define what it is. So I may as well paraphrase. It seems fair, though, to consider the stem of the word: Valid.

Validation is the process of examining input to determine whether or not it's valid. I consider this a (mostly) self-contained operation: Given the data, is it well-formed and according to specification? If you have to query a database before making a decision, you're not validating the input. In that case, you're applying a business rule. As a rule of thumb I expect validations to be pure functions.

Validation, then, seems to imply a process. Before you execute the process, you don't know if data is valid. After executing the process, you do know.

Data types, whether predicative like NaturalNumber or constructive like EvenCollection<T>, aren't processes or functions. They are results.

Sometimes an algorithm can use a type to infer the validation function. This is common in statically typed languages, from C# over F# to Haskell (which are the languages with which I'm most familiar).

Data Transfer Object as a validation DSL #

In a way you can think of the type system as a domain-specific language (DSL) for defining validation functions. It's not perfectly suited for that task, but often good enough that many developers reach for it.

Consider the ReservationDto class from the ASP.NET validation revisited article where I eventually gave up on it:

public sealed class ReservationDto { public LinkDto[]? Links { get; set; } public Guid? Id { get; set; } [Required, NotNull] public DateTime? At { get; set; } [Required, NotNull] public string? Email { get; set; } public string? Name { get; set; } [NaturalNumber] public int Quantity { get; set; } }

It actually tries to do what Maurice Johnson suggests. Particularly, it defines At as a DateTime? value.

> var json = "{ \"At\": \"2022-10-11T19:30\", \"Email\": \"z@example.com\", \"Quantity\": 1}"; > JsonSerializer.Deserialize<ReservationDto>(json) ReservationDto { At=[11.10.2022 19:30:00], Email="z@example.com", Id=null, Name=null, Quantity=1 }

A JSON deserializer like this one uses run-time reflection to examine the type in question and then maps the incoming data onto an instance. Many XML deserializers work the same way.

What happens if you supply malformed input?

> var json = "{ \"At\": \"foo\", \"Email\": \"z@example.com\", \"Quantity\": 1}"; > JsonSerializer.Deserialize<ReservationDto>(json) System.Text.Json.JsonException:↩ The JSON value could not be converted to System.Nullable`1[System.DateTime].↩ Path: $.At | LineNumber: 0 | BytePositionInLine: 26.↩ [...]

(I've wrapped the result over multiple lines for readability. The ↩ symbol indicates where I've wrapped the text. I've also omitted a stack trace, indicated by [...]. I'll do that repeatedly throughout this article.)

What happens if we try to define ReservationDto.Quantity with NaturalNumber?

> var json = "{ \"At\": \"2022-10-11T19:30\", \"Email\": \"z@example.com\", \"Quantity\": 1}";